When three years ago, UNESCO declared the knowledge of Cuba’s master rum makers an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, it not only crowned the erudition of eight generations of Cuban alchemists, but also tacitly honored a history aged for more than a century at Nave Don Pancho, the so-called Cathedral of Cuban rum; although there is still some clarification to be made about that specific term.

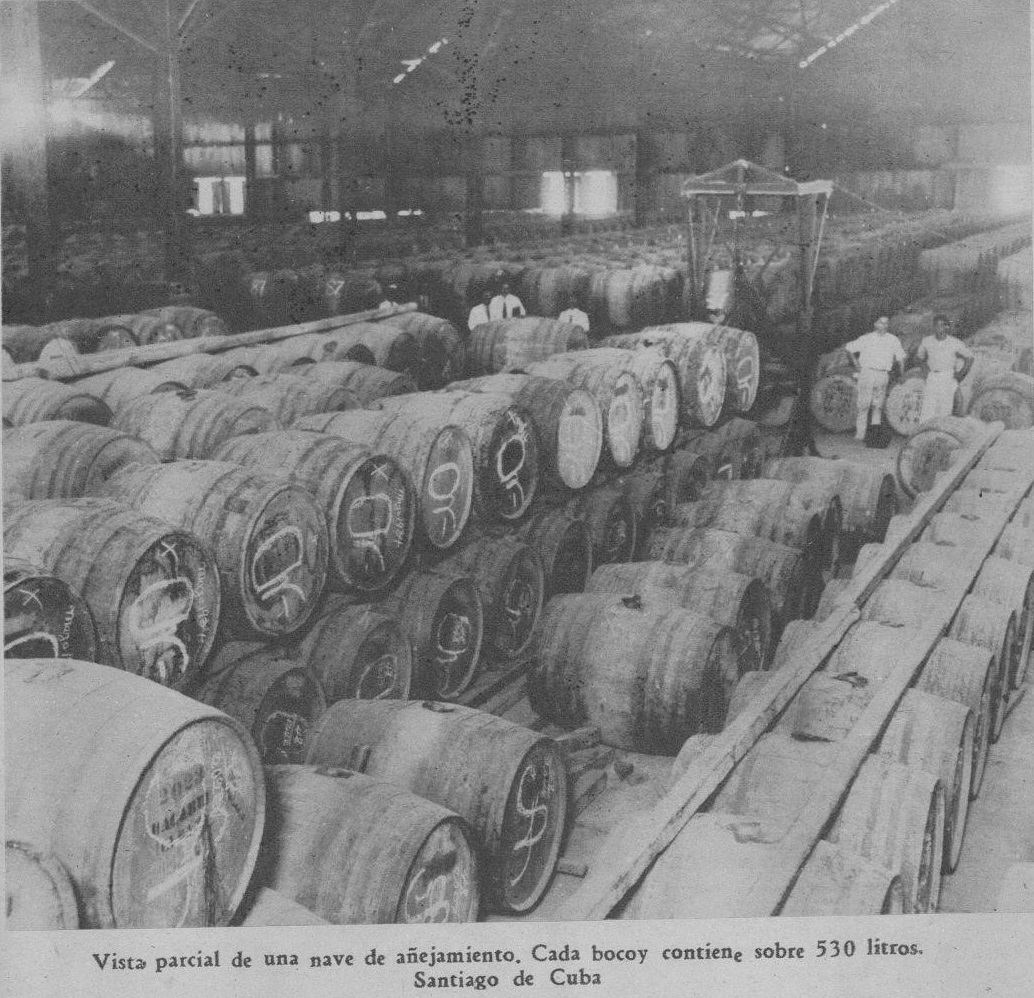

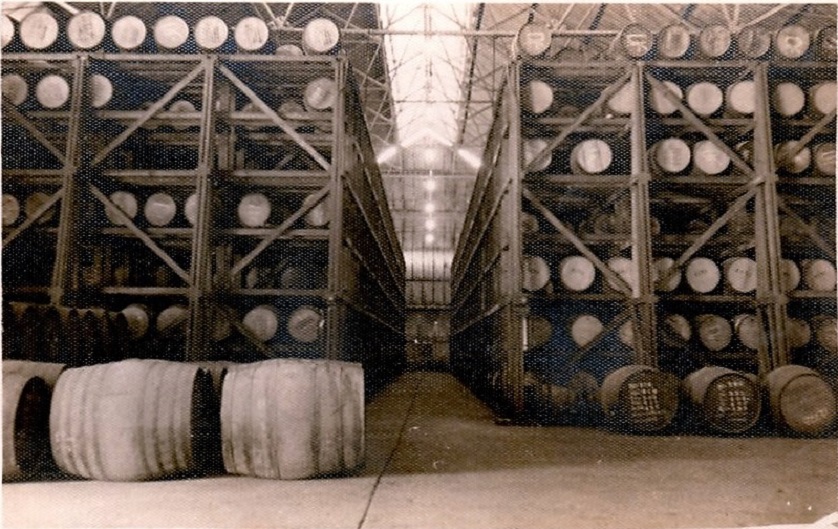

Located near the bay and the train station of Santiago de Cuba, a city where the echoes of time fail to escape the mountainous coliseum, the old rum making establishment safeguards the base or mother rums — as connoisseurs call aging distillates, the most important liquid good — which, when carefully combined in a laboratory process — that is, scientific, artistic, innovative, not so mysterious — become rums of different ages, aromas, textures and flavors that have enchanted palates around the world.

Surrounded by myths and hermetic like a bunker, the facility’s yellow facades and red roof tiles are a symbol of success, a “postcard” often shown to leaders and high-profile guests in a dreamlike sensorial experience the people cannot dream of. Due to its unparalleled heritage value, it is a living archive of a recipe, a technique and a dedication blended like a loop of a distilling tradition dating back to 1862, passed down uninterruptedly until memory was translated into the country’s identifying flavor.

Between wooden beams and barrels with a scent of nostalgia, the Nave Don Pancho treasures in its murky silence a legacy and a spirit that cannot fit in a bottle.

Cendoya’s warehouse

As soon as he set foot on the Muelle de Luz del Santiago in 1891, his gaze fixed on the steep township bustling in front of him, Julián Cendoya, the representative of the New York shipping company Ward Line, struggled in the labyrinth of his thoughts about how much further his destiny could take him. He was then in the prime of his youth. Agitated without madness, toiling at work like someone listening to an inner refrain, he vowed not to rest until he had established the pulse of his family name. His eyes widened. Twenty-five years later, mentioning him meant alluding to the man behind the province’s great merchant businesses.

By 1918, as magnate of the Santiago Terminal Co. and the Santiago Warehouse Co., Julián Cendoya controlled shipping and port operations, including docks and sheds, primarily related to sugar exports. Both companies were incorporated under the laws of the United States, his country of citizenship, although he never forgot his Basque origins. An image of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, a painting of Guernica’s traditional tree and picturesque photographs of the city of San Sebastián decorated his office.

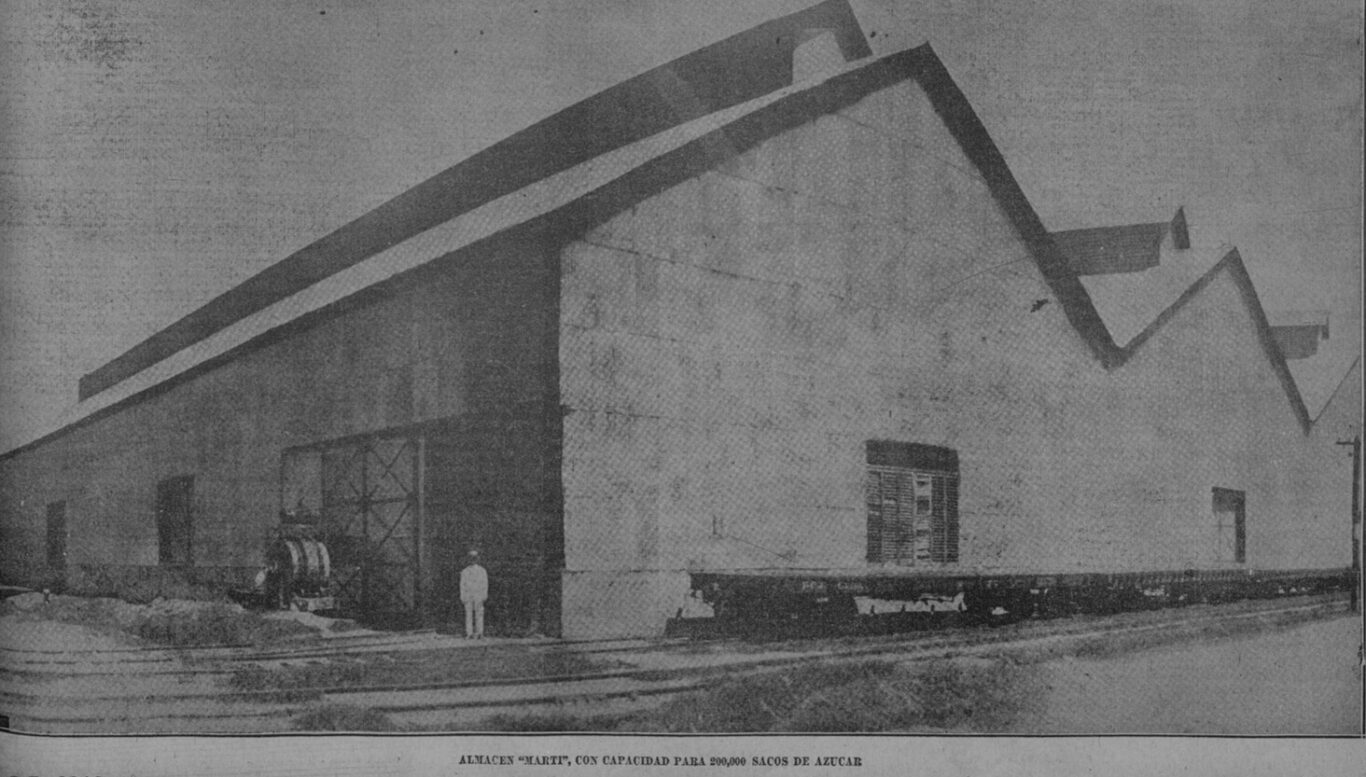

In particular, the Santiago Warehouse, founded in 1916 with a capital of 250,000 pesos and the exclusive task of storing sugar in sacks, had its flagship warehouse at the intersection of Paseo Martí and Avenida Michaelsen (the company owned four other smaller warehouses). With an area of 6,500 square meters, the building, as huge as a ship, housed offices, several Siamese sheds and enough space to store 200,000 sacks.

The corporation averaged one million sacks during its boom harvest, when demand for sugar soared during the bitter days of World War I. But when sugar exports contracted and prices plummeted in the early 1920s, the island’s banks went bankrupt and companies overly dependent on the sugar sector became as rickety as the cows that characterized the era, Cendoya realized that its long-term sustainability was fading. So he opted to put its flagship warehouse up for sale.

Under the bat’s wings

On the contrary, by 1920 Bacardi was experiencing its own boom. The bat brand, which since the late 19th century had been valued as the Rum of Kings or the King of Rums, was pushing for the construction of a completely new distillery to meet the ever-growing demand for its rum.

In parallel, and adjacent to the rum factory, the modern Hatuey brewery was built, which included a bottling plant, ice factory and almost Babylonian gardens for publicity and social events. Both facilities would be inaugurated in February 1922. The company also employed hundreds of workers and aimed to conquer new foreign markets.

The Cendoya warehouse was an irresistible offer for the Bacardí clan. It was formidable in size, located one kilometer from the docks and next to the Central Railway line, with the advantage of a branch line that entered diagonally into its premises, with a level floor for transportation cars. This facilitated loading and unloading goods, storing them and transporting them quickly to the shipping point. As if that weren’t enough, the warehouse was located almost opposite the Bacardí factory itself, where the original still was installed during the romantic era of Don Facundo. They had had their eye on it too many times.

It was the right place. So Don Emilio Bacardí didn’t think twice and bought the warehouse from Julián Cendoya in April 1921 (for a precise date, I am grateful to Carlos Edgar Martínez Bueno, director of the Rum Museum in Santiago de Cuba). Once the property was acquired, the renovation work began, along with the construction of racks — vertical wooden shelves where industrial quantities of barrels would be stored for their prolonged aging nap.

Better known as Don Pancho

True to his name, Francisco Savigne Lombard was affectionately called Don Pancho. He was born in 1869 of French descent. With a long, sharp Paraguayan sword, he earned the rank of officer in the Liberation Army and, after hanging up his machete, worked as a foreman in the Ti Arriba area. One day, he decided to come down from the hills to seek a better future for his children in the city.

According to a family story — kindly told to me by Grisel Álvarez, Don Pancho’s granddaughter living in the United States — he was working as a stevedore at the port when Totén Bacardí, one of the family business’s assistant managers, stumbled upon him, no less astonished. He immediately suggested taking him to the factory, where he asked the board of directors to employ him as head of the brand-new aging cellar. Savigne Lombard was related through his mother’s side to Elvira Cape Lombard, Don Emilio’s wife, and for years he was in charge of the Santo Domingo estate, owned by his cousin in the La Maya area.

“His innate bonds, combined with his personal qualities and impeccable moral character as a worker, earned him the absolute trust they placed in him, leading him to be appointed the first manager of the aging cellar. Not only would he be respected by all in this role, but he also established a line of work that made him a paradigm for those who succeeded him. Even after Don Pancho’s physical death, work would continue there with the same rigor, selflessness, respect and love,” says Carlos Edgar Martínez.

Along with his loyal collaborators Hipólito Garrido and Enrique Guerra, Don Pancho established a work system as precise as the pendulum clock in his office and, with integrity and pride, preserved the company’s true gold mine. His tombstone bears the inscription that he died on January 10, 1939. It is said that he was the victim of fulminant pneumonia.

I have been able to find nothing more than these brief notes and a sepia-toned portrait of this enigmatic figure. Not even in several newspaper sources I’ve consulted is there any reference to his name. Everything indicates that he worked as a monk in the shadows, but he left his light, to the point that his name remains as the cellar’s sign. His imprint must be studied.

Unexpected visit

Many years later, facing the new-age platoon, at 8:40 a.m. on October 15, in the revolutionarily baptized “Year of the Agrarian Reform,” Bacardí executives scribbled their signatures on a document handing over the 98-year-old company to the Cuban state. The dramatic nationalization included all physical assets and facilities, including the warehouse where the spirits slumbered in their turbulent repose. Those reserves would be sufficient to keep production running for decades. Now the challenge was to continue producing rum equal to or better than Bacardí.

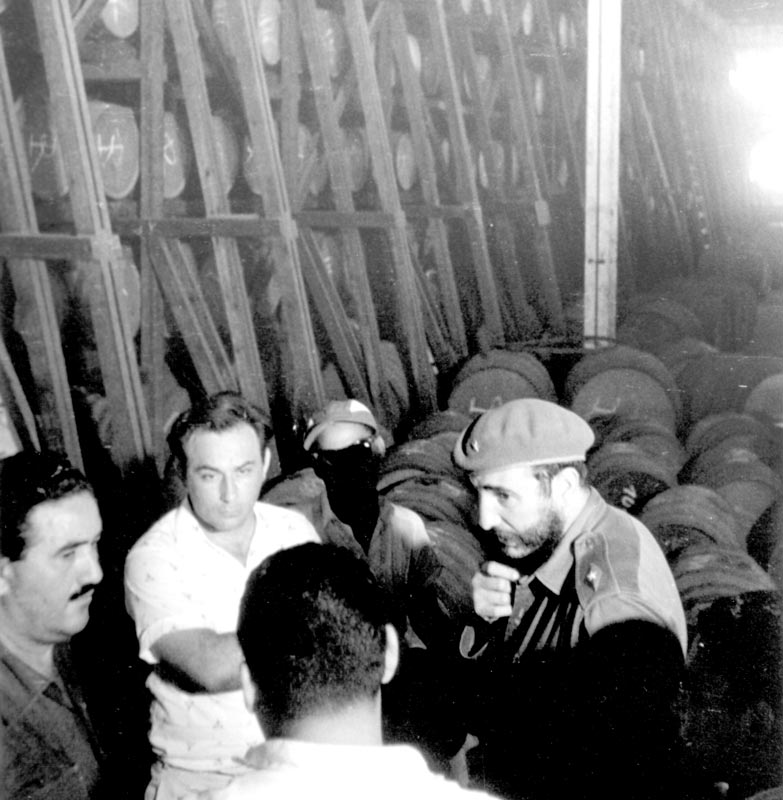

Three years later, on the afternoon of July 16, 1963, Commander Fidel Castro was returning from inspecting the hydraulic works being built west of Santiago and from lunch with the Renté workers when he passed by the warehouse, which displayed the sign along its wall facing Paseo Martí: NATIONALIZED BACARDÍ.

“Let’s go visit Bacardi,” he suddenly ordered. And right there, the caravan detoured to the factory. Since it was Saturday, only a maintenance crew headed by Gilberto Cala remained at the facility at that hour. “Look how I’ve come to meet the little man!” exclaimed the humble worker, unaware that his “cheerful” — naive, I would say — disparagement could be offensive to the man everyone considered the big man. Fortunately for him, those were different times. The anecdote of that unexpected visit was told to me — and is recorded in an unpublished book of testimonies he wrote — by the late José “Pepín” Hernández, a Bacardi employee in the 1950s and later director of the Rum Museum for several years.

Feeling humbled by his luck and with no more expertise than his years of practice, Cala agreed to show the delegation the bottling room and the rest of the facilities, even offering Fidel a taste of Añejo, the product being bottled that day. Fidel asked to examine the aging cellar, but Cala excused himself for not having the key. Security guard Reynaldo Hermida, then head of what we now call Physical Protection, came to save the awkward moment by offering to open the cellar.

Korda’s camera recorded that moment there. At least two photographs have emerged: one of Fidel speaking with Cala while holding a bottle in his hand, and another of Fidel in front of a shelf full of barrels in the aging cellar. Che Guevara also toured the facility in 1964, as part of his duties as Minister of Industry.

A charming warehouse

Between the exuding wood and the enigmatic whisper of time, the Nave Don Pancho encloses an intoxicating atmosphere. Like a treasure ship, all kinds of mysteries and legends throb beneath its visible hull.

From its proximity to the railway line, the myth arose that the faint vibration caused by the passing trains benefited the spirit inside the barrels. Some theories centered the key to the process by which the distillate aged in American white oak barrels; understanding that, being hard and relatively porous at the same time, the wood of the barrel, when interacting with the rum, absorbed some of its strongest flavors while simultaneously imbuing it with its own. Meanwhile, other explanations indicated that the rums’ uniqueness was due to the waters of Santiago or the molasses brought in barrels from the Algodonales sugar mill.

There has also been controversy surrounding the famous “secret formula.” It is known that since the time of Don Facundo Bacardí, the Catalan founder, knowledge regarding rum distillation and blending was passed down through experience. The master blenders were — or have been — the “chosen ones.” Almost a brotherhood in a locked room. They not only responded to the desire to produce elixirs to captivate palates and, thus, fatten the consortium’s coffers, but they also assumed the supreme mission of protecting ancestral rudiments from upstarts.

However, the main and true “formula,” rather than a mystical one, has been one of technique and perseverance. The product was the culmination of a tempered process of trial and error: better filtration here, more aging there; meticulous attention to temperature, ventilation, light and shade; ensuring the degree of aging and quality of the molasses; the precise choice of wood for the aging vats…. In short, the result of mastery in balancing a set of factors with selflessness, art and skill. There is no mystery in rum making.

For decades, the people of Santiago de Cuba have boasted that the character of their rums has not been replicated, at least not in terms of flavor. The wealth of the iconic aging cellar undoubtedly had a lot to do with this.

Recently, Nave Don Pancho has been called the “Cathedral of Cuban Rum.” However, what has been taken as a happy slogan with a modern aftertaste is somewhat inaccurate. Strictly speaking, it must be clarified — a thesis shared by Carlos Edgar — that this name was established long before as a promotional seal for the former Bacardi Rum factory. No matter how intoxicated we may be by the emanations of current narratives, history is neither bottled nor evaporated: it is carried in our conscious.