The non-state sector and especially SMEs are today the focus of one of the sharpest debates of all those that characterize daily reality in Cuba. Somehow, and I think quite rightly, the space granted to non-state “actors” has been used to qualify/evaluate whether this reform process in which Cuba has been engaged for more than thirty years is more or less decentralized; if it approaches or moves away from the socialism that can be built today, taking into account our circumstances, external and internal; if it advances or if it regresses.

The scope of this debate and the polarization it has reached is a clear sign of the importance of the sector in the Cuban economy and society.

Some data on the non-state sector of the economy that help us visualize this importance:

- Today it represents around 15% of the GDP.

- It concentrates 35% of the total number of employees and employs more workers (1.6 million) than the state business sector (1.3 million).

- SMEs have generated around 250,000 direct jobs in these two years.

- Until May 9 of this year, there were a total of 8,012 SMEs, of which 7,842 are private, 105 state-owned, and 65 non-agricultural cooperatives. But in reality, the sector is much broader, we would have to add the self-employed workers, the artisans, the usufructuaries, the Agricultural Production Cooperatives (CPA) and the Credit and Service Cooperatives (CCS), the Local Development Projects (PDL), none of which are state-owned even when they do not qualify as SMEs because they are still enterprises and non-state enterprises.

- The sector has generated 4,788,500 dollars in exports and 270,294,100 in imports, of which 61% (164.8 million) were made by MSMEs.

The fact that private ownership is accepted in the Constitution of the Republic as one of the forms of ownership that function for the construction of Cuban socialism is, without a doubt, a regulatory milestone that sanctions the right of all Cuban citizens to have their own businesses.

It is something “innovative” in the socio-economic construction of Cuba and decisive for the very “life plans” of Cubans who go through trying to materialize their dreams in Cuba instead of seeking to make them come true outside of Cuba. It is also true for “family strategies” that also go through the same dilemma.

It is true that these “non-state” actors were conceived as complementary. This adjective is perhaps one of the first issues to clarify in any discussion on the matter, especially since it is relatively common to identify “complementary” as something of minor importance and, moreover, dispensable, even when the meaning of the adjective is another, namely, “that serves to complete or perfect something.”

In any economic system, completing and perfecting does not seem to be something unimportant and dispensable, especially when the state enterprise, which should be the driving force behind the reform and modernization of the country, has not been able to play that role. This has been the case in the last thirty years, in which for multiple reasons, some specific to the management of said enterprises and others associated with regulatory systems, have prevented it from fulfilling that role.

But, definitely, and even though the regulatory framework still leaves many gray areas, causing the uncertainty curve to skyrocket, the truth is that MSMEs have known how to take advantage of these spaces and have shown a great capacity for reinvention.

Let the MSMEs produce; let them be inserted in the local productive fabric; let them “help” increase the supply of national products, at affordable prices; for not so many finished products to be imported and for many more inputs and intermediate goods to be imported to generate that much-needed national production; let them export!, are among the demands for MSMEs today.

The truth is that some have managed to export and that some others have managed to insert themselves into productive articulations with state enterprises. Others have recovered production plants and infrastructure belonging to enterprises and other state organizations that suffered significant deterioration and threatened to be lost, after being “cannibalized” many times. There are anecdotes about it to fill many pages. But despite these sample buttons, dissatisfaction remains, and it feeds and is fed.

It would be worth remembering again that MSMEs have barely been formally born for two years, that this birth was delayed, with forceps and in a boat that barely manages to float.

They have already gone through the bitter experience of seeing how the regulations that created them, their regulation, is subjected to administrative interpretations such as the limitation of the corporate purpose, the elimination of the tax exemption in the first year of operations, the latent threat of having to pay a 10% tax on wholesale sales, which in addition to being clearly inflationary for the entire economy is unquestionably onerous and regressive, as well as contrary to the purpose of economic growth.

It is also worth remembering that during these two years MSMEs have had to fight against ideological prejudices that sometimes become almost insurmountable obstacles; against sectorial rules of the game that are sometimes based on the perception of “someone” who allows himself to ignore the regulation. And that they have had to “negotiate at a disadvantage,” caused by legal loopholes, and not infrequently they have lost opportunities while waiting for permits that were not necessary.

However, what has happened, to the surprise of some, is that where other actors have seen a problem, many MSMEs have identified an opportunity and have taken risks.

Let the SMEs produce! It is said and repeated easily and it can even become a slogan. However, the country’s macroeconomic and productive conditions help little in this regard.

Non-state forms of management are asked to import fewer finished products and more inputs, without taking into account that the devaluation of the exchange rate makes importing these inputs more expensive, paradoxically becoming an obstacle in the purpose of promoting national production, highly dependent on these inputs, which is why the state enterprises themselves face difficulties in “producing.”

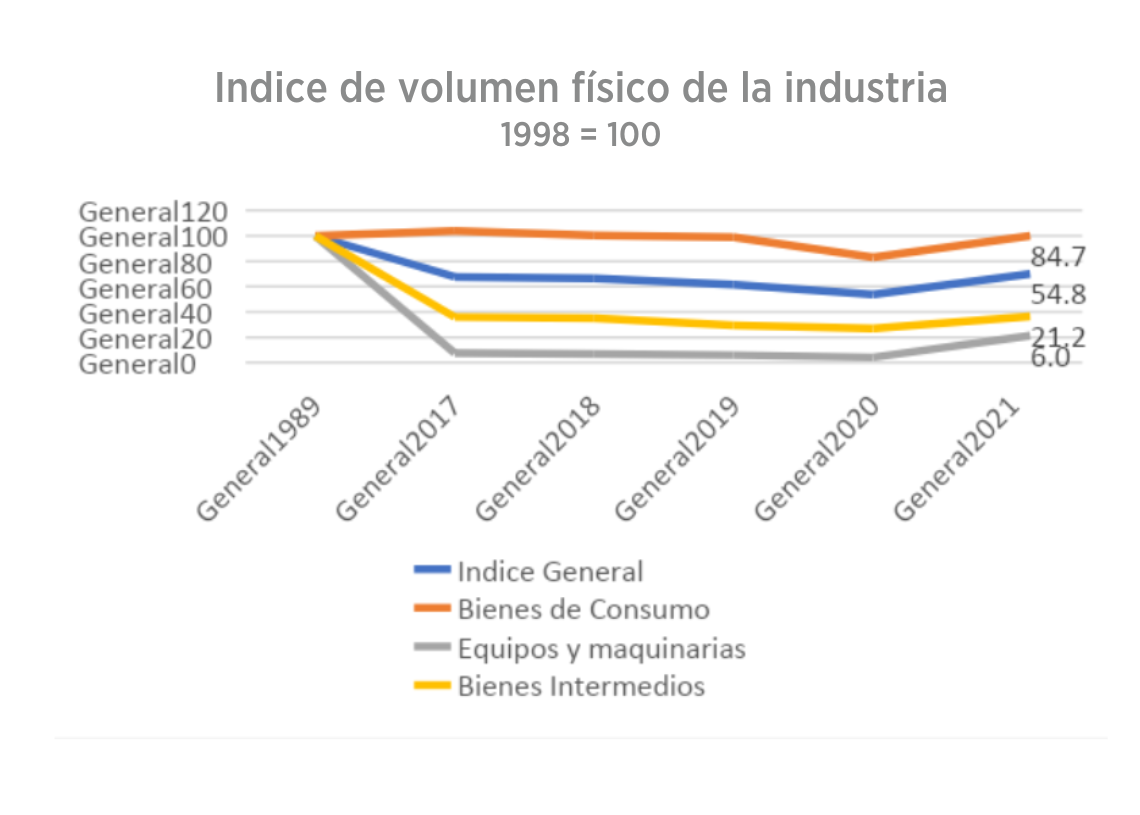

Indeed, if one looks at the data from the 2021 yearbook, it is possible to verify the drastic fall in the import of intermediate goods — with the exception of fuels, oils, minerals and related goods —, from 2018 to 2020 by 30% while the fall in the import of capital goods was 40%, which largely explains the reduction in the dynamics of production and the deterioration of the state business system.

General index / Consumption goods / Equipment and machinery / Intermediate goods

Source: Statistical Yearbook of Cuba, 2021. Table 11.2.

In the case of food, this fall was greater, close to 65% in relation to 1989.

It is also forgotten that this dependence on the import of intermediate and capital goods is a structural deformation of the national economy, a failure that no strategy has been able to reverse, not even when we had cheap credit and fair prices and it was possible to reach a share of industrial production of more than 30% in GDP and state-owned enterprises enjoyed advantages that will never be reproduced again, including excessively soft tax treatment.

It is true that this great deterioration is also an opportunity for improvement that, if well managed, could have important impacts even when the investment was almost marginal, but it is an opportunity for the entire Cuban business system, for state enterprises, for SMEs, for foreign investment. It is necessary to generate incentives, trust and transparency.

If SMEs are to “produce and export” then proper rules of the game will be needed to induce these enterprises to do so.

Isn’t it possible to have a more proactive tax policy towards those SMEs that produce and/or export? Isn’t it possible to build a tax regimen similar to the one that exists in Mariel for those who take that risk?

Why not modify the tariff regimens for certain products that are essential “inputs” in specific productions of interest to the country and for the import of certain equipment that also contribute to producing final goods?

Why not modify the profit tax, that of 35%, for those SMEs that develop and produce goods and introduce exemptions for those that produce food?

Why continue delaying the creation of an Industrial and Agricultural Development Bank?

Why keep postponing the procedure for the creation of ventures between foreign capital and MSMEs? Why not make it much more transparent and agile than those that exist today in Law 118? Why not decentralize the approval of projects less than a certain amount of dollars for local governments?

Why not create microfinance funds from remittances or with the participation of foreign banks to promote businesses aimed at the production of goods and especially food?

Why not continue expanding the activities that non-state forms of management can develop?

Why not take better advantage of them in our perpetual fight against the U.S. blockade?

WHY TAKE SO LONG IF SO MUCH HAS BEEN DISCUSSED, WRITTEN AND PROPOSED? If the evidence is demonstrating the need and urgency of expanding the participation of these actors in the national economy?

When reviewing what is published on social media, it is possible to verify that there is a manifest intention to make SMEs the bone of contention. It has already passed in the mid-1990s and the birth was delayed thirty years.

There is an intention to turn SMEs into the “enemy of the people” and the denial of the values of socialism, and thereby demonstrate the “government’s mistake.” The intention to use them as a scapegoat for the failure of the monetary reorganization program is evident, as the causes of inflation, inequality and poverty, all phenomena that already existed before their birth.

They also want to be presented as one of the reasons for the meager progress in the transformation of the state business system. It is even wanted to present them as the back door through which “enemy activity” unfolds.

There is an intention to use them to divide. But it’s long since time to add, to find the least common multiple.

Productive policies are required that combine the efforts of all the actors of the national economy. Let’s change the rules of the game and SMEs will produce.