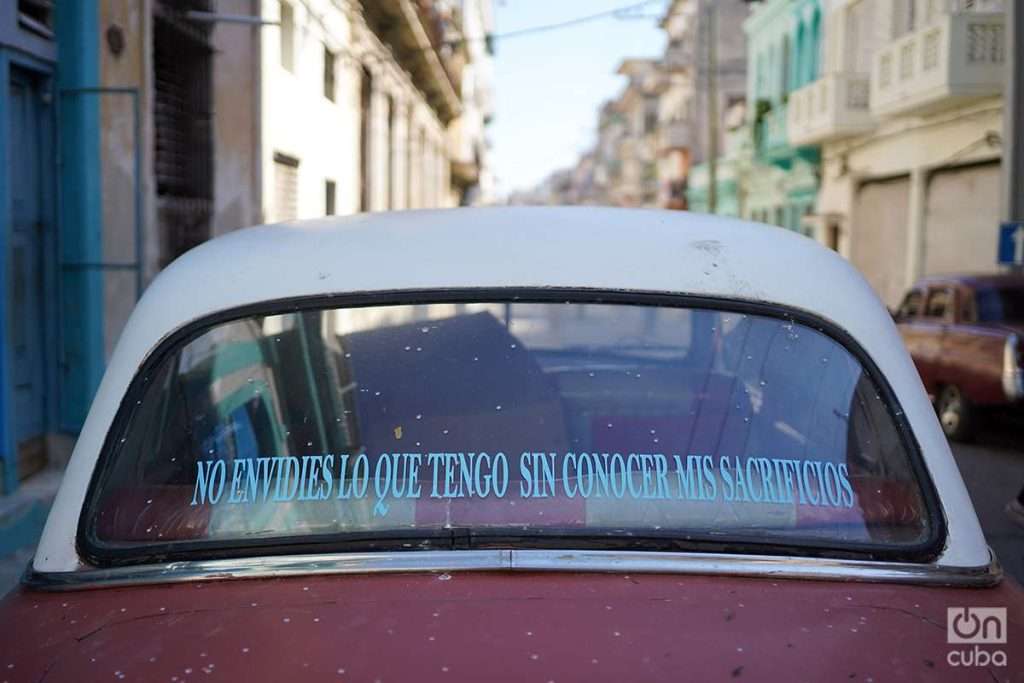

“Do not envy what I have if you don’t know about my sacrifices.” I read it recently in the back of a dilapidated almendron (American cars from the 1950s), stranded in the middle of the Havana neighborhood of Cayo Hueso and to which there is little to envy. It will possibly never roll again through the museum city that Havana is.

It is an established fact that the almendrones have been part of the island’s landscape for a long time, since they arrived without knowing that it would be “forever” and share a space with the Russian Ladas and Moskviches, others that refuse to disappear from our streets and that survive thanks to the expertise of our mechanics and the smuggling of parts from some select “mayamera” stores.

Between the distribution system that prevailed until the end of the 1990s, on the one hand, in which only vanguard workers or sycophants of the hour could buy a car, and on the other, today’s extremely high prices, not even remotely payable for the immense majority, when a Cuban is able to buy a car, it has to last a lifetime. Until death do you part and beyond, as it will be inherited from generation to generation per saecula saeculorum.

Cubans are inventive, no one doubts it. We are the kings of patching, recycling and the eternal life of our old cars; so much so that they have become an iconic image of Havana that is sold on postcards and tourist magazines.

I am an admirer of our mechanics, capable of modifying — and even improving — the designs of the most famous trademarks on the market. I like to take pictures of under the cars, working magic. The image of the devoured man, crushed by the machine that cannot live without him.

But the photo of the tourist almendrón and Havana in the background bores me. That’s why these photos go the other way, for that of the forgotten. The cars that, for one reason or another, have been out in the open for years, each day rustier and more consumed by time, with rotten tires and destroyed seats. Those that increasingly have the resurrection that takes them back to the streets more and more distant and remain under the sun and the rain as silent monuments to survival or decadence.

During my walks looking for them to take pictures of them, I found everything. Some Lada, few modern cars and many almendrones. Some abandoned any which way, others secured like a bank safe.

Although the prize goes to a blue one, the most destroyed of the ones I’ve seen, with an indecipherable trademark, crushed as if it were the only victim of a transformer battle. It was crushed by a building that collapsed when Hurricane Ian passed. The most surprising thing was not the state of the jalopy, but that its owner had put it up for sale, according to what some neighbors told me who even offered to call him if I dared to buy it.

But no. Neither my pocket nor my faith in the neighborhood mechanics are enough for such madness. Although it is likely that someone will buy it and in a couple of years, working Cuban magic, the blue jumble will roll down the boardwalk full of tourists, oblivious to its incredible history while taking their selfies.