In March she made international headlines when the Malaga Festival recognized her with the award for best actress for her role in La mujer salvaje. She was also awarded in Brazil and at the Havana Film Festival in New York. But the name of Lola Amores (Villa Clara, 1977) has been familiar to the Cuban public since long before. After years in the theater, in 2016 she leaped to the big screen in Santa y Andrés, by Carlos Lechuga.

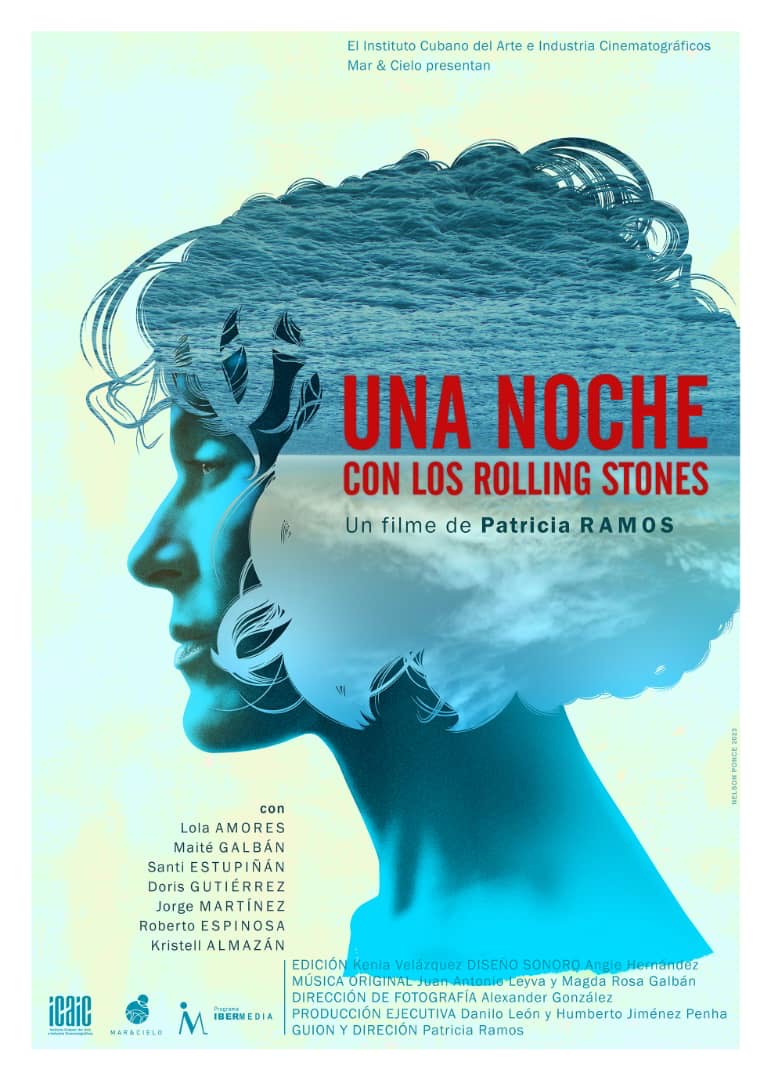

These protagonists, along with Una noche con los Rolling Stones, directed by Patricia Ramos, demonstrate the quality of her acting work beyond the medium in which she operates. We talked with Lola Amores.

How did you get to the scene, to the life of an actress?

That means a journey backward, very backward. I started doing plays in elementary school, without being aware that I was doing theater. I remember an adaptation of “Little Red Riding Hood” in which, with tremendous emotion, I threw the wolf against a couch. I remember another one called “La Moneda,” “La Visita llegará a las once,” where I played a character who received a Russian pioneer and spoke a little Russian, I thought. In primary school, we did a lot of plays.

Then in junior high school, I participated in festivals in the province, Villa Clara, which took us by bus to different towns. We worked in different conditions with children, as I was also a child. It was a very nice experience. And from there little by little I did other things. I sang in a trio, recited poems, and wrote short stories in contests organized by the librarian.

Already in senior high school, we wanted there to be a House of Culture in my town, Vueltas. We carried out a cultural campaign to achieve this: choreography, plays… A huge group of us went to take the ISA tests. There were fourteen spots that year, and I was able to get one. From that moment on I stayed in Havana and another stage began.

How did you get to El Ciervo Encantado in 2000?

When I was in the last year of college, we didn’t have a teacher for graduation. A group of girls entered into a project by a directing student named Sergio Barreiro. And Nelda Castillo was Sergio’s directing teacher. There we approached her and she worked with us a little. It was a first approach to the work of El Ciervo. It was for a short time. But it was very important because there we began to connect.

After a while I graduated and my dad got seriously sick of cancer and died in the hospital, and at that time she contacted me to be in the group. I feel that going from an experience as strong as my father’s death to starting at El Ciervo was as if my father himself left me in a place where in the future I could develop creatively, a place where I connected deeply.

I wanted to feel it like that and I really came out of that very painful experience, to that other very creative experience, where I channeled the pain, where I began to search within myself and develop an entire aesthetic taste, an ethical value, a way of seeing theater and seeing the work as an actress that has served me since then.

In El Ciervo there was strong training and a different notion of characters; many times they were not called in that conventional way.

The training is psychophysical. Nelda had done some research when I joined the group and continued to delve deeper with those of us who were with her. It was a very particular psychophysical work, which has to do with the release of tensions; we did it for a long time. It is a system of exercises that lead to a result later, but always without thinking about the result, going little by little, in stages, by scales, and going deeper into that process until one leaves more of the common places and goes deeper into the memory of one’s own body, which is something deeper, I feel.

What is sought is to get out of the representation, that is why we use the word “being” for the characters, although we call them characters to communicate socially. But for us, the word “being” made us delve deeper in that sense: of being, of not representing. The word for me as an actress is fundamental. Because I am a being that has a life of its own, that can improvise, that has its own ways of behaving, its texts. And that is so rich, so good for an actor, to reach that state of freedom. All that training allows you, that deepening allows you to reach those states of freedom and makes you at least try not to repeat yourself because you go along unknown paths, you give yourself over to what you don’t know and you find things that surprise and entertain you, of course, because you didn’t even expect it. It’s very rich, very liberating, really.

I learned a lot about the whole process in El Ciervo. As far as I could, as I always say. Putting all my endeavors and effort into it. And being there every year that I was able to be with Nelda, Mariela Brito, Eduardo Martínez, Sahily Tamayo, Sara Susaeta, Mijail Rodríguez, Sergio himself was there for a while. There are many people with whom and from whom I also learned a lot. And they helped me a lot in my process because each one has a different process in that training. And each one contributes to that.

I imagine that in some way it was a process that continued in 2012 when you founded La Isla Secreta with Eduardo Martínez. With the particularity that you two establish a different relationship with the public, conditioned by the stage space, which was an apartment.

When we left El Ciervo we had a training routine. The body asked for that work. Little by little we moved the furniture around, giving us space to train, getting comfortable. We then put a black curtain in the living room, which was very small. There was room for twenty people, if at all, tightly packed. Then we put in a wooden floor, some cushions, we put in an air conditioner, and some cans to make lights. And all of a sudden we had a small theater. We started making proposals that we then needed to show and we started inviting friends.

The proposals were a way of working for El Ciervo and that we continue to develop. When researching a topic, we made proposals that were small exercises that were not rehearsed. And we introduced ourselves to each other, with costumes, text… That part is very entertaining because many crazy things are done without thinking. And those mistakes help lead the way. We made these proposals and we came up with a show. The first was Oración.

We did many functions. We would have a chat after the show and the audience would stay to talk. We would provide tea, and bake a pineapple cake for the function and people would come and chat.

That part was very nice because having the audience so close and then having the gathering, it was like welcoming them into your home, in your space and giving them what you had. But they also gave you the opportunity to come, to share with you so closely. They even talked about their experiences, their projects. You realized that you were not so alone, that everyone was on their little islands. We made a connection between several people, projects emerged, some people became lovers there, who met and are still together and they remind us of that: “We met in La Isla Secreta.” How wonderful that is. At that stage many things happened to us, people came from everywhere, from all over the world.

We had to do a show for the neighbors because they heard that something was happening and we said: “Let’s just do a show for them.” And it was super nice because everyone went, dressed up to see the actors in the building and talked a little with us. We had a gathering and they told us their experience of what they had seen. And we also had many people like Eugenio Barba, who went to theater festivals, and passed by.

With La Isla Secreta we were in Mexico, at the Matanzas Festival, with the two shows: Oración and Jardín Adentro. We made a Café Theater there in that space, with readings for the Poetry Festival. We had screenings, we debated films, we did many things.

You speak then of a connection also with cinema.

Yes. While in la Isla Secreta I did something in film for the first time. It was a short film called La Nube, in 2013, directed by Marcel Beltrán. I was lucky that it was Marcel, a very talented person, and that I also got to do it with two wonderful actors from this country: Broselianda Hernández and Manuel Porto.

Broselianda was the person who told me the first text on film, when we improvised. And I, imagine, nervous because I had never made films and it was also Broselianda, who for me — wasn’t — is a great actress of Cuban cinema and theater. She was my guide, the voice of Broselianda. Afterwards we had a very beautiful friendship.

That was the first thing, when I was still doing Oración functions. It was a joy. At one point they cut something due to a mistake and Porto told me not to cut it. He touched me quickly: “No, no, in the cinema you have to continue, in the cinema you have to continue. It’s then edited.” I learned all those things with them. It was wonderful.

Then I did other things in the cinema. At the [International Film and Television] School I made some short films. And then I did Santa y Andrés (2016), which was more complex.

You faced a somewhat new universe, even though you were already an actress with command of your body, of what it was like to build a character. However, the media are different despite having points of contact. What was it like learning to work in films?

Yes, Santa…with Eduardo, and it was also very nice that they chose us together. They didn’t have to. Lechuga did more casting with many girls. And that they chose us together was very good, because we had a working relationship for years.

Working in films for me — and for many — is very different from theater, even more so from the theater we had been doing, with makeup, masks, more out of daily life. But the training of El Ciervo and the one we followed later is wonderful for making films, it is the basis for an actor. We had been doing that year after year. It’s like you walk and walk and you find that then you have the shortest path to do other things.

Of course, you always have to try not to forget, because it is not about looking for results, but for processes. Cinema has a lot to do with what we learned. When I’m making films, it’s funny for me, for example, that there are a lot of people working. We all did it in the theater: the costumes, installing the cable, everything. And we also had disposition training, to be willing to do it, to not wait for the other.

These are things about theater that help you, give you resistance. Because cinema apparently does not involve physical training, but it does require resistance of your mind, of your psyche. You must have mental strength to be able to be in extreme conditions because we spend a lot of work making films. There is work all over the world, but in Cuba we have complex conditions. And you have to be willing, focused, wanting, and without the nonsense of judging, of criticizing. You can’t waste time; you have to be there. Therefore, for me, even cinema has a spiritual part, of disposition, of being ready for something that is not you who write it, you dedicate yourself to the work of others.

Watching La mujer salvaje I thought you jumped from Santa, an introverted character, and faced Yolanda, so different. Tell me about those contrasts and what it has represented for you as an actress when it comes to making films, because it has allowed you to unfold yourself, to see yourself in totally different situations.

Acting in cinema follows the same path as theater, of dedicating yourself to a new investigation each time, in which you don’t know where you have to reach. You discover it together with the director. The nice thing about that is that each director comes with a proposal and you give of yourself. If you are alert to what he wants, you don’t have to reach the common places, what you brought from the previous one. What helps is the passion with which each director comes with his project.

One is very alert, sensory speaking, for words, intentions, what they want. That is important to work on the character with its particularities. Giving yourself over to the director’s obsession and not your own, because you are always defending a commonplace.

You have worked with Carlos Lechuga first and now with Alan González. They are young people who don’t care about the risk, they are always ready to let you flow. I’ve heard you talk about that.

Yes, they are more open to the actors’ proposals. A director has to be, I think, very capable of directing what the actor finds.

Tell me a little about the international awards you have obtained. You have been recognized at festivals in Mexico, Miami, Brazil, you won the Silver Biznaga for best actress at the Malaga Film Festival, with La mujer salvaje. You have gone from starting in cinema to becoming a well-known face who must be mentioned when talking about contemporary Cuban cinema. What does it mean to you?

Well, with these awards sometimes I say: “Wow, people are liking me.” I always think that awards are something that one does not look for, that they arrive and one is very grateful for them. Every time I receive recognition I think of the entire team. I tell myself how happy I am. What a joy, because it’s like confirming something for the rest of the team. As if to tell them that I did the best I could and someone else sees it. That moves me, it even makes me nervous, because it moves me.

When people work as a team, they come together a lot and it is a joint effort. I really like teamwork. And in the projects that I have been in, people are very important to me. The photographers, the wardrobe people, then they all remain friends. Every time I’m awarded a prize, I think of everyone, of the joy they are going to feel. And then they write to you: “Lola, you’re really something”, that nice phrase.

Those who don’t know you don’t know, but I have to say that in the case of Lola Amores, one of the factors that determines success is her humbleness. Humbleness has determined your career, both in the theater, when you were there, doing everything, in the role of both director and actor, and in film as well.

Thank you. I feel that it takes a lot of work to make movies, like theater. But these recognitions have to do with the effort we have made to achieve it. And that part is very beautiful. If I look at it like that, I’m very happy. Then I forget, the moment has passed and I go on to something else.

Besides Una noche con los Rolling Stones, what will we see you do next?

Well, now I’m in a project called La levedad de ella, by Rosa María Rodríguez, still to be filmed. She gave me the script and I love it. It is a project that will give me a lot of joy in terms of research and connections with her, with the text that she gave me, which is very beautiful. I know I’m going to really like doing it.

In Cuban cinema, some female characters and actresses have set a standard, who have become the face of cinema for a long time. I’m thinking of Lucía and Adela Legrá, Raquel Revuelta, Eslinda Núñez. I think of films that came later, of Isabel Santos, Beatriz Valdés, we could mention several names, to which I think yours is being added. In your last two films, you have shown that you are beginning to be a recognized face. How has your relationship been with the women you have played? Have you ever thought about being next to the names I just mentioned, who have made such an impact on Cuban viewers?

Well, you put me there on that list. And I see it from my point of view, from my life. I’m just doing things. I love being among all the actresses, I love being among the people who are doing things, who have done things like that in Cuban cinema. Those wonderful films that we have in our cinema, all those names of great actresses, who I admire and know, as a Cuban, what it has been like to make films in Cuba, and what the characters they have played have represented for us. If I’m on that list, I love being on that list. And if not, the same. Because I feel like I’m making movies with everyone. And I draw from all of them and they are the basis of where I am now, where I stand, where I build. I also thank all the actresses who make films in Cuba, and the theater people. Theater actresses too.

You asked me about my relationship with Yolanda and Santa. For me, the relationship with the characters has a lot to do with the processes, the starting points. When I started doing Santa y Andrés, Lechuga gave us about thirty-odd questions related to the character, what it likes, what it dreams of, the girl’s games… And I started to answer in a somewhat extreme circumstance, my mother had cancer and she was very ill in the oncology hospital in Villa Clara. So I began to respond through my mother, through my mother’s countryside experience. From deep in the countryside. All the research I did for Santa had to do with my family.

For me, it was wonderful because, although I had heard those stories at another time, in that circumstance they had another dimension. I became aware of everything that I, as a human being, through that research, had evolved, advanced, or experienced in my life, from my point of view, from my dead. I was very moved and I was left with that feeling every time I see Santa, seeing my family’s entire journey and that research I had done with my mother. That we had fun and everything, despite the extreme situation we were experiencing, while we did research on all that.

With Yolanda, it was another experience, because I did it living in Marianao. And the director of the film, Alan González, lived three blocks from my house. That feeling of building a character living in Marianao, with Alan feeding me with videos, watching things… That research and those moments in the middle of the pandemic, make the character see it from a very particular sensation of space-life and I do not forget it. And it takes me to all the women in that area. So the experience is very intense as well.

I think that the opportunity to play those characters came about thanks to the fact that, despite the circumstances that the island is experiencing and that emigration is hitting harder and harder, you have decided to stay in Cuba. What does it mean to you to be a woman, living in Cuba and making Cuban cinema today?

Making films in Cuba, or any other manifestation, requires strong resistance. It is a life attitude. With so many people gone, things have also been changing. I think that all those people who are abroad can also get involved in Cuban cinema. That’s what’s great and, what’s more, they make movies wherever they are. There are many friends in Spain making films, in Miami… Things are changing in that sense and there is a network of people making films in different places that is very interesting.

Being here and trying to do it here is a battle that makes you strong and is intense, yes; but it is achieved and there are results too.