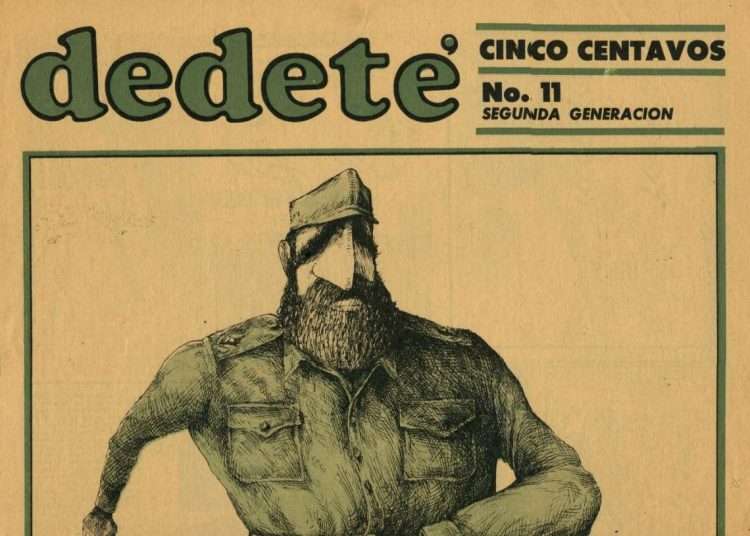

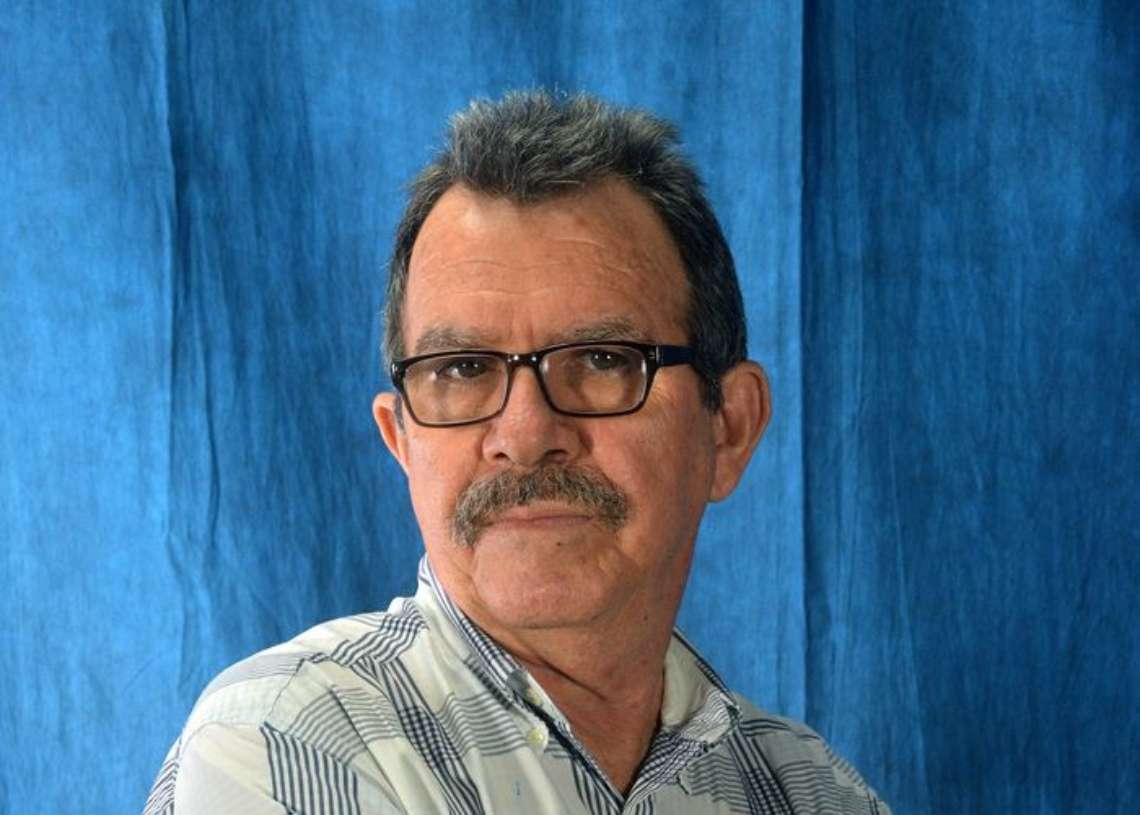

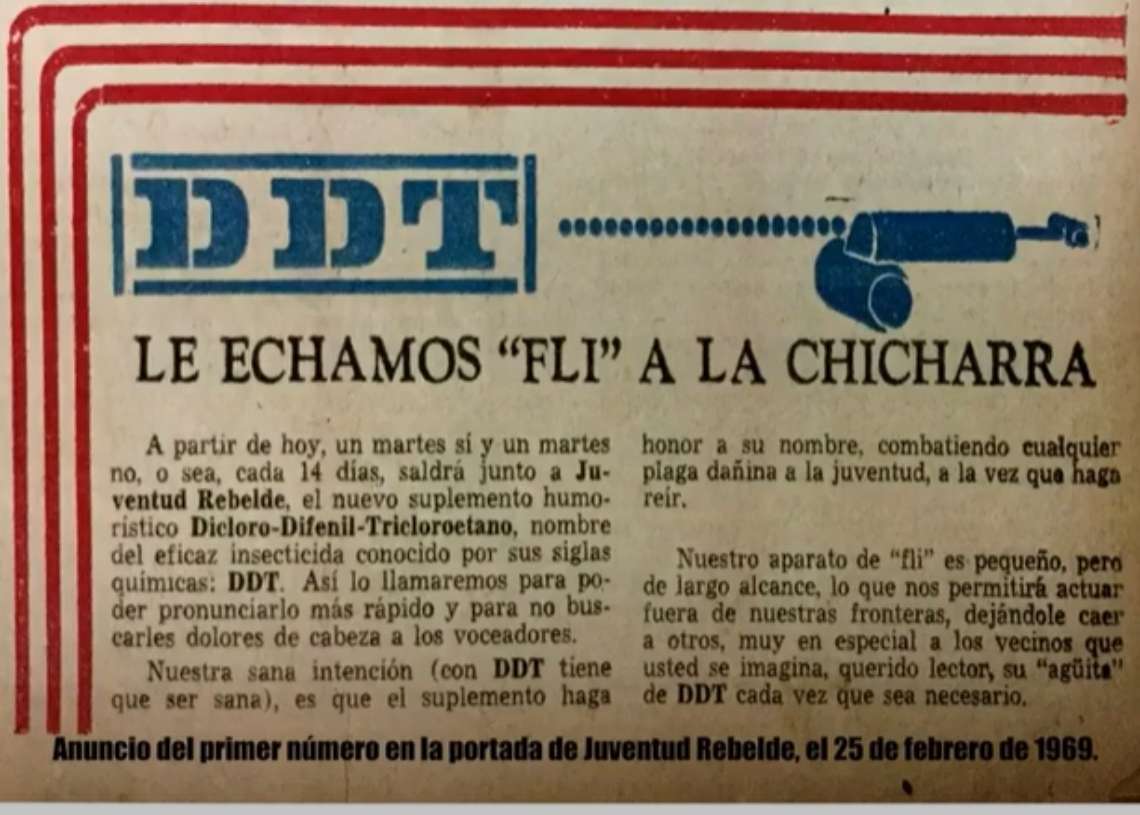

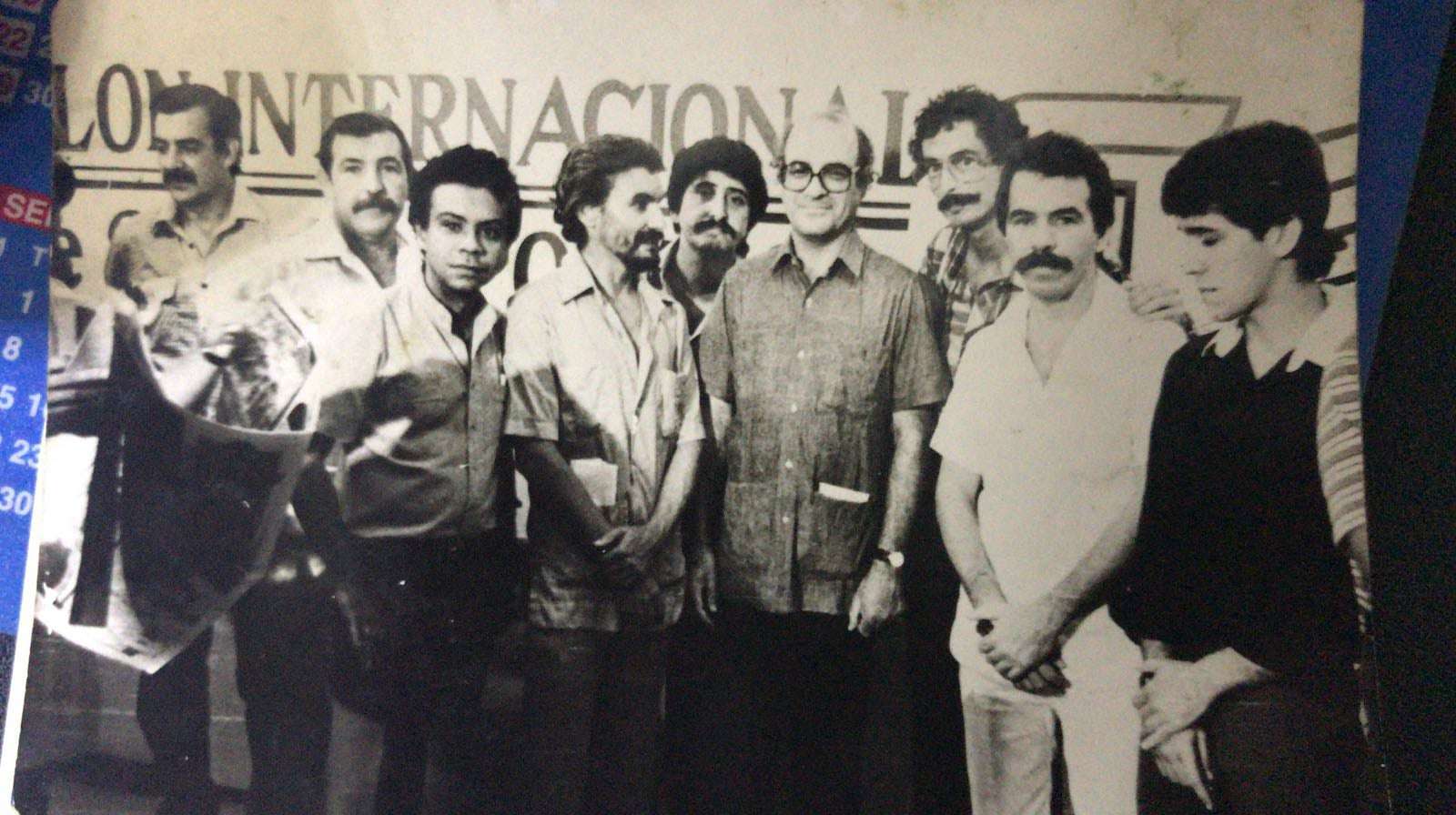

Wilfredo Torres (Havana, 1950), before being the ceramist he has become over the years, was in charge, between 1971 and 1991, of the art direction of Dedeté (DDT), undoubtedly the best Cuban satirical publication of all times. Pound for pound, as they say in boxing slang, the team of artists that met there in its moment of splendor had no rival in the country. I venture not even beyond.

By the time I worked as a journalist at Juventud Rebelde, I regularly visited the Dedeté newsroom, or what must have been the newsroom, since there was nothing conventional there. Next to a pair of Manuel’s socks drying on the back of a chair, you could find a splendid drawing of Carlucho. They lived there, joked at all times and with the greatest intensity.

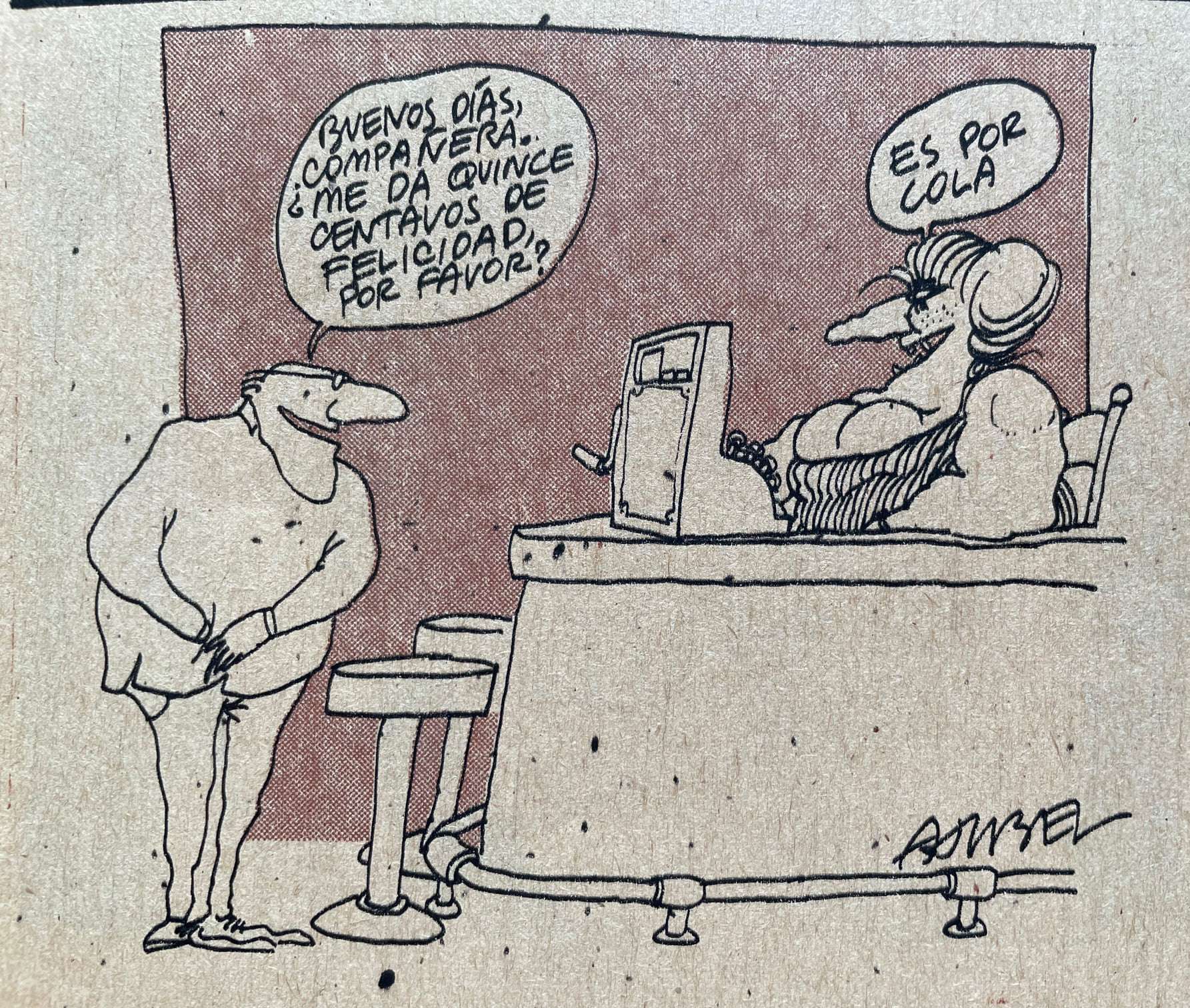

I had never known a collective that got down to work so joyfully. I would never meet one like it again. It was a Renaissance workshop. At any hour of the day or night, there was someone drawing splendors: I don’t know if the critics have already noticed it, but one of the things that dazzled me the most was that many of the drawings that were produced there — I’m thinking of Manuel, Ajubel, Carlucho — could have been hung immediately in a gallery or museum since they lacked the provisional nature, nervous urgency, that journalism imposes. I don’t think those artists tried to pose as virtuosos. They simply could not be otherwise.

About Dedeté I liked, above all, the human warmth that its members gave off, their noble mischief, the optimism with which they lived precariousness, their quality of being, smiling and hungry, in the here and now of that time, the overflowing lucidity and…their ability to get girlfriends. What more could a young editor want? Somewhere in the office, they had hung a sign that read: “Do not enter unless required. Avoid being employed.” And I was dying to be required, I was dying to be employed. But I didn’t get it.

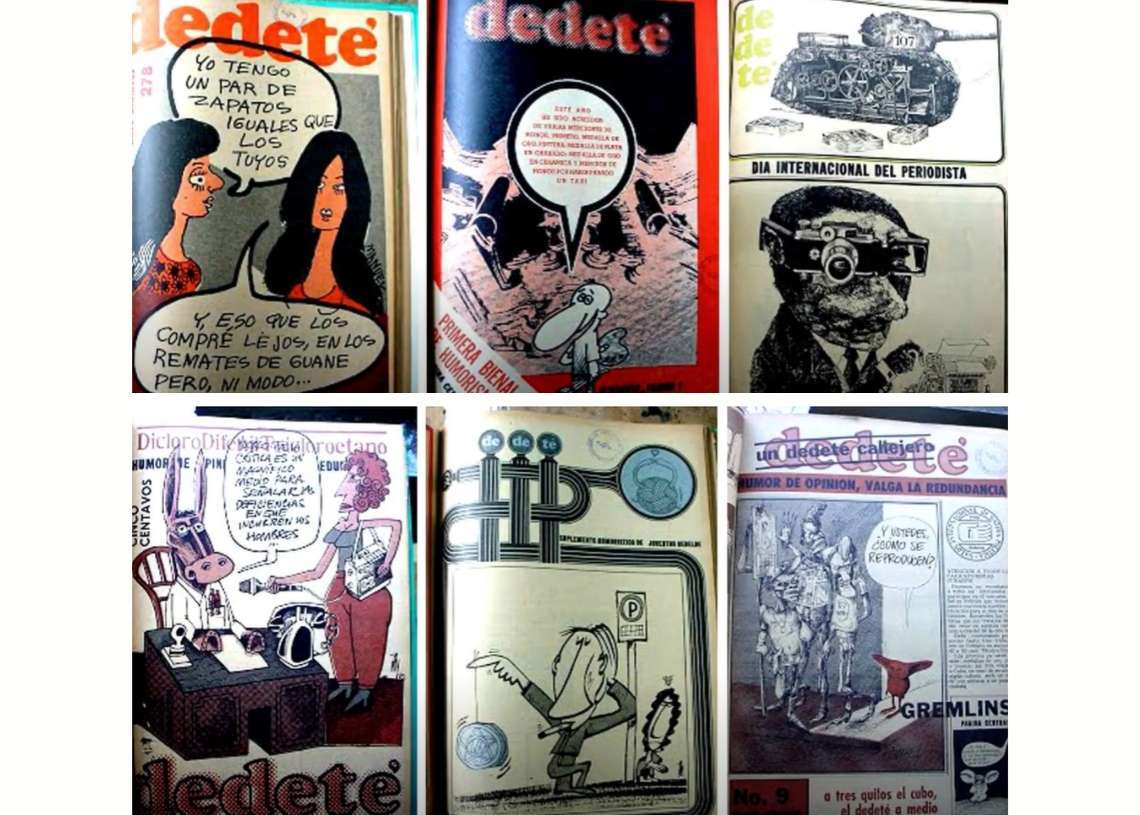

So much water has gone under the bridge since then. The publication virtually disappeared. It remains as a glorious reference to a peak moment of graphic journalism in the country. Moth-eaten issues of Dedeté can still be found in newspaper archives. Every time less. Let’s hope that heritage can be saved.

When Dedeté stopped coming out, Torres had to reinvent himself. Today he has a renowned work as a ceramic artist, exhibited in a dozen countries, and he continues to dream of “starting up again” humorous publications. Sátira Opinión (2017-2019) and Dos bufones (2019-2021) are his most recent attempts. In some future editions of this section, I will address his artistic work with clay. Now we focus on those two vertiginous decades in the art direction of the publication.

For twenty years you were the art director of Dedeté (DDT), which at that time brought together a group of stars. I remember the publication was located in rather dilapidated premises in a building on Teniente Rey Street. How did you get to DDT? What were those early years like?

Before beginning to answer your questionnaire, I must clarify that my story is personal and, as such, there are many gaps in these answers since it would be an immense job to write the history of this publication, the best humor published in Cuba in the post-revolutionary period.

I got at DDT in 1971, although I had joined the Juventud Rebelde (JR) newspaper a year earlier. I had come out of the Compulsory Military Service (SMO), and was on probation for twelve months, without salary.

That period was very valuable for me since I went through all the art departments of the newspaper. I understood how it worked, I learned a lot about typography, etc. It was my university, in essence.

I had worked during my stint in Military Service in technical drawing and that practice had given me a fundamental basis for my later development. I come from a family of publicists and architects, and somehow, I always knew that my final destination was going to be graphics. I loved tabloid design, and in fact, followed the world of editorial cartooning since I was a child.

During that probationary year at JR, I was able to develop many graphic design and illustration skills. I remember that almost at the end, Virgilio Martínez, the artistic director of the DDT, came up to me along with Agustín Urra, its editorial director, and they suggested I join as a director. It was really exciting to start working with artists that I admired so much.

At that time, the DDT was made up of Virgilio Martínez, Agustín Urra, and the cartoonists Juan Padrón, César Janer, Tomy, Manuel, Carlucho, a colorist, two editors: Ilse Bulit and José Raúl Capote, and me as a director. Its fundamental collaborators were Hernán H, with his Gugulandia, and Lázaro Fernández, an artist with a magical line and very interesting ideas.

It would be good to explain how DDT worked in those early years of life. It was a completely different publication from what it was later. From my point of view, it was very anchored in obsolete clichés, and the conceptual graphic solutions were not in line with the group of young people that made up the base of the team. I’m talking about Padroncito, Tomy, Manuel and Carlucho.

But the vicissitudes of fate intervened, and with a stroke of the pen all the people who did not fit into what would become the publication left DDT.

Literally, we were left with the aforementioned cartoonists and me, as the director. At that moment it was decided that Tomy would provisionally take charge of the direction, and that was the essential initial jump to what several years later would be the publication. The creative floodgates were opened from all angles, creating a feverish artistic atmosphere. A short time later, Padroncito also left, and the definitive nucleus that formed the publication for the next 20 years was left.

I must emphasize that those of us who made up that basic nucleus were empirical, and we grew by force of work. We all came from the Compulsory Military Service, and we knew the possibility and opportunity that we had in our hands. I remember that at that time we said that we were the owners of a publication that printed 250,000 copies every fortnight and that, due to those strange things of fate, and although many do not believe it, no one clipped our wings at that time.

The conflicts would come sometime later. We started and nobody put a brake. You have to give Tomy the recognition of that leap. He was the one who saw the future DDT and began to develop it.

During that time, the supplement was located on the 5th floor of the newspaper building, on Prado and Teniente Rey streets, in a place we called La Pecera, surrounded by glass, and with really great air conditioning. We had a table tennis table and chess boards. We almost lived there. It was a lot of fun and helped a lot to shape a collective spirit. In fact, Manuel and Tony slept on two sofas that we had between the drawing tables, since they did not have a home in Havana. My experiences of those times and the memories are so pleasant that every day I think about my colleagues and remember a lot of what happened there.

But not everything was rosy, nor was that the only place through which the DDT transited.

A short time later, the editor-in-chief of the newspaper evicted us from the fifth floor and we found ourselves in a small room on the third floor of the publication, where the workshops were. We gave this place the nickname of The Yellow Submarine. It was only for a few months, terrible though. Making each edition was an ordeal. The team scattered, almost on the verge of disappearing. But luckily, they got us out of there and sent us to what became the best possible location for a humorous publication. It was located on Teniente Rey between Zulueta and San José, next to that famous hotel that advertised itself as having 100 rooms with bathrooms. There we were free again and we began to recover and rebuild what we had lost a short time before as a publication.

That place was the one that definitively confirmed the identity of the supplement. It is then that Ajubel enters the publication, and the team rounds off its creative capacity and strengthens its graphic-humorous profile. That’s where the real DDT was born. That’s where the myth started.

René García and Ardión also arrive as members of the team, thus completing a team of excellent artists.

DDT at that point began to get bolder, and as a cultural project it had its ups and downs, but all we were doing was looking for our true identity. Large murals were painted in the office, which became littered with graffiti; it was an inclusive space, and many personalities began to visit us and hold gatherings there. Students, people from the street, came in to sniff and laugh. Seeing caricaturists draw without taboos broke down many barriers between ourselves and helped us loosen the few ties we had left with the handicapped mentally, as the Galician Posada would say. Years later we were transferred to JR again; and, finally, to the Combinado de Periódicos Granma, where in 1992 DDT was eliminated as a publication and became the last page of the newspaper.

There have been multiple attempts to revive the publication by a group of excellent artists, but my perception is that it is no longer possible. Everything has changed, and those great cartoonists, whom I respect, inherited more of a problem than a tradition. The DDT at its end already had many detractors at the political level who achieved their purpose: to make it disappear and to disperse the team.

I mentioned to you the DDT dream team. I would like you to characterize each of these artists, for me the vanguard of the collective, and tell me what you think their individual contribution to the publication was: Manuel, Carlucho, Tomy and Ajubel.

It was a luxury to have four artists of this quality in the supplement. Each one with a perception and style of touching on different topics. Incredibly, everything clicked. It was never difficult to make an edit. There was plenty quality material.

Manuel was the genius of DDT. I couldn’t say otherwise. He had the talent to demystify topics that were taboo in the Cuban press at the time. He paved the way for all who have come after. He introduced, at least in Cuba, the use of world-historical facts to criticize national problems. Genius of shapes and contrasts. His particular line gave him an indisputable grace, but at the same time, it provoked the desired reaction in the reader to the seriousness of the subject. A humble and tireless guy, aware of his great talent, but without the need to show it off. Always ready to work with the collective. My admiration and appreciation for him.

Carlucho was a genius of the so-called white humor. He had the ability to make a joke from different perspectives, without losing its grace and its graphic value. The lack of supporting texts for the joke forced him to develop spectacular compositions. A master of space. Watching him draw on gigantic scales was like taking drawing and composition classes. His sense of life gave him the power to touch on subjects that were forbidden to other cartoonists. He was an essential balance in the development of DDT. His training and improvement as an artist occurred already working on the publication. His development was dizzying, and his personality made him somewhat mysterious. He did not draw in the publication. He did his works at home and brought them to the newsroom. Always punctual and with supreme quality. He was essential for DDT.

When I met Tomy, in 1970, he was already an established artist, despite his youth. In addition to his graphic skills, he was a great organizer. I believe that, together with Virgilio Martínez, he was one of the people with the most technological knowledge of how a publication works. His drawings looked like architectural works, and his particular line totally matched his personality. Obsessive with perfection, he always worked until the last minute on his work. From him, I learned to work the films in the final layout of the DDT to enrich the number in progress. His frank personality, but serious and given to saying his criteria, brought us both several discussions. He was that demanding. Today I am grateful to have been able to work with him. He was Jiminy Cricket. A funny and serious guy. Demanding, that’s how this other DDT genius was, who died at the wrong time. I miss him every time I have to find a solution to my graphics problems. Rest in peace, my brother.

Ajubel came to DDT in the mid to late 1970s. He came from Melaíto, a humorous publication in Santa Clara. His drawing was already excellent and contained great humor. Refreshing and carefree. In the DDT he acquired the universality that his work lacked. His anthological cartoons, full of philosophy and subliminal messages, quickly revealed his great quality. Also, he fed the essence of the publication quickly. He is another essential genius to understand the role and value of the Dedeté of those years. His controversial personality and work made him an artist to be respected. His drawing went from one stage to another in the blink of an eye. Defender of the supplement at all costs, he has my admiration and that of all readers.

Ninety-nine percent of the magazine’s covers during that stage were distributed among these big four creators. Each cover defined the profile of that edition. Hence the variety in design. It was always very comfortable working with all of them.

When I began to design the number that would go to print, we had a world of fun and most of the time the best ideas came from there.

It was evident that you had a lot of fun making the publication.

Of course. DDT became a paradise for all of us. Each issue was made under a festive atmosphere. Of course, within the joking around there was an inviolable principle: to guarantee the quality of each delivery.

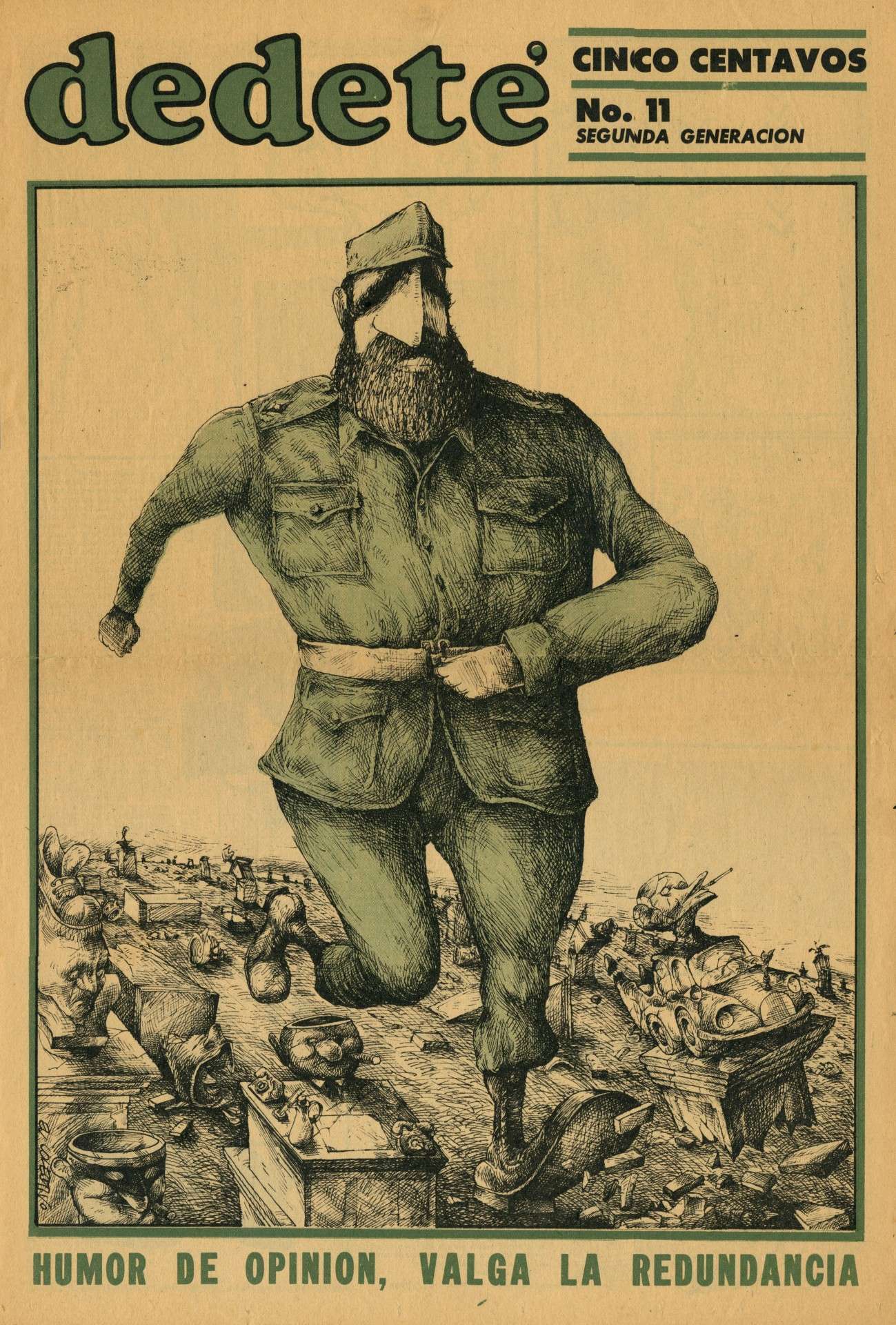

Work was sacred to us, and so it was in good times and hard times. Carrying out the publication in an artisanal and face-to-face way became a festive act. Today, with the use of the Internet, publications have lost that part of the freshness that gives everyone permanence at all times. That attitude also conferred a share of responsibility on all of us equally. There is an anecdote about when Ajubel made the cover with the caricature of Fidel, and together we decided to sign it as “El Colectivo.”

Today I wake up, already a few years older, and I think how happy I would be if I could go back to work in DDT with my colleagues.

I think those of us in that team who still live think the same way. They are the best moments I have spent in the company of such a talented group of friends, different and united at the same time. Working with them was a luxury that life gave me.

Cover signed by “El Colectivo.”

We know that politicians generally don’t have a very good sense of humor. Can you remember for us any edition that has been particularly controversial? Did DDT ever stop coming out because of censorship?

At a high-ranking meeting of the Cuban political class in the 1970s, someone said that DDT seemed to be made in Miami. It reached our ears through the director of Juventud Rebelde, who participated in that meeting.

In particular, I no longer support any political party or ideologies, dogmas or religion. I’ve become a little acid regarding that. In all societies there is censorship, and if we talk about humor, much more. Total freedom of expression is a fallacy. An issuer of ideas always has someone higher up who decides what goes and what doesn’t. That is not in dispute.

There were many editions of the DDT that were conflicting. Problems with ministries, ministers, politicians…. It was a daily occurrence and several numbers were censored and burned.

I remember an issue that we dedicated to gastronomy in Havana, and it consisted of a wake. The wake and burial of Inocente Blandito Conforme. That was the name of the deceased, who represented the death of gastronomy in the capital. We built a funeral chapel, a coffin and decorated the premises with chairs, just like a real funeral home. Osmani Simanca was introduced into the coffin and photos were taken and caricatures made. The cover was a full-page photo of the wake, with a text that strengthened the idea and mentioned the name of the deceased. Everything was going wonderfully, but the day the edition came out, Agostino Neto, president of Angola, died. That was the sentence of that issue of the DDT. The relationship that could be established between one dead person and another was very evident.

When Ajubel’s caricature of Fidel appeared on the cover, everything went well until it reached “above.” It only circulated in some parts of Havana. The rest of the edition was incinerated. That case was scandalous for us, but luckily it didn’t go beyond that.

In one edition, Manuel and I put a caption on an image that subliminally alluded to a character. The issue came out and after a while the director of Juventud Rebelde called us and Carlucho, as director at that time. We met and he informed us that we had two options: face a lawsuit because of that caption in the photo, with legal consequences, or burn the entire edition and between the three of us pay for the print run in full. That included layout, printing, shipping, etc. I don’t remember the total amount anymore, but that was the option we chose. The three of us had been paying for that prank for more than two years. But we really had a laugh and those risks are part of the job of a publication.

I would like to argue my opinion that the closure of the DDT as a publication was a vendetta. We were already doomed, and the Special Period was used to shut us down. Palante continued with an edition with less circulation, it is true, but it did not disappear. Melaíto continued coming out in Villa Clara…

Who to blame? The authorities of the newspaper, who did nothing to defend the publication. On the other hand, my sense of smell leads me to Carlos Aldana. It was an abuse to disintegrate a team of artists that had won the admiration of readers, with a large number of international and national awards obtained by its members, including the prize awarded in 1985 to DDT as the best publication of its kind in the world. Award given in Forte Dei Marmi, Italy.

What was the most difficult thing about doing humor in Cuba at the time?

It is always difficult to make humor, and it was not only difficult in the Cuba of those years. Making caricatures alone has a commitment, but when it is inserted into a publication, this commitment increases. In those years, making humor was complex, but we had gained a lot of experience and we overcame an infinite number of problems. I think that sometimes we were brave, and in others, luck had an influence. There have always been censors and red priests (so said Samuel Feijóo). We also had people who defended us, and that was very important. Today most of the editions of the 1970s and 1980s would be seditious. The same would happen with the ICAIC Newscasts that were dedicated to the DDT. By the way, ICAIC made a documentary on DDT that was never shown. We didn’t even see the final edit. What happened? I don’t know. It’s a bad memory.

We never asked permission to touch on a subject, but, of course, we knew we had to be serious, and we handled ourselves with that criteria. We learned to review the edition before the final printout, and in this way many things were able to happen. A publication has many rough aspects, and knowing how to exploit them became a weapon to avoid censorship.

They withdrew many things from us (they were for that) and approved others (those that interested us). It wasn’t always like that, of course, and it cost us tremendous rows. Those were incredible times, and today I am still amazed at the many things we were able to do. Dedeté did several unique things for a humor publication of its kind. One was when we signed the famous caricature of Fidel made by Ajubel as “El Colectivo.” The signature was as strong as the caricature. It was a cry of protest against censorship and in favor of the freedom to publish compromised humor. The author was also protected, of course, but I think it was a very brave attitude from the whole team. I have not seen any other publication in the world that has done something like this. Remembering today is fun, but they were actions that were very committed to our work.

Caricaturists in Cuba are in worse conditions than us, although I must say that I know of the high quality they have.

How did you start in ceramics?

I started in the world of ceramics as a hobby.

At the end of the DDT, I ended up as chief designer of Juventud Rebelde, but that was torture for me. It was precisely then that I found ceramics. In those early days of working on my new expression, Leonardo Padura and Lucía López Coll, his wife, visited me weekly. They arrived on their Chinese bicycles and made a stop to drink water, coffee, and smoke a cigarette. There we laughed at my pieces. I remember Padura saying that my vases did not look like vases or ashtrays. That they made no sense.

Luckily, I had friends who helped me during those early days. Oscar Cepero and Fúster were my mentors, and I will always thank them for what I learned. For a while, I was not well. The DDT shutdown made me depressed, and I didn’t know what to do; I felt terrible. I started building my ceramics workshop and was able to make my first kiln. The one who gave me the click of the path to follow was Salvador González, engraver, painter and designer; he was the one who told me that I should transfer my concept of graphics-humor to ceramics, and from there I began to unravel my life.

Converting two-dimensional concepts and perceptions to three-dimensional ones was an arduous and difficult task.

I remember that Alejandro Alonso, director of the Museum of Ceramics in Cuba, now deceased, invited me to exhibit some work at the Castillo de la Real Fuerza, in the city of Havana, during a Plastic Arts Biennial, and it happened that a Dominican gallery owner invited me and Fuster to exhibit in Santo Domingo. I even remember the name of the exhibition, Guajiros y máquinas. Fuster exhibited paintings and I ceramics. It was my acid test. An epic journey that opened many doors for me. The rest was a lot of work.

Do you feel particularly identified with any present current of artistic ceramics? How would you define your style? What are the recurring themes that emerge in your work?

I have always said that I am a designer who makes ceramics. My ability to see two-dimensional what will later be a three-dimensional work has helped me a lot in my work. Also, the fact of knowing how to draw allows me to develop ideas on paper before dabbling in clay. I use ceramic support to promote my graphic-satirical vision of the environment.

I try to carry out series of the same idea, and most of the time I have to cook the piece several times. The fact of working and living outside of Cuba has allowed me to collide with cutting-edge technologies in the ceramic world, although I confess that having trained in Cuba has always given me an advantage. I know how to build my materials and tools.

It is no secret that in Cuba it is extremely difficult to obtain any material. That is critical and discouraging, but those who manage to overcome those pitfalls are true potters. Being an artist is something else. You have to see the world from a personal perception and be imaginative. Technological knowledge is not enough.

I really like an American artist, from San Francisco, Robert Arneson. His work is in the same structure as mine. I have never sought perfection in my work. I try that the communication with the receiver is above something perfectionist. I have been criticized for that, but it is my way of seeing the world, with its defects and virtues. Arneson is similar. His work often appears to be unfinished, but it is something that is an intrinsic part of his thinking as a creator.