The dense forest of Cuban music filled up, over the course of the 20th century, with popular musicians of the highest level, to the extent that after the 1940s, it was not very easy to stand out, especially in Havana. Those born in the “city of seduction” were joined by others from all over the island who came to try their luck. It was in that atmosphere that Celia Cruz made her debut as a young singer, eventually becoming one of the most important voices in Cuban song of the late 20th century.

Celia was born in a working-class family in the Havana neighborhood of Santos Suárez. Some say she was born on Oct. 21, 1924; others say she was born four years earlier, and some say it was in 1925. Her father, Simón Díaz, was a stoker on the railroad, and her mother, Catalina Alfonso, a housewife. She was the couple’s second daughter and had three siblings: Dolores, Gladis and Barbarito. When she was still a young girl, people noticed her talent for singing. First, there were the lullabies that she learned or invented, to sing her siblings to sleep. Then, thanks to the radio, there were songs she was always willing to sing. In fact, a stranger once gave her a pair of shoes as a reward for her efforts, which were supported by listening to her mother, who had a tremendous voice.

Despite the family’s low income, she was able to attend school from a young age. Once she finished elementary school, she began studying to be a teacher, as her parents had asked her to, but shortly before graduating, she abandoned that course and enrolled in the National Conservatory of Music to obtain an education in the discipline that had always interested her most.

During that time, she began singing on the radio, and in fact won an award on the popular program “The Supreme Court of Art,” for singing the tango “Nostalgia.” During that period of training, she became interested in the styles of Paulina Álvarez and Joseíto Fernández. She entered the world of show business by singing in the clubs and cabarets of Havana.

By the 1940s, Celia Cruz had become a very well-known figure in all sorts of venues in the Cuban capital. She had a wide-ranging repertoire with an abundance of songs from the guaracha and son genres, as well as boleros, which she knew how to perform with an eloquent sensuality. Not many people known that she sang with the accompaniment of the Obdulio Morales orchestra, and that she performed Afro-Cuban music, which years later, in the 1950s, made it possible for her to record an album with that repertoire. (In 2015, an anthology has come out of the EGREM recording company’s files that include recordings by Celia with others by Merceditas Valdés). She recorded with the outstanding orchestra of Ernesto Duarte, that unflagging Cuban musician who composed “Cómo fue.” In 1951, Celia recorded in a studio for the first time. It was a 78 vinyl record that featured the songs “Cao cao” and “Mata siguaraya”.

In the 1950s, Celia participated in different actions that would have major importance for her career. She participated in the show “Las Mulatas de Fuego” (The Fiery Mulatas), staged by choreographer Rodney at the world-famous Cabaret Tropicana. She was discovered there by the director of the band Sonora Matancera, who proposed that she join their group to replace a Puerto Rican singer, Mirta Silva. Celia agreed, and in a short time, she became the Sonora’s most charismatic singer. At the height of popularity on Cuba’s stages, the legend of “La Guarachera de Cuba” and the “Reina de la Rumba” (Queen of the Rumba) began to be woven.

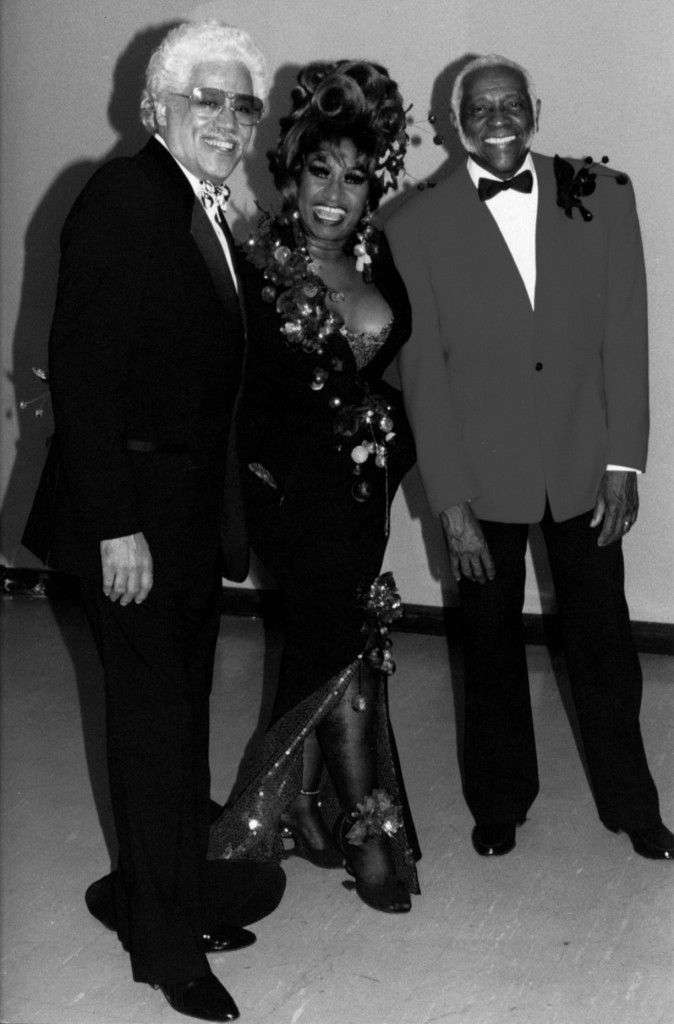

In 1959 she traveled to Mexico, where she remained for a year, later residing in the United States, and she participated intensely in the salsa movement. That was when she began to be called the Reina de la Salsa, traveling throughout our America and Europe, defending the clearest colors of Cuban music. She continued to perform until very shortly before her death, on July 16, 2003, in New Jersey.

I grew up listening to Celia Cruz thanks to tapes and cassettes that were passed around. However, it was by pure luck that I was able to attend a concert by Celia Cruz one night in the 1990s, at Madrid’s Plaza Monumental. For the Spaniards, it was a frequent occurrence; for me it was the first time. Alberto “El Canario” began playing, and I listened tranquilly to their set leaning on a fence in the plaza. But when they announced Celia, I practically fell over. I wanted to get closer to the stage, and halfway there, I discovered an enormous Cuban flag and ran to envelop myself in it. There, we recognized each other, a tight handful of Cubans, as Celia sang “La Guantanamera” with Martí’s verses. When the flag touched the stage, Celia stopped singing. She embraced the flag and covered it with kisses. Those of us who were underneath the flag hugged each other without knowing each other, without knowing where we all lived, but recognizing each other as Cubans. Deep within us, those songs were ringing, songs that Celia once began singing in Cuba and then scattered throughout the world, extolling our identity.