Forty years ago, Argentina was barely emerging from the shadows of a dictatorship that had left deep wounds and 30,000 missing.

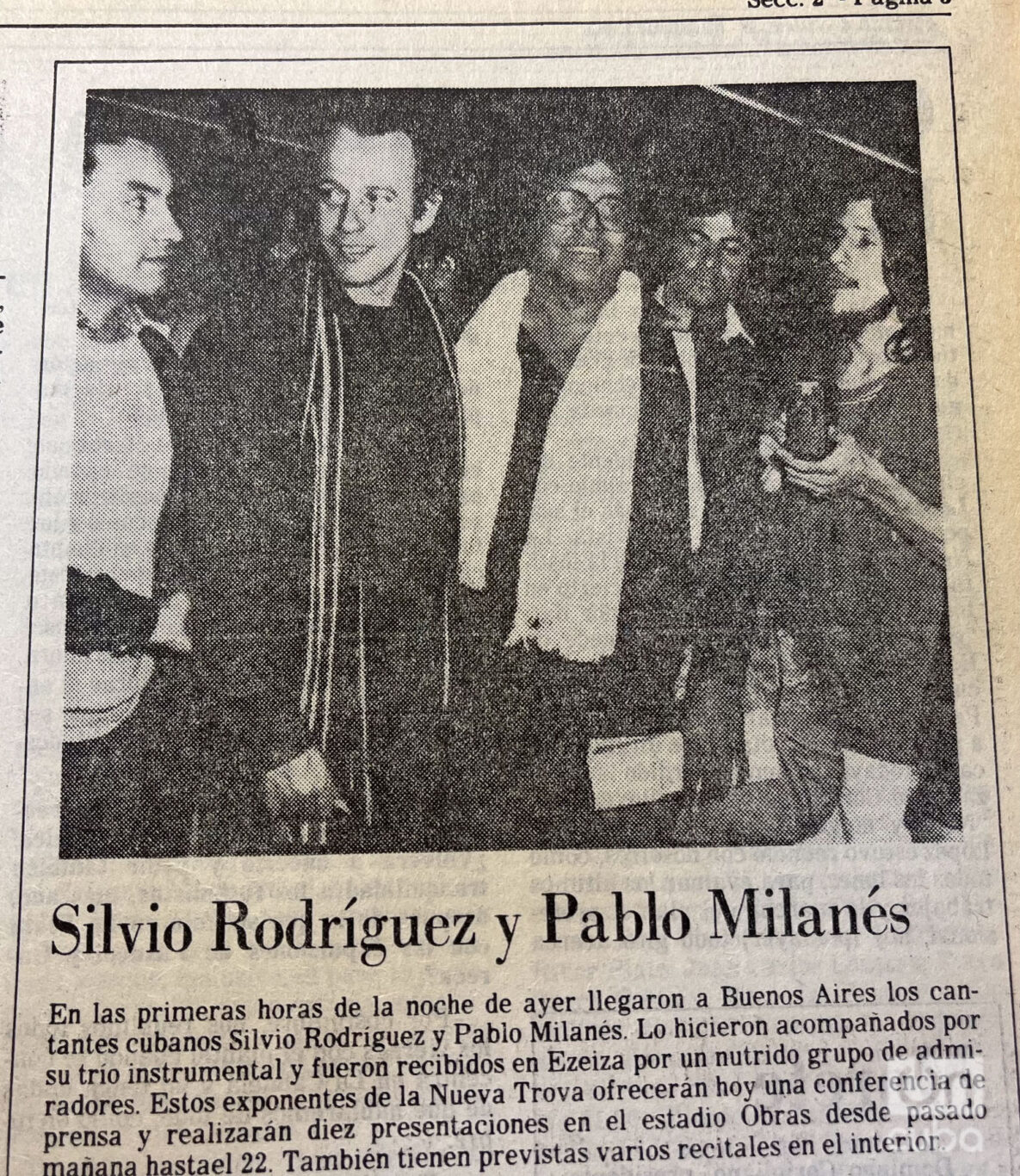

At that time, in the last days of March 1984, the city of Buenos Aires woke up wallpapered with posters announcing a series of concerts by Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés, two iconic names of the Cuban New Song Movement.

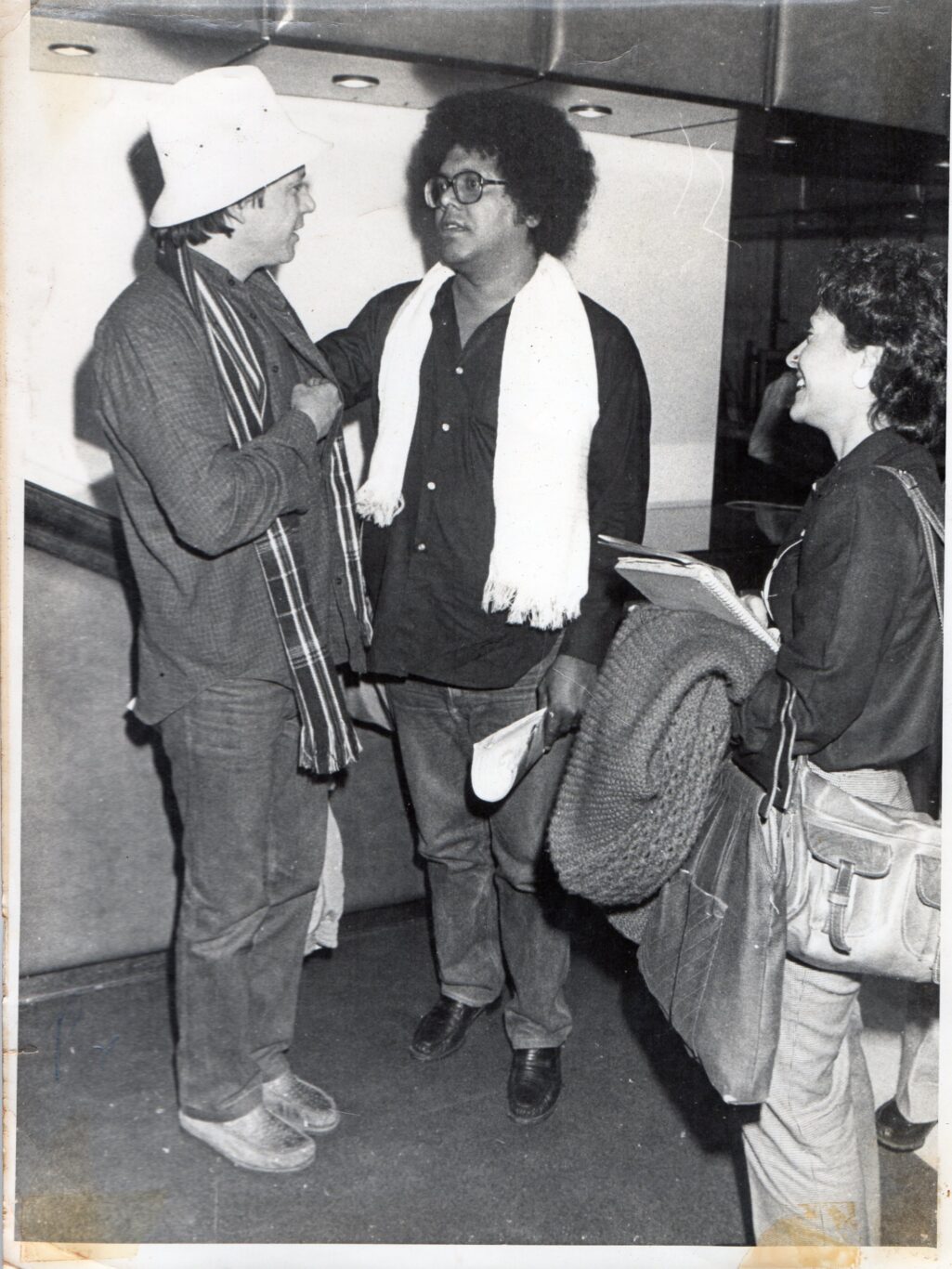

On April 2, 1984, the singers-songwriters set foot on Argentine soil. Silvio was 36 years old; Pablo, 39. The Cuban delegation was made up, among others, of musicians Frank Bejerano, Jorge Aragón, Eduardo Ramos and sound engineer Tony López.

They came from Quito, Ecuador, where they had performed on March 30 and 31 before 16,000 people. The night they landed at the Ezeiza international airport, a surprise awaited them: being greeted by hundreds of people with flags, posters and lots of music.

Journalist Sibila Camps was commissioned by the newspaper Clarín to cover the arrival. “Silvio and Pablo, more than a cultural event, in Argentina it was a social and even historical event of great magnitude,” I was told years later by Camps, who since then has not lost track of them.

The journalist keeps a relic from that night. It is a black and white photo taken by Carlos Roberto Bairo. Silvio, Pablo and Sibila appear in the snapshot, relaxed and smiling. The singers-songwriters do not look exhausted after the trip. Quite the opposite.

By then, Silvio and Pablo were already enjoying great popularity in several countries. Each one of them had held massive concerts in plazas in Mexico and Spain, for example. But Argentina was different.

“It was a very special circumstance,” Silvio told me about the subject. “When we arrived, they had just come out of the dictatorship. The next morning the first thing we had to do was go to the police. They took our fingerprints, photographed us, took our passport and gave us a document. That police mechanism still existed. It was a shocking reality. People saw a green Ford Falcon and started to tremble because they were the cars the police used to kidnap. It was a very critical situation. The feeling of oppression and persecution had not dissipated.

“I think that this situation of anguish, linked with joy and also with the disconcerting aspect of seeing two guys arrive from Cuba — and the Cuba of Fidel Castro — who sang songs that were prohibited…. I imagine that it must have been very revolutionary in the spirit, especially for the young people.

“We had a very strong and direct relationship with the reality of Latin America. We were very informed of what was happening. And those people, in a way, knew it too. There was a kind of dialogue…. Our arrival in Argentina was very intense for all those reasons.”

Forbidden melodies and voices

Although their songs were censored during the dictatorship, the voice of the singers-songwriters had transcended the imposed limits and borders. In Argentina, cassettes with songs by Silvio and Pablo circulated clandestinely from hand to hand.

These copies, generally poorly recorded, entered the country surreptitiously; many times through Argentine exiles returning from Spain and Mexico, where the first albums by Cubans as soloists were released and sold.

The Argentine journalist and researcher Víctor Pintos covered one of the concerts at Obras Sanitarias, Buenos Aires. It was a revealing experience to see and hear from their own voices the authors of hitherto persecuted songs.

“We Argentines learned the songs of Silvio Rodríguez and Pablo Milanés from cassettes that we obtained as best we could. As those were analog recordings, quality was lost in each copy. So if we played a seventh copy, let’s say, what we heard was basically a breath and behind it a voice with a guitar and a song that we didn’t always know the name of. Even less if it was a new or old song. Or what album it belonged to and what year it was published,” Pintos tells me.

They had to wait until 1983 to be able to acquire Silvio and Pablo’s records in Argentina, and without hiding, thanks to an agreement between the Polygram label and Egrem. In this way, Argentine editions of the albums Mujeres, Sueño con serpientes and Unicornio, by Silvio Rodríguez, were released; as well as Años, Comienzo y final de una verde mañana and Aniversario, by Pablo Milanés.

In 1982 Mercedes Sosa had returned from exile. For her reencounter with her public “La Negra” sang a dozen concerts at the Opera Theater in Buenos Aires. Among the repertoire of songs that she offered were “Años,” by Pablo Milanes and “Sueño con serpientes” by Silvio. Both songs were part of a double album titled Mercedes Sosa en Argentina, which went on sale in the middle of that year.

At the end of 1983, the Mercedes Sosa album opened with “La Maza” by Silvio and included a version of “Unicornio” arranged by Charly García, Argentine rock icon.

The songs by Silvio and Pablo in the voice of Mercedes Sosa quickly achieved great popularity not only in Argentina, but in the world. Over time they were part of the singer’s greatest hits.

At last in Argentina!

With such a background, it was not surprising that, when the arrival of Pablo Milanés and Silvio Rodríguez was announced in 1984, the tickets for the twenty concerts scheduled for the Argentine tour were sold out in the blink of an eye.

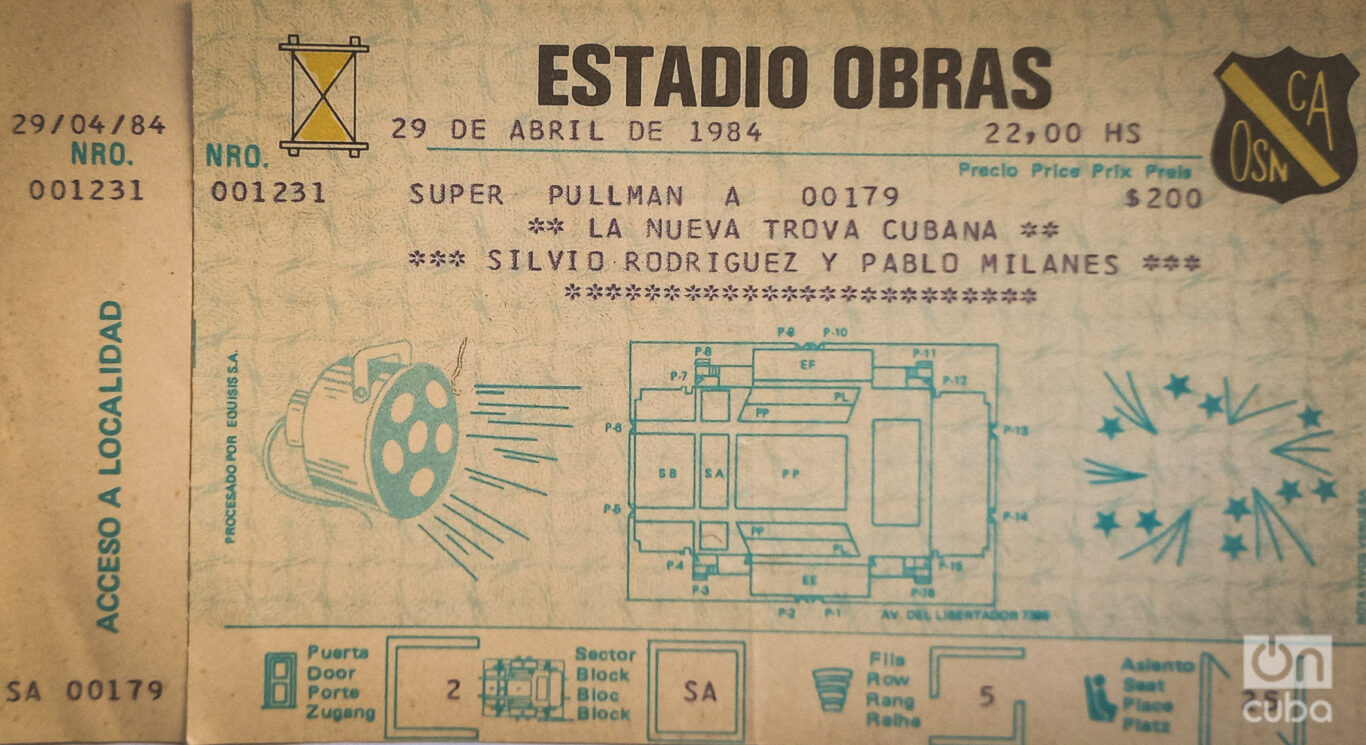

Silvia Salcedo was 20 years old at the time. Even today she keeps the ticket from April 29, when she attended the last of the concerts at Obras Sanitarias. Since that night, the piece of paper, now yellowed by the passage of time but very well preserved, represents for her a passage to one of the great moments of her life.

“When we found out that Pablo Milanés and Silvio Rodríguez were finally coming to Argentina, my partner and I did not hesitate to buy tickets for one of the concerts. The dictatorship had ended, our artists returned from exile and everything was bustle and euphoria. There was freedom to see, hear, sing and shout everything that we had been forced to keep quiet about for years,” she recalls.

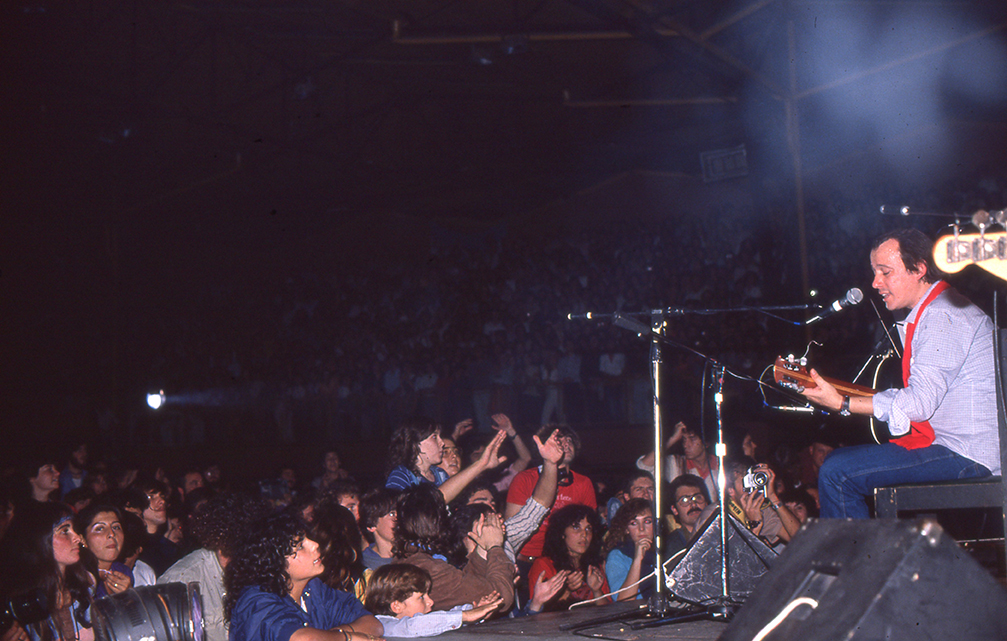

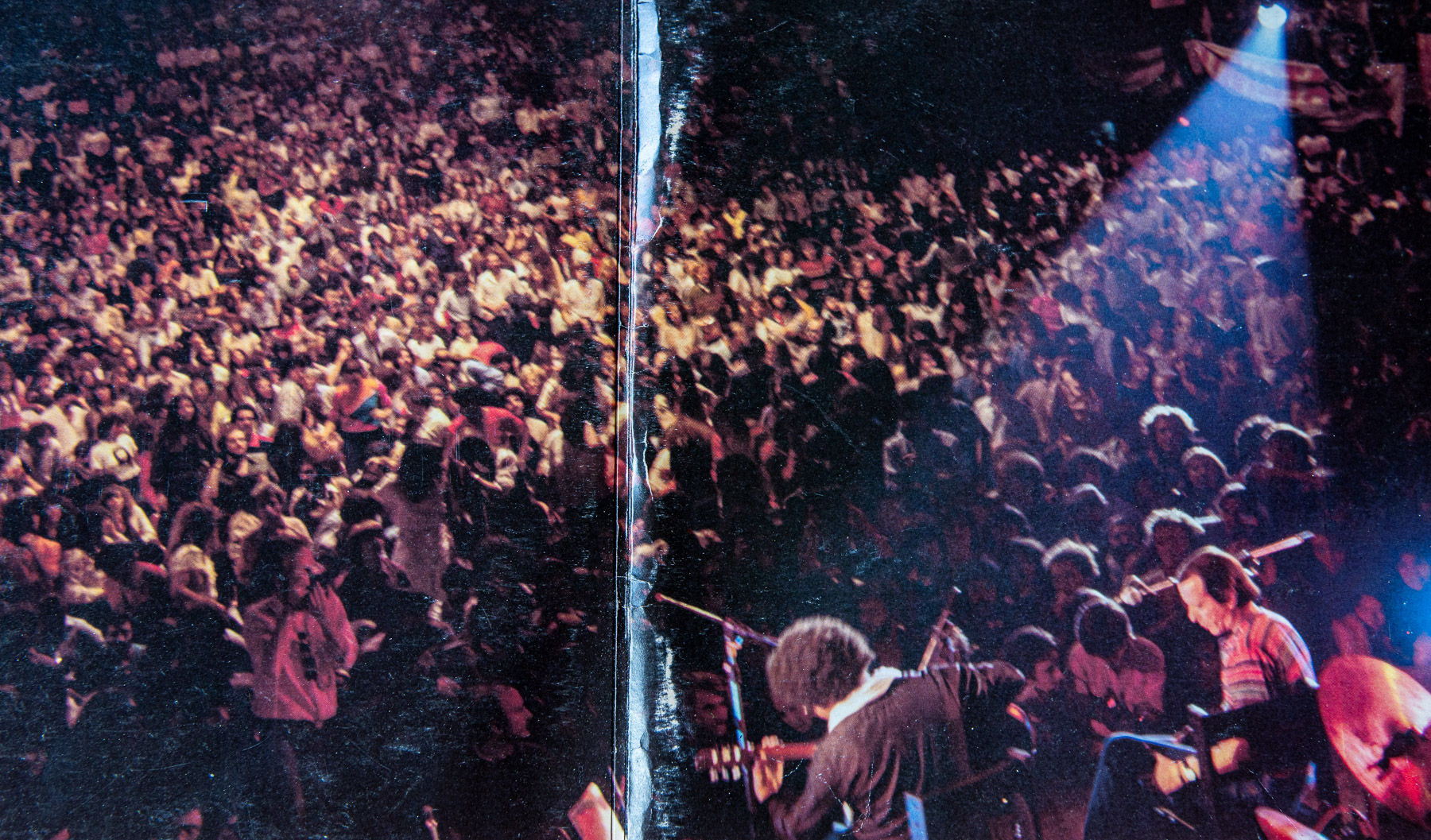

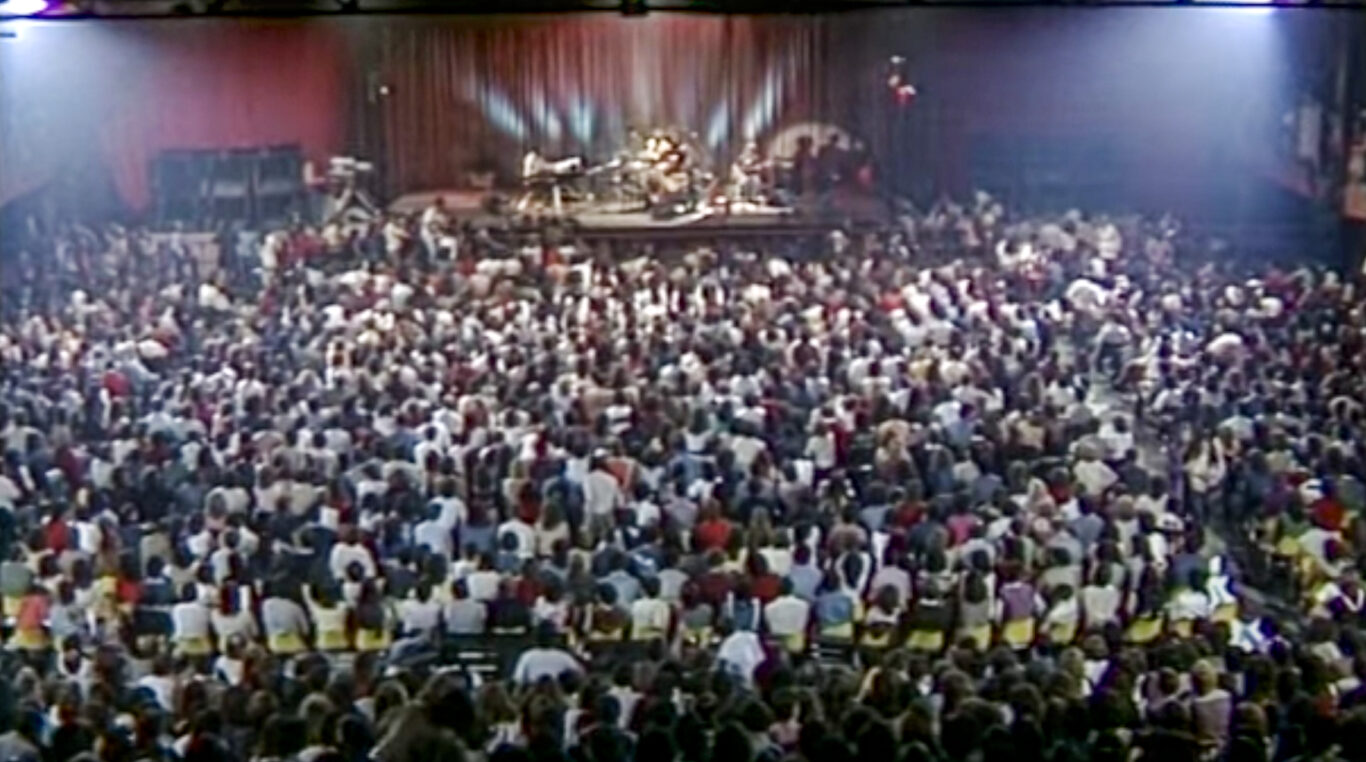

Fourteen of the presentations were held in Buenos Aires, at the famous Obras Sanitarias Stadium, with capacity for more than 4,500 spectators. The number of shows by the same artists set a record at the emblematic venue, known as the temple of rock in Argentina.

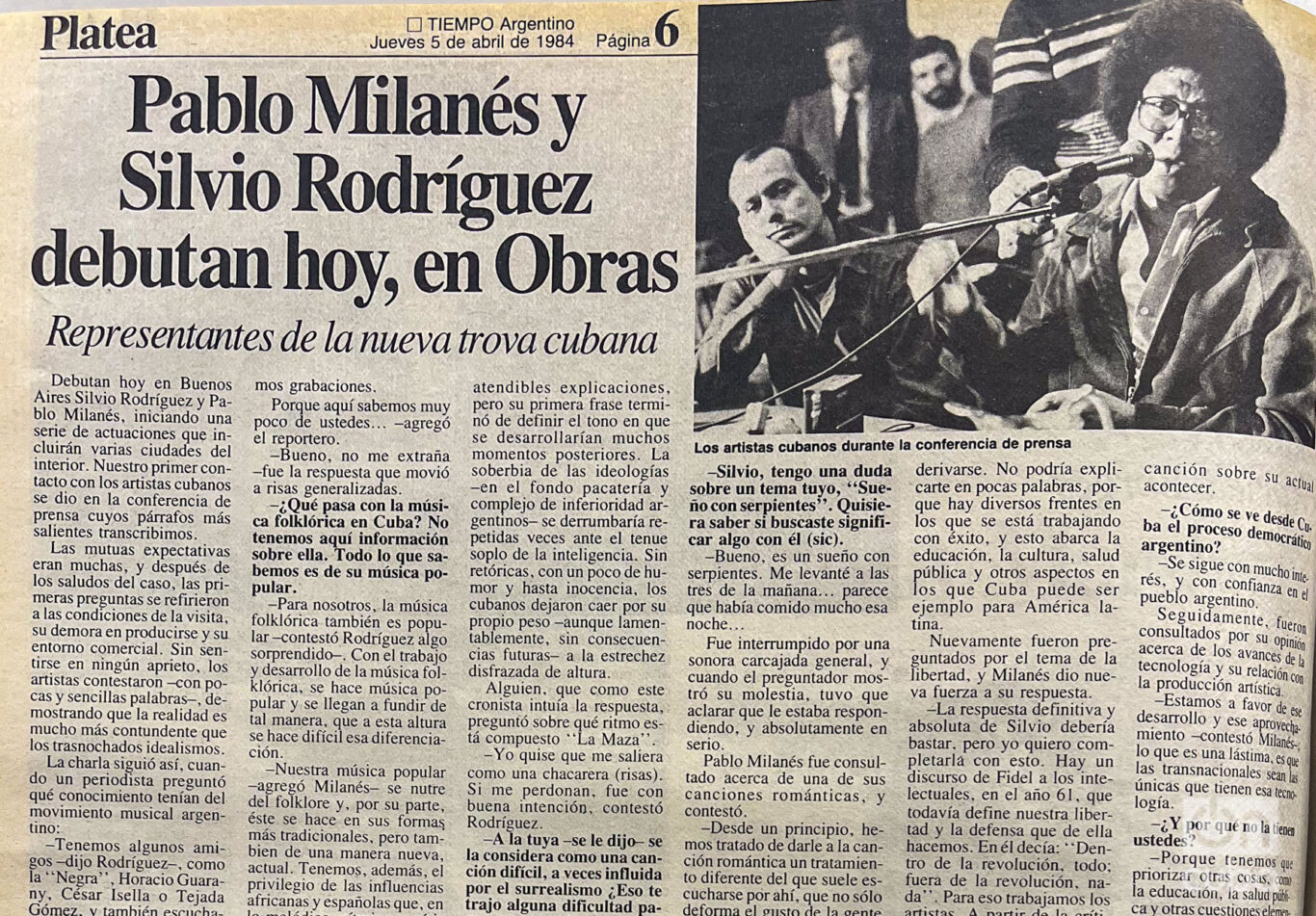

This is how the Cuban singers-songwriters debuted in Argentina, on Thursday, April 5, at 10:00 at night.

They were in the capital on April 5, 6, 7 and 8. From there they left for Córdoba, where they gave two concerts on the 10th and 11th. They returned to Obras Sanitarias on the 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th. They traveled again. On the 16th, city of La Plata, at the Gymnastics and Fencing Sports Center. On the 17th they landed in Santa Fe. On the 18th they touched down in Rosario. On the 19th in Mendoza and on the 21st in Tucumán. Up to that point it was the planned program.

However, given the demand, they returned to Obras, where they gave six more concerts. All of them to a full house. Between one presentation and another, Silvio and Pablo stayed in Argentina throughout April. It is estimated that more than 150,000 people saw them live and direct.

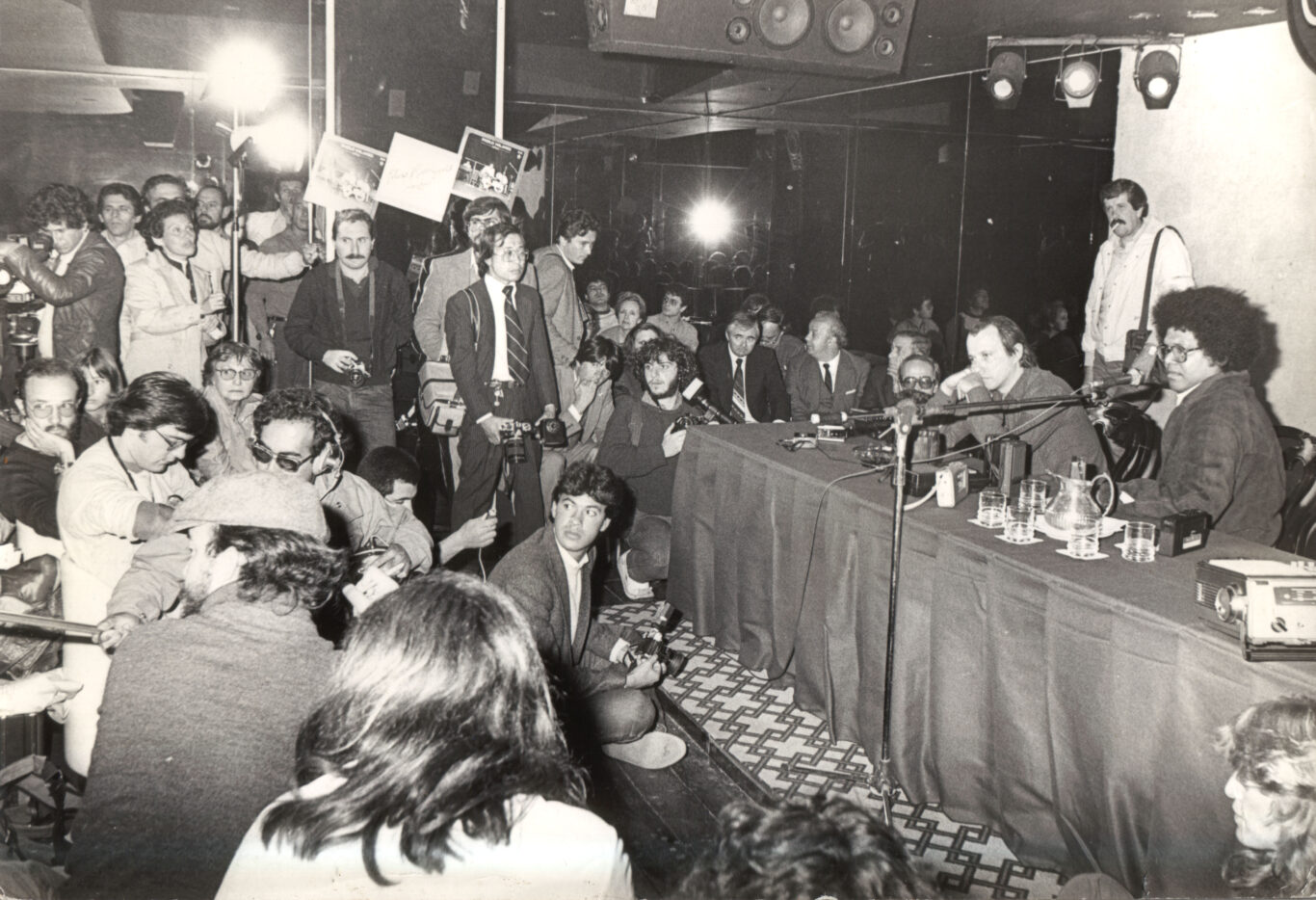

The expectation and emotion was so great that, before starting the series of concerts, a press conference had been organized. More than 150 journalists from national and foreign television, print and radio media, for almost 3 hours, asked about life in Cuba and its political system; freedom for artistic creation; the New Song Movement; how from the island they saw the process of recovering democracy in Argentina.

Part of that press conference appears in an extensive feature that Estela Bravo did for Cuban Television.

The U.S. filmmaker based on the island was in Buenos Aires filming ¿Quién soy yo?, a documentary about the struggle of the Plaza de Mayo Grandmothers in the search and recovery of the identity of boys and girls kidnapped by the military or under their control.

Bravo did not miss the opportunity to document the impact that Silvio and Pablo had in Argentina, with fragments of one of the concerts in Obras, and valuable testimonies from some attendees.

The guitar

Everything was ready for the long-awaited debut; or almost everything, since the guitar that had accompanied Silvio for so many years was broken during the trip. It was necessary to find a new one.

Although there were several musical instrument stores in the city, all references pointed to Miguel Ángel “Cacho” Onorato, owner of the Daiam music store, located on Talcahuano Street, in downtown Buenos Aires.

“Cacho” Onorato was very loved in the musical field, not only for having quality instruments, but also for his generosity.

Mercedes Onorato, daughter of Don Cacho, remembers every detail of that day when Silvio showed up looking for a guitar. In an exchange of messages, Mercedes kindly gave me details of the meeting.

“It was common for musicians to come every day to try guitars with nylon strings at our store. I remember hearing many of them perform chords of songs from the Cuban New Song Movement, such as ‘Sueño con serpientes,’ ‘Yolanda’ and ‘Años.’ Love for Silvio and Pablo was in the air, especially around their first concerts in Argentina in April 1984.

“At that time, many sheet music of all songs and musical genres were sold. In the store we had a large editorial section. And since the demand for Pablo and Silvio’s scores was high, all their scores were displayed in a prominent place.

“One day, while I was coming up from the warehouse in the basement of our store, I heard someone playing the chords of ‘Ojalá.’ The sound was different, it was not like the previous ones I had heard from other musicians. I hurried up the stairs and it was Silvio Rodríguez himself. I can’t describe my surprise and excitement. The beloved Negro Rada, Uruguayan musician, client and lifelong friend, had brought him to our business to buy a guitar with nylon strings.”

After a thorough test, Silvio chose a guitar and asked the price to pay for it. Mercedes went for a case for the instrument. At that moment, in a room alone with her father, speaking softly so that the visitors would not notice her, she proposed giving the guitar to Silvio. The great Cacho Onorato, smiling at his daughter’s excitement, winked at her and nodded.

“I showed Silvio how the chosen guitar looked in the best quality hard case we had, since I knew that after Argentina they would continue on tour and it was necessary to protect the instrument. Silvio insisted on knowing the total price to pay. That’s when we told him it was our gift and to please accept it. It was not a question of money, but a way to welcome him to a country that loved him and Pablo, loved Cuba.

“He thanked us and refused to accept such a gift. ‘No way. Thank you very much, but…,’ he said with absolute conviction and honesty. We insisted so much that, resigned and immensely grateful, he had no choice but to accept.”

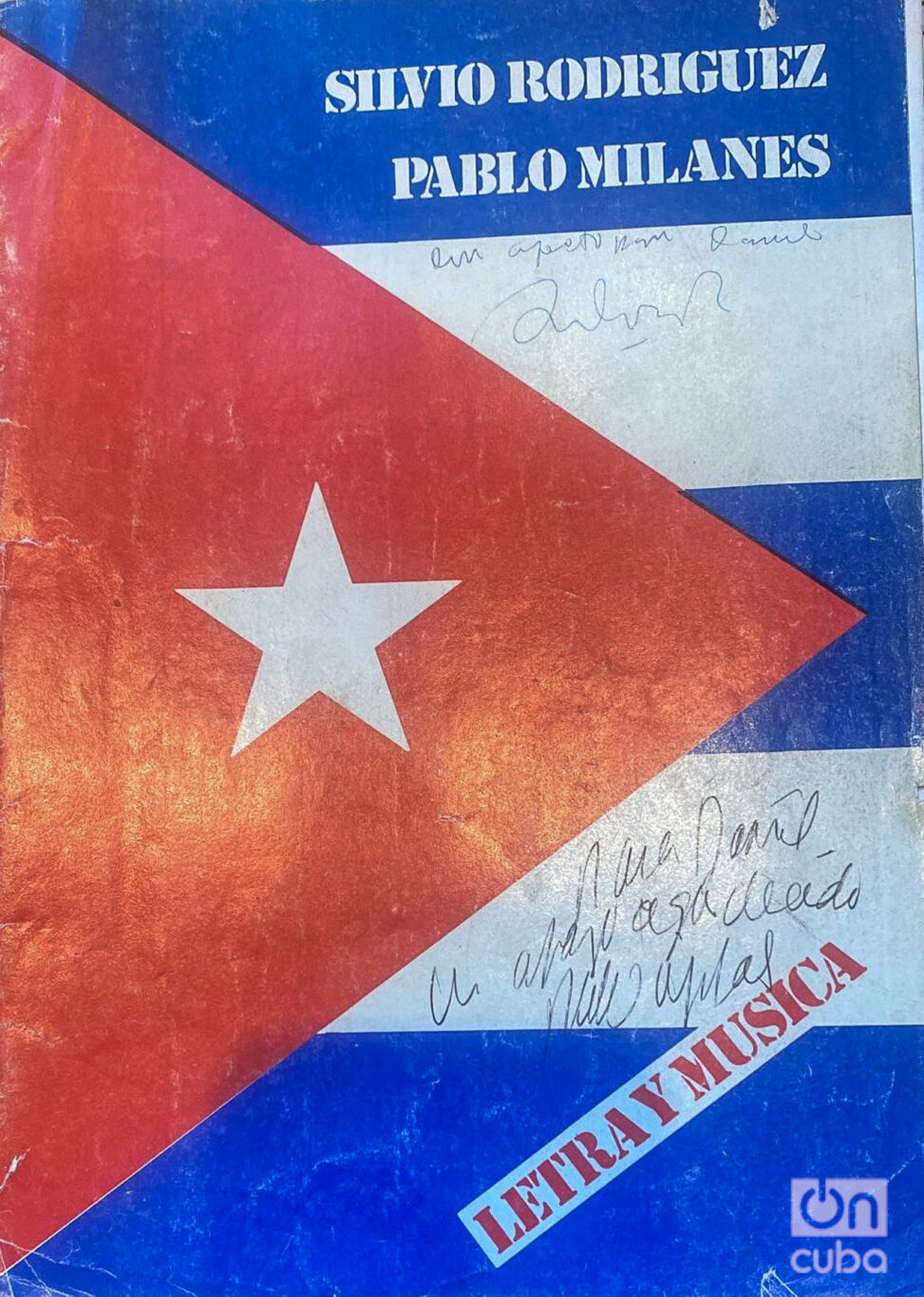

Before leaving, Silvio observed the large number of sheet music of his and Pablo’s songs that were for sale on one of the counters, Mercedes remembers.

“In a spontaneous gesture and of absolute generosity, he stopped, took a black indelible marker from his coat and began to suddenly sign I don’t remember how many of those sheet music with his songs. As he signed and signed, he told us with a mischievous smile: ‘Well, this is the least I can do. Let’s see if you can at least sell them more expensive.’ We all laughed a lot and said goodbye with a big hug.”

At the first concert at Obras, in one of the first rows of the stadium, Mercedes and Don Cacho enjoyed Pablo and Silvio, moved by those songs and that guitar that they knew so well. Mercedes also has the absolute record of having attended all the concerts scheduled in Buenos Aires.

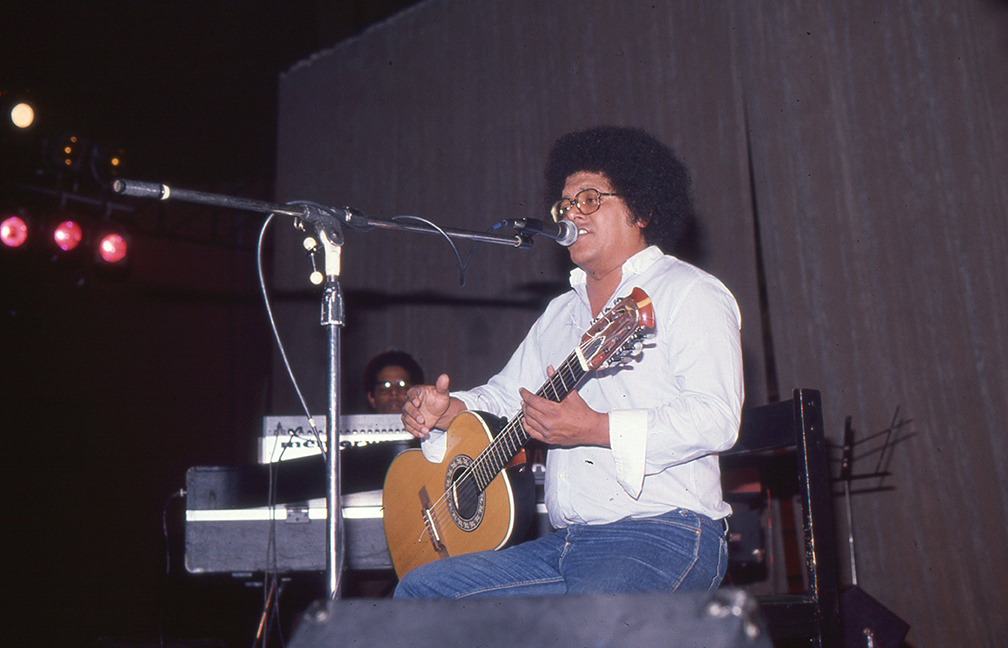

On stage

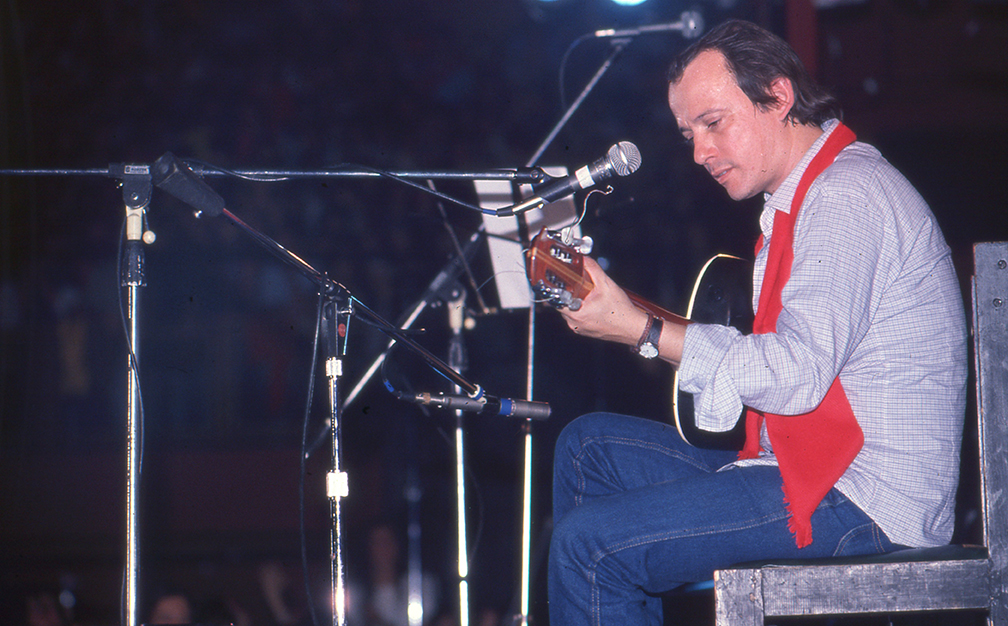

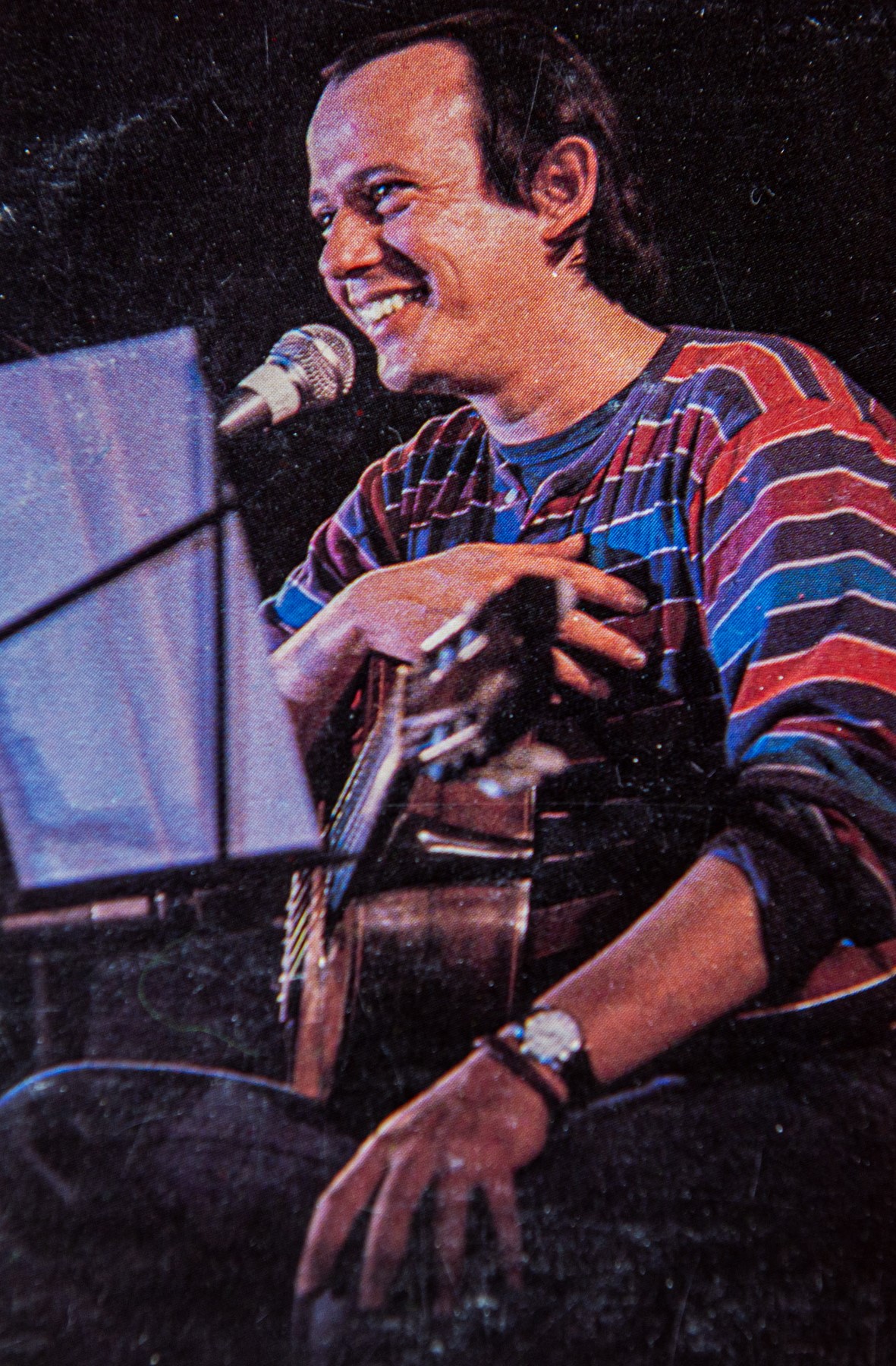

The concert program was organized as follows: Silvio, on guitar, was in charge of opening the first part. For an hour he would offer a bunch of songs; among which were “Por quien merece amor,” “Canción del elegido,” “El vigía,” “Ojalá,” “El tiempo está a favor de los pequeños,” “La maza,” “Unicornio” and “Te doy una canción.”

“That a solitary man with his guitar would generate a climate of attention, of silence around him, speaks of the expressive capacity not only of the performer but basically of his proposal. Silvio demonstrated in this way, singing at the extreme of simplicity, that what passes through the song is life, that you can play with your own objects, lyrics, music, arrangements and history,” Alejandro C. Tarruella published in Humor magazine after the first presentation.

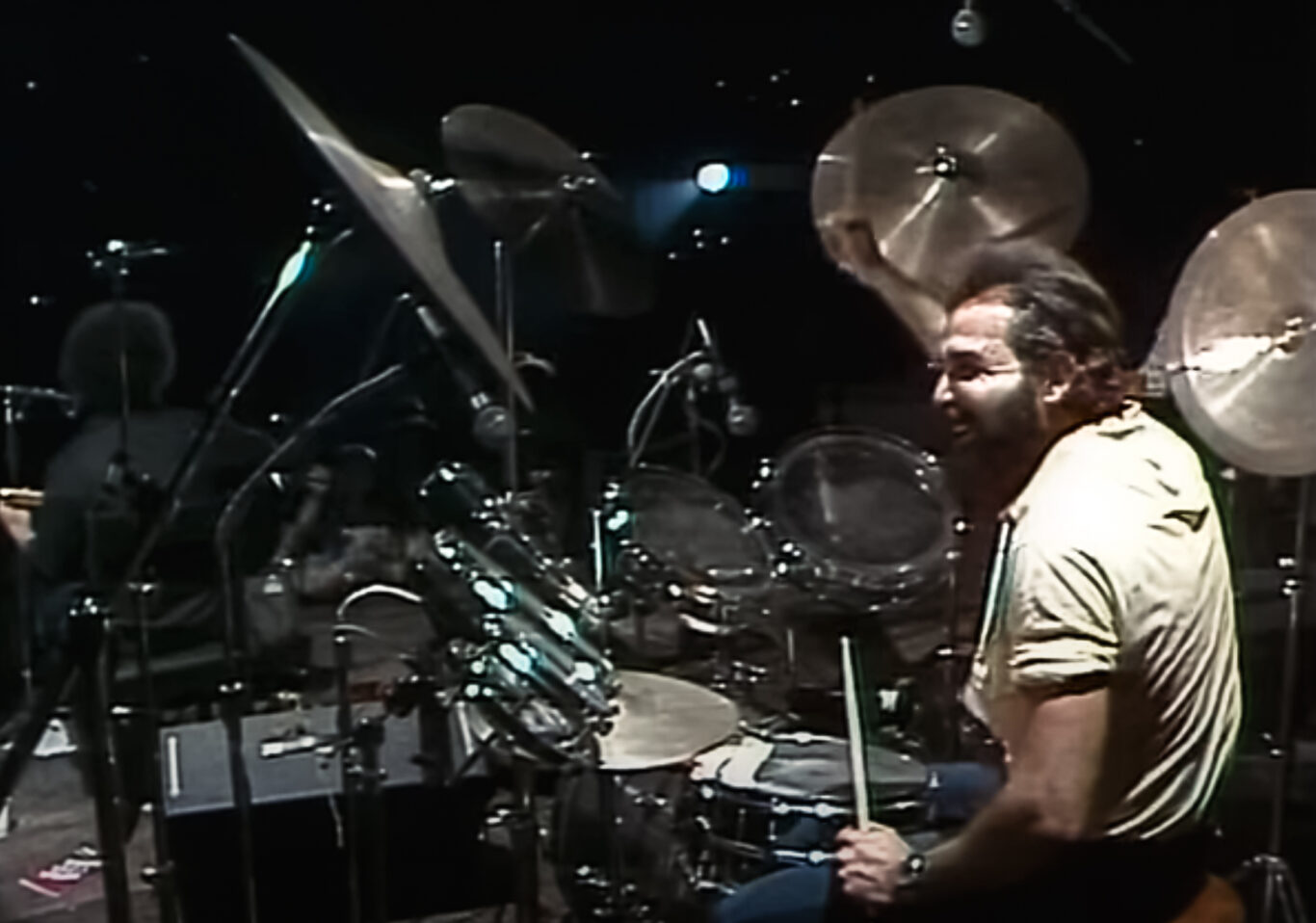

Then came Pablo, who was supported by the formidable trio composed of Frank Bejerano on drums, Jorge Aragón (father) on piano and backing vocals, and Eduardo Ramos on bass and vocals. His repertoire was composed of “Te quiero porque te quiero,” “Amor,” “Comienzo y final de una verde mañana,” “Años,” “Para vivir,” “Yo pisaré las calles nuevamente,” “La vida no vale nada” and “Yo no te pido.”

In that chronicle Tarruella said: “Pablo was a surprise. Not only his affable nature, his emotion every night (on one occasion he got up from his chair, went to the side of the stage and cried). Pablo illuminated the nights with his fresh spontaneity, with his popular songs that hit indifference.”

For the closing, a Silvio and Pablo duo accompanied by the band, sang nothing less than “Óleo de mujer con sombrero,” “Rabo de Nube,” “Yolanda” and “Hoy la vi.”

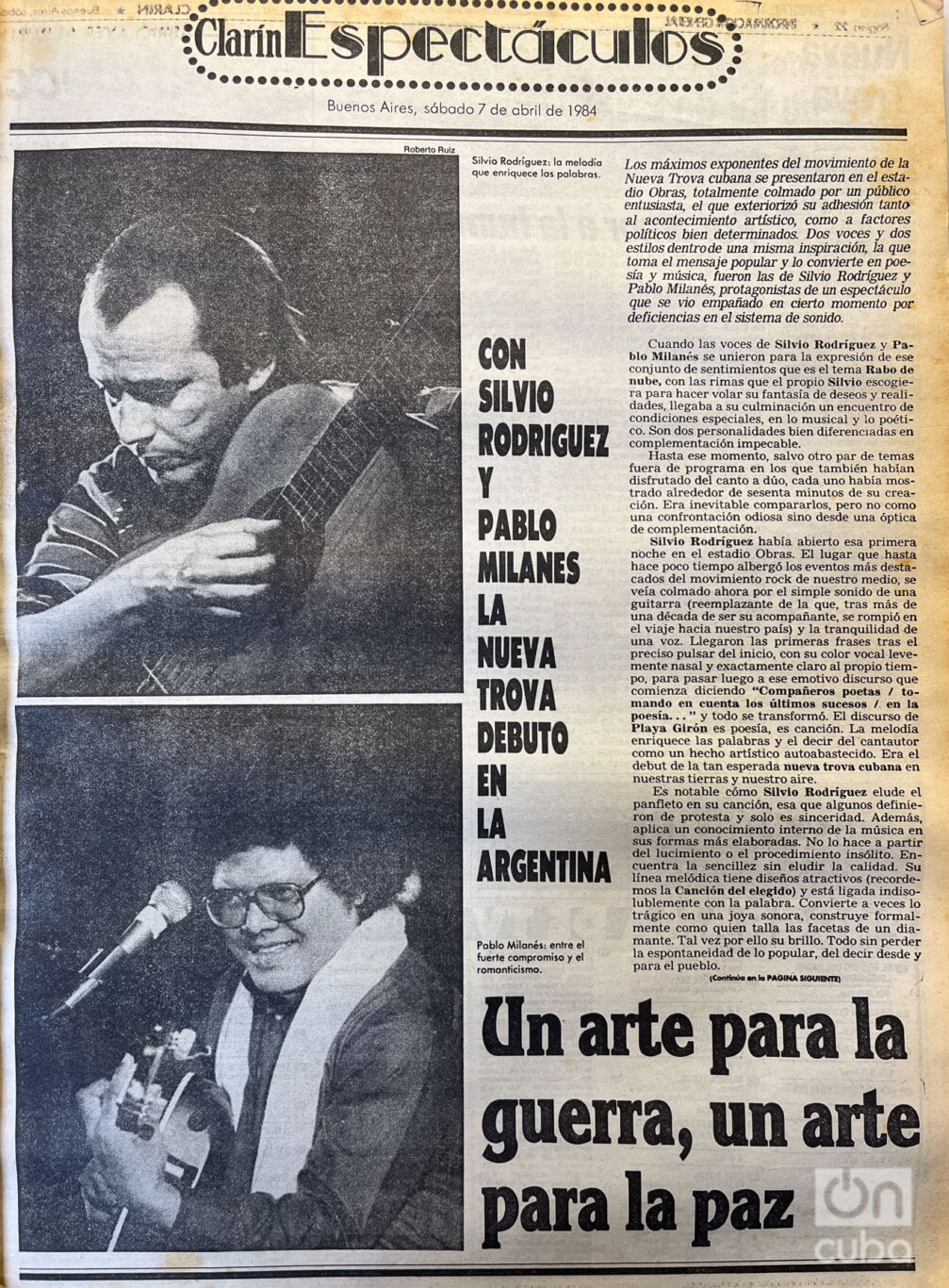

The first concert was full of emotions and also some headaches. According to press reports, the public entered the room even after the concert had begun and there were some sound problems. However, nothing overshadowed the night. In the article published in Clarín, reporter Sibila Camps noted:

“Unlike the majority of the authors of the new song movement of our continent, both Cubans have founded a new Latin American epic that is neither bronze nor marble, but earthly and palpable.”

For its part, the newspaper La Nación dedicated a good amount of space to reviewing what happened in Obras Sanitarias: “Silvio’s fantasy and talent create luminous images like rays, which always point towards quality.” It is said about Pablo that he “has an exceptional timbre and vibrato. He masters their impetus with a sense of proportion and good taste.”

Critics also praised the talent of the accompanying musicians. In the La Nación article you can read: “The trio is not something you hear every day…. Eduardo Ramos builds excellent supports for the harmony, in his bass, while Frank Bejerano’s drums have the salt of syncopation to the brim. But the person who exercises inventiveness most easily is the pianist Jorge Aragón. There is the outburst, the stilettos of rhythm, the oxygen that rescues from all tropical drowsiness.”

Those concerts were also impressive for the singers-songwriters. “What has happened here is incredible!” Pablo Milanés told journalist Alejandro C. Tarruella on the second night of presentations. In his article for Humor, Tarruella relates that the author of “Yolanda” was impressed by the great connection with the audience, who sang his songs even though it was the first time they were performed there.

Recordings

One of those concerts was recorded by Argentine public television and was broadcast days later. It is estimated that around 8 million viewers across the country watched it.

Thanks to the existence of this material, we can enjoy truly special moments of the concert and witness over time how the fervor of the audience weaves an emotional connection with the artists. At the same time, it puts before our eyes the complicity between Silvio and Pablo on stage, especially when they come together to sing “Óleo de mujer con sombrero” and “Yolanda.”

And as life and history go in circles, in “Oleo de mujer con sombrero,” Jorge Aragón Oropesa stands out on the piano with sublime phrasing in a crucial moment of the song. Thirty-one years later, in 2015, Silvio presented his album Amoríos in Argentina. Among the songs that make up the album is a new recording of the song (as part of the original tetralogy). The person who recorded the piano for the album and played at its launch in gaucho lands is Jorge Aragón Brito, son of that musical genius who accompanied Silvio and Pablo on their visit to Argentina in 1984.

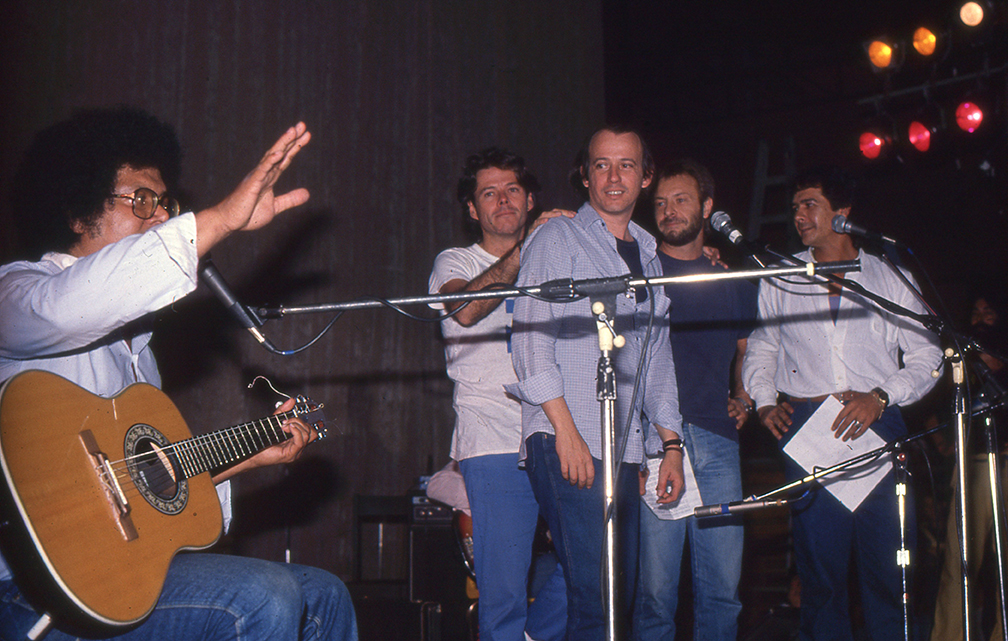

Another milestone of 1984 happened in the third concert at Obras, on April 7, when the Cubans invited Argentine colleagues to share the stage. The invitation was repeated in one of the last shows. León Gieco, Víctor Heredia, Piero, César Isella, Antonio Tarragó Ros and the Zupay Quartet paraded. Some of them, like Gieco and Heredia, had been exiled and banned during the military dictatorship.

There is a beautiful photo, taken a few minutes before going on stage, in which Gieco, Silvio, Heredia and Pablo are seen in the dressing room.

Victor Heredia has it framed and hanging in his house, where he received me to talk about that event.

“The year 1983 passed with a lot of anxiety and, suddenly, the extraordinary possibility of having Silvio and Pablo in Argentina arose. It was finalized in April 1984 and they came under a law that, if I remember correctly, had emanated from the dictatorship. The regulation said that any foreigner who arrived from a communist country had to present himself to the police and certify that he was not going to generate or commit any insurrectional act. Crazy! I was part of the musicians’ union and we were immediately against it.

“Silvio and Pablo,” continues the singer-songwriter, “surprised several Argentine singers with the proposal to unite our voices with theirs. Imagine, we immediately said yes. We knew their songs by heart. I proposed to Silvio to sing one of his and he replied: ‘No, brother, let’s sing one of yours. Todavía cantamos, it makes a lot of sense.’”

Pablo did the same with León Gieco, with whom he performed “Canción para Carito.” So everyone locked themselves in a room at the hotel where the Cubans were staying in the center of Buenos Aires and began rehearsing for the concert they would give a few hours later.

“They had an established repertoire,” recalls Heredia, “with a concept of the concert already determined and, for the moment, they broke with all that to incorporate not only the Argentine colleagues but also the repertoire of the Argentine colleagues. It was a great gesture that spoke of the beauty and sensitivity of Silvio and Pablo, in addition to what great artists they are.”

Famous albums

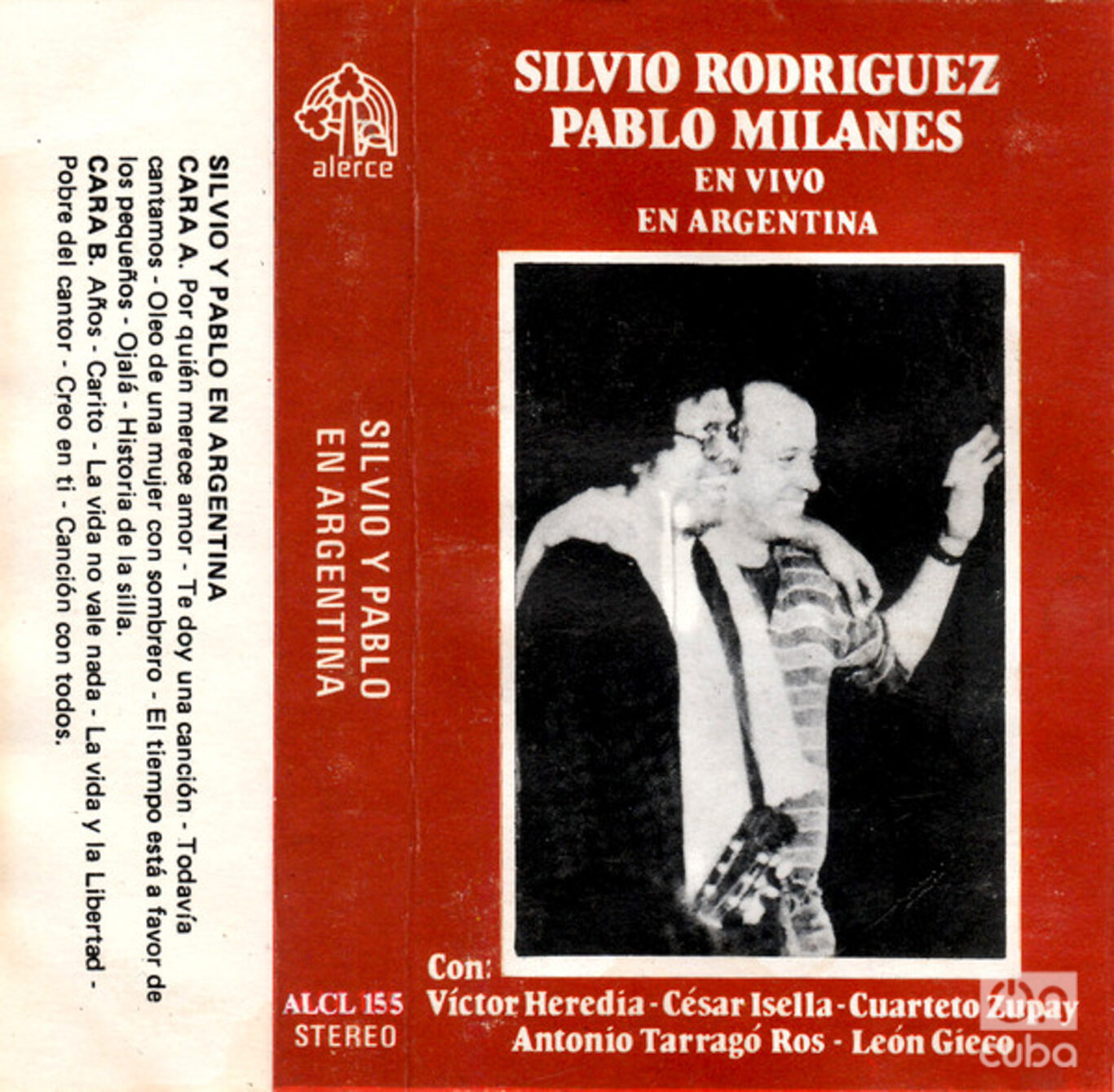

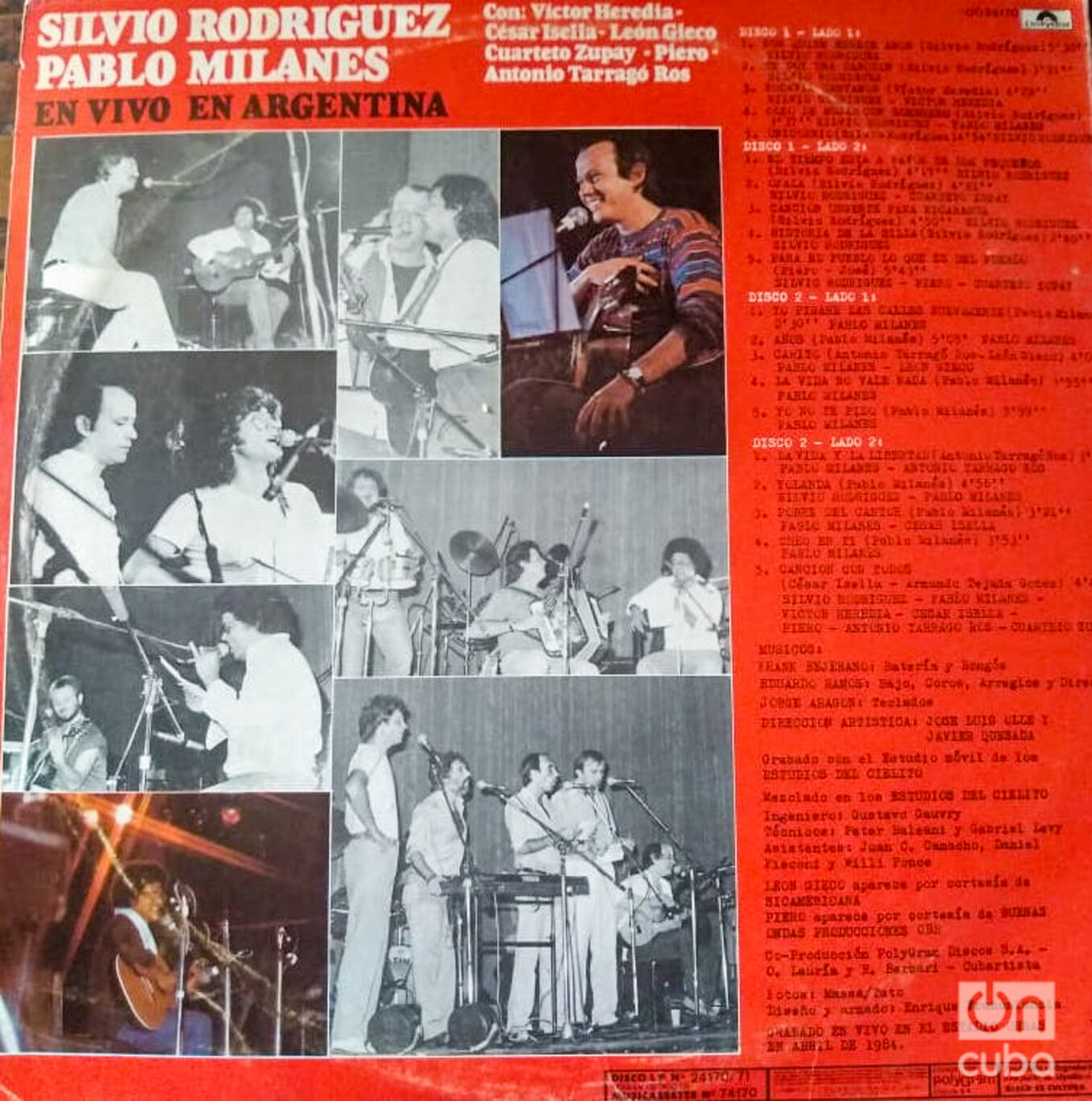

That concert was recorded by Estudios del Cielito. Its owner, sound engineer Gustavo Gauvry, was in charge of mixing a double LP titled Silvio Rodríguez – Pablo Milanés: En vivo en Argentina, a few months later, under the Polydor label.

The album was a resounding sales success. It crossed the Andes Mountains and the Alerce label published it in Chile. It also sailed to the other side of the Río de La Plata to find a version in Uruguay with the Orfeo label.

For months, Silvio and Pablo’s songs remained among the top favorites among Argentines. In August 1984, the Centro Cultural del Disco in Buenos Aires published a national ranking in which the Cubans’ album shared the podium among the most listened to along with Thriller, by Michael Jackson, and Can’t Slow Down, by Lionel Richie.

Given the success of the album, in 1985, they released volume 2, also in vinyl format, with some of the songs that had not been included in the first edition. This phonogram, by Silvio, is made up of the songs “Playa Girón,” “Canción del elegido,” “Pequeña serenata diurna,” “El vigía” and “Llover sobre mojado.” From Pablo there are “Amor,” “Comienzo y final de una verde mañana,” “Amo esta isla” and “Yo me quedo.”

The recordings became famous. The well-known vinyl records were published on cassette and, in the 1990s, on CD. In 2008, under the Lucio Alfiz Producciones label and distributed by the multinational Sony BMG, a two-CD reissue appeared with remastered sound, unpublished photos taken by Antonio Massa (author of the cover photo of that first LP), the lyrics of the songs and two songs that had not been included in any of the previous albums: “El tiempo está a favor de los pequeños,” by Silvio Rodríguez and “Acto de fe (Creo en ti),” by Pablo Milanés.

From those first encounters between the singers-songwriters and the Argentine public an echo remained that still resonates through generations, despite the passage of time.

Silvia Salcedo remembers it with awe. “I experienced that concert as an indescribable delirium. Tears flowed from emotion. It was like I was breathing again after a horrible period. Suddenly, everything lit up. Forty years after that concert, I remember it with nostalgia. At that time we again were idealists, we believed that the dark times would not return; but today, in the present, I see that it was not enough; that the ideals of social justice we dreamed of did not fully materialize. Luckily, we have the songs left.”

Silvio and Pablo’s first concerts in Argentina, four decades ago today, were a milestone that transcended songs, albums and videos. Those nights in April 1984 became a testimony and catalyst of a new era for a country that was beginning to experience freedom, when the horror that it had just left behind and that would mark its history forever was still hot on its heels.