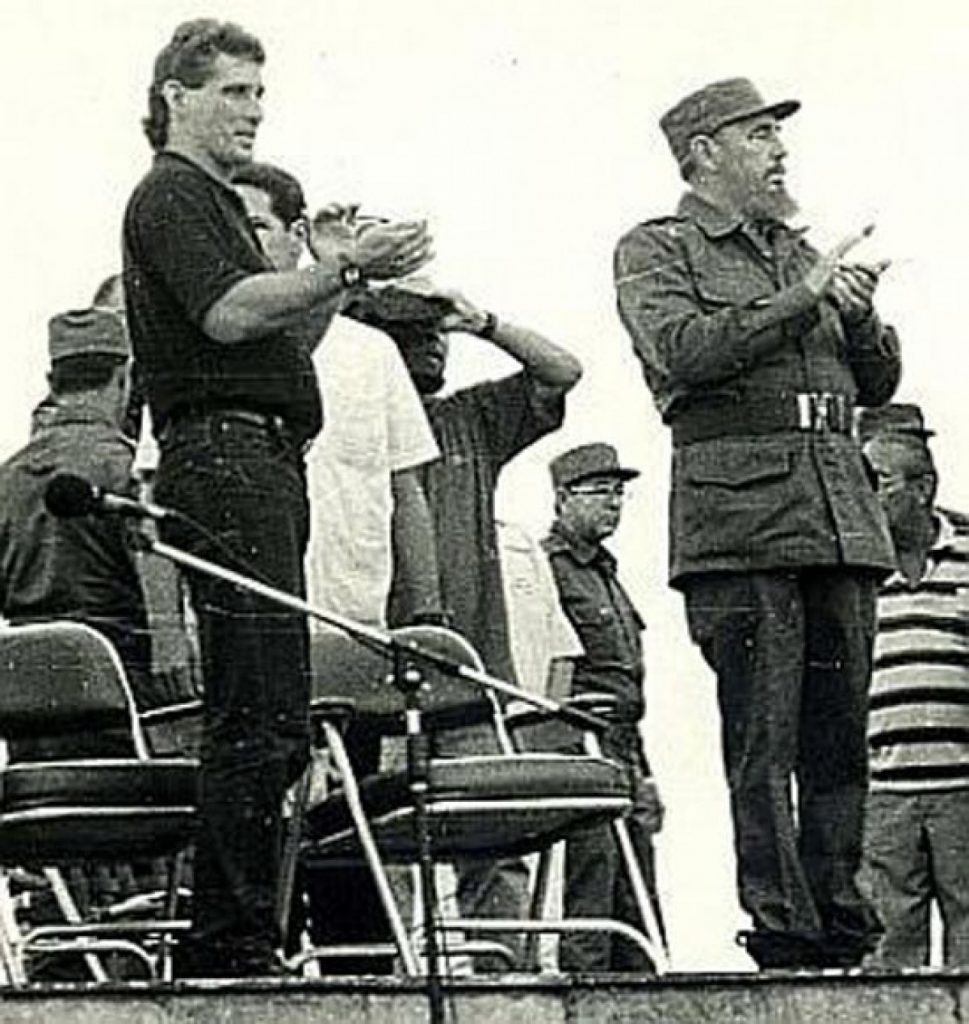

He was a young, long-haired slim official who used to ride his bike greeting neighbors and because of his personal style of leading his province he was as popular as a local rock star.

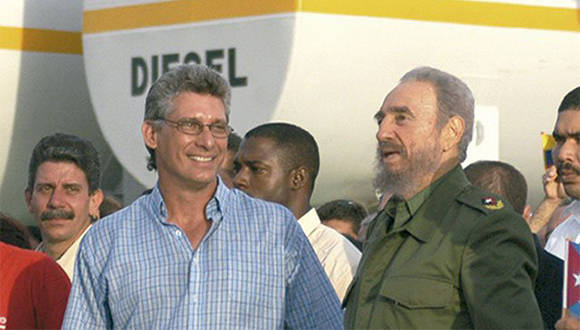

A decade went by since then and Miguel Díaz-Canel – who will now possibly succeed President Raúl Castro in Cuba’s presidency – looks like someone else, another person: grey haired, serious, thrifty with words and with scarce public visibility.

Díaz-Canel, who is currently the first vice president, has a short official biography of personal and professional details, and although no one knows for certain how he will project himself in his government, there are some signs of what will possibly be a new style.

In a country where there doesn’t exist the figure of first lady and the leaders – who usually move in the midst of important security operatives – zealously hide their private life, Díaz-Canel arrived almost without guards last March at a voting center in Santa Clara, some 300 kilometers east of the capital, where several foreign media were waiting.

The official walked along one block, holding his wife’s hand, while he greeted the persons who approached him.

“Here we are building a government and people relationship,” he said during that unusual public appearance before the cameras to vote for the parliament. After voting he returned to Havana, but leaving a message: a new type of leadership could arrive, with a continuity of the revolutionary process, but with a renovation of the forms.

Díaz-Canel, 57, must face a stagnated economy, an infrastructure in decadence, the hostility of the United States that did not lift the embargo nor the sanctions against the island, and the criticisms of a model of state control with low wages in the framework of a cooling of private enterprise.

Many Cubans across the island barely know him. The last years of his political ascent have gone by slowly but without pause, step by step, and he assumed such a low profile that months would go by without knowing about his activities.

He barely jumped into international limelight last year when he was the protagonist of a leaked video in which he championed closing independent media and labeled European embassies as an advance of the subversion against the Revolution.

However, that orthodox image contrasts with many of his Villa Clara province fellow citizens’ perception of a simple, tolerant, friendly but demanding man, the province in which he spent his childhood, youth and of which he was first secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC) for nine years, a post which in practice is more important than that of the local head of government.

“He used to stroll through the park with his girlfriend. They were in school. They were some 15 years old,” says Hilda Alegre, a hairdresser who remembers him as the slim young man who used to go out in couples to stroll like others during those years in the 1970s.

When he graduated as an electronic engineer from the University of Villa Clara in 1982 he did his compulsory military service until 1985. In 1987 he joined the Union of Young Communists and started working as a professor while he traveled to Nicaragua as part of a delegation supporting Sandinismo.

In those times he liked The Beatles – stigmatized by the Revolution as representatives of capitalist decadence – and the theater.

In 1994 he was appointed as first secretary of the PCC in Villa Clara and he rapidly won a reputation for being a working official with a modest style and whom the neighbors remember as the first of his rank to not move to a larger home.

“The house where his mother lives is in an awful state, even the plaster has come off. His brother also lived there. He didn’t fix the house to live more comfortably,” commented Fermín Roberto Tagle Suárez, 78 and who used to do the guard duty rounds, usual among neighbors, with Díaz-Canel.

“He always found out about the real problems the people had. And he also demanded, if he were soft he wouldn’t have gotten where he is now,” said Suárez.

By 1996 in the middle of a harsh economic crisis derived from the fall of the Soviet Union which shook Cuban families and overwhelmed them with shortages, Díaz-Canel was already the father of two children from his marriage with dentist Marta Villanueva, his longtime sweetheart.

He was popular and strikingly young for his post and he even saw to all those who knocked at his door in the Party venue and his own home.

“When he got home he would throw his briefcase and run off to do his guard duty. Some comrades didn’t want to assign him guard duty because he came home from work tormented, but he would say: I am a citizen of this country and I do guard duty just like any other person,” Liliana Pérez, whose home is in front of the one in which Díaz-Canel lived with his wife and children, commented to AP.

The house – today painted yellow and red – belonged to the family of his wife before she, divorced, moved to Havana with the children.

A sort of legend was born then around Díaz-Canel: the politician then started to make surprise tours to verify the service that the people received and it is said – although no one was able to pertinently confirm it – he appeared wearing a costume in places where the public was attended.

The journalist of the local CMHW radio station, Xiomara Rodríguez, witnessed this.

“He carried out an intense work of communication with the people,” she said. “For example, in 1996 when he had recently become first secretary he came to this space (‘Alta Tensión’ of the local radio station) which is an opinion program about the most burning issues. Two hours with live open microphone, receiving calls from the population.”

Presenting himself live and spontaneously speaking with the people was something unusual for Cuban officials. Even at present they don’t have a public activities agenda.

Rodríguez remembers one of those surprise tours that Díaz-Canel began in the morgue, continued with a funeral parlor and then to the cemetery to confirm how the state services were working on such a sensitive issue for families as a death.

Moreover, he was interested in culture and was respectful of diversity.

Under his protection in Santa Clara El Menjunje flourished, the first cultural center that presented shows of transsexuals and openly worked with the gay and alternative community like rockers and he even took his children to the children’s activities of the place. Today two of them form part of a music band called Polaroid.

In 2003 Díaz-Canel was transferred from Villa Clara by the PCC as first secretary to the neighboring province of Holguín, some 700 kilometers to the east of the capital. His work there lasted until 2009 and was not so special.

A tour by AP through this city showed that although the neighbors appreciate some works like a crosswalk in the very center or cafeterias and entertainment places, they criticize him and consider he was not at the height of his fame.

“In my opinion one shouldn’t spend so much on boulevards and parks when there are people in marginal barrios living very badly,” affirmed Anahí Tamayo. It’s not only about fixing up the center, what the people (foreigners) see when they come, but rather the surrounding areas.”

Some Cubans from the place indicated that the years Díaz-Canel spent in Holguín were also very marked by a strong drought that affected the agricultural markets and domestic supply, the budget was very small, the regionalisms and prejudices made him be seen as a stranger and his charisma was unable to catch on.

In the personal aspect, his passage through Holguín left him a new wife: Liz Cuesta Peraza, the woman who accompanied him in March to vote.

In May 2009, Díaz-Canel arrived for the first time to a post in the national sphere when Raúl Castro appointed him minister of higher education.

Under him, the study plans were adjusted, their contents were modernized, the postgraduate regulations were modified and the use of technologies of the higher studies schools was boosted with computer labs and the digitalization of contents. He was also one of the first officials to appear with a laptop at meetings in a country where the Internet in homes is restricted and prices are very high.

In 2012 he became vice president and months later with the elections first vice president and he was no longer seen in the streets or in the media.

According to diplomats and analysts, the transformation of his style was due to the logic of recent history in the country’s leadership, in which the revolutionary generation took out of the race the younger people accusing them of not being sufficiently loyal to the process.

Precisely in 2012, Harold Cárdenas was a professor of Marxism in the University of Matanzas and together with another two friends began a blog called “La Joven Cuba,” which had a clearly left-wing profile although it criticized several aspects on the island. This is why orthodox sectors of the PCC and the local government accused them of “playing into the hands” of Cuba’s enemies and they were blocked, but without them requesting it Díaz Canel defended them.

“Díaz-Canel sat with the three of us and said ‘what do you need to continue making La Joven Cuba?’” Cárdenas recalled in a recent interview with AP. A while later his blog returned to normalcy, and until now they are a debate forum that not always agrees with the government policies.

For Cárdenas, Díaz-Canel’s intervention demonstrated that the new generation – subsequent to the revolution and before his own – will give continuity to the process, but will change according to its vital experiences: the fall of the socialist camp and the subsidies, the failures of the dogmas of the 1970s communism or the need for respect for a greater religious and social diversity.

“Díaz-Canel has been in a very uncomfortable position for years, no one from his generation has survived to get to the place where he is,” said Cárdenas. “I talk to Díaz-Canel as if it were with an uncle. He is much more communicative than what he shows…. There’s a grey image of Díaz-Canel that is a government construction of depriving the leadership of colors to show an unnecessary solemnity,” he considers.

Andrea Rodríguez and Michael Weissenstein / AP / OnCuba

Read all of OnCuba’s coverage on the subject:

que circo