In this same column, I have referred to my research note on the Military Units to Aid Production (UMAPs), published in 2015, and which has almost disappeared from the Internet. It consisted of a brief characterization of “the time of the UMAP”; and was based on almost twenty individual and group interviews, including recruits, guards, military chiefs, psychologists; numerous published memoirs, especially from religious figures; and some unpublished documents and speeches from the time.

In my opinion, the available texts on the UMAPs continue to lack an examination of the historical and political context of Cuba at that time, as well as documents that can serve as a critical historical review.

Instead of understanding them in their time, when homosexuals were misunderstood, discriminated against and repressed throughout the world, the UMAPs are credited to erase them from Cuban society, confining them indefinitely in concentration camps, from which they could not leave, in order to “annul individuals who were considered undesirable and excludable within the new concept of Nation.”

It is not surprising that stereotypes and anathema predominate and have made the UMAPs a cursed topic, like no other in more than half a century, a kind of flower that some cultivate with their own fertilizers.

A thorough investigation would naturally require access to ignored sources and testimonies, which would allow us to analyze what happened, its causes and context.

I have set out to return shortly to some ignored testimonies, but also revealing ones, such as those of guards and military chiefs that I interviewed; I contrast them with the detailed chronicles of evangelical pastors, in order to dedicate the time and characterization they deserve.

Speaking of primary sources, some original documents, supposedly extracted from anonymous archives, have recently been put into circulation on social media; among them, some that collect aspects of the work, established for the gay population in the UMAPs. I want to return specifically to that point here in order to shed light on the purpose of the work in the camps, based on the protagonists themselves.

To characterize the role of the team of young psychologists that was requested by the Revolutionary Armed Forces (FAR) to work in the UMAP contingent, I have returned to Beatriz Díaz, who was part of it. I interviewed her in 2015, as part of my research, and I have asked her to review and expand my questions, almost ten years later.

How can the UMAPs be explained? What factors from that time may have influenced the decision to create them?

At that time, there was a way of thinking that exalted physical work and conceived it as something that makes people develop. At the same time, it was used to punish, not only in the case of the cane cutting in Camagüey but also in Guanahacabibes, Pinar del Río, where the cadres who had made certain mistakes were sent.

It was the style of an era, where similar processes occur, although not as structured or as large, or as comprehensive as the UMAPs, but based on a prevailing idea that through physical work people could change, develop, become better.

What was the origin of the research work requested from the School of Psychology on the UMAPs? What was the objective?

At school we carried out work of a different nature, more sociological, such as the one directed by Dr. Aníbal Rodríguez in 1965, in nine sugar mills in the north of Oriente, which was the beginning of our participation in similar tasks, so that a large number of similar applications were submitted.

The first group of psychologists graduated in October 1966. I don’t remember when the research on the UMAPs began. It was always directed by María Elena Solé, who died in November 2013, a very dear friend of mine, and without a doubt the most qualified person to talk about that experience. I went there for some time to help, and then they sent me to do other jobs.

The reason was always to try to eliminate the UMAPs, starting with the population considered homosexual that was there. We went there to try to get those homosexuals to stop being there. That was the purpose of our work.

In that period of the 1960s, homosexuality appeared as a pathology in disease classification manuals, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Values of Mental Disorders (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association. Psychometric and personality tests also had questions and techniques to diagnose homosexuality, which was considered a mental disorder, a personality disorder.

The DSM has had different editions. In the second of these, the DSM II, published in 1968, the category Sexual Deviations appears and homosexuality is in first place on that list, together with fetishism, pedophilia, transvestism, exhibitionism, sadism, masochism.

However, we did not go there to diagnose homosexuals, but to determine who could reintegrate into common life in society and to release them as quickly as possible. That was what we set out to do there.

On what basis could it be decided or discriminated against that there were some who could be more easily integrated?

Through individual interviews we tried to determine to what extent that person had the possibility of rebuilding his life quickly, and of reintegrating in some way at his level, without any pre-established parameters.

Did you determine that someone from that sample you had, or from that population, could be quickly demobilized and others that had to stay?

There was a kind of classification, I don’t remember what the categories were, but to release them, so that they would leave, trying to get as many people out as possible.

Were most of those who were in the UMAPs gay, religious, or disaffected, or what?

We had no links with anyone other than the population considered homosexual. The group that Maria Elena led had nothing to do with the others that we know were there, religious and other people. As it was supposed to be a pathology, and the psychologists specialized in pathologies, they sent us there.

To what extent could psychologists contribute to reducing the tensions or levels of conflict that could exist; to coexistence? Was it part of the mission?

I didn’t witness it, but Maria Elena told me about the coexistence of the people who were there, in particular the prisoners and the soldiers. According to her, the mothers of the gays who were there brought them things that they liked: women’s underwear, makeup, etc. Because some of them put on artistic shows, and the audience was the guards. There came a time when they reached a coexistence because two such different human groups have to live together and reach a kind of mutual tolerance.

Did the presence of the team of psychologists somehow change the attitude that the guards in the prison had concerning gays?

I can’t answer that, I don’t know. But I do think that they realized what we were doing. They knew that it was to end that. Perhaps the person who could answer that question would be Captain Felipe Guerra Matos, who was like the boss during the period that we were there.

Were the interviewees sincere when they spoke with the psychologists?

If the individual you interview feels that you are not judging him, that you are on his side, because it is true, that has to be true, it is not a fake professional skill, it is a genuine feeling, that the person you are interviewing, regardless of whether you do not agree with his way of thinking, you are not judging him, but you are trying to communicate with him, to put yourself in his place. They knew that it was so that they would be released.

What was your impression of the officers, of the authorities, of the guards who were there, in relation to the task they had?

They were punished there as well. I think the military were punished. Some were punished formally, for having broken a certain rule. And the others were punished in fact, because of the isolation in those camps, that coexistence, for me was a punishment. Although of course there was an obvious asymmetry of power. The military, with the power; and the other, subjected to that power.

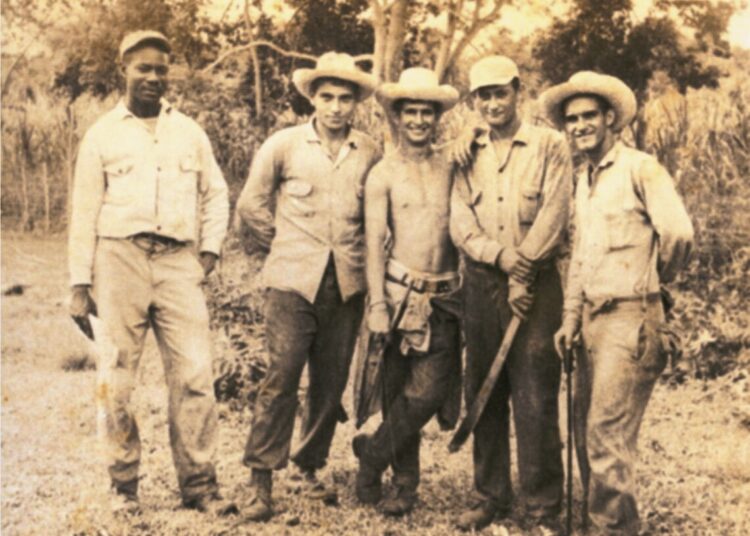

On the other hand, those soldiers who were there in the late 1960s were people with a very low level of education, from rural, farmer backgrounds, many of them with a rather conservative mentality, and who could not understand human diversity. They could be good people, because of their feelings. But they were narrow-minded. That was my experience with the military at that time.

On the other hand, it was a time of predominance of an equally exacerbated machismo, not only among them but in general.

However, the coexistence that was evident in those cultural events, whose audience was the military themselves, indicates a mutual tolerance, particularly towards those who were subjected, which comes about from forced coexistence, because, as we said before, both are suffering that punishment.

Was there in some way a relationship between the group of psychologists ― they were very young people who were there, recent graduates ― and those guards? What was your relationship like with the guards?

I remember Guerra Matos1, and Quintín Pino Machado2, who seemed to me to be a very interesting person, because of his way of thinking, and his broad-mindedness. And I knew Guerra for many more years.

Did the team of psychologists really fulfill their role, in the sense of helping to create a way for them to be demobilized?

I think so. It was something that we liked to do, and we were happy to be able to do.

That stay in the UMAPs, that participation in that work, even though it was brief, what did it bring you as a psychologist, in your field itself? Did you learn anything from it?

I reaffirmed the idea that I could establish, through the interview, communication with any person based on that principle that I explained before, that it is not a technique, it is not just a technique, it is a value, that the individual has to have.

On the other hand, it contributed in some way to the elimination of something that, at least we, the psychologists who were there, considered should not exist, and that those people should not be confined in those camps. And the satisfaction of helping people so helpless, as you can say, of doing good.

At that time was this something shared, something that was spoken of naturally?

I mentioned what the supposedly scientific criterion of homosexuality was at the time. But what I thought, based on other studies I had done, was that the individual was not responsible, it is not a choice. Regardless of the causes of homosexuality, the different etiologies, biological, psychological, etc., I thought about the process of constructing the self, which occurs in the first two years of life and is beyond the control of the individual, of his will. Therefore, we have to accept ourselves as we are. I have thought that since that distant time.

With the end of the UMAPs, discrimination against homosexuals or the discourse against homosexuals did not end; nor against religious believers.

Not at all. In the 1970s, when I collaborated with the Ministry of Education, I remember having seen documents where one of the reasons for the termination of teaching work was that.

In the same School of Psychology, some people could not enter because they were religious. And interviews were held and attempts were made to prevent them from entering. That was clear in the admission policies in the same School of Psychology where we were. There were guidelines not to let them in.

What do you think about the documents that have just been published on social media?

I know nothing about these documents, I have never seen them, so I cannot know their origin or evaluate their credibility. But there are three aspects that I would like to point out.

The first is related to the appearance of the name of María Elena Solé, as I said, a very dear friend of mine, but also admired and respected by many other people, because María Elena was the kindest, most honest and ethical human being I have ever known. In her many years as Director of the School and later Dean of the current Faculty of Psychology, in her practice as a clinical psychologist, in the care of her patients (for which she never received any payment), she always showed these principles in her conduct, hence the admiration, respect, and gratitude that the mention of her name evokes. That is why it is regrettable to see her mentioned again in these documents, more than ten years after her death when she can no longer answer or clarify anything.

Secondly, I would like to insist on the criterion of homosexuality as a personality disorder that prevailed in the 1960s. I mentioned earlier the DSM II, published, as I said, in 1968. The participation of psychologists from the then School of Psychology (converted into a faculty in 1977) in the UMAPs occurred in 1965-67, that is, almost sixty years ago. We, the graduates of the first batch of students (1962-1966), studied according to the DSM I, as did all psychiatrists and psychologists from the United States and other countries. Therefore, it is not possible to evaluate or judge facts from that time using current criteria.

Finally, I think it is appropriate and necessary to insist: the psychologists from the School of Psychology went to the UMAPs after a political decision was made: to close them. Hence the need to determine who could be reintegrated more quickly into society upon leaving there. And something significant for the time, the purpose of helping not only to release but also in some way to provide resources for their adaptation to a social environment that was known to be so adverse. I draw attention to the fact that there was no intention to “cure” this supposed pathology, as was common at the time when different psychotherapeutic and other procedures were used for this. Those who are interested in this can investigate the matter. That is, the purpose of the Cuban psychologists that María Elena Solé directed, to help with readaptation, is a manifestation of accepting these people as they are, without trying to change them or “cure” them, and can be considered a humanistic approach well ahead of its time.

________________________________________

- Quintín Pino Machado (1931-1986). Underground fighter in Las Villas. As a high-ranking Anti-Aircraft Defense of the Revolutionary Armed Forces (DAAFAR) officer, he intervened in the release of Pablo Milanés from the UMAPs, and was the first chief appointed to demobilize them.

- Felipe Guerra Matos (1927-2024). Captain of the Rebel Army. First president of the National Institute of Sports and Physical Education (INDER). Officer of the FAR, first chief of the Compulsory Military Service. He concluded the closure of the UMAPs.