I remember as if it were yesterday the session of the tripartite conference on the Missile Crisis, in January 1992, when Fidel Castro evoked Kennedy’s death.

Around a very long table were gathered the surviving characters of that event, when we had been on the verge, thirty years earlier, of “thermosnuclearizing everyone on the planet” (Retamar dixit). General Gribkov, who planned the deployment of the missiles; Secretary of Defense McNamara, who proposed the air-naval blockade (“the quarantine”); Commander Sergio del Valle, Chief of Staff of the Revolutionary Armed Forces in 1962, together with former deputy directors of the CIA, Kennedy’s advisors, experts from the three delegations. I was among those accompanying academics who were there.

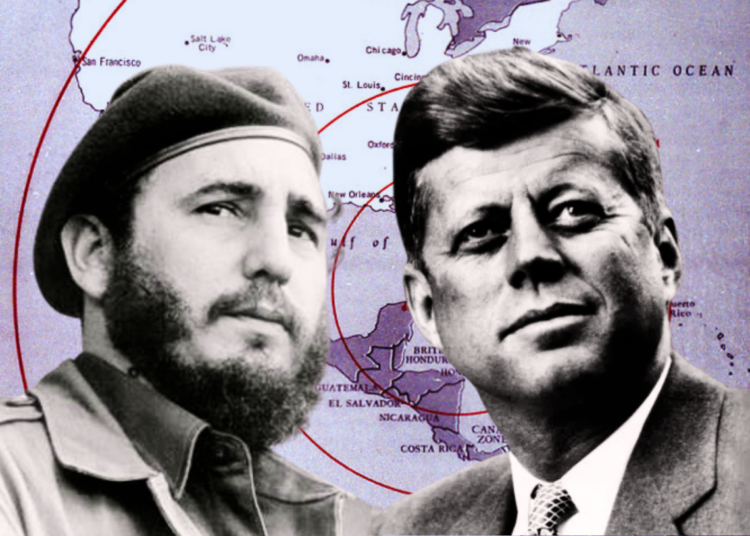

Fidel then recalled JFK’s talent and courage, his leadership ability. That his Alliance for Progress towards Latin America and the Caribbean had been a brilliant idea. And that his handling of the Missile Crisis had consolidated that leadership, so he could have been the president in the best position to rectify U.S. policy towards Cuba.

Fidel had had proof of that ability on the very day of his death.

He said that on the morning of the assassination, November 22, 1963, he was talking to the French journalist Jean Daniel, who was visiting Cuba on JFK’s behalf. According to what Daniel had been asking him, Fidel had had the impression that JFK was exploring the possibility of dialogue. To what extent had the Cuban leader been aware of the risk we had run ― the journalist asked him ― when the news of the attack arrived.

Fidel paused, to wonder if Daniel had ever written about that conversation. I remembered that Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a personal friend, biographer, and advisor to JFK during the Crisis, with whom we had been working on the organization of the Conference, had sent me a text that the Frenchman had published in The New Republic, just a year after Kennedy’s death. So I pressed the microphone button and commented on it to Fidel. He turned to the right side of the table, where I was sitting, and asked me what I said. At that moment my mind went blank.

Almost instantly, Schlesinger, who was on the same side of the table, pressed his button and telegraphically commented on Daniel’s version in his article “When Castro heard the news.” Some aspects not mentioned in that brief comment, and others that came to my mind after the embarrassment, have helped me reconstruct that key moment in U.S.-Cuba relations when the conflict structure would be defined for posterity.

According to Daniel, he and Fidel had spent an early morning talking about relations, three nights before. In that first session, shortly before the assassination, the comandante had constructed a harsh argument about JFK’s war against Cuba, including the Bay of Pigs invasion, the paramilitary actions of the counterrevolution, the Escambray uprisings, the blockade, the threats of invasion during the Missile Crisis, the assassination plans against him. He held him personally responsible for everything.

Fidel had commented that, ultimately, if he were killed, his influence in Latin America and “in the entire socialist world” would increase. That the most important thing was not his life, but peace in the hemisphere. For this to happen, a leader would have to emerge in the United States capable of understanding the explosive realities of Latin America and facing them before they exploded.

However, he had immediately acknowledged that “Kennedy still has the possibility of becoming, in the eyes of history, the greatest president of the United States, more than Lincoln, the leader who would finally understand that there can be coexistence between capitalists and socialists, even in the Americas.” He mentioned that, for Khrushchev, Kennedy was a man with whom one could talk; and that other leaders had assured him that this objective would have to wait until his reelection. “I also believe that he has understood many things in the last few months. And ultimately, I am convinced that any other would be worse.” Finally, Fidel mischievously told him that, if he met Kennedy again, he should tell him that he was willing to declare Goldwater [the Republican candidate] his friend if that would guarantee JFK’s reelection.

In addition to the nuances mentioned, Daniel’s description of Fidel’s reaction and his conduct after learning of the attack is revealing, from here and now.

“It’s bad news,” he had repeated. He commented on the alarming lunatic streak in American society, and that it could well have been the work of a madman or a terrorist.

When the fatal outcome became known, Fidel stood up and said: “Everything has changed. Everything is going to change. The United States occupies such a position in world affairs that the death of its president affects millions of people in every corner of the planet. The Cold War, relations with Russia, Latin America, Cuba, the black movement in the United States…everything will have to be rethought. I will tell you one thing: at least Kennedy was an enemy we had become accustomed to. This is a serious matter, extremely serious.”

And he added: “Now they will have to find the assassin quickly, but very quickly, otherwise, you will see that they will blame us. Tell me, how many presidents have been assassinated in the United States? Four?” “I have always opposed such methods, first of all, for political reasons. When we were in the Sierra, some revolutionaries wanted to kill Batista, to end the regime by beheading him. If Batista had been assassinated, he would have been replaced by a military man who would have made the revolutionaries pay for the dictator’s martyrdom.”

When it was later said that Lee Harvey Oswald, the assassin, was a spy married to a Russian woman; and then that he had been a member of a solidarity group with Cuba, Fidel commented to Daniel: “They have no evidence that he is an agent, an accomplice. But they say he is an admirer, to try to associate him in people’s minds with the name of Castro and the emotion aroused by the assassination. This is a publicity method, a propaganda device. Surely everything will soon pass. There are too many competing policies in the United States for a single one to be imposed universally for a long time.”

Daniel ended his article impressed that, despite the Bay of Pigs invasion, the Missile Crisis, and the still-living armed counterrevolution, the Cuban government publicly expressed its mourning for the death of the U.S. president.

Investigating the presidential libraries, where secret documents are kept, there is evidence of the exchange that, since remote times, has existed between instances of both sides, through a host of actors (and actresses), in an almost always invisible flow of formal, but above all informal, channels, which I have called elsewhere metadiplomacy.

The mission personally entrusted by JFK to the French journalist, an example of this metadiplomacy, was part of a series of secret exchanges extended throughout 1963, and derived from the interest of both parties to find alternative ways to the collision course that had dragged us to the brink of global thermonuclear war a few months earlier.

Both JFK and Fidel Castro began to move in that direction, with actions, some of them even public, that expressed different attitudes, and a willingness to negotiate and understand. Although this tendency to explore a different path to the ultimatum did not completely disappear after JFK’s death, it did not survive the polarity of the 1964 presidential campaign, where Cuba once again became, as in 1960, a test to measure how soft with communism the other was. The olive branch that was beginning to emerge would finally be buried by the escalation of the invasion called the Vietnam War and the landing of marines in the Dominican Republic in 1965.

Remembering the situation of JFK’s assassination is relevant because it has come back to the fore these days when President Trump has reiterated his intention to bring to light the still classified documents of the Dallas assassination. Why is Trump so insistent on revealing this black box, precisely now?

One of the leading researchers who has, over the decades, broken through the dense compartmentalization surrounding these documents is Peter Kornbluh, an analyst at the National Security Archives (NSA). So I asked him and this was his response:

As you know, nothing speaks as much about the Deep State as the conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Trump is a great believer in the Deep State, which, according to him, is after him. So, since his previous term, he ordered that some still classified documents be published. The CIA had spoken out on the matter, arguing that these documents contained a series of secrets, the disclosure of which could be damaging. Finally, Trump ordered the publication, and when it happened, one in particular turned out to be quite significant. It showed that the CIA had wiretaps within the government apparatus in Mexico, and in particular in the office of the president of the country. And that gives you an idea of the kind of secrets the CIA has been covering up for all these years. What is still being censored (in whole or in part) in these documents reveals the efforts of the CIA and those on its payroll who held very high-ranking positions in the Mexican government.

Now then, Trump does not really respect the issue of classified information. We already know this, from having secret documents and taking them to his Mar-a-Lago home after he was president for the first time. He often gives classified information to people he shouldn’t. And that’s why he wants to present himself now as a transparent president, willing to let all these documents come to light. Ley’s see what happens. There will surely be some interesting bits of history. But we’re certainly not going to learn anything more about who killed John F. Kennedy, beyond what we already know. In other words, it’s extremely unlikely that the declassification of these documents will change our understanding of the assassination itself.

I agree with Kornbluh that the declassification of documents surrounding the Dallas crime will hardly meet the existing expectations about the truth, nor open that black box with all its ramifications.

Indeed, no political thriller on Netflix has as many ingredients of drama and suspense as the assassination of JFK. At first glance, it is not difficult to imagine a conspiracy woven with the threads of his enmities, which within the United States alone were a legion. The hawks, who saw him as weak and guilty of the rise of “international communism”; the racists, who abhorred his sympathies towards civil rights and who were forced to put the brakes on integration in southern universities; the mafia, harassed by his brother, the Attorney General, who resisted “cashing up with them”; the CIA figures who saw their omnipotence curtailed after the Bay of Pigs fiasco; the military who had proposed taking advantage of the Missile Crisis to launch a first blow against the USSR; the most belligerent Cuban exile, who never forgave him for having abstained from intervening directly when the battle of the Bay of Pigs was seen to be lost, and who described the pact with Khrushchev as treason. Not to mention those in Vietnam, Nicaragua, Guatemala, the Dominican Republic, Thailand, Laos, the Congo, El Salvador, Ecuador, and elsewhere, who held the United States responsible for coups d’état and support for dictatorial regimes in their countries.

That, thanks to the declassifications ordered by Trump, all the hands behind the “smoking gun that pulled the trigger” become visible may be too naive.

However, as can be seen, reconstructing the historical context of the assassination right now is a very worthwhile exercise. Of course, to talk about what happened more than half a century ago, simple oral history is not enough, nor are speeches enough, nor are the feelings that that context makes us evoke now, especially if it’s about grasping it with its actions and reactions, instead of the sum of errors and successes.

I have focused on details of an interview published at the end of 1963, which barely thirty years later almost no one remembered — not even Fidel’s elephantine memory; as well as on his evocation of the 1962-63 situation, broadcast by Cuban Television another thirty-odd years ago, and which most people surely do not remember either. Finally, I have alluded to the meta-diplomatic dialogues and exchanges that appear in secret documents, sometimes declassified with many crossings out, that I have come across while going through presidential archives.

The most interesting thing about this reconstruction is that it allows us to put together pieces of a puzzle, where images of JFK and Fidel emerge, in that context so different from that of today; images also very far from the spirit of inflexibility and ideological doctrinarism with which they are often characterized.

There is JFK, who at 43 had been elected president of the United States; whose greatest defeat, the Bay of Pigs invasion, and greatest achievement, the solution to the Missile Crisis, were linked to Cuba. In 1963 he had already learned what the cost of overthrowing the Cuban Revolution by force could be. He remains concerned about the Cuban-Soviet alliance and the influence of the Revolution on national liberation movements in the region. But he knows that to influence the Cuban course, it is necessary to begin by discarding ultimatums. And he has begun to explore that path.

There is Fidel, who at 32 was the political leader of a national liberation revolution, opposed by the United States almost from the beginning; he is no longer a guerrilla in power, but a statesman, who has dealt with the two great powers amid the Missile Crisis. He seeks dialogue with the United States that has waged war on him with everything, and whose political complexities and idiosyncrasies he knows very well. He is willing to talk about any concern of mutual interest. Ready to negotiate on any issue of our international relations, although not on the system brought by the Revolution or national sovereignty. He is 37 years old and has a worldwide reputation.

Although history did not take the path that the will of both leaders indicated, taking advantage of that legacy would be worthwhile, in the context of Fidel Castro’s centenary.