2023 left us with the bitter taste of goals that were not met: phrases that as the year progressed were losing their meaning; television reports that contrasted with everyday reality; speeches that resorted again and again to the United States blockade on Cuba and its negative impacts on our economy to justify its inefficiencies; slowness in making key decisions, incompetence, passive and active resistance to the changes that will necessarily have to be made no matter how much they try to delay them.

We also had denial of the obvious; search for new culprits no matter the costs; basic services in a spiral of deterioration that is difficult to reverse, not only due to lack of resources, but also of people, but above all due to the growth of the “culture of indolence” that not only exists in organizations but has unfortunately found a place in each of us. And perhaps the worst damage: the emptying of the country.

I’m not talking about mistakes; the country’s main leaders spoke about them. Errors are a natural part of decision-making. It is part of the risk that is run when working on phenomena with a high degree of uncertainty, or when one prefers to ignore what science teaches and what the evidence — and the data — show us. Indeed, we have also created the “culture of rectification of errors.”

The eternal rectification

So, goodbye to 2023, with its bitter taste. Welcome, 2024, a tremendously important year for me, as I will reach 70 years of life, fifty of which — counting those as a student assistant — I have spent working on what I like most, teaching Economics, always in the same place, my University of Havana.

2024, I still don’t know exactly why, brought to mind the year 1974, when I started teaching and discovered, the minute after starting my first class, that this would be the work of my lifetime.

It was also that year in which there was very intense work to prepare what would be the System of Management and Planning of the Economy (SDPE), which would be the most institutionalized form of “rectification” of those errors of “economic romanticism” that were committed in the 1960s.

Always mentioned among those “errors” were the aspiration to skip stages in socialist construction, the abolition of monetary-mercantile relations, the eradication of small private property through the complete nationalization of the economy, the “historical wage” and the contradiction of a significant amount of gratuities whose cost we all paid even if we did not realize it.

The SDPE would have a very short full life. It would later be “rectified” in the mid-1980s and languish alongside other systems that would also later be “rectified.” Much has been written from academia about all these processes, which also generated intense debates, long discussions, and great dissatisfaction.

Without goals, deadlines, or sequence

Let’s return, then, to 2024. On the one hand, we have a group of measures whose purpose declared by Prime Minister Marrero is to “restore the macroeconomic requirements that allow guaranteeing a favorable environment for economic growth, development and the process of socialist construction.”

On the other hand, we have the Economy Plan presented to the National Assembly and approved by it and therefore with the character of Law. In other words, whoever violates the Plan, violates the law. The same happens with the State budget: after it is approved it has the character of Law and whoever violates it, either because they underdeclare taxes or because they exceed expenses, violates the law.

The context in which these purposes must be carried out is that of an economy that has experienced a GDP decrease of between 1 y 2%; that has not recovered from the collapse of 2020; that faces sustained double-digit inflation dynamics in the last four years and is expected to reach 20-25% in 2024. An economy with a fiscal deficit increased by almost 50% in 2023 (98,363,800,000 pesos) while in 2024 this deficit will reach unprecedented levels (147,.391 billion pesos). Not easy.

I listed 52 measures/ideas/wishes. I see no goals, no deadlines, and no sequence for their application. I imagine that they exist and have been discussed in detail in other spheres. Some of them are measures whose execution and results are not, and cannot be, framed in the short term, given that they aim directly at the recovery of productive systems, which are currently deteriorated and without financial capacity.

Others, those that promote tariff benefits for enterprises that import raw materials and intermediate goods, will require sufficient guarantees to recover the capital invested and a coherent regulatory framework that generates the trust essential to assume such a risk.

In other words, these measures, undoubtedly very necessary, do not contribute in the short term to improving supply, something that should have the highest priority, if we take into account the fact that the weakness of supply is one of the recognized causes of inflation.

Less supply, more inflation

If the fight against inflation involves eliminating one of its main causes, it seems inconsistent to discourage the import of finished goods and even less so that the argument is that these goods are produced in Cuba, since even in the case that they were, their production volumes are far from the minimum volumes to satisfy demand.

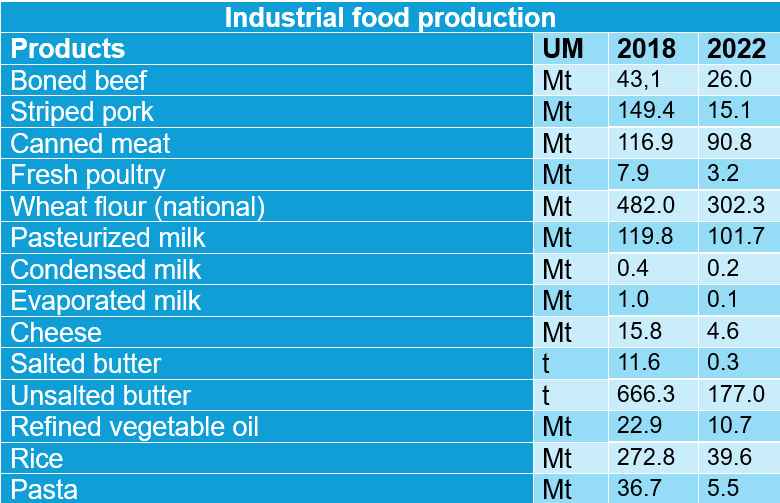

The performance of the physical volume index of industrial production confirms this sustained deterioration of the productive system for more than 30 years.

Source: ONEI, AEC 2022, table 11.1.

On the other hand, the import of final goods has been a structural characteristic of the national economy, caused by a structural deformation of our productive system, its weakness, and its lack of complementarity.

I have always wondered why, at a time when only three store chains monopolized the foreign exchange market for consumer goods, these enterprises did not dedicate a portion of their income to promoting productive chains with national industry and preferred importing even tomato puree and frozen fish from other parts of the world.

In short, everything that contributes in the short term to reducing the supply of final goods, whether imported or domestically produced, will have a procyclical, inflationary and regressive effect, since it will reduce the purchasing power of wages and income, affecting firstly the lowest income segments of our country, unless at the same time and in the same period, other measures compensate for this procyclical effect.

Who can import finished goods?

But it is true that there is another group of short-term measures that, if successful, could offset, at least in part, the unwanted effects of the restriction on imports, especially imports by MSMEs, such as those aimed at revitalizing the system of the stores selling in freely convertible currency, which will have to be done by importing finished goods! What an inconsistency.

This revitalization, which apparently will involve the opening of the freely convertible currency consumer market to foreign companies, whether wanted or not, could increase the dollarization of the economy, by helping to raise the demand for dollars and feeding back the devaluation of the Cuban peso, a result that contrasts with one of the declared priorities of the Macroeconomic Stabilization Program, namely: the “gradual de-dollarization of the economy.”

But, from my perspective, and given the circumstances that the national economy is going through, the opportunity cost of not doing it is greater than that of carrying it out.

The MSMEs, cooperatives, and self-employment during 2023 were a decisive factor in sustaining a part of the supply — they imported more than a billion dollars, most of it in finished goods1 — and thereby contributing to the moderation of inflation rates.

And where would inflation be if non-state actors had not imported that billion? Those hundreds of tons of pork, powdered milk, chicken, rice, sugar, wheat flour, tomato puree, sausages…. What national industry would have produced them?

Is it not more consistent with the emergency context that the country faces to generate incentives for those same actors to increase those imports that the national industry will not be able to produce in the short term? Has it been the imports of non-state actors that have prevented the national industry from increasing its production?

Who then benefits from raising tariffs and increasing sales taxes?

Were the ceiling prices what made it possible to moderate the dynamics of inflation or was it the increase in supply caused by imports in these non-state forms?

Will this collection make it possible to significantly reduce the weight of the deficit in the domestic product?

Let’s look at 2024. A group of productions have been contracted. Let’s do math:

Achieve greater participation of national food production in the Regulated Family Food Basket. So far, 22,000 tons of rice, 10,000 tons of beans and 10,000 tons of corn have been registered.

Source: MEP, Objectives and goals of the economy for 2024, Dec. 2023

Those 22,000 tons registered mean, if the commitment is fulfilled, that national production would guarantee 2.4 kilograms of rice/year to each citizen, based on 9 million people. Can the State cover the remaining need through imports when a ton of rice costs $690.9? Should non-state forms be prevented, made difficult, or discouraged from importing rice?

Inflation, dollarization

Another group of measures announced is aimed at encouraging production, from those that speak of “promoting cooperative production contracts with foreign investors and non-state economic actors that provide financing in foreign currency and raw materials,” to those that propose “increasing the participation of foreign investment, prioritizing food production” or “selecting forms of non-state management with liquidity capacity due to the possession of their own assets, credits or financial support from foreign companies, to carry out negotiating processes that favor linkages with state-owned enterprises.”

All of them go through three basic issues for any business: trust to start a business of a certain size; guarantees that the money invested can be recovered via dividends; regulatory framework that allows these new businesses to operate in conditions approximate to how businesses operate in the world. All three are possible to achieve, none of them require a cent.

Something that draws attention is the great absence of this intention of “restoring the macroeconomic requirements that allow guaranteeing a favorable environment for economic growth, development.…” None of the measures/ideas/intentions talk about rectifying the allocation of the country’s own investment resources! and drastically reduce its own funds dedicated to the construction of hotels; those that remain today with occupancy levels far from those that would allow the recovery of those funds within the planned period.2

The adjustment is undoubtedly necessary. But the order, sequence and distribution of its costs is debatable.

Of the measures announced until today, those that raise prices and rates will also contribute to the rise of inflation, the increase in dollarization, and a greater devaluation of the Cuban peso with regressive effects on the sectors with less income. Among other reasons because they fuel the inflationary expectations of all citizens.

It is also debatable to maintain a bureaucratic structure of the State that has shown signs of being neither effective nor efficient. Why not have started there?

Reduce subsidies, raise rates… These measures alone do not guarantee that the situation that the country faces today will not be repeated. More must be done, especially in that other direction, which is to increase the tax base, and enrich the business fabric by promoting and facilitating the birth of thousands of new SMEs and cooperatives. It is necessary to unblock the state enterprise once and for all and do it with all the urgency that is demanded.

These measures must be given dates and goals and place them in the correct sequence.

We have been immersed for years in an adverse situation that has become perpetual. Let’s hope 2024 will take away that bitter taste that these last five years have left in our mouths.

________________________________________

Notes:

1 In 2023, it is estimated that the import of consumer goods reached between 2.1 and 2.2 billion dollars Source: MEP, Objectives and goals of the economy for 2024, Dec. 2023.

2 In the presentation of the 2024 Plan, the distribution of investments by sectors does not appear.