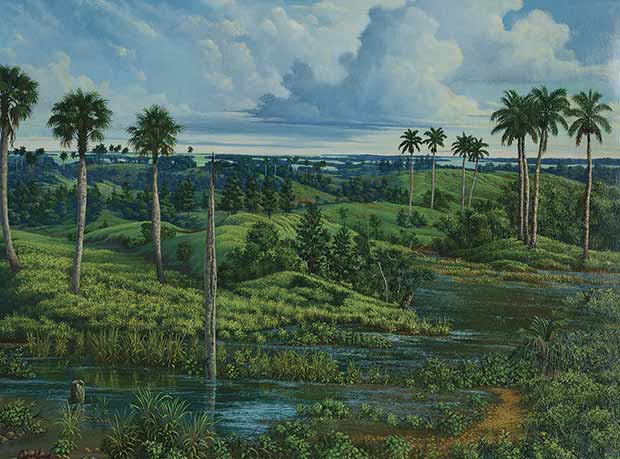

Carlos Manuel has always lived amid the beauty of La Palma, a little town near the mountains in Pinar del Río, a spot on the Cuban map, nestled between Bahía Honda and the Valley of Viñales. Perhaps it was that experience that caused him to look around him, from a very early age, with a piercing gaze. In fact, that background has influenced him so much that while he has tried his hand at other forms of art, landscapes come to him almost genetically, determinately.

“Like a country boy at heart,” he loves Havana, but needs to know that he inhale and breathe deeply; in back of him stand the ancient limestone formations known as mogotes, and in front of him, just a few kilometers away, is the sea—where he can swim as much as he likes with no fear of pollution.

He dreams that someday the local Community Cultural Center, where he took his first steps as an artist, will be revitalized: “La Palma has a lot of talent, and a large group of young people with a predilection for painting. Those young people need to be able to learn, channel their interests, and express themselves.”

Like other landscape artists, during the work process he uses photography “to capture the moment”; however, he says, he does not copy reality such as it is. Instead, he adds elements here and there and changes colors with the purpose of reinforcing feelings and emotions: “The sky might be very clear and blue, but the piece requires a gray sky—rougher and more tempestuous—so I completely intentionally change the intensity of the colors or add a mountain or a palm tree to convey a feeling. Everything depends on what I want to focus on at a given moment.”

Human beings are included—and play a leading role—in Carlos Manuel’s landscape work because, he says: “It is another way of giving expression to spirituality.” When he paints the countryside, he almost always depicts human beings working the land or tending to animals, but now he has been inspired to do a series with special characteristics: “I’m stopping to depict people who go on visits to the countryside. Country people don’t usually receive their visitors in the living room; they usually welcome you in their bohío (thatch-roofed open-air area), which is generally in the back yard, where the kitchen is. Everybody sits down there on taburetes (traditional cowhide chairs) to chat, leaning back against the posts, drinking coffee or eating, with their plates in their hand or on the table. For me, that is a fascinating scene, and it is the one that I would like to preserve.”

He says he feels very comfortable painting in large format because it allows him to concentrate more on the details, something that characterizes his work: “A bird fluttering around in the corner of a painting can be developed subsequently, as another idea. Large format gives me more possibilities for expression, and I think it gives my work cohesion.”

Carlos Manuel has no set schedule; it often happens that he devotes himself so fully to the act of creation that “it might be night or early morning, and I don’t realize that the hours have passed.”

With respect to use of color, he reveals that he does not have any special preferences, but admits that at one time orange, yellow, and red predominated, harmonizing or attenuating a range of blue hues. Now, he says, doing landscapes has obliged him to create his own, mutating language; for example: “In the summer, the mogotes are a thick, intense green that does not provide you with any contrasts or nuances, which is why you have to find variations so that what you’re making is a state of mind, not a true copy. That is my landscape: a state of mind.”

Far from the noise and hustle of the city, Carlos Manuel continues making art in his little corner of Pinar del Río—which can’t be accessed by road, because there isn’t any—and covering canvases with bits and pieces of his life, “which I wouldn’t change for anything in the world.”