Willy Castellanos (Havana, 1959) has a Bachelor’s Degree in Art History from the University of Havana (1994). His final academic exercise was dedicated to the reappearance of the nude in Cuban photography, in the period between 1982 and 1993. He is also a curator and artist. He is a self-taught photographer, although he was accompanied in his initiation into the profession by Chino López. In Cuba, he published, as a freelancer, photos in the magazines Bohemia, Tablas and Cuba Internacional, among others.

In November 1994 he emigrated to Buenos Aires, where he lived for seven years. There he worked at the magazine Pugliese (1999-2021) and collaborated with the newspapers Clarín and La Nación.

Then, in 2001, he settled in Miami, where he lives and works, although some of his curatorial and artistic projects take him to various countries.

Together with Adriana Herrera Téllez, he founded the Aluna Curatorial Collective in Florida, which has basically dedicated itself, with exhibitions of different artists, to promoting “non-hegemonic dialogue on the relationship between art and society.”

His works have been exhibited in Argentina, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Peru, and the United States. His solo exhibition Éxodo: documentos alternos, which took place at the Centro en Cultura Español in Miami, won the Miami Arts Foundation award in 2014 for the best cultural event held that year in the city. He is currently participating in the Cincinnati FotoFocus Biennial backstories, where he has the solo exhibition Éxodo: documentos alternos (1994-2024), which can be seen until the end of December.

I was familiar with Willy’s work on the 1994 rafter crisis. His photos from that time, dramatic and truthful, were limited to showing, from a committed and empathetic perspective, the painful human drama of those who launched themselves into the unknown with precarious means, without having the slightest idea of what it means to face the Gulf Stream, that willful and colossal torrent that Hemingway baptized as “the immense blue river.”

He shares some of that here, along with other works that will give us a vision of his artistic range and his concerns as a conscious inhabitant of this planet.

As a statement or declaration of an artist, he sent us these words:

“One of the practices that most motivates me in my work has been the questioning of the archive, that system of statements about the past that, as Foucault understood, is usually put together by power and assimilated collectively. And photography, by its very nature, due to its proximity to the archive, is perhaps the ideal medium to question it, and one of the most suitable for developing a series of artistic practices capable of generating new stories and alternative archives. Series such as Éxodo: documentos alternos (2014) approach history as a narrative in full construction, considering that the past is open and its perceptions can be destabilized with the use of images that, often and with increasing recurrence, are photographic. In some cases, this destabilizing potential is found in direct documentary works. In others, it is based on a diversity of intervening procedures in photography. Both artistic possibilities can expand the scope and nature of the medium and create ways of infiltrating the archive of memory and, therefore, of seeing the present and reimagining reality.”

Let us give way to the photos and comments that Willy Castellanos wishes to share with us.

The multimedia installation Dry Feet/Wet Feet, 2014, is named after the policy implemented during the Clinton administration as a solution to the 1994 rafter migration crisis. This law allowed Cuban migrants to remain in the United States if they touched land (dry feet), while those intercepted at sea were returned to the island (wet feet). The work uses a large-scale photograph printed on fabric and fragmented to create an immense mural of the sea. Each segment ends on the ground, where acrylic containers filled with water and sand (the physical elements that defined this migration policy) alternate. The piece has a multisensory dimension: when viewers approach, they hear the original recording of the voices of a group of rafters leaving the island from the shores east of Havana.

The “wet feet, dry feet” policy was repealed on January 11, 2017 by President Barack Obama. The measure temporarily reduced the flow of Cuban immigration by this route. However, the practice of crossing the Straits of Florida in rudimentary boats has continued to this day. In recent years, the number of Cubans who have entered the United States through the Mexican border has significantly exceeded the figures recorded during the Mariel exodus in 1980 or in the days of the so-called Rafter Crisis of 1994.

***

First of all, there is The Sea. An immense and compact mass of blue limbo. First clear, then sky blue, sometimes turquoise, or if not blue, tremendously blue. Within it, freshness and lightness. Outside of it, the stinging sun, the breeze, and the uncomfortable sensation of salt on the skin. For those of us who were born in the port city of Havana, and perhaps for many Cubans, the sea is a constant obsession. Every day we walk towards or away from the sea, parallel to the coast, on the way to the mouth of the Almendares River or, simply, crossing the bay, that “other sea,” a tiny ocean and forest of cranes, a convenient refuge for old barges and swarms of passersby and tourists. The sea surrounds us and defines us, its contagious aroma penetrates pores and senses. The sea limits us, envelops us; the sea encloses us: it is the Blue Wall.

***

Photographing with a telephoto lens is scrutinizing the intimacy of the other, participating in a story to which you have not even been invited. The photographed do not perceive the presence of the photographer, who inhabits a fictitious dimension of reality, benefiting from a false, purely optical proximity. If the image reconstructs history, how many of these “intrusions” make up the documents we have of all things today? Is photography perhaps an instrument of colonization, a way of appropriating another’s space by turning it into publishing material, into simple data to be disseminated?

I wonder if the act of documenting the crudeness of reality does not require a kind of silencing of the aesthetic pretension of photography. But at the same time, before this scene, I review a myriad of images: Gericault and his “Medusa,” Thor Heyerdahl and the Argonauts. I look from a prism that superimposes the distant and the close, but also a prism that includes the trembling before the threat of death, and the fascination for the epic of those who face it in extreme situations.

***

The global village has placed its poles of abundance in the northern hemisphere, mobilizing in that direction the incessant flow of the less favored. If the utopian impulse that unleashes the journey points — like a stubborn compass — toward that hemisphere, disillusionment, and its shipwrecks become “no-man’s lands,” borders to be crossed. Thus, Thomas More’s island still seems to be drifting, at some imprecise point in the sea of resignation.

But the images, the photographs, at what latitude do they move? Toward the epicenters of power and its stories or toward the south, on the borders of dystopia and their rebellions? Is it perhaps in the margins of those small stories (like the one in this photo) that are woven secretly and inserted like wedges in the anonymous archive of everyday life?

Documents, testimonies, evidence…, what notions intervene in the construction of that immovable concept that we call “History”? Who writes the great stories of human experience and what episodes are included in this narrative of knowledge destined for consumption and dissemination?

***

I cannot reconstruct a credible story about this photograph, except from my fictions. It lacks information, perhaps more precise elements or situations. It lacks contextual marks and other data necessary to reconstruct the paradigm of photography; or, better said, to stage the event based on documentary logic. It is one of those images that need (like crutches) other contiguous images to signify, or perhaps a text, like the one I am writing now.

Perhaps this photograph will never be published in the press, but it still fascinates me. I am captivated by the girl’s serene gaze, her boldness in front of the camera and the intruder holding it. Would she travel on that boat, reckless, inflated with illusions? I think now, after so many years, that she stayed on the island, that that afternoon she only accompanied her family to say goodbye. In any case, this photograph is the document of my fictions: the open notebook of an unfinished story where no possibility is definitive; a story lost in the limbo of memory and reality.

***

I took this photograph on the coast of Havana, during the Rafters Crisis of 1994. In the scene, a young rafter offers his sandals to a friend before embarking north. Perhaps the young man thought he would not need them on the high seas, and that once in the United States he could buy new ones of better quality. This is my interpretation of the scene, although I cannot say for sure that my story is true. After a few minutes, the group dispersed and I was unable to obtain more information than what is perceived at this moment by looking at this photograph. In my version of the story, these sandals are an expression of brotherhood and an inheritance.

This photograph has been little disseminated. It is a silent folder “wandering outside” the archive, or within a “dead” archive (the set of photos I took that day). This story does not contribute to the knowledge we have about footwear, nor to the reconstruction of a notion of history associated with it.

***

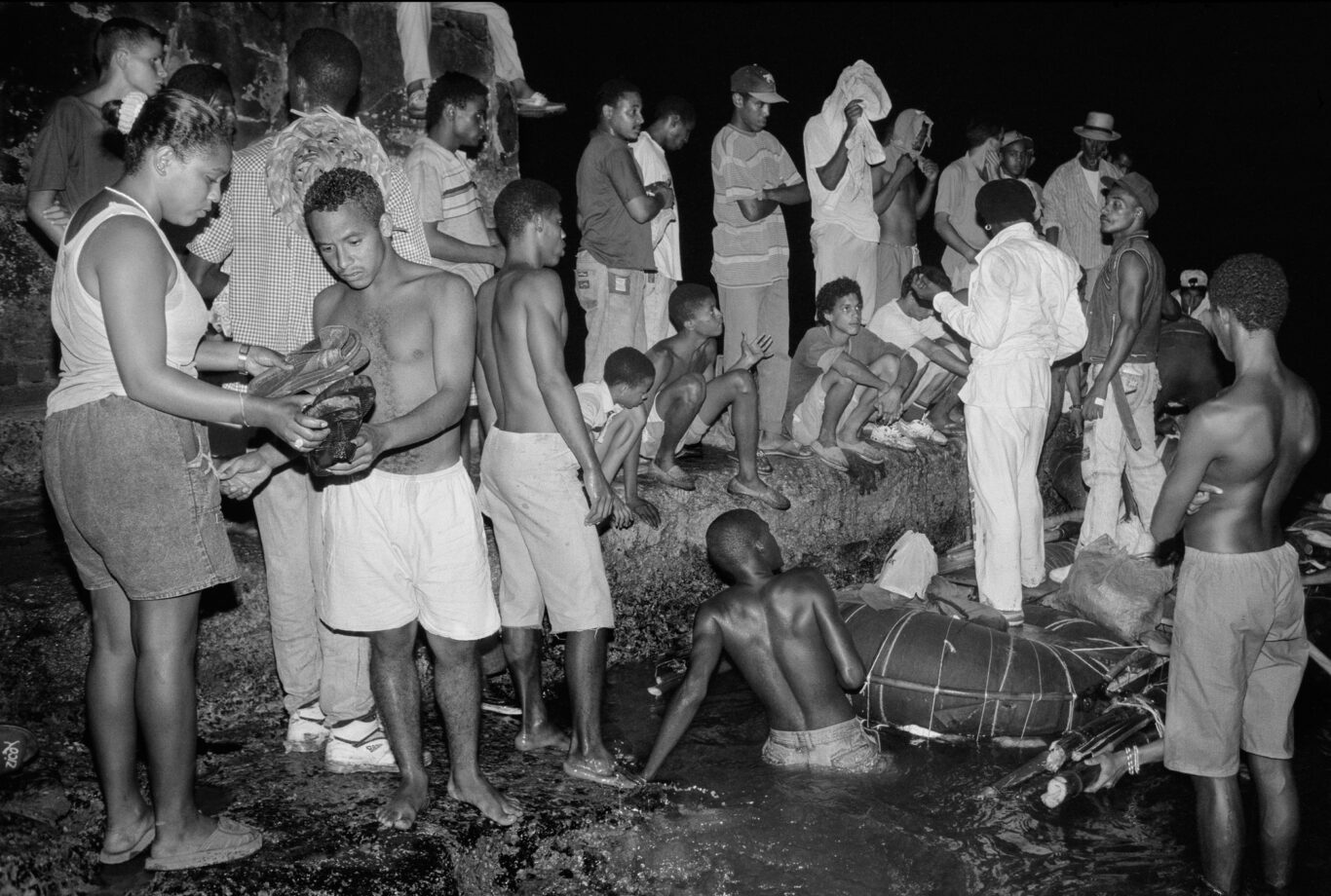

I often think of Las babas del diablo, the Cortázar short story, when I look at the photos from that dark night in 1994. I photographed “blindly,” guided by the glitter of the flash that illuminated the coast for fractions of a second. Behind the deep veil of the night, I heard the creaking of the wood and the sound of the sea in the frenzy of the crowd.

Only days later, when I printed the negatives, was I able to visualize the real dimension of the chaos. The image moved me, and my surprise was greater when I discovered, among so many, the profile of a childhood friend, missing from the neighborhood for months. Had he given up on the trip — as he later told me — or was he simply another of the many stowaways who tried to board the boat?

Chance, contingency, causality…what keys moderate the eventuality of the photographs? Who is the eventual owner of the images? The operator who surprises — by chance — the moment, or the subjects who stage in that instant a drama that will mark them for the rest of their lives?

***

A dear friend wrote that these photographs were a premonition of my own departure. “Why didn’t you go on a raft during those days?” I was asked recently. I suppose I chose to stay and portray the experience of the exodus of my own people in these images that, in a way, are illegible or transmit the opacity of their own circumstances.

What is this young man doing floating adrift, as if he were accompanying his friends on the raft in a summer pastime? This scene, which seems absurd, is indecipherable. I read a quote from Feuerbach that anticipates Benjamin: “For the present age, which prefers the sign to the thing signified, the copy to the original, fashion to reality, appearance to essence, only illusion is sacred, truth profane.”

Perhaps the act of turning a human experience that is unspeakable and not transmittable into “just an image” is a way of profaning it. And yet, from all the absurdity that this photo and the act of taking it go through, there is a remnant for which I continue to believe it is necessary.

***

In the language of the Hopi — the ancestral people who inhabited the central area of the United States — ”Koyaanisqatsi” is a word that means “life out of balance.” In 1982, filmmaker Godfrey Reggio used it as the title for the first film in an experimental trilogy that documented the loss of balance in this “world we live in,” as he put it. Regreso a “Koyaanisqatsi” — a series composed of photographs, installations, and objects — revisits the spirit and documentation of this urban paroxysm through another process of visual investigation (the 4 x 5 negative camera), in a series made in the city of Miami, in various scrap metal collection and recycling facilities. Traditional “large format” cameras — a medium that is practically obsolete — impose, from the very process of recording, a timely slowness of gaze and action, while guaranteeing a sharpness of detail superior to the digital medium, with its rapid recording speeds. And why garbage dumps? Because never before, in the entire history of human civilization, has waste constituted such a threat as the one we face at this moment.

I have documented, in visits spaced out over a year, the testimony of the culture of the obsolete and the speed with which we use, accumulate, and discard objects, in a direction diametrically opposed to the preservation of the environment. Photographing junkyards, I have also recorded the formal beauty of garbage. I have rescued found objects and helped them ― recycled them ― to give them a new life, as a gesture of the imagination. And I have asked myself the question that I extend with a clear awareness that the time of resistance to paroxysm is getting shorter every day: How can we oppose planned obsolescence, cumulative excess, the frenzied speed of life? I have returned from these dumps with another clarity about the urgency of a common life that is slower, less voracious and destructive, fuller of humor and imagination. And, above all, capable of building a sustainable culture for our own species and for all others as well. It is the only way to change the time that is coming, that time where, according to Chief Seattle, “the end of living and the beginning of survival” would begin.

***

In February 2020, just before the global alarm of the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, I decided to visit the town of Agbogbloshie, located in Accra, the capital of Ghana. In international press reports, the place had the reputation of being the “largest existing dump of electronic waste,” one of those spaces where the world’s waste from our culture of accelerated obsolescence ends up.

In the city of Miami, United States, I had photographed — with a large-format negative camera — the enormous mountains of metal garbage that accumulate on the banks of the river, in those centers where metals of all kinds are recycled. The observation of the garbage dumps allows us an axial vision of current societies and their dynamics, and with that record, I intended to gather an initial archive to open a debate, in the art circuits, on “the speed with which we use, accumulate and discard objects in a direction diametrically opposed to the preservation of the environment.”

But in Africa — the continent where humanity took its first steps — my photographic approach changed substantially when I was confronted with a much more complex and essentially dramatic reality: a scenario marked by the intersection of overwhelming problems such as the overaccumulation of waste, the environmental damage caused by its processing, the terrible living conditions faced by the locals, and the need to conceive stable sources of work that guarantee decency and family sustenance, among many other aspects. So I left aside the metaphors of the landscape to focus on direct social documentation, capable of containing my interrelation with the territory and its problems, as well as the links I established in those days with its unique inhabitants. On our first day at the Agbogbloshie dump, the portable air pollution meter reached 375 on the European Air Quality Index (AQI) scale, a reading that is more than three times higher than the levels of pollution that humans or other species can tolerate.

***

Impresión / Atardecer con manglares contains six photographs taken in the same place and from the same position, during the time necessary to record the changes in light at dusk, in the stillness of a lagoon in the Everglades of southern Florida. With slight variations in the diaphragm, the camera on a tripod, I was able to synchronize — as the impressionists did — the cycle of the sun in the lights of dusk.