In Cuba, during the 1990s, two of the popular religions of African origin underwent processes of institutionalization with the emergence of the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba and the Abakuá Bureau. These group, on the one hand, different believers of Santeria and, on the other, Ñáñigo practitioners, socially stigmatized and marked by a classist and racist disqualification strongly inherited from the colonial era.

Both institutions constitute a break with the traditional forms of worship. This, especially in the case of Santeria practitioners, works at a horizontal level and without the need for supra-family structures for the practical-spiritual life of believers. It is not, however, about cathedrals or administrative structures of the faith, as they exist in the Catholic Church. But without a doubt their very existence introduced a change, not only because they departed from custom, but because they were considered an expression of officialism.

Both one and the other arose in the context of the 4th Communist Party of Cuba Congress (1991) and the reform of the Constitution (1992). The reform defined the Cuban State as secular, taking up a tradition active since the Cuban Constitutions of the 19th century, but discontinued in fact with the practice of the so-called scientific atheism adopted during the period of institutionalization (1971-1985).

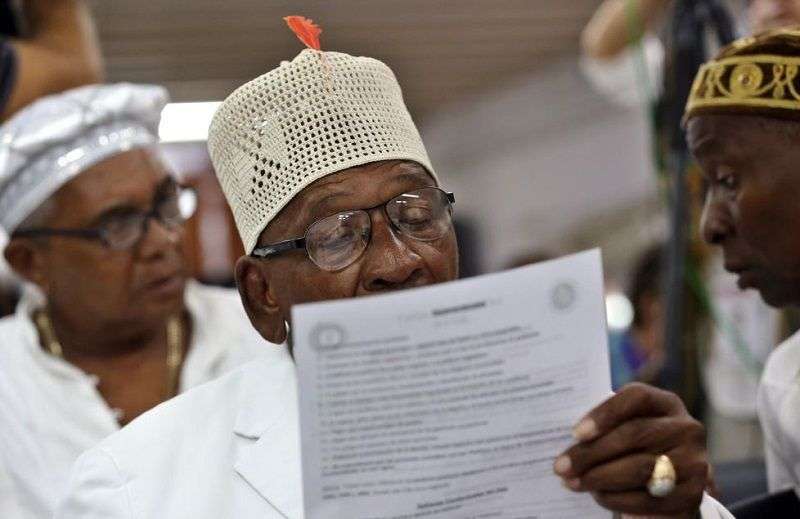

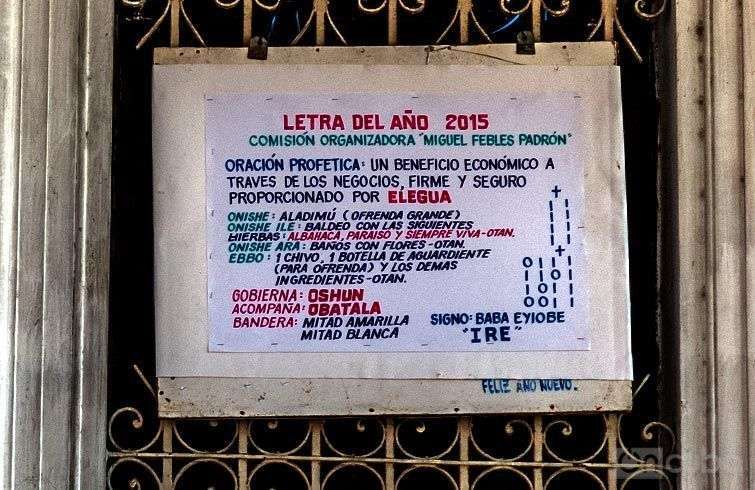

On December 31, the island’s Santeria practitioners perform the ceremony for the Letter of the Year. The sign that will govern the coming year is determined by consulting the Oracle of Ifá, a secret ritual in charge of a group of Babalawos or Ifá priests. The Letter predicts social and natural events, diseases and other events, and recommends the measures to be followed by believers in order to mitigate or try to prevent them.

Since 1992, when the Yoruba Cultural Association was created in the midst of a revival of all religions, two Letters have coexisted in Cuba: its letter and that of 10 de Octubre. Believers and observers entered into a kind of race to see which arrow hit the target more accurately. In a culture where polarization is the norm, there seems to be no room for no man’s land — and these believers are by no means the exception.

The foregoing is made more complex by the fact that there is also a Letter of the Year in Miami, and other Letters of the Year are even reported in Matanzas and Santiago de Cuba, places that have not been centers involved in this type of activity since they began at the end of the 1940s.

For some time now on the island, until now unprecedented phenomena have been documented, such as a Letter of the Year administered by women in Holguín (2021), which refers to the problem of the latter as Ifá priestesses and the expansion of Santeria in countries such as Mexico, Venezuela, Spain and the United States, and even in Russia and Finland, among others, due to the presence in those parts of Cuban diasporic communities. A point, finally, where religion and power come together. Island is not isolation, if it ever was.

In the original Yoruba culture, it is a practice that takes place in June, associated with the yam harvest, but when it moved to Cuba it underwent a transculturation process — characterized at the time by Fernando Ortiz — and therefore it was made to coincide with the activities for the new year typical of Western culture.

Eclecticism, as is natural, reigns supreme in these places: violin is played to the deities and cakes are offered to Obbatalá, two cultural artifacts that arrived in Cuba via Spain and the United States, respectively. The move to a new context forced adjustments, such as replacing the kola nut with pieces of coconut shells.

The transplanted branch of the African tree retains aspects of the original but is different. This explains why Catholic elements appear in the process of preparing the Letter. A church is attended to worship the deceased Santeria practitioners and Babalawos before the Itá ceremony1 is performed, where the main Odu2 of the year will come out of the Ifá mat, escorted by two other secondary ones that complete its fundamental meaning.

In the midst of everything, they activate practices of return to the origins that are verified in various sectors of a world that is increasingly wider and less alien. Religion does not escape this twist, manifested in the Yoruba traditionalist/Lucumí Cuban antinomy, in which areas of conflict are manifested. The tendency to return to the original “uncontaminated” and disqualify that branch constitutes, at the end of the day, an expression of fundamentalism and denial of diversity.

After several years of unification between the two, for 2022 Cuba once again had the two Letters of the year. And with more differences than coincidences due to a schism between both houses. The one from the Yoruba Cultural Association recommended patience and serenity, humility and simplicity; to avoid arrogance and bad manners, ensure hygiene and sanitary measures to prevent the spread of contagious diseases. Likewise, to pay more attention at home to the education of children and young people, and “establish favorable agreements on migration policies in order to avoid human losses.” Finally, to respect the institution of marriage. This was socially perceived as a conservative position regarding same-sex marriage, finally approved by referendum in September 2022.

The one of 10 de Octubre, on the other hand, did not pronounce on the subject. It directed maintaining the greatest possible hygiene in homes and places to avoid epidemic outbreaks and warned about the “dangers generated by crowds” in the aftermath of the July 2021 protests. But it coincided with that of the Yoruba Cultural Association in terms of ethics and family relations by recommending care in the education of minors “to avoid distortions,” the respect of parents towards children (and vice versa), adding, however, an omitted element in the first: preventing “domestic violence.”

The arrows of the new race are already thrown. Now it is the turn of the bets until next January 1st, when both come back to the fore with their signs and recommendations.

Notes

1 Itá Ceremony: It is part of the festive ritual ceremony of the cult of Ifá, and refers to the divinatory rite based on deduction, which begins the festivity. Through it, the odu is determined.

2 Odu: It refers to each one of the two hundred fifty-six signs or letters (odu) of the literary body of Ifá. Each of these codes has a name, specific characteristics and a sequential order that is respected in the ceremonies. Each year a main odu and two secondary ones are revealed.