Why did Ibrahim Ferrer have to shine shoes if he had the potential to win Grammy Awards, Oscar nominations, and sell out theaters around the world? Let’s take a look at the scene. Slow motion: we see the audience, excited, applauding. A close-up of the musician. He is crying of happiness behind his eyeglasses, wearing an expensive suit. The same man that went from singing with Pacho Alonso and Benny More to being forgotten, and then, at the end of his life, remembered again. Was Ry Cooder his salvation?

The book “How Cuba made the world dance,” by Cuban journalist Juan Carlos Roque, offers a few answers. The answer to the question above, for instance is “No.” That’s what Juan de Marcos Gonzalez, the former director of the Sierra Maestra band, and founder of Buena Vista Social Club along with Cooder, says: “Ry Cooder never sold more than 200,000 copies of an album in his life. I think he’s an excellent musician, but the success of Buena Vista Social Club was not determined by his participation.”

And there’s more. When asked if Ry Cooder was conveniently under the shadow cast by Gonzalez, he replied: “Not under my shadow, under the shadow of Cuban music and of the BVSC musicians.”

“I always like to mention the name of Juan de Marcos Gonzalez,” said Barbarito Torres. “He deserves our respect. Sometimes people forget that this project was his idea, and that it was him who “sold” it to Nick (Gold). It was then that Ry Cooder was brought in as a producer, because he was a renowned figure internationally, and had experience with ethnic music.”

These stories fill the pages of Roque’s book, which compiles testimonies published along more than ten years for radio series broadcast by Radio Netherlands. The interviews reveal interesting aspects of the lives of the musicians and the surprising moment when they were brought to the world’s attention, just when it seemed the doors had definitely closed for them.

The book “How Cuba made the world dance” pays tribute to these musicians. In the words of Mirian Nunez Mas, who wrote the prologue, “This project was a project that served to promote Cuba around the world. We didn’t planned for it, and yet it is a reflection of our deepest authenticity. These rhythms, this perfect harmony, these voices, belong to the undeniable ambassadors of a Cuba of yesteryears, but also of today’s Cuba and of the Cuba of the future.”

Is Buena Vista Social Club a foreign album of Cuban music? Where did all these “aged youngsters” come from –as if they were trying to scare death away with their music? How did they become so famous internationally? What’s left of Buena Vista Social Club?

“I had been planning to write this book for a while now. It’s about the founders of Buena Vista Social Club, whom I met between 1999 and 2000. Following the announcement of the Adios Tour, I started to collect interviews. I interviewed all the members of the initial project for a radio series titled “The road to success,” which I produced for a radio station that does not exist anymore, Radio Netherlands. Then I improved the interviews, adding context information and more details obtained in further interviews that I conducted with some of the musicians.

What’s the book about?

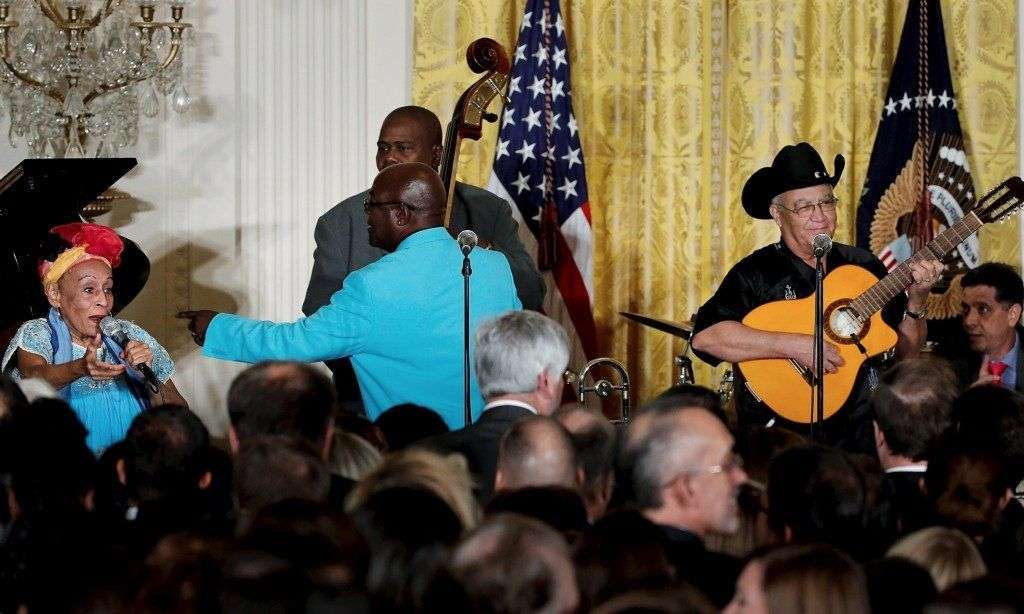

The book explores the dimension of the musical phenomenon BVSC was, 20 years into its creation. It tells the stories of the lives and work of the founders. I answer several questions in the book: Was it talent or was it chance what made this project become the most successful Cuban musical project abroad? Was there a strategy to make it become what it is today? Will the legend of the BVSC musicians find heirs 20 years later, new artists who make these sons and boleros live on outside Cuba? Why did this project which is so authentically Cuban almost go unnoticed in the country where it originated? How did El Cuarto de Tula become so famous that it reached the White House? Was it intentional or just luck?

What’s your personal impression of these musicians?

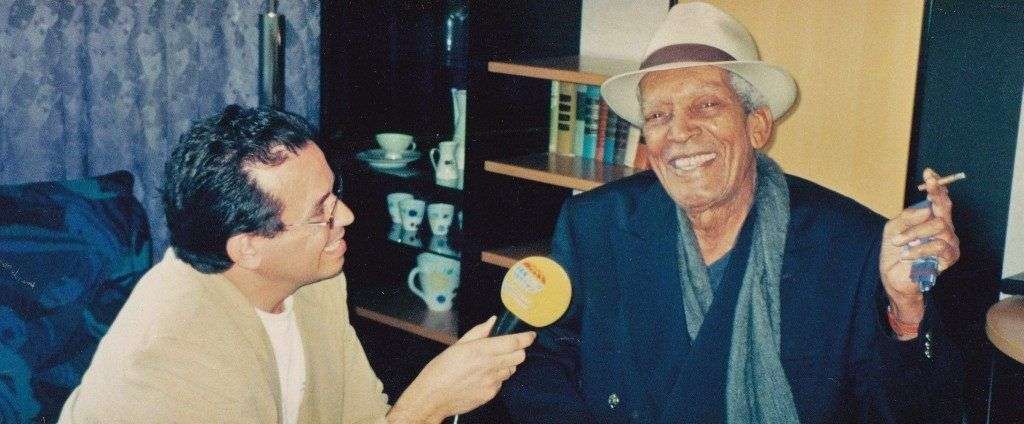

I sensed an enormous humbleness in my meetings with these talented musicians of BVSC. I will never forget the moment when Ibrahim Ferrer told me: “I don’t know how to talk about me.” I can still see Compay Segundo in front of me, sipping his coffee, smiling, and humming his Chan Chan. I remember Ruben Gonzalez’s kindness, sitting in front of me at the piano, playing his most famous compositions for me. Omara, telling me that she hoped to spend the rest of her live among smiles. All of them deeply impressed me, with their capacity to deal with fame without losing their authenticity as musicians with a commitment to their audience.