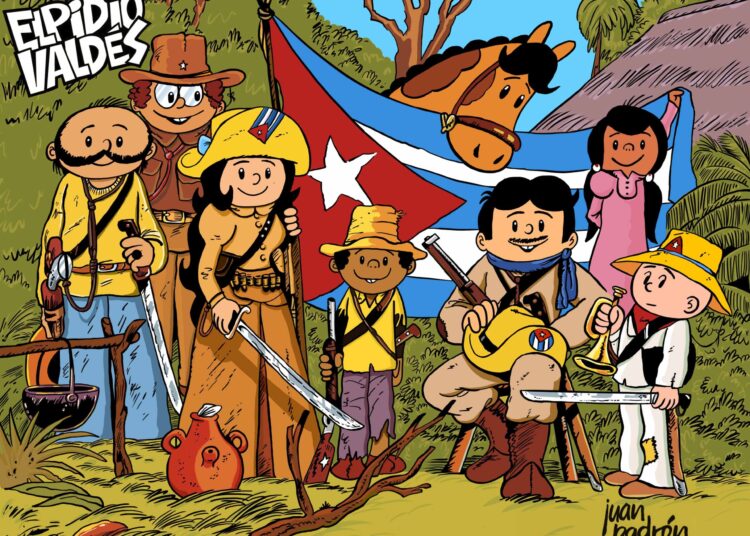

Few portraits of the island’s society compare to the comic strip of Elpidio Valdés and the film Vampiros en La Habana (Vampires in Havana). They bring together a diverse array of Cuban characters, situations, and ways of being; social hierarchies and characteristics align and clash, as radical conflicts are narrated. In these narratives, people of all ages and colors, born in Cuba and elsewhere, converge, divided more by their loyalties than by any other difference. They narrate a Cuban society in the making, through particularly turbulent and polarized processes, where what is often called the Cuban nation is built and rebuilt.

Although it may seem ridiculous to some, it would be good to remember that those who turn 60 in these months — and less — grew up reading those comic books, instead of Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, or Superman; as well as watching the films that, in the following twenty years, transformed them into popular culture for all ages.

Not for nothing has a film critic stated that “my generation’s imagination about our first wars of liberation took shape in those matinee movies where the laughter never ceased, rather than in those stern Cuban history manuals.”

That the history of the independence revolutions and the 1930s, available before and after 1959, is more entertaining in animated films than in the work of Cuban historians (Guerra, Portuondo, Ibarra, Tabares, Soto, Loyola, etc.) might not be so unusual, but rather logical, since no 300-page volume can compete with a series of cartoons.

In fact, it would be a slightly abusive comparison. If by “manuals” one refers only to textbooks commonly used in secondary education, it would be a critical judgment oft-repeated in debates about education and culture.

However, limiting the scope of Elpidio to its “patriotic-military” content, or classifying vampires as “soft ethnocentrism,” the kind that attempts to place us at the center of the world, does not do justice to the complexity of its plot. Nor does it reflect its role as a connecting vessel with the existing historiography on those two revolutions and their dramas, their adventures and their repercussions beyond the island, which have made it a living and active part of Cuban culture.

Associating these cartoons or that historiography with “Marxist orthodoxy” or with “the military solemnity regarding the evolution of the Cuban character” is a more than abusive generalization. It’s the same as describing Elpidio’s films as “a system of characters full of charisma — divided into two opposing sides (natives vs. foreigners, colonized vs. colonizers)”; or reducing “the main conflict” to “a clash between customs, habits and ways of thinking.”

One of the keys that explains why many Cubans of different faiths recognize themselves in that mirror is precisely that they don’t see themselves as idealized. And alongside them, other Cubans who are not as upright, cool, tough or even patriotic are also very visible.

This isn’t about the dichotomy of colonized vs. colonizers; much less about simple cultural contrasts or “ways of thinking.” Rather, it’s about a history of social struggles inseparable from national culture, which includes highly contradictory civic and political behaviors.

It would be necessary to start by accepting, let’s say, that national culture includes our alienations. As the Abakuá philosopher Tato Quiñones used to say, for example, racism. As well as the colonial mentality — we might add — the adoration of all things American, even to the point of annexationism; or the contempt for rural people (“Palestinians,” they call them, as if they lacked the right to a part of their territory); or for those who share neighborhoods labeled as marginal (as if they were nests of criminals and not breeding grounds for popular culture, traditions, music, dance, and the faiths of the people); or for gays and people with disabilities, and so on.

The notion and term “national culture” are not a spell that ignores its negative expressions: bureaucratic hypertrophy, abuse of power and administrative corruption, political and religious sectarianism, nepotism, some as old as the colonial legacy.

It’s clear that the good of some is not and has not always been the good of all. If this were the case, the Cuban Mambí independence fighters would not have been fighting the Cuban collaborators of the colonial power; the Cuban revolutionaries of the 1930s would not have fought fiercely against the Machado “porra” (secret police), the other henchmen of the regime and foreign interests.

There are those “rayadillos”, mercenaries in the service of the Spanish crown; the counter-guerrilla Captain Media Cara, brutal and bloodthirsty; the foremen in the service of Mr. Chains, the U.S. landowner, as well as the Sheriff and the NYPD officers; Captain Vives, Machado’s chief of police, and his collaborators, informers and repressive police officers.

However, what distinguishes these “cartoons” is not the revelation that among us, as part of that Cuban nation of which we tend to pride ourselves, there are creatures worthy of being represented in one of the circles of hell that Dante imagined for his compatriots. And whose interests would be inconceivable in a free and sovereign republic that could be called “for the good of all.”

The most important thing, however, is not to draw the line of demarcation for those who have never been and cannot be within it, but rather to oppose it in a bad way, and based on irreconcilable interests. The important thing is to define the latitude of what is ours.

I only want to note here two dimensions of the Cuban situation and its struggles, very visible in these animated cartoons, which are key to understanding that latitude: its diversity and the international nature of our problems.

The battles against the colonial power and its allies are not only fought within Cuba, but also in the United States. In the Elpidio saga, New York and Tampa are also battlefields; and multiple actors converge there.

Similarly, the cause of independence includes not only the insurgent forces, Cubans from very different social classes, but also numerous non-Cubans. If this cause represents the entire nation, the struggle that paves the way for it is an open road, unhindered by citizenship.

Also subject to this struggle are Puerto Ricans, Mexicans, Colombians, Jamaicans and Americans. And first and foremost, Cuban emigrants, represented by the cigar makers, who contribute not only with money but with their imagination, inventing fantastic weapons, like the smoke from their cigars.

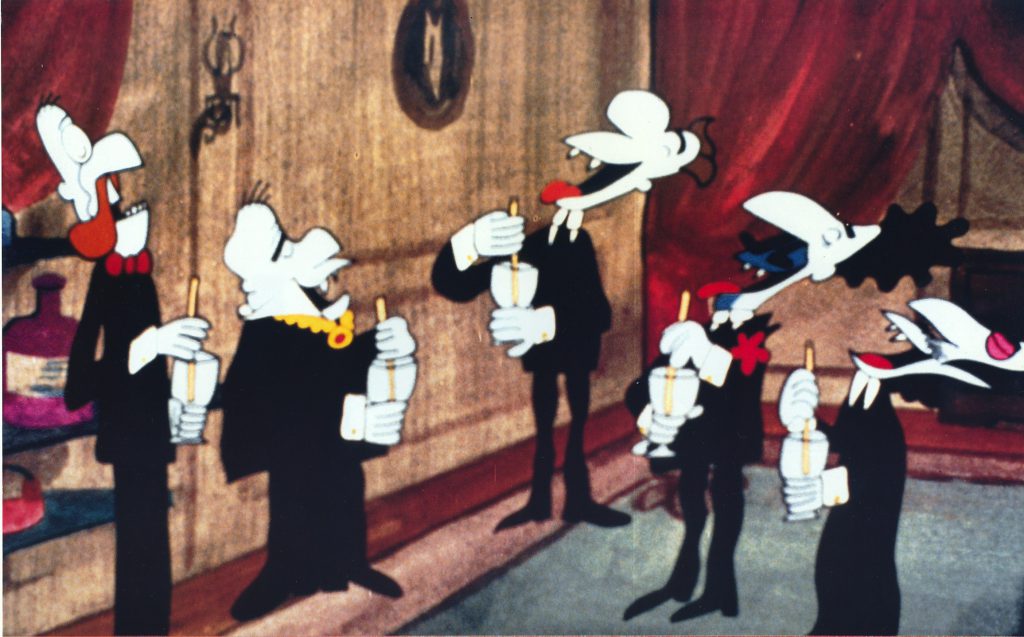

One can be a “Cuban Cuban,” a revolutionary combatant and a vampire. Indeed, the story’s hero, Pepe, is a member of an anti-Machado direct action group (as it was then called), as naturally as he plays the trumpet, and although he doesn’t know it, he is the grandson of Dracula.

Fighting simultaneously with police henchmen and the vampire mafias from the United States and Europe to steal the drug called Vampisol is a natural fit, as it is not an idle ethnocentric reflex. In fact, it is unclear who is more hellish: the European and U.S. vampire mafia trying to seize the formula, or Machado’s police and their henchmen, who are pursuing the revolutionary group.

In this revolutionary action, people from the bottom up — Black people from the barrio, university students, intellectuals and musicians — converge, seeking to overthrow the dictatorship, and they end up, without realizing it, facing enormous threats originating beyond.

The revolution overthrows Machado’s dictatorship, and the police chief ends up in prison; Cubans seize the universal “medicine” from the vampire mafias and donate it to the world in a radio broadcast. Because their struggle is not just gunfire, but imagination: the formula for Vampisol, reduced to ashes, survives in the lyrics of a son.

I don’t have room here for other topics that deserve further reflection. Let’s say, the Cuban sense of humor as a weapon of combat and a lifeline, which goes beyond the old and hackneyed issue of joking; or the significance of women’s role, both in roles like that of Captain María Silvia, and in their contribution to realism and resistance, prevailing over the improvisation of men and the rationality of foreigners. Not to mention rethinking our history and way of being, beyond the borders of the island condemned to “the cursed circumstance of water everywhere,” in its interaction with the big stages.

Not surprisingly, the second part of Vampiros… begins with Stalin sending KGB agents to Havana to monitor what the Nazis are doing regarding the Vampisol, while Hitler and Mussolini do the same. The fact that these themes are evoked in the tone of a parody does not diminish their significance as a geopolitical key to who we are.

Ultimately, with all and for the good of all, has too many underlying issues to attempt to resolve in one fell swoop around these animated cartoons. I also have a lot of questions about what Martí meant in that speech at the Tampa Lyceum, which he visited for the first time, and which will remain etched in Cuban cultural and political memory forever.

I asked them all to someone who has dedicated his life to understanding him, not precisely as a poet, but as a politician; who has helped dispel the mists arising from those Martí phrases taken out of context, and the very meaning of his political action, which continues to speak to us today.

I promise I’ll share them here very soon.