PEDRO PABLO OLIVA (Pinar del Río, Cuba, 1949). From 1961 to 1964 he was enrolled at the provincial School of Visual Arts in the western province of Pinar del Río, and subsequently he specialized in painting at the National School of the Arts (ENA) in Havana, graduating in 1970. He is a member of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (UNEAC) and the International Association of Visual Artists (AIAP). He has exhibited in major galleries in Italy, the United States, Panama, Colombia, Spain, Sweden, France, Mexico, and elsewhere. Since 1993, his work has appeared in Christie’s and Sotheby’s Latin American art auctions.

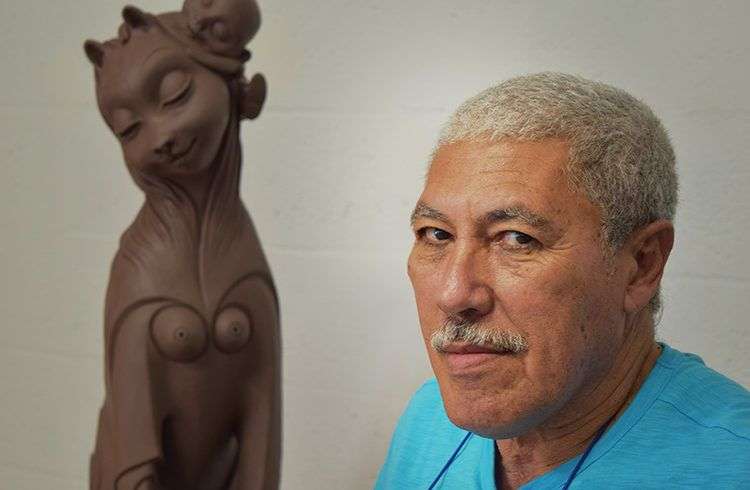

The outstanding visual artist Pedro Pablo Oliva is currently immersed in making seven sculptures that will be conceived at the Fundición R.U.N., in Miami, and that are, in a way, the continuation of a project that he began way back in 1970, when he graduated from Cuba’s National School of the Arts (ENA), where he specialized in painting. Oliva, winner of the 2006 National Visual Arts Award, has moved from two- dimensional to three-dimensional work through ceramics, which is “a way of doing sculpture,” he tells OnCuba in an exclusive interview.

He adds: “I wanted to see my characters sharing the same physical space. I just needed to animate them. Sculpture has the charm of sitting at the table with you; painting

has the wonderful charm of illusion. Without my teachers I wouldn’t have been able to do anything. One was Osmany Betancourt (Lolo), and the other was Miguel Leiva,” he emphasizes. Oliva asserts that his generation—the so-called 70s Generation— “attempted to prolong the journey that previous generations took in search of cubanidad [Cuban-ness].

The goal was to hold onto that term without losing the experience of what was being done outside of that time and context. Nationality is much more than a color, transparency and themes. Above all, it is a spiritual condition that ties you to a cup of coffee or the enchantment of a way of walking, talking and laughing. My generation leaves the same legacy as all generations: utopia.”

On Sept. 7, 1984, at the national Museum of Fine Arts, Pedro Pablo’s first solo exhibition opened: Pinturas, dibujos, bocetos y pasatiempos (Paintings, Drawings, Sketches and Pastimes), and in 2007 he exhibited Historia de amor (Love Story), at the same museum. The two shows are separated by more than 30 years, but they shared the common denominator of his zeal to leave evidence of time experienced: “After three decades, they are separated by another perspective, the one that tells you that you’ve returned to your starting point.

They are united, an absurdity that could only be answered by every human being in this country when they ask themselves, in solitude, what did we do, how did we get here, where did we leave our happiness and love behind; what did they do with our hands and smile; where did we lose the seeds of our dreams. They are united by having said to our eyes: look, this is life,” he says categorically. He admits that his closest influences include Antonia Eiriz and Ángel Acosta León, but the reasons are different.

The first moved him by her “denunciation of hypocrisy, fear of the monster that one carries inside. The mysterious enigma of human relations.” And the second: “The everyday journey to the imagination. Both of them [moved me with] their inner heartbreak.” Convinced that as an artist he has the responsibility of leaving evidence of the era in which it has been his lot to live, Pedro Pablo Oliva believes that painting is another way of talking, of communicating: “My work will be just another testimony to a time lived. It won’t be anything more than a fleeting reference to an era in which reality was much more devastating than any word could be. The utility of a work is infinite or finite.

As the years go by, some vestige of life will emanate from it and somebody will say: “In a place lived a man who expressed his life in his own way, who loved and suffered, who kicked and was kicked, who screamed, and dreamed, but who did not remain silent.” Because of its heavy load of truth, El gran apagón (The Big Blackout, 1994) is considered as the Cuban Guernica; however, according to its artist, every painting is “full of truth and lies, digressions and realities,” and he asserts that he only tried to put himself in everyone’s place: “That painting came out, I don’t know how.

It could never have the expressive anguish of El Guernica, or even its formal impulse.” However, it was unquestionably a cry in response to a crisis; “it was the sense of independence” despite the fact that he believes he could never judge it in all certainty: “I just know that I gave birth to it.” With a beautiful, vast iconography in his possession, Oliva admits that each one of his pieces are like comic strips full of worlds and traps: “Like video games, with the surprise of becoming something else on every canvas, some into a rabbit or a fish, others into a cloud or a stream,” and using color, which he says, “is the trap; after it traps you it talks to you. It is harmony, air. Sometimes I am liberal with it, excessively rational. I have a passion for drawing.”

From the start, this artist’s work has been profound, of pure thought, and bordering deeply philosophical matters, but also clinging to a markedly playful, almost childlike atmosphere: “Creation is as mysterious as man himself. Everything can be a pretext or not. What is certain is that the allusion to childhood appears as a real phantom in my work. Maybe that is why the most serious themes take on a nuance of tenderness that I cannot avoid.”

In response to the question of whether he views life as a permanent battle or a permanent ambush, he clarifies: “Both of them are life. Sometimes they kill you, other times you survive. Sometimes you’re betrayed; others times you are covered with glory. I have loved a lot, and I have been loved. At other times I have loved and not been loved; I have not loved and been loved. Life is a war to achieve a stability that does not come very often. Triumphs are ephemeral, like insects that never see the sun. I painted what I lived, and therefore, I was surprised by the amazement.”