The Felloves were an upper-class Cuban family, torn apart by the political conflict between the Batista dictatorship and Fidel Castro’s guerrillas. Until then, Cuba had been a little cup of gold. One of the offspring of the family, Fico, a musician and owner of a cabaret called El Trópico, kept out of politics. Don Federico, a university professor and patriarch of the clan, believes that the Cuban solution consists in going to elections and restoring the constitution of 1940. He has warned his son that they are in a position that in chess is called zugzwang; in which any movement costs. Double-edged, he tells him. “The best thing would be to not make a move.”

Meanwhile, however, two other sons are involved in the fight against Batista; one dies in the assault on the presidential palace, and the other goes up to the mountains with Che.

At the fall of the dictatorship, the revolutionary regime prohibited the use of the saxophone in orchestras, described as an imperialist instrument. Che personally informs the decision to Fico, who is leaving Cuba, since his cabaret is intervened, and his great love, the widow of his dead brother, has sided with the Revolution. In exile in New York, where he survives by washing dishes and playing the piano, Fico puts his life back together, founds a successful nightclub, and returns to his true homeland: the music that lives on there.

This is the plot of The Lost City (2005), directed and starring Andy García, with a script by Guillermo Cabrera Infante. Despite the endorsement and special performances by Dustin Hoffman (Meyer Lansky) and Bill Murray (Cabrera Infante), the film’s reception was, shall we say, problematic.

The prestigious Rotten Tomatoes critics gave it a 25% approval rating, adding: “What starts out as a promising exercise turns into a disappointment, overly long plotted, and unevenly directed.” The Boston Globe gave it “a penthouse look” on Cuba and the Revolution. The Los Angeles Times said that it was frustrating that the inordinate and reckless vision of its creators had become the biggest drawbacks and not the biggest benefits of the film. The NYT called it a failed romantic epic that runs across the screen for almost two and a half hours without saying much, other than that life was wonderful before Fidel Castro came to town and ruined everything.

Despite the film’s mediocrity, its “historical inaccuracies,” the fact that the dialogues between Don Federico and Fico are more like those of Michael and Vincenzo Corleone, and that the film is barely an exercise in nostalgia for that lost city wrapped in glamor and music, most reviews identify with the historical accuracy of the evocation. That is to say, with a representation of the Revolution as loss, sentimental annihilation, excesses and violence, disintegration of the family, disappearance of a “genuinely Cuban” culture and that made a clean slate with almost all of the above.

Initiating a debate on Last Thursday about the idealization of the past, more than eight years ago, it occurred to me to read these words by Walter Benjamin: “Articulating the past historically does not mean knowing it as it truly has been. It consists, rather, in taking possession of a memory as it shines at the moment of danger…. Danger threatens both the existence of the tradition and those who receive it. In each era, efforts must be made to wrest tradition back from the conformism that seeks to subdue it. The gift of igniting the spark of hope in the past is only given to the historian perfectly convinced that not even the dead will be safe if the enemy wins.”

Of course, Benjamin, one of those history philosophers who says a lot and very clearly, spoke of the real and concrete danger of Nazism, in 1940. That historical recovery was not then — and certainly not now — an academic matter, nor was it just the task of professional historians, but rather a social and cultural phenomenon. Because narratives about the past include others, such as literary, artistic, audiovisual, educational, media, political, and religious. All those discourses appropriate it in a certain way, and in doing so they often exalt the positive or negative traits. In other words, they idealize or demonize the past.

If one adds the idealization and the demonization, believing that they are the two halves of an orange, and that this is the path of truth, what one obtains is rather two empty eggshells, instead of a complete orange. But many pass this sum of opinions as “objectivity.”

A historian of the stature of Oscar Zanetti recalled that “memory is a selective mechanism and it goes hand in hand with forgetting. That is to say, in our conceptions we operate with a selection process, both on an individual scale and on a social scale, which obeys dissimilar circumstances and is conditioned by individual, social and group interests, and by factors that determine what and how is remembered.”

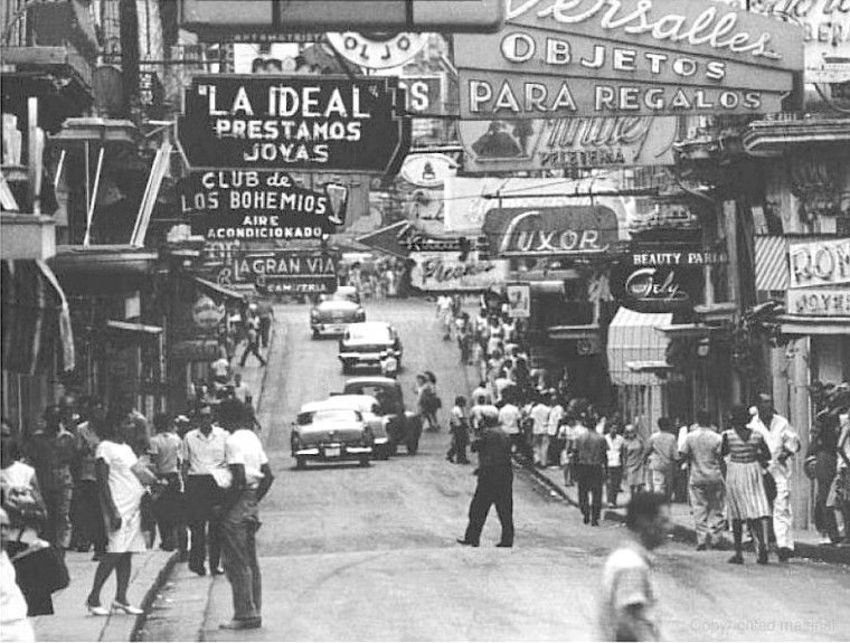

In that 2015 debate, Alfredo Prieto pointed out: “Outside the island, there is the so-called discourse of nostalgia, which offers a specific image of Cuba: we were practically the Switzerland of America. And a whole symbolic industry is generated about it. After the opening of the 1990s, these images began to penetrate people who have little knowledge of history.”

What factors affect the reconstruction of the past? What contemporary problems favor the idealization process? There’s plenty that could be said about it.

Speaking of a famous artist, someone pointed out years ago: “Before it was prohibited, and now it is mandatory.” However, official policies and discourses have long ceased to be the sole determining factors of the mainstream. Especially if we understand it as the substratum of daily conversations, and how far the axis of what is politically correct goes. Because each era brings with it a mainstream. It is obvious that the current one is another.

Indeed, this axis today depends more on social and cultural codes that have been gradually assumed, and that, as Zanetti said, respond to individual, social and group interests, which are increasingly frequent and visible, also reflected in what and how one remembers. In short, according to Benjamin, the past is invoked more to defend arguments and topics of the present than to dig into time.

None of this would be especially new or strange or haphazard if Cuban politics exhibited the subtlety and nuances that it had before. If it were not that we are barely aware of the contingencies that are occurring in the minds, much more than in public spaces; and not only as a result of the so-called culture war, but also sometimes with the collaboration of our own institutions.

It would not be risky, if it were not, as a filmmaker friend of mine says, that, at a moment like this, “a poorly called out at third base” could have exorbitant consequences. It is even more so because we believe in the effective power of ideological mobilizations; in the alarm calls to face the capitalism that is approaching when a new business is approved or a treaty with the European Union or Russia is signed; in the acts of repudiation against a social climber who makes merits of civility in the networks giving a piece of his mind to a State that has seen its former hegemony undermined. It would be enough, I say, to understand that the heterogeneous and contradictory condition of the current consensus has a social and cultural nature, and requires political eyeglasses that do not polarize those differences, nor read them as irreducible ideological colors.

Just as carrying out a political catharsis by passing the bill to the established powers releases tensions and lightens the atmosphere, writing about the past with another grammar makes sense. Dealing with that past, Benjamin would say, or rather with the ways of perceiving it, is more than reasonable. Hence the voices that, like Don Federico Fellove, would today prefer the Constitution of 1940; return to that country where no one got involved in politics, as Fico wanted; reconcile all of us as happened in those Cuban families that before 1959 were never divided or emigrated; return to that land of the Espejo of patience, full of tropical fruits, and fine foodstuffs and liquors, as a witty peasant I met used to say.

Without irony, it would be convenient to revisit the 1960s, to review them thoroughly instead of continuing to call them the prodigious decade. Just like the 1970s, when, in addition to the gray quinquennium, the greatest educational revolution in our history took place, and Cuba acquired all the international legitimacy with which it continues to fly today. Going back to the 1980s, when the highest levels of well-being were reached, and the deepest and most controversial cycle of citizen consultation to date was unleashed. And to reach the much misunderstood and forgotten Special Period in peacetime, a strategic-military jargon term, which encompassed the most intense intellectual outbreak and renewal of our political culture since the early 1960s, together with the last period of crisis spread from 1968-1970, more arduous than any.

What has been the socialist summer dream, for many the present has turned it into a nightmare from which they want to wake up. They see a return to some of these pasts as impossible, almost always disfigured by our own nostalgia. And they are not wrong. Many times they invoke other dreams, in which they replace the dystopian socialism we live in with Chinese, Vietnamese, and Scandinavian utopias. Learning lessons from those others is worth a lot, but probably not as much as from our mistakes, setbacks, conquests, struggles with ourselves.

Among the salvageable lessons of that tradition is, let’s say, that a citizen democracy is not built only with the best possible constitutions or the most advanced laws, nor with liberalizing business practices, as the experiences of some other socialisms also show. It is in the strict field of politics where the most radical and far-reaching transformations are played out.

To learn from our struggles, it would be worth remembering, let’s say, when Cuban artists and writers achieved, at the most committed moment of the Special Period, the recognition of labor autonomy that was later called self-employment, the freedom to travel and stay abroad for long periods, the ability to address the most thorny issues of society and politics in their narratives, plastic works, films, plays, choreographies; they were blazing a trail, charting a route to what society and politics would later achieve.

None of this was achieved with stridency and boasting, provocative poses or rhetoric, nor slamming fists on the table, but with a willingness to dialogue and perseverance, persistence and negotiation.

On this journey through the past, perhaps we will be able to reach the point of clarity necessary to stop blaming the Soviets for all our mistakes, dogmatism, laggings, extremism, ineptitude, nonsense (Raúl Castro dixit). Perhaps we can get out of the scholastic dilemma of the continuity of the Revolution or the date it ended, to extract the meaning of that tradition, and strip it of conservative atavisms, as Benjamin requested. Perhaps we can recover the essential heterodoxy, the audacity, the defiant bias of the thought and action of our great dead, their lucidity and political capacity to communicate and lead.

Let’s hope so.