“Cuban society has interested me for more than 30 years, and in fact, I learned photography here.” This is the first thing Canadian photographer Jean-François Bouchard, creator of the series The New Cubans, tells me. The series will be on display for one month, starting Friday, March 28, at the Galería Taller Gorría in Old Havana.

The title of this project directly alludes to youth, but its content is more complex.

Bouchard began working on this series in 2017, but his work halted during the pandemic. Upon the artist’s return to Havana, most of these snapshots, now on display in Cuba, were created. Their first stop was the Blouin Division gallery in Montreal, in an exhibition that ended on November 16.

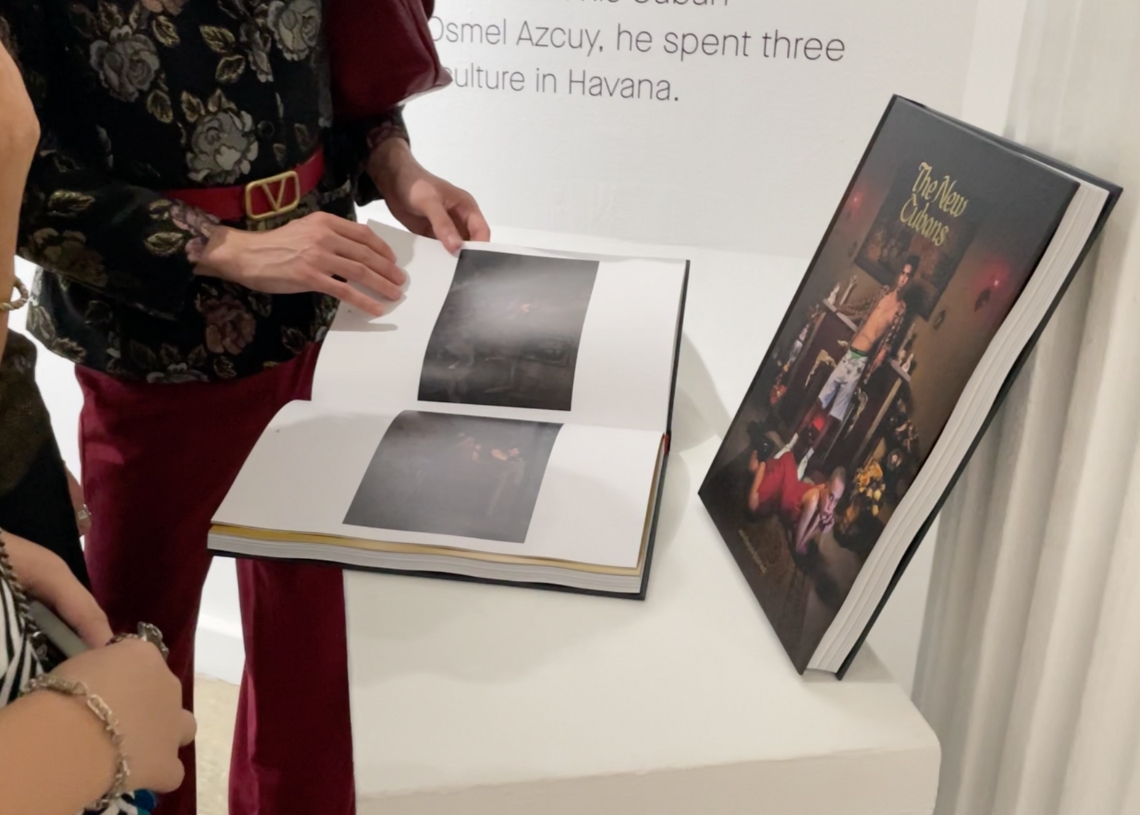

The collection consists of 150 photographs compiled in the book of the same name. Only a selection of them makes it to the exhibition walls.

What do the new Cubans talk about?

After more than three decades of walking, photographing, rediscovering, and witnessing processes and changes on the island, Bouchard began to question the imagery that often prevails in the world of photography regarding Cuba.

“I’ve been interested in Cuba’s past for a long time, but of course I’m interested in the future, and therefore in the younger generation. Where should I start?” Bouchard wondered about the reason for this perspective, halfway between documentary and fiction.

“Foreigners have a certain vision of Cuba, but there’s more, and that’s what I wanted to show them, what most visitors don’t get to see or discover,” he says, while explaining the reasons that led him to delve not only into a specific generation, but into a part of it, one that speaks of nonconformity, irreverence, and a break from the patterns that have historically characterized Cuban society.

According to Jorge Peré, the project’s curator, what Bouchard categorizes as “the new Cubans” is “a new lifestyle, a social spectrum that didn’t previously exist in Cuba, but has flourished due to the vindication of minority identities; a social group that had been somewhat isolated for many decades has become more visible.”

Bouchard didn’t just reach the people who make up the stories in the series. He also featured the essential collaboration of model, photographer, and fashion designer Devon Ruiz, and fellow Cuban photographer and visual artist Osmel Azcuy. The idea was to construct the narrative of each of these images, in which the theatricality of their visuality is constructed, but the lives they reflect and the styles of their subjects are real.

For Beatriz Hernández Jiménez, producer of the exhibition, these images speak about “a sector of young society that has ways of expressing itself intellectually, culturally, and of course, physically, in terms of representation and appearance in society. This is quite distinctive and is also important for understanding the new dynamics of thought, the heterodoxy among youth, and how it projects itself outward.”

It’s impossible to talk about Cuban society without considering the thorns that wound it today: emigration and the economic situation, with their impact on almost everything, and of course on the thinking and ways of seeing and embracing life that young people are building today.

The French historian Marc Bloch once said: “Men are more children of their time than of their parents.”

Clichés aside

An important part of what each of the photographs in The New Cubans has to say is the setting, the elements that make up each scene.

A text on the wall at the entrance to the exhibition announces that we will attend a “visual journey that dismantles the all-too-common clichéd foreign representations of Cuban cigars, vintage cars, all-inclusive resorts, and echoes of the Cold War.”

However, Cubans are not so alien to the objects or visualities that accompany the subjects: ornaments that have been accompanying Cubans for decades in a recurrent way in many homes, religious, patriotic, and political symbols, destruction, the aesthetics of neglect, and poverty.

These ways of speaking make this perhaps a completely disruptive exhibition of typical Cuban discourse outside of Cuba, but on the island, the theatricality of the pieces takes on a completely different dimension.

“Seeing these photos, the public might think that Jean falls squarely into various stereotypes. In reality, what he’s doing is mocking those archetypes. A photographer with his critical insight and photographic expertise wouldn’t fall into the clichés of visuality, nor into the common places typically seen. In fact, what it does is take all those clichés and bring them together in each setting. Each photo becomes a deconstruction of what the archetypal Cubans mean.

“The greatest reality of these photos is that those posing are people living those lives; they weren’t placed there as mannequins or mere decoration. It’s an act of nakedness and honesty before the photographer, and what the photographer does is overload the scene,” explains Jorge Peré.

In these photos, the scenographic montage is perhaps the best way to show the depth of the rupture that these “new Cubans” represent with the rest of society and with the reality in which they were born, raised, and educated, even though they are not the majority.

“My work focuses on acceptance, love, and respect for people who are different. The series is a great celebration of that,” concludes Jean-François Bouchard.