OnCuba recommends this text by Abigail Jones, published in Newsweek

Traveling from Miami to Havana is a haphazard, seemingly nonsensical process that requires patience, guile, humor and a ruthless willingness to cut lines. Thankfully, I’m traveling with Alberto Magnan, so we skip the airport check-in line because he knows a guy. Magnan, who’s 53, was born in Cuba, left at the age of 7 and, aside from a short stay in Spain, has been living in New York City ever since. He and his wife, Dara Metz, are behind the Magnan Metzart gallery in Chelsea, where they focus on international artists, particularly Cubans. Ninety minutes before our flight takes off, we breeze past the folks who started lining up two hours ago, and head straight for the ticket counter, where he greets a woman who is clearly in charge of something. She takes my passport, then disappears. Magnan tells me not to worry.

While we wait, he introduces me to Mark Elias, president of Havana Air. He says long lines have been “the norm” for years for charter flights between Miami and Cuba. Most flights “require three or four different check-in positions to finally get your boarding pass,” Elias says, adding with a bit of pride, “but we check the flights differently. We check a flight in an hour and a half.”

Thankfully, the woman who took my passport reappears about 20 minutes later. She hands me a rectangular folder, and inside I find my boarding pass, my return ticket, my passport and a brochure about Cuba. Tucked all the way in the back is a pale blue piece of paper that looks like trash. “Don’t lose it,” she says.

“What happens if I do?”

She and Magnan say, almost in unison, “Don’t.”

Less than an hour after we take off, we land in Havana. As soon as the wheels touch down, the pilot comes on the intercom: “If you’re happy to be in Havana, clap!” The plane sounds like my apartment did when the New England Patriots won the Super Bowl in February (I’m from Boston).

By the time Magnan and I drop our bags at the hotel and eat dinner, it’s evening. We’ve hired a driver, a thin, 50-year-old man named Raphael. He is a trained physician, but he quit medicine after four years to start his taxi business. He drops us off at the mouth of Plaza de San Francisco de Asis in Old Havana, and before we walk 15 feet, half a dozen taxistas converge on us. Need a ride? Americano? Where to? I shake my head no and keep walking toward the vast cobblestone square, which is lit up with floodlights and packed with people.

Day and night, tourists flock here for the historical sites and architecture. Across the street is Havana’s seafront boulevard, the Malecón, teeming with young people, day or night. In a country where many earn in a month less than what it costs to eat at a paladar (a privately owned restaurant, as compared with the dominant state-run restaurants, where the government funds the eating establishment and makes decisions about management and wages), the Malecón gives locals something to do. We walk through the plaza, down a ways and into a modest lobby. There’s a security guard at the door and, just inside, a woman sitting behind a desk. Magnan speaks to her in Spanish. I have no idea what he says (I speak high school French), but he’s clearly persuasive, because eventually she nods. We’re in.

Magnan, a few of his friends and I pile into the tiny elevator. Someone asks him a question about the event, but Magnan silently shakes his head and points to the ceiling. His message is clear: They’re listening. We all shut up and wait for the doors to open.

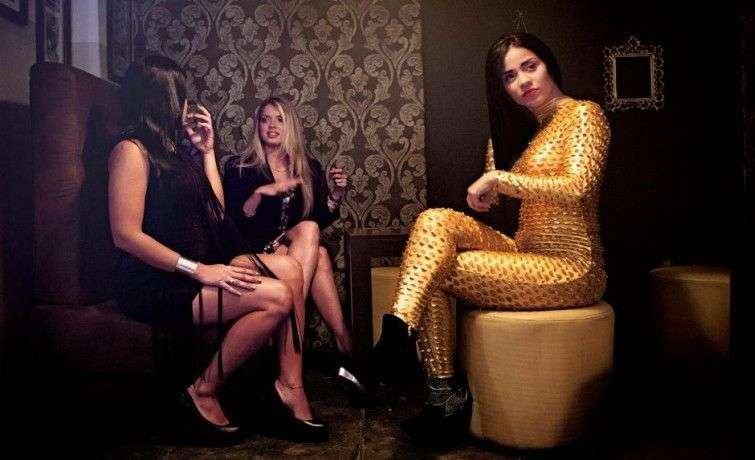

When they do, we are on the roof-deck of a two-story penthouse apartment overlooking Old Havana. The scene looks as if it’s been airlifted from a high-end Miami hotel: sleek white chairs and couches, delicate flower arrangements, a full bar. Off to one side, a film is being projected onto the facade of a nearby building.

Half an hour later, guests start disappearing inside, so I follow—down a spiral staircase until I reach a living room so vast and opulent I feel as if I’m on the set of a Leonardo DiCaprio period drama. A large hammock of thick velvet hangs from the ceiling. The floors are covered in ornate rugs. Oversized plants rise up against the walls studded with sconces and artwork. Nearby, equally ornate rooms hold a pool table and a robust dinner buffet. Down the hall is the most pristine bathroom I’ll see during my week in Havana. Perched on a ledge near the shower is a fat statue of…yes, those are penises.

Everyone here is dressed—older women in gowns, young models in tight dresses, men in sharp suits and hats and shiny shoes. It’s as if age—and Communism—doesn’t exist here; older guests mingle with the younger set, and not a single person is looking at a smartphone. I am surrounded by Cuba’s intellectual and cultural elite. I meet Cucu Diamantes, the Grammy-nominated Cuban-American singer and actress, and her husband, Andrés Levin, a Venezuelan-born and Juilliard-trained American record producer and filmmaker who won a Grammy in 2009 for the In the Heights cast album. He spearheaded the inaugural TEDxHabana last November. Together, he and Diamantes founded the fusion band Yerba Buena, which earned a Grammy nomination for its 2003 debut album. Levin points out some famous Cuban actors and musicians. There are even a few members of the Castro family. A cloud of cigarette and cigar smoke envelops us all.

The U.S. embargo, which began in the early 1960s, prohibited American investment in Cuba. Art, books and music, however, were exempt, giving artists the leeway to earn their money and travel outside the country, albeit under the watchful eye of the government. In a country where there are neither real estate tycoons nor hedge fund moguls, artists and intellectuals are among the 1 percent!

This is not the Havana most tourists see; nor is it the Havana most Cubans know. Even writing about it seems like something the Cuban government wouldn’t approve of, because, well, viva la revolución, right?

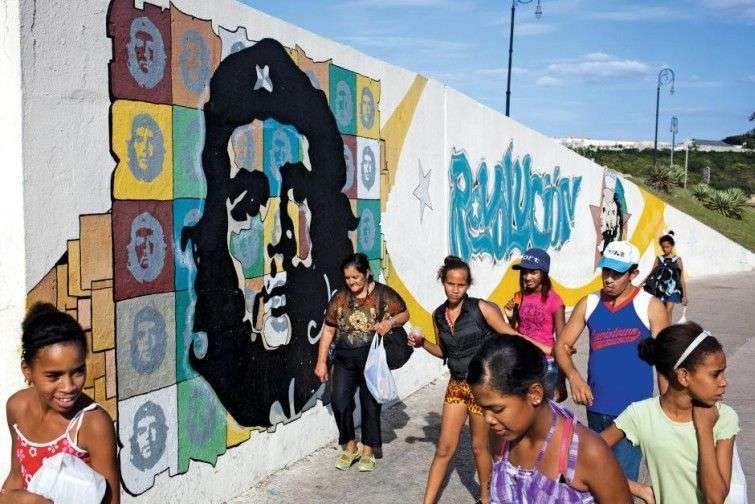

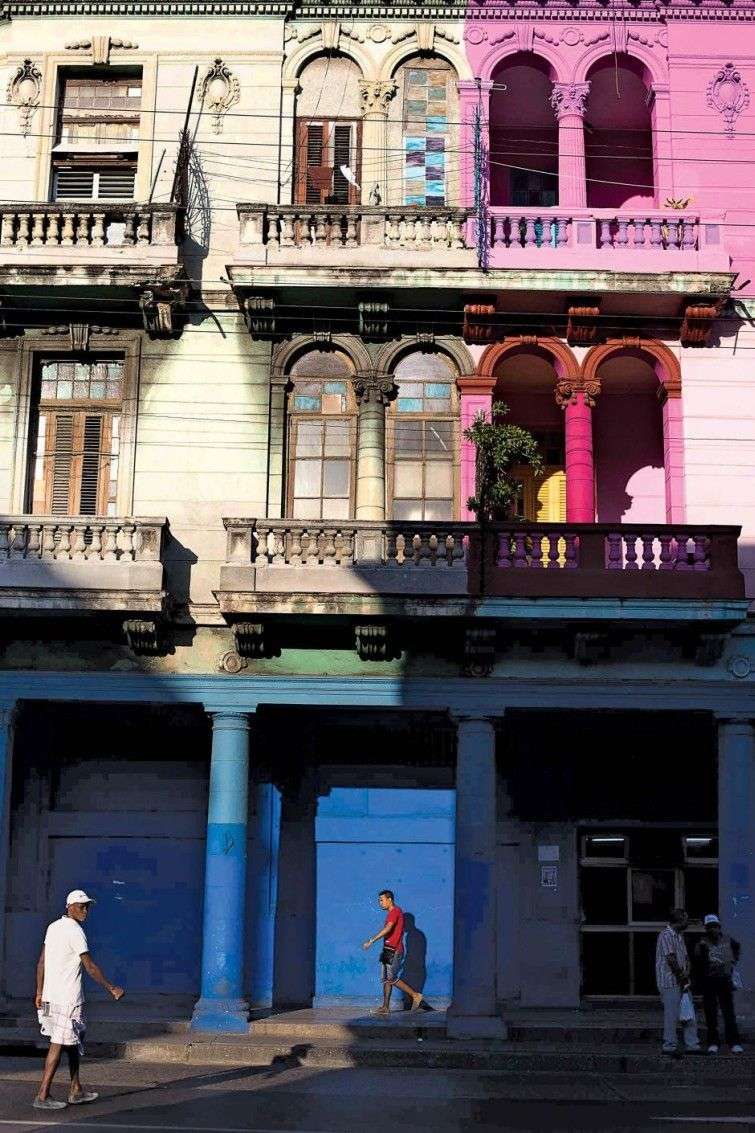

For the rest of my time in Cuba, I see the Havana you probably see in your mind: The vintage Chevy convertibles with rusted tail fins; the propaganda posters that read “La Revolución es invencible” in faded red letters across buildings; the dilapidated mansions and rickety bicycle taxis; the cigar shops clogged with snowbird tour groups; and the kids who follow you around, ask where you live and, when they find out it’s New York City, shout, “New York Yankeeeeees!” (I didn’t have the heart to tell them I grew up near Boston.)

At the same time, in a country where almost nothing has changed for generations, I found cranes erected across the city in preparation for renovations and construction. New paladares pop up almost weekly, as do small pizza shops. Hotels are filled with tourists; at Meliá Cohiba, where I stayed, I heard more American accents than I usually do walking down a random New York City street.

Now that the country is opening up for the first time in over five decades, hope, determination and money are in the air, and everything is up for grabs: real estate, construction, telecommunications, tourism. Small businesses, from bicycle and car repair to plumbing, restaurants and taxis, are all poised for growth. Netflix has announced it is coming, despite the fact that just 5 percentof Cubans have Internet access, according to a 2012 Freedom House report. (Twenty-three percent of Cubans can access the government-sanctioned “intranet.”) In February, Conan O’Brien became the first late-night host to tape a show in Cuba since 1962 (the episode aired March 4). Which colossal American brands are next? Home Depot? Best Buy? McDonald’s? Royal Caribbean International? Donald Trump?

Cuba is suddenly brimming with potential, restrained by a tentative government and populated by hopeful, hardworking people. Who, exactly, stands to benefit and who could be left behind? Is Cuba’s future a newfangled Jamaica, thronged by spring breakers, bachelors and bachelorettes wearing Che Guevara T-shirts and Castro-style Army caps? And is that a best- or worst-case scenario?

The Art of Change

“I remember having my mom pick me up at school and say, ‘We have 24 hours to leave. Pack a suitcase. We’re going to be traveling outside of Cuba,’” Magnan says. “It was scary.”

Forty-six years ago, Magnan’s mother, an art professor, and his father, an accountant for a tobacco factory, left everything they owned in Havana—car, furniture, jewelry, possessions. Even then, Magnan was a collector: baseball cards, stamps, coins, stickers. “I loved to draw but was never pushed into the art field. The Cuban mother wants you to be a doctor or lawyer.” Instead, he became an art dealer.

Magnan is known for showing Cuban artists like Roberto Diago, who explores race, religion and Afro-Cuban roots; Alexandre Arrechea, a founding member of the collective Los Carpinteros; and Glenda León, who represented Cuba in the 2013 Venice Biennale. His first time back to Havana, in 1997, was during Cuba’s Special Period, the economic crisis that began with the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Cuba lost billions of dollars in support and subsidies. There were shortages of everything: transportation, food, electricity, cars, replacement parts, toothpaste. Once-stunning homes started falling down, creating the kind of dilapidated beauty that fuels ruin porn. “I fell in love with the artists because what they were doing during the Special Period was very different. They had no materials. They were working with paints that were not paints. Canvases were metal or fabric or mops. They’d take everything they could and make it into art. I said, ‘Oh my God, the U.S. collectors have to see what’s going on here.’”

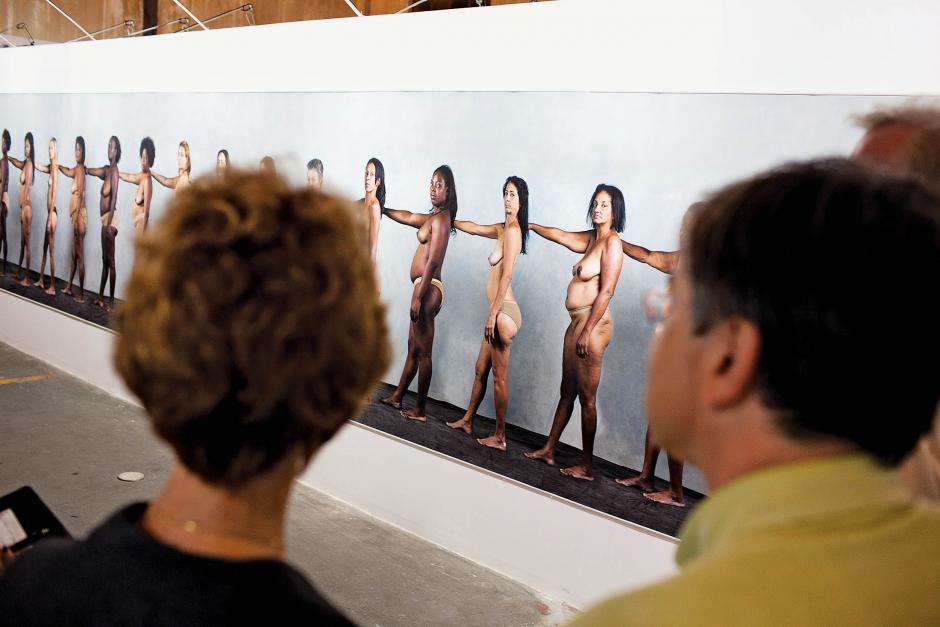

Today, Magnan is behind some of the most innovative and controversial art events in Cuba, including Chelsea Visits Havana at the National Museum of Fine Arts in 2009, the first art exhibit of American artists in Cuba since the revolution. The event was part of the 10th Havana Biennial, which, despite its name, has occurred every three years since 2000. “That was a key turning point in Cuba-U.S. relations, when I realized art can make a difference,” Magnan says.

Over the past few decades, a handful of Cubans and Cuban-Americans have been working quietly as cultural ambassadors, building bridges between the two countries by focusing on the arts. Magnan is one of them. “Havana is alive and well,” he says. “Artists are doing incredible things. And they are choosingto remain in Cuba to pursue their careers…. The changes that are happening through art and culture are making the way for other changes.”

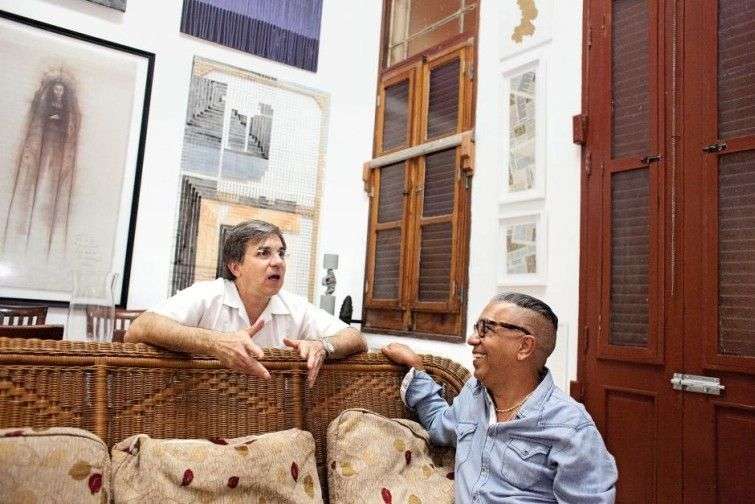

On our second day in Havana, we visit Cuban curator Juanito Delgado at his apartment overlooking the Malecón. It’s early evening as we gather in his living room, which is covered floor to ceiling with framed paintings and photographs. He leans back into a deep wicker couch, crosses one red velvet slipper over the other and says (through Magnan’s translation), “When you make good art, it poses all of the political questions. Don’t make politics art. Make art political. Then you have the dialogue.”

In 2012, Delgado transformed the Malecón into an art exhibit for the 11th Havana Biennial. Arlés del Río’s Fly Away featured the silhouette of an airplane cut into a large, rectangular chain-link fence placed at the edge of the seawall. Rachel Valdés Camejo installed a large mirror facing the water; she called it Happily Ever After No. 1.

“Art moves society, and art moves people,” Delgado says. “I hope Obama will help the cultural scene here, give funding to make books, do shows and help artists promote their work…. I want Havana to have its theaters filled.” He pauses for a moment, then looks straight at me. “Bueno,” he says. “Maybe you could find out where [the new money] is gonna go?”

One Less Brick in the Wall

Cuba is just 90 miles from the United States, but it has been essentially frozen in time since 1959, when Fidel Castro overthrew the dictator Fulgencio Batista with an army of guerrillas. Under Castro’s Communist reign, education and health care were free but the economy crumbled, poverty spread, and Cubans were rarely permitted to travel abroad. Castro has a long history of punishing and repressing critics; in 2013, there were over 6,000 arbitrary detentions of human rights activists, according to the Foundation for Human Rights in Cuba. Freedom of speech does not exist here, the state owns all official media outlets, and the government has intimidated bloggers and locked up journalists, who face gruesome conditions in prison.

Since 1982, Cuba has been on the U.S. government’s list of countries that sponsor terrorism because, according to a 2013 State Department report, it has offered “safe haven” to members of the Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA), in Spain, and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, and it also harbored fugitives wanted by the U.S. That designation prohibits Cubans from banking with America. While Barack Obama has promised to review Cuba’s status, Republicans are protesting the potential removal.

In 2008, Fidel’s brother Raúl took over. In the past few years, he has instituted a series of reforms that permit Cubans to travel abroad more easily and for longer periods of time; buy and sell cars and homes; legally start private businesses (with over 100 types); and stay at Havana’s international hotels. (Historically, Cubans were shut out of high-end hotels, partly because they accept only the tourist currency, CUC (pronounced kook), and state workers earn their wages in the essentially worthless Cuban peso (CUP), and partly because the government didn’t want the hotels to become hotbeds of drugs and prostitution.) While Raúl’s policies have been applauded, the economic reality for most Cubans has not, since the majority can’t afford to do any of these things.

“The reforms, even as reforms, are tepid, halting and partial,” says Fulton Armstrong, who served as national intelligence officer for Latin America from 2000 to 2004 and is currently a Senior Fellow at the Center for Latin American and Latino Studies at American University. “[When] you don’t have the influx of new capital, new trade, new money coming in, even if opportunities exist, the resources for using those opportunities do not exist.”

The average Cuban makes less than $20 a month. Last year, some doctors reportedly got a pay increase from $26 a month to $67. In an appliance store I wandered into, a microwave was on sale for $72.60, and a coffeemaker cost $30. Most meals I ate were around $30 a head. Now that Americans can send Cubans $8,000 a year, up from $2,000 before Obama’s December announcement, the gulf between blacks and whites is expected to widen. According to The New York Times, white Cubans are 2.5 times more likely than blacks to receive financial support from relatives abroad, making it easier for them to start businesses. White Cubans living in rural areas are also likely to struggle, Armstrong says.

There are 11 million people in Cuba, and many stand to benefit from the thawing of U.S.-Cuban relations: tradesmen, farmers, all those who receive remittances from relatives living abroad to enable them to open up small businesses. “The informal economy of Cuba is massive, and it’s been the training ground for large sectors of society to practice entrepreneurialism,” says Armstrong. “Some, like artists, have been doing it for decades, and they’re very good at it. People who’ve stayed on the straight and narrow, either because of personality or closeness to the party or institutional affiliation with tight oversight, haven’t engaged as much in the black market. Those people will have a slightly slower start.”

The losers, Armstrong says, are those who tend to lose everywhere, every time: the poorly educated, the elderly and those with health problems.

“Always, change is good for a group of people and bad for another,” says Meylin Bernal, 32, a tour guide with San Cristóbal, one of Cuba’s state-run tour companies. “Everyone is excited about having the chance to work and, according to their wages, be able to have a normal life. Not to struggle, but to survive.”

‘The Sun Is Different Here’

“That’s a Muscovy. Russian! That black one is a Chevy, 1953. I used to own some of them.”

Raphael has been shouting the names of cars we pass as we drive through Havana. “That one over there, the green one, is a Chevy, ’52. That one is a Mercury, 1951. That’s a Dutch ’58. That used to be a Shell gas station before the revolution.”

We’re heading to Párraga, a poor neighborhood on the outskirts. It’s about a 30-minute drive, so to pass the time, I ask him why he decided to stop working as a doctor. “The wage was not enough!” he says. Raphael says he earned between $12 and $15 a month. (Today, doctors earn four times that, he points out.) As a taxi driver, he earns about $200 a month, which helps him support his family. “At the beginning, I missed my work as a doctor, but now it’s so many years working as a taxi driver—”

He trails off.

“Juan Carlos just graduated dentist university in July,” Raphael says of his 24-year-old stepbrother. “He worked two days for me and made $30 a day—more than he makes in a month. It’s awful. Juan Carlos would like to go to the U.S. He’s studying English. I’ll send him some money to help him. There’s no future for him here.”

We pull over on a quiet street and pick up Sandra Soca Lozano, a 28-year-old Cuban psychology professor at Havana University who has agreed to spend the day with me. Lozano is short, with long brown hair, big brown eyes and a friendly smile. She lives with her mother, a psychologist, and father, who’s retired, and her grandfather. She’s never left the island. “Because I love my country and I love my parents and I’m an only child, I don’t want to leave them behind,” she says.

When Lozano is not teaching at the university, she volunteers with children and teenagers who have cancer. But like other Cubans who opt to keep their government jobs, she makes a measly income—just $30 a month. (“Every Cuban does the black market to make purchases and earn money,” says Armstrong, “because obviously the $30 income is not her only income. Don’t kid yourself.”)

Lozano longs to buy a car and go salsa dancing with her friends, but both are luxuries beyond her means. The challenges of daily life are compounded by watching her peers succeed abroad. “Lots of friends live outside of Cuba, and after four months they have cars! And they have houses! They can go on vacations wherever they want. My parents, who work like hell, cannot do regular stuff. My mother can’t go to Egypt and look at the pyramids.”

We continue driving, past abandoned gas stations, bus stops teeming with people and an old port without boats. I ask Lozano what it is about Cuba, aside from her family, that keeps her here. “It’s the people, the places,” she says. “Structurally, the streets suck and the buildings—I know that. But the smell from the sea! I’ve always lived near to the sea. This is a particular smell that I love. The sun here is different. You can always find someone who’ll help you, who’ll share with you.”

“Oldsmobile, 1955!” It’s Raphael again. He explains that we’re driving through a neighborhood called Luyano. We pass people sitting on stoops or standing on sidewalks waiting for a communal taxi. A large sign that says, “Gracias Fidel” hangs from a bridge.

Eventually, the streets get rockier. After a few more turns, we end up on a wide, pothole-ridden street devoid of cars and covered in trash. People are hanging out in the streets, and dogs roam the sidewalks as if they own them. Aluminum sheets serve as fences around tiny houses that are nestled up to each other like sardines. This is Párraga. There is no tourism here, and the water doesn’t run every day. A friend suggested we spend some time here, and introduced me to someone who might offer a window into what life is like on this side of the city.

Justina Cordero Mesa greets us on her porch, stretching her thin, wrinkled hands out toward mine and kissing me on the cheek. She’s wearing a white print dress, dark green socks and black flip-flops. Her white hair is clipped in a messy twist on top of her head, and fluffy white eyebrows hang over her eyelids. Her face is marked by deep creases. She’s 90.

Mesa waves us into her home and points to the couch and a couple of chairs covered in brightly colored pillows. Lozano, Magnan and I sit down. It’s a tiny space, not more than six by eight feet. Cracks and stains line the pale mustard walls and tiled floor. In one corner, a tiny Christmas tree and a boombox sit on a small brown table. On another table are a vase of fake flowers, a green piggy bank and a couple of other miniatures. Hanging above the table is a framed photo of Fidel Castro. Outside, dogs are barking.

In a raspy voice, Mesa tells us her television was recently stolen when someone broke in through the window. When I ask if the culprit was ever found, Mesa laughs.

Her home is small, dark and filled with flies. Behind the living room is a small dining room with a wooden table and short refrigerator covered in vegetable-shaped magnets. In the even-smaller kitchen, old buckets and some cups and bowls sit on a makeshift countertop. There is a plate of what looks like chicken bones near a hot plate, and four cooking utensils hang from the pale blue wall. The ceiling is low, not just here but in all of the rooms. A small door in the kitchen leads to a back alley, where Mesa hangs her clothes and washes her dishes.

“My grandson wants to take his house and this house and trade them for one bigger house, so that I can live with him. But I don’t know,” says Mesa, who has lived here for more than 60 years. Her husband, who worked for the police, died a few years ago. They have one son, who lives in Cuba, and her sister and niece live in the U.S. “My sister wanted to take me, but I didn’t want to leave. I have my family…. My history is big. But what am I going to do with that?”

I ask Mesa if she thinks life in Párraga will get better now that change is starting to come to Cuba. “It hasn’t changed. Every day it’s worse, because everything is more expensive,” she says. “I can’t hear or see well. I’m very old. I’m really old. Whatever I’m gonna see now I’ve already seen.”

When I return to New York City, I email Lozano. She says it was “hard” to see how Mesa lives. “On the other hand, she represents exactly what I think it is to be a Cuban, because even living in those conditions she would never leave her country. She loves it. She hopes for good things for others and not for herself. She offers the few things she has, and she is old but still…independent and she still cares of her family.… For me that’s the essence of the Cubans—always take care and worry for someone else, always resilient, always helping the other, even if you don’t know him too much.”

‘Will They Beat Up People?’

Vedado, an urban center in Havana where Hugo Cancio has been slowly growing his media empire, is a long way from Párraga. Cancio, who’s Cuban, is the founder and CEO of Fuego Enterprises, which focuses on business, media, telecommunications, real estate and travel opportunities in Cuba and the U.S. A few years ago, he and his wife were on a flight from Miami to Havana along with about 40 Americans. He overheard some of them talking about what Cuba is all about—“other than that famous last name that starts with a C,” he says.

“Is Cuba a militarized country?”

“Will we find people with machine guns in the street?”

“Will they beat up people who say bad things about Fidel?”

“My wife said, ‘Why don’t you get up and tell them what Cuba is all about?’” Cancio recalls. “I was getting pretty upset, because as you can see, this country is about more than Castro and the dissidents and the opposition. It’s a beautiful country with beautiful people. I approached them and started talking to them about Cuba.”

Twenty minutes later, he returned to his seat. His wife had an idea: print a brochure about Cuba, to be given to tourists on flights to Havana. “Do something!” he remembers her saying.

Instead of a brochure, Cancio launched On Cuba, the first Cuba-focused bilingual magazine, which is sold throughout the U.S. and Cuba. Its website gets between 600,000 and 1.2 million visitors a month, and the magazine and its sister publication, ART On Cuba, which Cancio launched last June, are sold in all U.S. Barnes & Noble stores and all Hudson News shops at Miami International Airport and Ronald Reagan National Airport in Washington, D.C. This month, the magazine goes into 184 Publix supermarkets across Florida. And in a nod to his wife’s original idea, On Cuba is the official in-flight magazine on most charter flights between Miami and Havana.

Cancio, 50, was born in Havana. His mother, Monica Leticia, was a famous Cuban singer, and his father, Miguel Cancio, co-founded the legendary Cuban quartet Los Zafiros (the Sapphires), affectionately referred to as the Beatles of 1960s Cuba. During the famed 1980 Mariel boatlift, when Castro announced that anyone wanting to immigrate to the U.S. could leave the country, 125,000 Cubans fled on 1,700 boats. Cancio, then 16, left with his mother and 13-year-old sister. Not long before, he’d been expelled from his prestigious high school for making a joke about Castro. “My mother said, ‘You have no future here,’” Cancio recalls. “‘We gotta go.’”

With no relatives in Miami and nowhere to go, they spent three weeks in a shelter at the Orange Bowl stadium. Later, they moved to a tiny studio in South Beach. “My mom slept on a sofa bed, and I slept on the floor on a mattress for three years. She regretted her decision for many years.”

Back in Cuba, Cancio’s father had been working with the Ministry of Culture’s Centro Contraciones, but he lost his position for permitting his family to leave. He got a job as a street sweeper and later worked in construction. “I’m the only construction worker who goes in a three-piece suit to work,” Cancio recalls his father writing in letters. A few years later, he, too, left the country.

Today, Cancio is a pioneering ambassador for Cuban music and art in the U.S., especially in his hometown of Miami. He has produced nearly 140 concerts and 30 music tours, and his résumé reads like a primer of the Cuban-American culture wars. In 1999, he planned a concert at the Miami Arena for Los Van Van, one of the most successful Cuban musical groups. “Right-wing Cubans were outside throwing eggs and cans, and their sons and daughters were inside dancing,” he recalls.

Cancio was also behind the first Cuban-American feature film produced in Cuba since before the revolution, Zafiros, Locura Azul (Blue Madness), about the rise of Los Zafiros. The film premiered in 1997 at the Havana Film Festival, where it won the people’s choice award and then ran in theaters for six months. When he brought it to Miami, thousands of protesters rallied outside the theater. “My mom had brought me to this country to be a free man and to have a better future,” he says. “How can you prevent me from doing something I have every right to do in a democratic country your parents brought you to because in Cuba you couldn’t do anything?”

With U.S.-Cuban relations changing, Cancio is expanding the On Cubafootprint. In March, On Cuba Real Estate will arrive, focusing on architecture and local neighborhoods. This spring he’s launching On Cuba Travel, a Travelocity-type website focused on Cuba, and, later, On Cuba Money Express, a money remittance business. He’s also partnering with two large telecommunications companies in the U.S. (Blackstone Online is one; he declines to name the other) in an effort to bring the Internet and cellphones to the Cuban people.

“I have been fighting for this for many, many years—not defending the government but defending my right as a Cuban to change U.S. policy towards Cuba, which was inhumane and didn’t work, as President Obama said,” Cancio says. “All of that combined has given me some credibility in Cuba.”

Who, exactly, stands to benefit from all of the work he’s doing? I tell him about Lozano, the psychology professor, and Mesa, and ask him what he thinks their futures will look like.

“I’m concerned the first people that will benefit will be the well connected,” he says. “It will be a lengthy process, but we are breathing a different air. I see it in my people who work for our publication. I’ve seen the transformation from when they started working with us to how they are today. They’re happier. Their houses are being rebuilt. They’re thinking of putting a little money aside to take a trip to Mexico or Honduras.”

The On Cuba office is empty when I visit on a Saturday, save for the editorial director, Tahimi Arboleya. She’s sitting at a desk in one of the offices, surrounded by a few computers. On her desktop: Gmail and Facebook. It’s the first time I’ve seen those websites during my entire trip. It’s also one of the few times I’ve seen working computers.

“I think that we can do something. A little, you know?” says Arboleya of her work at On Cuba. “It’s very, very important to us to inform Cubans and Americans [about] what happens in Cuba, what is the reality of the Cuban people. The information about Cuba in the United States is very—I don’t know how to say in English—polarizing?”

My last night in Havana, I invite Lozano to join Magnan, me and a few others for dinner. At first, she isn’t interested. She’s supposed to meet up with some friends to go salsa dancing, which she hasn’t done in weeks, but after making a quick stop at the salsa club and finding out it’s full, she decides to join us. Raphael drops us off near the water in the Miramar section of Havana. A bouncer stands at the foot of a walkway leading up to an imposing white house. He and Magnan talk—it looks as if they know each other—and then we head into Rio Mar, a seafood paladar overlooking the Almendares River.

We sit at a long table on the terrace, beneath a navy blue awning. All around us are tables of tourists: Americans, French, people speaking Spanish and more Americans. White Christmas lights hang from the balcony, lighting up the clear glasses and bottles of Acqua Panna. Lozano keeps commenting on how clean the water tastes. She’d never had blue cheese before, so she orders chicken breast in blue cheese sauce. Before dessert arrives, she disappears inside and takes photos in the restaurant’s lobby, posing on a couch with one of the waiters.

“That place, it’s kind of magic. I felt like I was move to another country or time,” she says later in an email written in nearly perfect English. “[It] makes me nostalgic of my future, of my parents, of my family to be, of my country…. But I know that in the current situation of my country’s economy, and the struggles of my government to keep public systems like health and education with quality, working in my field (education) will never allow me to go by myself to places like that. I will always have to wait to be invited by someone else.”

In Cuba, she says, “there are lights and shadows everywhere and you can choose what to show, but most important for me how to show them both.”