Havana, September 2015. The first thing I saw when the plane landed was his face. Not the immigration officer’s, nor my mother’s, who waited outside, small and sleep-deprived, her eyes red from crying over my father’s sudden death just days before.

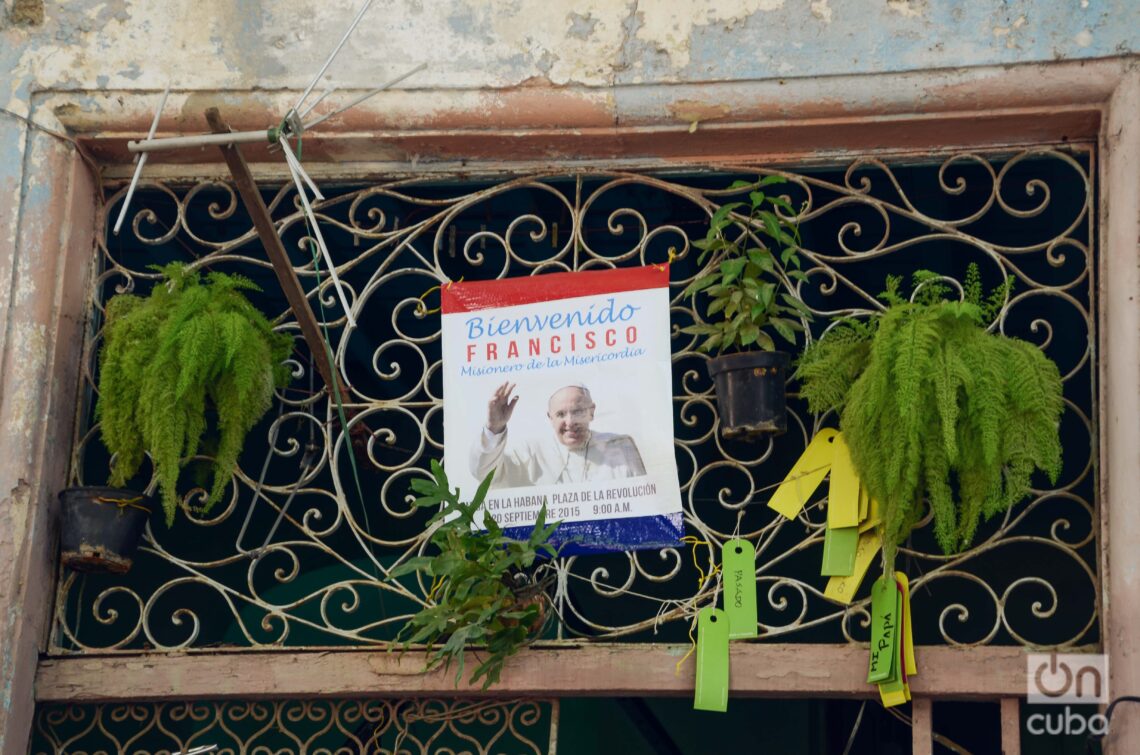

The first face I saw upon arriving in Cuba that afternoon was Pope Francis’. Smiling, with his hand raised in greeting, he gazed at me from a full-color poster hung high in José Martí International Airport. “Missionary of Mercy,” read the text. I didn’t take photos—weighed down by the long hours of travel and the painful family news. But that welcome billboard left no doubt: I had landed during a special moment, in the days leading up to His Holiness’ arrival on the island.

In less than twenty years, three popes had set foot on Cuban soil: John Paul II in 1998, with his unforgettable “May Cuba open to the world and may the world open to Cuba”; Benedict XVI in 2012, with a more measured, less effusive gesture that passed almost without notice; and now Francis: the first Latin American, the first Jesuit, the first to bring not just a spiritual message but a discreet yet powerful diplomacy that had contributed to the thaw between Havana and Washington. Francis was no ordinary pope. Not, at least, for Cuba. Not at that moment.

I crossed practically the entire country, from Havana to Holguín, over a full day, to take my father’s ashes to his homeland and scatter them, as per his last wishes, in the neighborhood where he was born, grew up, and lived much of his life. And like a travel companion, there was Bergoglio, his smile stamped on every town we passed through.

The entire country seemed to have been overtaken by an evangelizing force foreign to its own tradition. Cuba isn’t fervently Catholic like Mexico or Colombia. In my country, faith mixes with Santería, syncretism, and a structural distrust of institutions. But there was something about the Argentine pope’s figure that generated great enthusiasm. And amid it all, a strange graphic fever.

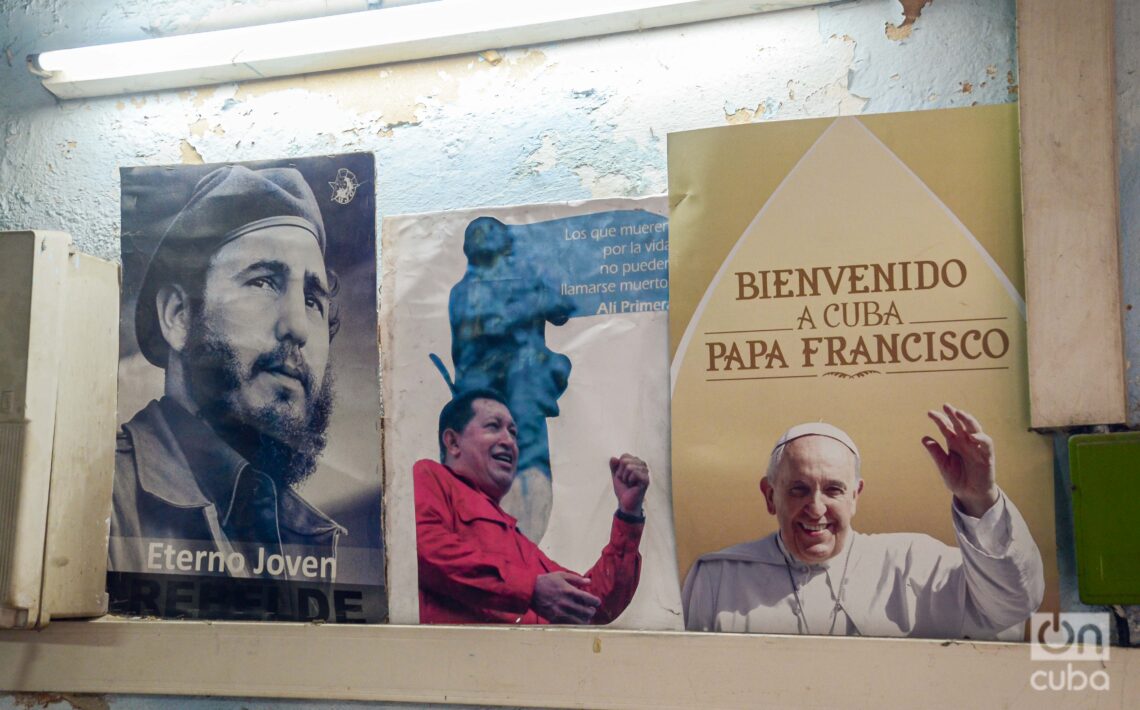

Walking from El Vedado to Centro Habana, through Playa or El Cerro, or in neighborhoods of Holguín, posters with the pope’s face or messages praising his visit were everywhere. Sometimes it was an official giant billboard; others, an improvised sign on a bicitaxi, a poorly printed sticker on an almendrón’s windshield, or the wooden crate of a street vendor selling root vegetables. His face even shared space on CDR murals with Fidel’s. Francis was omnipresent.

The pope’s photo showed a gentle smile, slightly tilted. A gesture that could mean many things: hope for believers; intrigue for skeptics; for many Cubans, simple curiosity. My aunt Vicky, who isn’t Catholic—rather atheist—told me, pointing to the fan with Francis’ face that she used to combat the heat those days: “This man has the face of a good person.”

In Cuba, where anything that breaks the routine is celebrated intensely, the papal visit had become a national event. The Pope fever was widespread. It was visual. It was performative. And it was profoundly Cuban.

On September 19, 2015, when the Alitalia Airbus A330-200 carrying the papal flight finally landed, Havana was in a state of anticipation. Thousands took to the streets: some for faith, others out of curiosity, many simply to be there.

The first Mass, like his predecessor John Paul II had done, was held at Plaza de la Revolución. With the National Theater at his back, the pontiff had the giant silhouette of Che Guevara to his left and, a few meters away, Camilo Cienfuegos’; to his right, the monument to José Martí. A setup that could only happen on this island of magical realism, without anyone questioning this mix of ideologies and creeds too much.

In the Plaza, transformed into a gigantic open-air Mass, one could feel both fervor and bewilderment. The vast majority were faithful from different latitudes. There were people praying, and others yawning (because the event was very early). There were even those who weren’t quite sure why they were there but stayed anyway. “You don’t see a live pope every day. And Cubans, if anything, are curious if not downright nosy,” I remember a young woman telling me jokingly after the liturgy, with no apparent signs of being Catholic.

During his four-day visit to Cuba, the pope wasn’t only in Havana but also celebrated Masses in Holguín and Santiago de Cuba, reaching out to communities in the country’s east with gestures of faith and reconciliation.

If the Masses and official events maintained a ceremonial tone, Cuban streets during those days were something else: a mix of popular revelry and carefully orchestrated spectacle. The same happens in many countries that receive the pope, of course. But in Cuba, this combination had a unique flavor: that Cuban spontaneity, that ability to appropriate the foreign and make it their own, to sanctify and profane simultaneously.

On September 22, when Francis departed for the United States, the country almost abruptly returned to its routine. The posters began disappearing: some torn down, others kept as souvenirs. The streets regained their usual rhythm: lines, buses, reggaeton, heat. But something remained, because in Cuba, even the few non-believers celebrate.

We must never forget that this land, blessed by three popes, is a unique place where the extraordinary—when it happens—is lived as a party, as ritual, as an inevitable chronicle. And during those September days in 2015, what we experienced was a Pope fever.