From the coasts of far-off Africa and in subhuman conditions, they were taken to Cuba in the bellies of the slave ships: men, women and children. Unknowingly, the Spanish slave traders transplanted what we now call religious syncretism, because they were not just bringing the official Catholic saints on those ships; they were also transporting traditions, customs, psychology, music, religions, ceremonies, legends and orishas (gods) along with the people they had tragically snatched from African lands. Today, they are an inseparable part of our Cuban nationality.

One of these orishas was Yemayá, a goddess from the region of Oyó and Abeokuta, in Nupe, Africa, who is considered to be the mother of life and of the other orishas. She controls all bodies of water, and her maximum representation is the sea, the fundamental source of life. She symbolizes the beginnings and the dynamics of life; renovation and purification are her divine properties. Protector against all illnesses relating to the womb and those involving harm or death by fresh or salt water, rain or humidity.

According to one of the legends, at the beginning of time, there was only fire and burning rocks here on Earth. Then Olofi the Almighty decided the world should exist; he turned the smoke from the flames into clouds, sending down the rain that extinguished the fire, and he lay Yemayá down among the enormous holes in the rocks to draw veins in the earth so that life would propagate. Lying there in all of her immensity and clothed in solitude, Yemayá exclaimed, “Ibí bayán odu mi: My womb hurts,” and from within her were born the rivers, the orishas, and everything that breathes and lives on the earth.

In Cuba, Yemayá is syncretized with the Virgin of Regla, patron saint of the bay and port of Havana. The story goes that back in 1690, in the hamlet of Regla, located on the land of the Guaicamar sugar mill, a hut was built that held a painted image of the Virgin of La Regla de San Agustín (the Order of St. Augustine). Two years later, the hut was destroyed by a storm and subsequently, Juan Martín de Coyendo, a pious and humble man, decided to build with his own hands (and the financial help of Don Alonso Sánchez Cabello, a Havana merchant) a stone chapel that was completed in 1664. At that time, a new statue of the Virgin had arrived in Havana, brought by Sgt. Major Don Pedro de Aranda. She was placed in the chapel and was worshipped. On December 23, 1714, the Virgin was proclaimed patron saint of Havana Bay and her feast days became a tradition that was very popular among all social classes. Whites, nobles and black slaves — who were free for a few days — drank aguardiente (sugar-cane liquor) and watched cockfights and spontaneous bullfights. Joyful carols to sweet María rang through the air, but also the beat of batá drums, invoking Yemayá the powerful, the other mother. For Cubans, this syncretism is natural, because the Virgin is the mother of God, dressed in blue and white, and her chapel stands on the shores of Regla; to worship her, her followers from African-based religions must cross the ocean, the home of Yemayá, the powerful mother, merciful queen of the sea.

For many researchers, Yemayá has many caminos, or ways, and these ways of complexity and richness refer to the many divisions in the personality of this orishas. Some of these are: Yemayá Awoyó, the silver-haired one who stays at the lake; Yemayá Akuara, who lives between two waters, in the river’s convergence, protector of the sick; Yemayá Okuté, ruler of the corals and mother-of-pearl, who appears on the reefs and is the bearer of Olokun (the ocean); Yemayá Asesú, Olokun’s messenger, who lives in stormy waters but tends to show herself when the waves break; Yemayá Mayalewo, who lives in the indigo-blue deep sea, where the seven ocean currents converge, and in the entrance to the bay; Yemayá Okotó, who is in the reddish-bottomed coastal waters, where the seashells are, and who presides over naval battles; Yemayá Ibú Akinomi, who lives on the crests of the waves, and who makes the world tremble when she is angry; Yemayá Konlá, who is foam, who builds and who lives in the propellers of boats; Yemayá Ibú Ilowo, ruler of the money that is in the sea; Yemayá Oggún Ayipo, who lives on the sand, has large breasts and causes mature women to give birth; Yemayá Oggún Asomi, who lives on the sea’s surface, and is very fond of the swamps; Yemayá Ibú Gunle, mother of Ondina (the whale), who is represented by the ocean sediment on the reefs; Yemayá Ibu Tinibú, who is the rough seas that are worshipped; Yemayá Ashaba, who is called the ship’s captain, the master of boats, and who is considered “the greatest of the female saints, because she gave life to all creatures, which are born and die like the moon; Yemayá Ataremawa, who is the master of the treasures of the sea; Yemayá Ibu Agana, who lives in the depths of the ocean, in the chasms among the reefs, not on the surface, and who is the Yemayá that makes it rain.

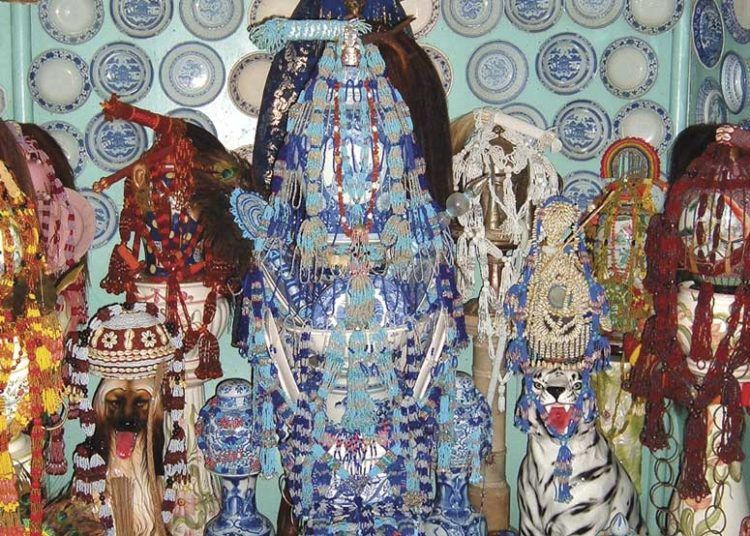

In Cuban homes, Yemayá lives in a white soup tureen, large earthenware jar or white receptacle that is painted blue, which holds her attributes and tools. On the receptacle, her children sometimes place the seven intertwined handles or her crown. Her attributes include a full moon (procreation), an anchor (hope), two oars (destiny), a boat (protection) and a key (authority) made of silver, steel, tin or lead; an agogó, acheré or maraca, which is used to call her and worship her, and a hand fan with mother-of-pearl and gold slats, decorated with beads and sea shells as a symbol of her royalty. All of these attributes are decorated with ducks fish, nets, stars, seahorses, shells and everything that relates to the sea, in miniature.

They say that Yemayá has a character that is indomitable, avenging, astute, protective and very hard-working. Her children are affectionate, strong-willed, strong and rigorous; sometimes they are impetuous and arrogant. They like to test their friends; they resent offenses and never forget them, although they do forgive them. They love luxury and magnificence. They are just, although somewhat formalistic, because they have an innate sense of hierarchy. Yemayá´s name should not be pronounced by her worshippers without first venerating her by touching the ground with their fingertips and kissing the trace of dust on them; and before entering the sea, her domain, her children should cross themselves, so that she will protect them and shelter them in the immensity of her power.

I just want to mention I am just new to blogging and site-building and actually enjoyed you’re blog. Almost certainly I’m going to bookmark your site . You definitely come with fabulous stories. Thanks a lot for revealing your web-site.