After the liberation and the Agrarian Reform, the next step of that Revolution, more than 60 years ago, was education. The massiveness of that great leap opened up a greater and more diverse space for participation than any other in the process of radical transformations in Cuban society. Not only downwards, but upwards. Indeed, while tens of thousands of young people taught hundreds of thousands of farmers and humble workers to read and write, in the countryside and cities, society was becoming a great school (Che Guevara dixit), in which men and women dedicated to science and thought also had to be trained. Fostering a vanguard of scientists and intellectuals as part of that educational revolution was conceptually consistent not only with mass participation but also with laying the foundations for social development, achieving independence and sovereignty, and advancing equality and social justice in real terms. The revolution was going to be a fundamental social and cultural change, not just in the economy and politics.

The Raúl Cepero Bonilla Special Institute was the first pre-selection school created by that Revolution, in December 1962. I was fortunate to be one of the 58 students, from all over Cuba, who converged for that ambitious project. In the final months of the 1962 academic year, we had been summoned to take a battery of intellectual ability tests, designed by a team of psychometric experts from the United States, collaborating with the Ministry of Education (MINED), then headed by Armando Hart.

The selection criteria for the call had been guided by the results of the mathematics subject among secondary school students, because according to the psychometricians’ Gaussian curves, those who were good in that subject had a higher IQ, and could also be good in other subjects. However, the pedagogical conception of that pre-university project was much more comprehensive and advanced than suggested by a troop of mathematicians or “Abelarditos,” as those who are now called nerds were then called.

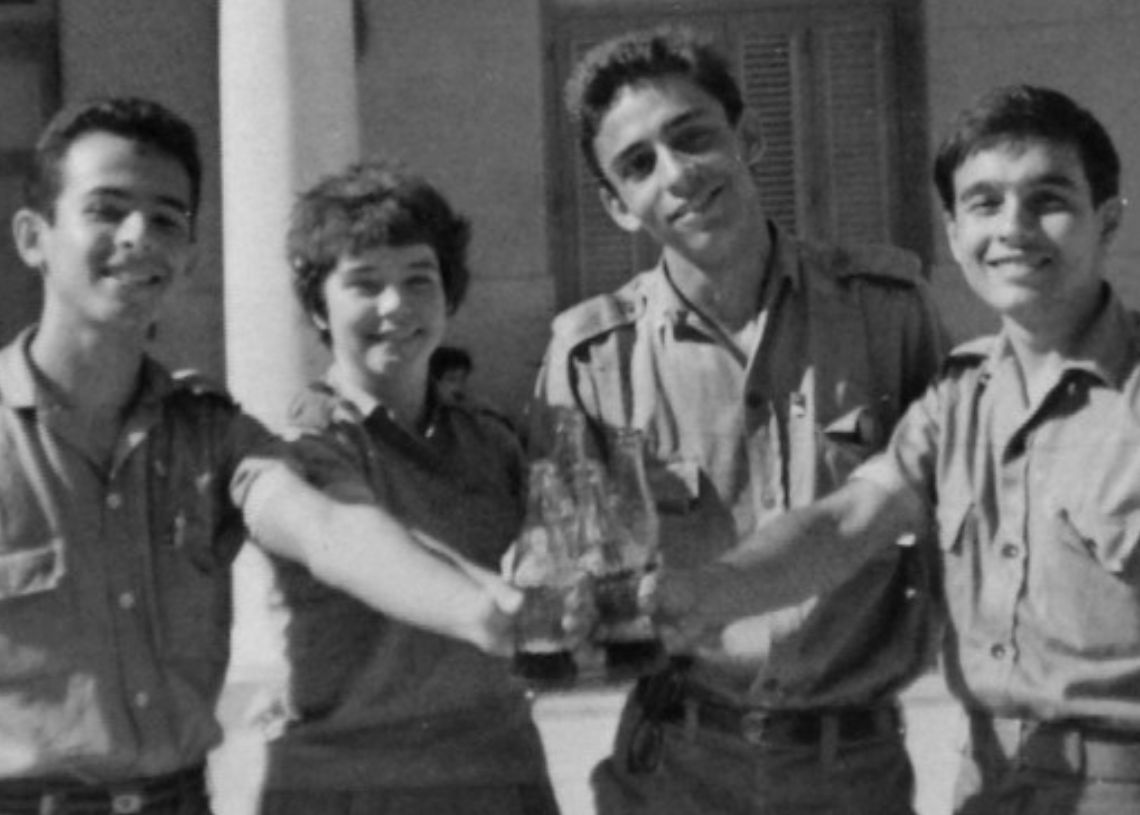

A few days ago, some of the survivors of that project gathered to celebrate the 60th anniversary of our graduation in 1965. And they asked me to say a few words. When I read them, I said they weren’t a chronicle or a history of the pre-university project or us, but merely an evocation. I’ve read them again, and they seem to me to be a glimpse of that founding historical moment. But I also believe that learning about that project is worthwhile today, because it still holds lessons for the more current present.

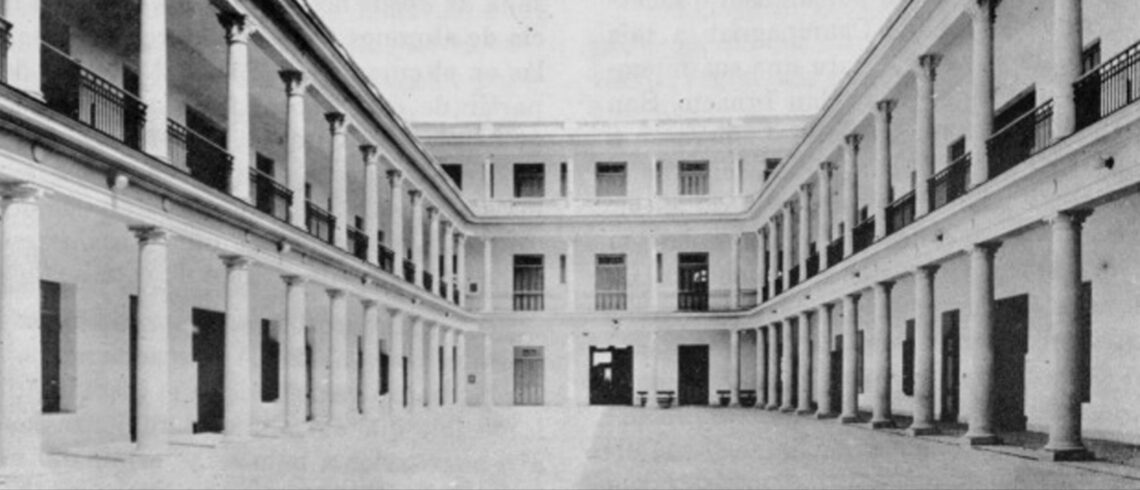

How many things had to happen for us to meet at that nuns’ school, the Apostolate of the Sacred Heart, on 21st and Paseo, one December morning in 1962.1

We were also the Revolution, our lives intertwined and interwoven from that moment on.

We came from places as diverse as Holguín, Camagüey, Vueltas, Cárdenas, Nueva Paz, Cabaiguán; from Havana neighborhoods like Old Havana, Luyanó, Guanabacoa, Lawton, Víbora, San Miguel del Padrón, El Pilar.

Our parents were working people, blue- and white-collar workers, or lower-middle class, in factories and sugar mills, where they earned their living as drivers, watchmakers, teachers, grocers, railroad workers, seamstresses, housewives, secretaries, police and naval officers, small farmers, doctors, and in other diverse occupations.

We came from private and public schools, religious and secular, and from the boarding schools under the brand-new scholarship program.

We wanted to be physicists, mathematicians, biologists, chemists, or engineers, architects, doctors, or psychologists, writers, journalists, linguists, artists. Others of us wanted to know everything or didn’t know what we wanted.

Some spoke English as well as or better than Spanish, because they were repatriated or had studied in bilingual schools; others, almost none at all. Some played the piano or painted, read all kinds of literature, liked concert music, had a talent for singing, dancing, and even writing lyrics for songs and parodies. Others, none of that, but we were still passionate about learning everything new that pre-school presented to us: playing the guitar, folk dancing, pottery, xylography, theater, auto mechanics, electroplating…

We had heard Fidel say that the future of Cuba had to be a future of men of science, of men of thought. And we thought that Cepero was just that.

The country was a hive of activity then. We had gone to teach how to read and write with our classmates or friends, while other friends and schoolmates were leaving Cuba with their parents, barely giving us time to say goodbye.

Unexpected things happened every day.

When we arrived at the Cepero, the Missile Crisis had barely passed, when we were on the verge of thermos-nuclearizing everyone on the planet, as Roberto Fernández Retamar wrote.

Havana was a discovery for many of us who came from other provinces — almost half of us. On weekends, we walked up and down the Rampa, along the sidewalk where Coppelia ice cream parlor would later be built. We toured a Havana where pizza was still an exotic food, where it didn’t sleep all night, and where you could see it like a sea of lights from the top floor of the Habana Libre Hotel, where you could enter without having to consume.

We went to the movies nonstop, watching and discussing all the controversial films of 1963 and 1964: La dulce vida, Accatone, El ángel exterminador.

Those who taught us were or would soon be very prestigious intellectuals and university professors. Beatriz Maggi, César López, Ezquiel Vieta, Jaime Sarusky, Ángela Grau, Marta Pérez-Rolo, Nuria Nuiry. Our literature and history classes could have been courses at universities anywhere.

More than a secondary school, the Cepero was a kind of Renaissance agora, or rather, it sought to be.

Our principal was Francisco Calle Blanco, better known among veterans of the Spanish Republic as Manuel de la Mata. A Spanish anarchist and authoritarian, whose ideas about education were so advanced that they are still novel today. He didn’t believe in exams as a measure of learning or in grades as absolute values for academic performance. He repeated that although we Cepero students were a select group, we couldn’t be an elite locked in a bell jar, oblivious to what was happening in politics, culture, the country, the world, or removed from manual labor. We had to master how a library worked and how to pick coffee, watch, and discuss theater works and modern dance being performed in Cuba, avant-garde art, listen to and engage in dialogue with writers, scientists and political leaders, both Cuban and foreign.

But it wasn’t easy to defend that incubator of enlightened and thinking scientists that was the Cepero at the dawn of a revolution that didn’t follow a predetermined path, besieged by formidable enemies, crisscrossed by its own conflicts, amid a political culture in turmoil, where anti-intellectualism and dogmatism, feudalism and sectarianism were not uncommon, despite being denounced by the leaders of that revolution.

Many of us had lived through the Year of Literacy far from our families, teaching farmers and humble people to read and write; we knew that education came first. But we arrived at the Cepero during the Year of Planning, when mechanisms of control and centralization were being established.

The Cepero was an experiment in educational decentralization and had to contend with those who equated planning with bureaucratic control. There, we went through the Year of Organization and the Year of the Economy, and the Year of Agriculture, when we graduated.

We had already been picking coffee in the Sierra Maestra less than a year after we met. And we were there when Hurricane Flora hit the Oriente province, between October 4 and 8, 1963.

Perhaps no experience united us as much as that cyclone we shared in person. More than 60 years later, surely each of us could recount in vivid detail that march through the wind and rain, between where we stayed and the coffee warehouse where we took shelter for a week.

The Cepero was our launching pad for life, the life we would live from then on. It was the crossroads of a path that would branch out into as many paths as each one of us, and that would take us to unimaginable destinations.

There we began to learn what it meant to become men and women of science, and above all, of thought. And to share a common heritage, which we identified as our own, regardless of our current diversity or where we are. In fact, we learned that this diversity was not a sign of confusion or loss of meaning, but the opposite.

So many things happened in those three years, unfathomable and remote today, but above all, we grew and became politically involved, in the best sense of the word. Because we learned to look and see beyond our small world.

Among those legacies and lessons, there is one we treasure most deeply, and which we can see here today, 60 years later: the ability to laugh, among ourselves and at ourselves.

In a recent survey among the Cepero students in our WhatsApp group, I asked what had been the most difficult thing about adapting to life during that pre-university period. What was surprising, for those who don’t know us, was the extremely high degree of coinciding responses.

That survey and the event recalled by everyone as the hardest part of life, living in that boarding school, reminded me of some verses. Although I am no longer the full-time neoclassical poet I was at 15, I was able to remember a sonnet that goes like this:

I tremble when I look at the fierce guillotine

dripping with Girondin blood.

I tremble when I climb the Andean tower

with the sight that takes its chimera to the extreme.

I shudder when I walk through the meadow

my gaze enraptured before the holm oak

that tears the faint, fine breeze

through its gray wooden fingers.

But if sovereign nature has forever

endowed the world with many emotions,

what makes me tremble, human misery,

and makes me sustain a horrible struggle

is getting up early in the morning

and getting under the shower.

Cepero Bonilla Institute, 21st and Paseo, 1963

________________________________________

- From here on, the text reproduces what I read on the 60th anniversary of the first graduation from Cepero Bonilla (FEU House, June 28, 2025).