What are the chances of bumping into the author of a novel within hours of reading its last few pages? What causes and chances must come together for the meeting to happen?

These are the questions that assailed me immediately after saying goodbye to Leonardo Padura and Lucía, his partner, after having met them by chance in the midst of the swarm of people typical of an airport as busy as Tocumen, in Panama.

A few months ago, at the Buenos Aires book fair, I bought Personas decentes, his most recent novel, published by Tusquet in 2022. It was an express request from Havana, from my aunt Vicky, a fervent reader of Padura (one more), who had devoured some fragments of the book via WhatsApp.

“I was hooked; but just imagine, there, on that little screen, it’s a real nuisance. And here I won’t be able to find the book,” she had told me then.

So on the occasion of a new trip to the island I decided to take this and other texts as a gift to my aunt. It isn’t the first time that from Argentina I take Padura’s books to Cuba, despite being a living Cuban author who is also in Cuba.

Once in Havana, I couldn’t put the novel down until the last day of my stay because…I also got hooked on the tenth appearance of detective Mario Conde!

I started reading Personas decentes during the twelve-hour journey between flights and stopovers that takes me from Buenos Aires to Havana. Once in Cuba, I couldn’t stop reading. My aunt would have to wait a little longer.

Havana turned out to be the best setting to immerse myself in the pages of Conde’s saga. There was a special connection to Padura’s narrative as I walked around and observed the city and the people. Every corner seemed to make new sense and sometimes I felt like one more character in the story. One night, perhaps pushed by the plot, I found myself walking through San Isidro, the Havana neighborhood of Yarini, the famous pimp from the beginning of the last century and one of the protagonists of the book.

One of the “Havanas” that the book recreates, the one set in 2016 in the midst of the hustle and bustle of Barack Obama’s visit, the Rolling Stones concert and the exclusive Chanel parade along the Paseo del Prado, was mixed in July 2023 with the crude city through which I walked and photographed under a blazing sun and colossal heat.

Barely a few years have passed between the Havana of the book and today’s, but it seems like a lifetime. Few goods available, imported and at exorbitant prices, totally far away from the pocket of any worker, in the midst of an extreme shortage that hits millions of Cubans hard on a daily basis.

In the midst of desolate streets due to the lack of transportation, the discouraged voice of Mario Conde resounded in my head, or perhaps I identified so much with him that I could be Conde himself, as a photographer instead of a detective, observing our city and its people in a way never experienced before. Conde’s social x-rays in the book and my visions outside of it were just as compelling.

After twenty days in Cuba, the night before returning to Argentina, as if in a race against time, I finished reading the last chapter of Personas decentes. Of course, my aunt, who wouldn’t let me leave the country if I didn’t hand it over to her, was looking forward to it. That’s when I also found out that a family queue had formed for its reading between my mother, my brother and other relatives. In the country of queues, I would be happy to celebrate one.

Less than 24 hours later, I would meet Leonardo Padura himself.

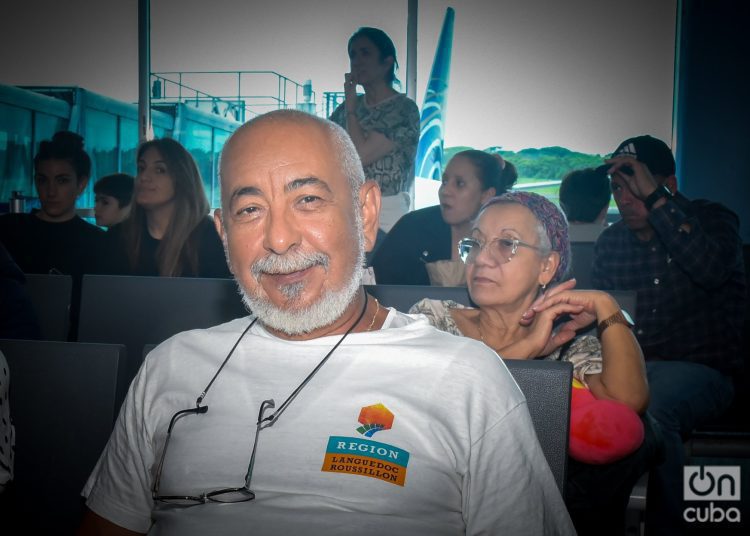

Coming from Havana, on the way to Buenos Aires, I made a short stopover in Panama. While enjoying a coffee at the airport, I was able to recognize the writer among the crowd of passengers. He was moving with a hurried step in a wide corridor of the terminal. He had a carry-on bag with him. He was dressed casually — a white T-shirt and shorts — radiating the relaxed style of someone who lives in an eternal summer.

When he passed a short distance from me, I didn’t hesitate to approach him. I was moved by the emotion of meeting the acclaimed Cuban writer, National Award for Literature and Princess of Asturias Award for Letters, whose latest work had accompanied me on my walks through our common land.

“Maestro, I’m Cuban,” I said hastily, making my way through the crowd. Without even asking if he wanted to say hello to a stranger in the rush, I shook his hand. Perhaps he is already used to similar situations; probably less at an airport about to board a plane.

I realized that I only had seconds, so I felt invaded by the selfie instinct. Giving in to the desire for evidence, the narcissism that encompasses what the Argentines call “cholulaje” took over me.

However, the writer responded with a smile and kindly accepted the photo proposal. “Of course; but come on, my plane is leaving. You already know how that is,” he said sympathetically as he made an effort to appear good in the snapshot as if we were lifelong friends. It was a truly generous gesture.

I realized then that he was accompanied by Lucía, whose name appears in almost all the dedications of his books. Lucía López Coll, renowned philologist, specialist in Cuban literature and screenwriter. Of course, I enlarged the frame of the selfie and the three of us entered the frame, smiling and in harmony.

But it would only be a fleeting first act; minutes later we would have another more leisurely, thoughtful and enjoyable chapter.

I have had the privilege of attending various presentations of his books, both in Cuba and in Argentina. Conversations and talks. However, on those occasions he was always surrounded by dozens of avid readers. This time it was different.

We bumped into each other again in the waiting room. Our departure gates were next to each other. They were headed for Santo Domingo, for the launch of an updated reissue of Los rostros de salsa, Padura’s book that compiles interviews with great exponents of that musical genre. In addition, he was going to give a workshop on journalism and literature for young people.

The free time of this couple must be very scarce. In a way, the brief pause during the stopover at an airport may be a quiet moment that I was afraid to disturb. But I took the risk.

I again launched myself into the meeting, determined to tell him that I was a photographer and that in the past I had had the privilege of visiting his home and taking a picture of him preparing the coffee pot (“I do that four times a day,” he would confess to me later). If he agreed, I would propose his posing for a picture at that very moment, surrounded by the people at the airport, like the great personality of Hispanic letters and pride of Cuban culture that he is. Plus, on the way, I could strike up a conversation about his vast literary oeuvre, from his captivating novels to his insightful journalistic reporting, and of course, discuss his latest book.

Padura willingly agreed to get in front of my camera; as if he didn’t have the word “no” close at hand. Again, with a smile on his face, he posed for the few shots I took. The most significant thing was that, between each click, he started a spontaneous, enjoyable and fluid chat.

In other corners of the planet, if a reader finds an admired writer, he is likely to ask for an autograph and ask questions about characters and stories. This time, the reader, the writer and his wife are Cuban and they are in a foreign airport. It was unavoidable that the first topic of the talk was Cuba; the famous “how are things.”

It was precisely Padura who started the conversation: “How did you see it?”

I immediately thought of a fragment from Personas decentes I had made a note of, because the images described and captures by him in literature had struck me when I saw them while wandering around the city:

“Conde saw a swarm of old people with worn-out shoes and withered eyes, in search of the meager livelihoods achievable with their pensions, increasingly diminished by the stratospheric prices that life was reaching.… The countless inhabitants of the city that had not reached their turn in the queue of dreams. The majority portion in which he himself was a member.”

I confessed to them that year after year when I visit Cuba I notice that daily life becomes more and more complex; and that this time I felt the deterioration much more.

“For us Cubans who live on the island, this deterioration is something we witness day after day and, in a certain way, it does not surprise us,” Padura replied. “But for Cubans like you, who go, say, once a year or more, the impact is much stronger. With each trip, the shock becomes more abrupt,” added the writer.

For almost half an hour we shared concerns and opinions as any group of Cubans does in Cuba and outside of it. Although literature could have been the meeting point, circumstances led us down other paths.

It was a meaningful and comforting encounter in which the weight of distance melted away in the communion of our shared experiences — and our hopes.