In a conversation with Juanito—as he’s known—one feels that behind every affirmation or word he speaks, a conceptual discourse is born, or better said, forged, after years of struggle among artists, fundamentally in the visual arts. The 20 years he worked as a representative for the maestro Manuel Mendive have been very useful.

Juan Delgado Calzadilla was born in Havana, and earned a economics degree in 1989: “One is born with the interest and then live leads you to the most beautiful thing,” he says in a conversation with OnCuba, while not attempting to hid his very humble origins or the fact that he never once saw a work of art in his home during in his childhood, which he spent in the densely populated working-class neighborhood of Arroyo Naranjo. “My father, a factory worker, was a fantastic person, and he taught me, as did my mother, that the most beautiful thing in live is to be honest and hard-working. I grew up hearing the proverb, “Do good to all alike.”

Juanito is a innate promoter, and in many ways, a creator who has a real nose and a sharp eye for finding good art, and knowing how to look for and find the channels for promoting it. “Even though I have worked long and hard, I feel that I have been very fortunate; for years, I’ve been in a dialogue with and traveling from Cuba to the United States, trying to make Cuban art known and to establish an open dialogue with all artists, wherever they are. I’m very happy to have the ability to understand people, and I haven’t been alone in that, because many others have worked for the same,” he emphasizes with a smile.

His high school years were spent at the rigorous Vladimir Ilich Lenin school, and when he finished he opted for a scholarship to study Art History in the former Soviet Union. “The scholarship never came and my teacher, Caridad Martínez, who knew I was good at math, suggested that I study economics. When I went to the Faculty of Economics, I came across a fabulous mural by the painter Mariano Rodríguez, and that coexistence of four years marked me. Since then, I have been an art enthusiast.”

In 1982, he began working for the Cuban Fund for Cultural Assets (Fondo Cubano de Bienes Culturales, FCBC). “There I met Nisia Agüero, a great woman, whose name will have to appear when the recent history of Cuban culture is recorded. Nisia realized that economics held absolutely no interest for me, and put me to work with her. I learned a lot, especially by listening, something that I recommend to young people; first you have to learn how to hear, you have to learn how to think for yourself, and then you can dialogue or argue,” he says emphatically.

Thanks to his work at the Fund, he met René Portocarrero, Martínez Pedro, Sandú Darié, Mariano Rodríguez, and all the great masters of that time, and he quickly understood—thanks to Nisia’s vision—the importance of linking together all expressions of the arts. “With her, I did my first international tour of the then-socialist countries, and then I went to Greece, where I organized a Cuban culture week.”

He met Mendive and they became friends. In 1984, during the first Havana Biennial, they awarded the maestro the important Espacio Latinoamericano Gallery Prize, from París, and as he worked in the Fund’s department of protocol and international relations, he organized Mendive’s trip to France a year later. “For year, I simultaneously worked at the Fund and worked as an assistant to the maestro. In the summer of 1987, he asked if I could help organize a performance that he would do at the National Museum of Fine Arts (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes) based on his first exhibition, Para el ojo que mira (For the Eye that Looks). The truth is that production issues suit me well, and with the impetus of youth, I gave myself over to the task. That was when I began working systematically with Mendive, which was a real school for me. Because I never studied Art History, the most important thing was to learn, and—together with the maestro—I began enjoying and appreciating classical music and loving theater and ballet, which opened up many worlds for me. I remember that when we would travel, he would take me to the museums to see art, and every time he dragged me up to the fourth floor of the Georges Pompidou National Center of Art and Culture to enjoy the permanent collection, he would explain every single work to me, with a plethora of details. It was a privilege, and I really turned into a hard drive, storing up information.”

As an independent curator, this man of culture has been connected with the Havana Biennial from the very start, and emphasizes that he has been able to create “a private working style within the arts” that has brought him excellent results.

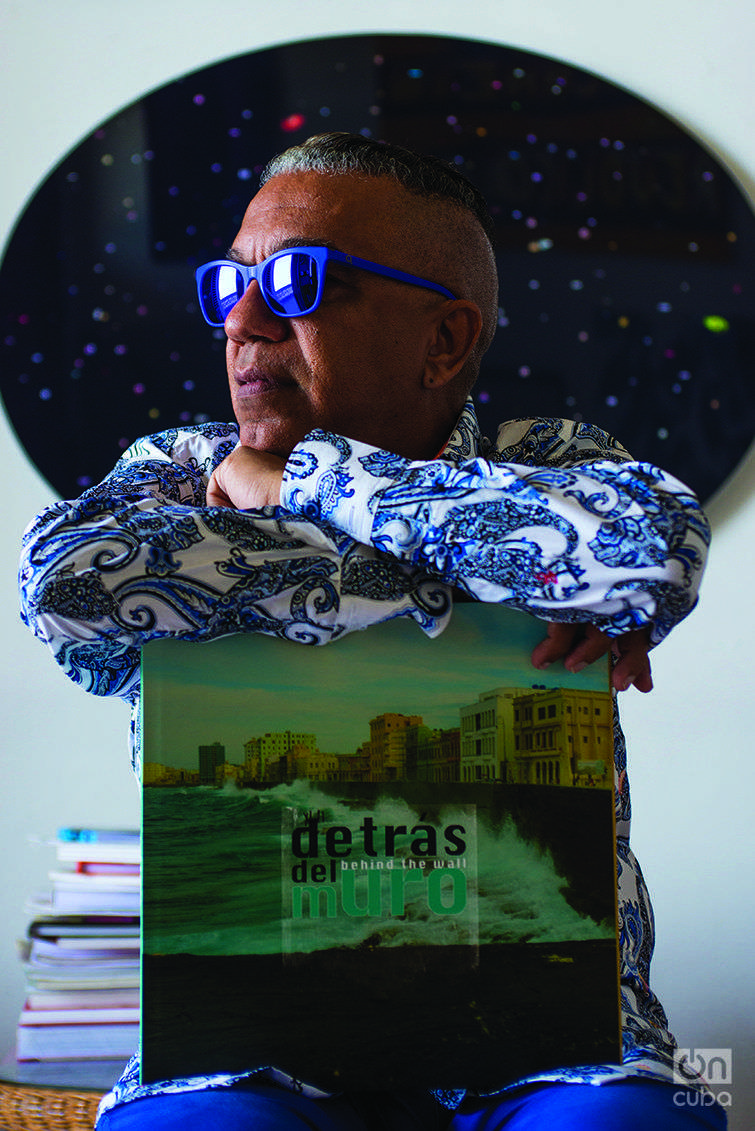

Regarding Detrás del muro (Behind the Wall)—for the first time at the 11th Biennial—he emphasizes, “It was hard for people to understand a project of such magnitude on Havana’s traditional and emblematic Malecón,” and admits that he had to deal with many difficulties and misunderstandings. “I have a whole file full of permits and approvals, and also denials! I think that those are the mental walls that have to be brought down to finally see art for what it is: a direct reflection of society.”

He says that in the first edition of Detrás del muro, he received “intelligent and beautiful” proposals from young people, second-year students at Cuba’s university for the arts, ISA, which pleasantly surprised him, but were not materialized. “Censorship obliges talent and I never keep my mouth shut; if they tell me ‘no,’ I look for the ‘yes.’ Plus, the experience of working as a collective was vital, and I would like to mention my team, which is made up of Elvia Rosa Castro, José Fernández, Indalma Fontirroche, Daniel González and Roberto Torres. As the Yorubas say, ‘A single pole does not a mountain make.”

At the second edition of Detrás del muro—at the 12th Biennial, from this past May to June—the international element was very strong, and the project involved well-known artists from Colombia, Germany, Morocco, United States, Spain, the Dominican Republic, and other countries. “I’ve never been interested in localism, because sometimes that term keeps us from being understood. I like universalization beyond any borders, and if there is talent and conviction it doesn’t matter if one is Cuban or not. The project Detrás del muro stays in the city, and that’s the most important think, that Cubans elevate their spirit through art.”

He announces that he and his team “are now working on the third edition of Detrás del muro,” but in parallel he is immersed in obtaining financing for producing a book that documents the second edition, and at the same time, production is underway on a second documentary, Limbo, directed by the experienced filmmaker Lester Hamlet. “ I really hope that in the future, Detrás del muro will become a beautiful institution or foundation that will help make the city into a giant museum of urban art, because there is an immense thirst around the art market, and I continue to have a passionate thirst for art. We’ve survived all these years, but we have to promote Cuban artists and intellectuals and shatter taboos. I am working for four letters: C-U-B-A.”

Juanito, with his boundless impetuosity and tenacity, is still dreaming big: “I want to inundate all of the floor of New York’s Museum of Modern Art with Cuban art!” And I don’t doubt that he will.