A part of the Mukataa complex is frozen in time, specifically in October 2004. It is the bunker in which the then-president of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), Yasser Arafat, installed his offices and residence. It happened during the final days of an Israeli military siege that kept him confined for almost three years in these facilities.

The Mukataa, located in Ramallah, occupied West Bank, was built at the beginning of the last century during the British Mandate and was used as a prison. Today it houses the headquarters of the PNA, the Yasser Arafat Museum and a small mausoleum with the remains of the Palestinian leader built shortly after his death in 2004.

Arafat rests under a tombstone made of Jerusalem stone. His is not an eternal rest, but provisional. His people dream of and hope for the creation of a Palestinian State and the recovery of Jerusalem, occupied by Israel since 1967. When that day comes, the remains of the Palestinian leader must be transferred to the Dome of the Rock, in the Esplanade of the Mosques, the third holiest place in the Islamic world.

The museum is large, very well set up and narrates through audios in various languages the history of the struggles of the Palestinian people to conquer sovereignty.

There are images from the British Mandate, from the Six-Day War, from the first and second Intifadas; historical documents; record of the signing of important agreements such as those of Oslo or the Camp David summit. In addition, objects belonging to Arafat make up the exhibition: his glasses, his iconic kufiya — the typical Palestinian headdress —, his pistol and his olive green uniform.

In many ways, the museum reminds me of those in Cuba. The theme of liberation struggles, the justness of a cause, the veneration of the leader. Even visitors remember our museums! One of the three times I’ve gone I ran into a group of Palestinian children, uniformed and wearing scarves around their necks. They came to the museum with Palestinian flags and photos of Arafat and Abbas, the current president of the PNA. Sounds familiar?

The tour ends with a visit to the basement-turned-bunker where Arafat spent his last days with members of the PNA leadership and his personal escort, before being hospitalized in Clamart, France. The site remains as it was then, or so they tell us. There are sandbags in the windows, gasoline cans, AK rifles lying on the guards’ beds, mattresses on the floor, military uniforms thrown here and there. Chaos reigns, as it must have reigned in those days when a small group of people resisted intense attacks sheltering in a basement.

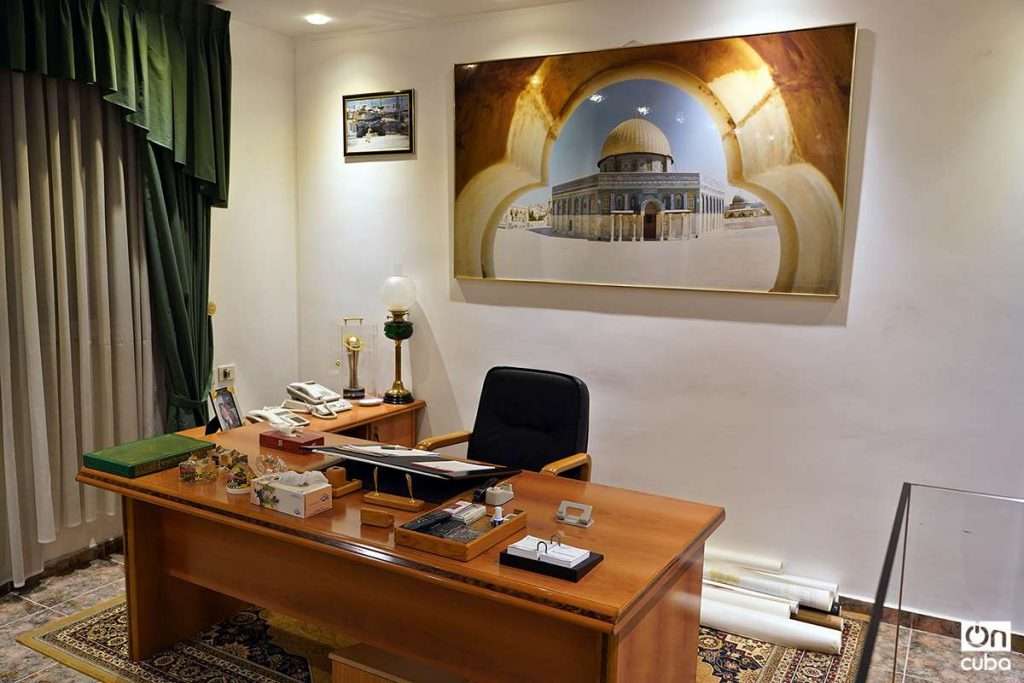

The meeting room with the desk used by Arafat and a photo of the Dome of the Rock in the background has been preserved. The bunker includes a kitchen and a very small room in which the leader slept. His uniforms are still hanging in a closet. There is an old TV set, a stove and an artificial respiration apparatus.

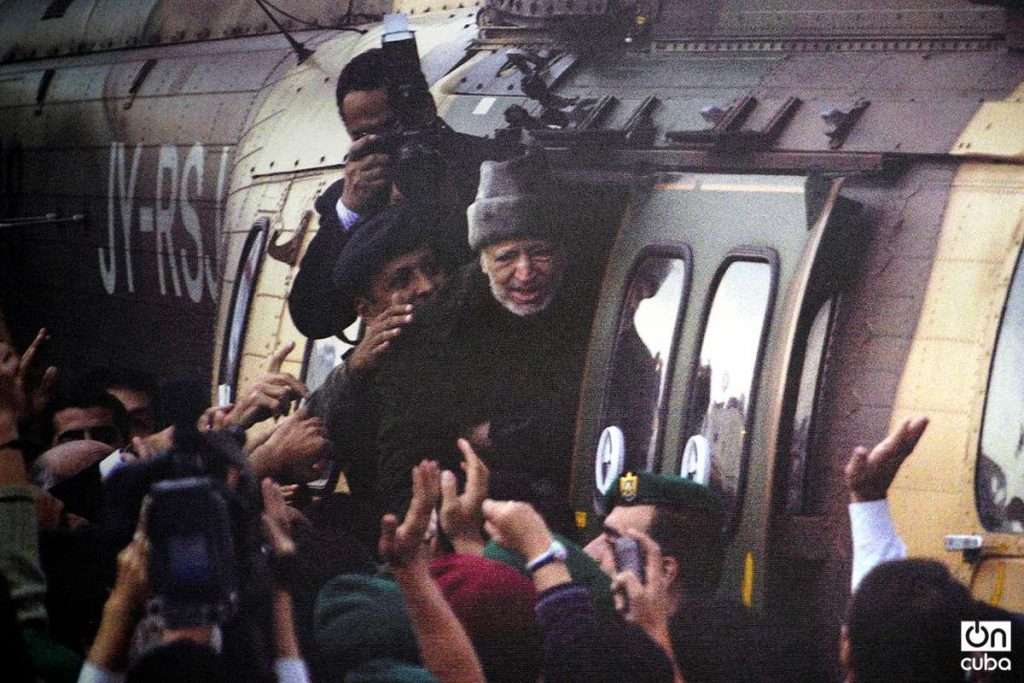

But of the entire complex what strikes me the most is a photo. It is almost at the end, before accessing the bunker. It is a photo that I would have liked to have taken, like so many others that a photographer would like to be the author of. It happens to me with the image of an old and sick Arafat who leaves from his besieged headquarters towards exile and death.

Since I first saw it, almost ten years ago, I fell in love with the snapshot. It was taken with a telephoto lens, from a distance, by a photographer outside the scene who managed, however, to capture the farewell gesture of a man who, at 75, knows that he is about to embark on a journey of no return. The photo, by the way, refutes the statement made by the legendary Robert Capa: “If the photo isn’t good enough, it’s because you weren’t close enough.”