The first time I taught at Columbia University, in 1991, I discovered that my students didn’t know the United States had a naval base on Cuban territory.

I remember their faces when I showed them its location on the map, at the very entrance to one of the island’s two largest pouch-shaped bays, and which had lasted 90 years. That’s not counting the five years of previous military occupation since the Splendid Little War (Teddy Roosevelt dixit) that their history books still called the “Spanish-American War.” The most surprised in the classroom, by the way, were the Cuban-Americans.

That naval base doesn’t exactly date from the Cold War, but from the era of U.S. territorial expansion at the expense of Latin American and Caribbean countries; and it wasn’t imposed to contain the rise of communism or other specters, but rather by the Platt Amendment. And it’s still there, even though that Amendment was abolished 90 years ago. So, if we’re talking about anachronisms, none can compete with that naval base at Guantánamo.

Many territories have been acquired, annexed, leased, colonized, and dominated by a foreign power, at least since the 18th and 19th centuries. And some have been reverted to the full control of the leasing state. For example, the cases of Hong Kong (1997), Macau (1999), and the Panama Canal Zone (2000).

In terms of duration, territorial lease treaties have varied, from those that provide for a fixed term to those agreed upon in perpetuity. And some have been converted. For example, the treaty ceding rights to the island of Hong Kong between China and the United Kingdom and the one leasing the Canal Zone to the United States were originally in perpetuity; in both cases, a fixed-term treaty was renegotiated.

The conditions affecting these renegotiable treaties are characterized by certain common features. For example, the agreement between a powerful state and a weak one; the fundamental change in the original circumstances (in legal jargon, rebus sic stantibus); the lease without a clause relating to its termination; the validity of the object or purpose of the treaty; or the changes in international law over the years.

In other words, a territorial lease can be terminated, regardless of its originally intended duration, according to the international law doctrine currently in force regarding unequal treaties, because it was conceived between a dominant state and a dominated state, because of the emergence of a peremptory regulation of international law incompatible with the territorial lease without a termination date, as well as because of a fundamental change in circumstances or a material breakdown of the order advocated by the lease.

In the case of the territory at the mouth of Guantánamo Bay, the return to Cuba or “the negotiation of a new treaty on mutually convenient terms” by the lessee is only permitted, in the words of the Helms-Burton Act, “as part of the relationship with a democratically elected government in Cuba.” That is, it is politically conditioned.

Rewinding this film, we can find some scenes forgotten or ignored today.

As is known, the 1903 Treaty of Relations was derived from the Platt Amendment; and this, in turn, stems from the logic invoked by the United States as “responsibilities assumed by the signing of the Treaty of Paris” in 1899, officially ending the war with Spain and its colonial presence on the island.

It is well-known that despite having fought for thirty years against the mother country, Cubans were not present at the negotiation and agreement of the Treaty of Paris, from which the sovereignty of the new republic, won by the independence movement, was to emerge.

The 1903 Treaty of Relations states that “in order to preserve the independence of Cuba, and to protect the Cuban people, as well as for its own defense (that of Cuba), the government of the island will sell or lease to the United States lands necessary for coaling or naval stations at certain specified points, which will be agreed upon with the President of the United States.”

Initially, the United States sought to purchase not only Guantánamo, but also Bahía Honda, Cienfuegos, and Nipe. Despite the asymmetry of power and the subordination created by the Amendment, the Cuban government managed to limit the first two bays to a single lease. We could recognize that government’s merit.

Guantánamo’s strategic value to the United States increased rapidly as the Panama Canal opened in 1910, and maritime routes and traffic in the western Caribbean multiplied. From then on, the prevailing view of the naval base at Guantánamo (which they began to call “GTMO”) assigned it a key role in the defense of the southeastern coasts of the United States.

Given the crucial role of naval installations in the Caribbean geopolitics of the early 20th century, expanding GTMO’s territory outweighed interest in Bahia Honda, on the northern coast. Thus, in 1912, an agreement was reached to close it in exchange for expanding the naval base in eastern Cuba. GTMO’s total area expanded to 117 square kilometers of land and water, slightly larger, say, than Manhattan Island.

So instead of $2,000 a year being paid for the bases, the United States increased the lease amount to $5,000 a year, which it maintains today. Naturally, the Cuban government stopped cashing that check in 1959.

Reviewing the documents that have marked milestones in the legal and geopolitical regime of GTMO involves tracing back relations between Cuba and the United States for more than a century.

What does the lease agreement (or agreements) say?

In 1903, its primary service is to supply the United States Navy. It specifies that it will not be used “for any other function.” And that “vessels engaged in commerce with Cuba will have free passage through the waters included within the territory of the base.”

The 1903 agreement also states that the United States will exercise full jurisdiction and control, not sovereignty, over these areas, with the right to eventually acquire any other landed property around them for public purposes related to the operation of the naval base.

Thus, it definitively recognizes the continued sovereignty of the Republic of Cuba over the land and water areas of that territory, over which it has only “jurisdiction and control…in accordance with the provisions of this agreement.” Both the 1903 agreement (Article 3) and the 1934 agreement.

It is added (point 3 of the regulations) that the United States agrees that “no person, company or association shall be permitted to establish or carry on commercial, industrial or other enterprises within said areas.”

Therefore, establishing a business, installing a private commercial platform, or any other project, such as turning the territory of GTMO into “the Singapore of the Caribbean,” contradicts the terms of the 1903 and 1934 agreements, which the United States invokes to try to legitimize the very existence of the naval base. According to those documents, nothing else may be done that does not fit within the scope of a naval base.

Finally, the 1934 Treaty of Relations specifies (Article 4) that “fugitives from justice who escape the jurisdiction of Cuban law and who seek refuge within said areas shall be handed over by the United States authorities upon request by duly authorized Cuban authorities.” In other words, it prohibits the granting of asylum to persons fleeing Cuban justice; logically, since GTMO is not “United States territory.”

Regarding the legal and political circumstances of the 1934 Treaty, it is worth remembering that it was endorsed by the Cuban government in place on June 9 of that year, when the president was Carlos Mendieta (who governed for one year and ten months) and Congress was composed of the Popular Party, the Liberal Party and others that ceased to exist in post-1940 Cuba.

The archaic nature of this Treaty of Relations is confirmed by its other content. Although it does not include the most blatant articles of the Platt Amendment (the right of the United States to intervene in Cuba, to control its foreign relations, etc.), it does address (Article 2) the point of the Amendment referring to preserving “the acts carried out in Cuba by the United States government during its military occupation of the island.” In other words, according to this Treaty, the decisions taken by the intervening government between 1898 and 1902 remain in effect.

The nature of the 1934 Treaty is enshrined when it stipulates (Article 3) that “until both contracting parties agree to its modification or the abrogation of the stipulations relating to the lease,” it will remain the same as it was in 1903. This places the naval base in a kind of legal limbo, supposedly outside the scope of international law. As long as “the United States does not abandon the naval station or the two governments agree to modify its present boundaries, it will continue to have the area it had when it was signed.”

From all of the above, it follows that the legal regimen, political foundation, and strict compliance with the current military function of GTMO are, at the very least, spurious and have been violated time and again, on their own terms.

As is known, the base has been used since the 1990s to concentrate rafters (undocumented migrants), mostly Haitians, Jamaicans and Cubans, and to keep them confined there by decree, outside the law and the courts.

It has served as a prison for suspected terrorists (Taliban), also outside the law and courts of the United States, as well as outside the regulations and controls in force in that country’s prisons, and applying methods that violate all established minimum conditions of confinement and the use of torture.

It recently opened a concentration camp for deportable people, where immigrants who have entered the United States legally and maintain their documentation are mixed with common criminals.

Is there anything that can be done about this naval base, in terms of international law and policy?

In a now-declassified internal document from February 1962, the State Department’s legal counsel prepared a contingency plan in case Cuba took the naval base issue to an international court.

This plan was limited to reaffirming the contents and legal validity of the 1934 Treaty; emphasizing that the United States “only maintains jurisdiction and control over the territory of the base”; and countering that Cuba retains “its sovereignty.” With that, as a wise farmer might say, they were clearing their chests.

However, the arguments in that plan are interesting. They are the ones that the United States could take to an international court, should Cuba resort to this option.

According to these legal advisors, the doctrine of fundamental change of circumstances “has never been endorsed by an international court” and “leading authors of international law say that the doctrine should be applied only by agreement of the parties” or through a court decision.

Of course, the United States is not usually prepared to respond before an international court. Its main argument has been to throw it away. However, that is not enough reason for the rest of us to think the same.

Although no international court has ruled on the legality of GTMO, there have been qualified judgments. For example, by the UN.

The assessment of the UN Legal Adviser following the outcome of the Cuban Missile Crisis in November 1962 challenges the U.S. argument based on the existence of a treaty, the 1934 treaty, which remains invulnerable to any attempt at renegotiation. He asserts that the purpose of that treaty, “to protect the independence of Cuba, its people, and defend the country,” contradicts the U.S. hostility toward that independence and is obsolete, as it “endangers the existence or vital development of one of the parties.” He concludes that only renegotiation of the treaty can offer a satisfactory and fair solution, citing as an example the dispute between Egypt and the United Kingdom (1947) regarding British troops in that territory, through a claim before the UN Security Council.

Since President Obama never fulfilled his promise to close the extraterritorial prison for accused terrorists installed in GTMO, which remains available now to confine Donald Trump’s deportees indefinitely, beyond U.S. law and courts, our topic returns to the front pages, with increasingly obscure political, legal and ethical overtones.

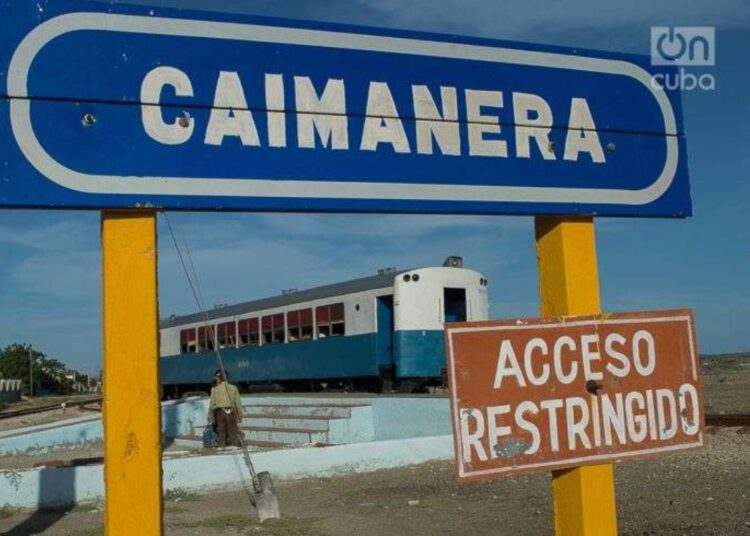

Could Cuba formally present the issue of the U.S. Guantánamo naval base to the Security Council? Not only as an old claim to effective sovereignty over part of its territory, but also as a human rights claim, given that the base blocks Guantanamo residents’ access to their main natural resource, in the poorest region of Cuba, by preventing the exploitation of its main bay.

Instead of a one-sided “Caribbean Singapore” imposed in violation of its own rules, would the United States be willing to sign a new treaty (with an expiration date) that would dismantle a naval base, long out of service to U.S. defense, and in its place create a binational authority that would foster a consortium of free trade, marine environmental protection, climate monitoring, higher education, and public health, benefiting not only both countries but also their Caribbean island neighbors? Would Cuba accept it?

A utopia, you might say. Well, I’ve heard that before. And yet.