In less than three months, Alberto could be flying over the Atlantic. He is not a plane, a balloon, a missile, a kite, a zeppelin. It is the name of the first tropical storm that will occur in the Atlantic cyclone season that begins on June 1 and is anticipated to be cruel and excessive due to the presence of La Niña.

At this short distance from meteorological dangers, a Rice University professor reminds us of our fragility in the face of a nature that, cyclically, becomes brutal.

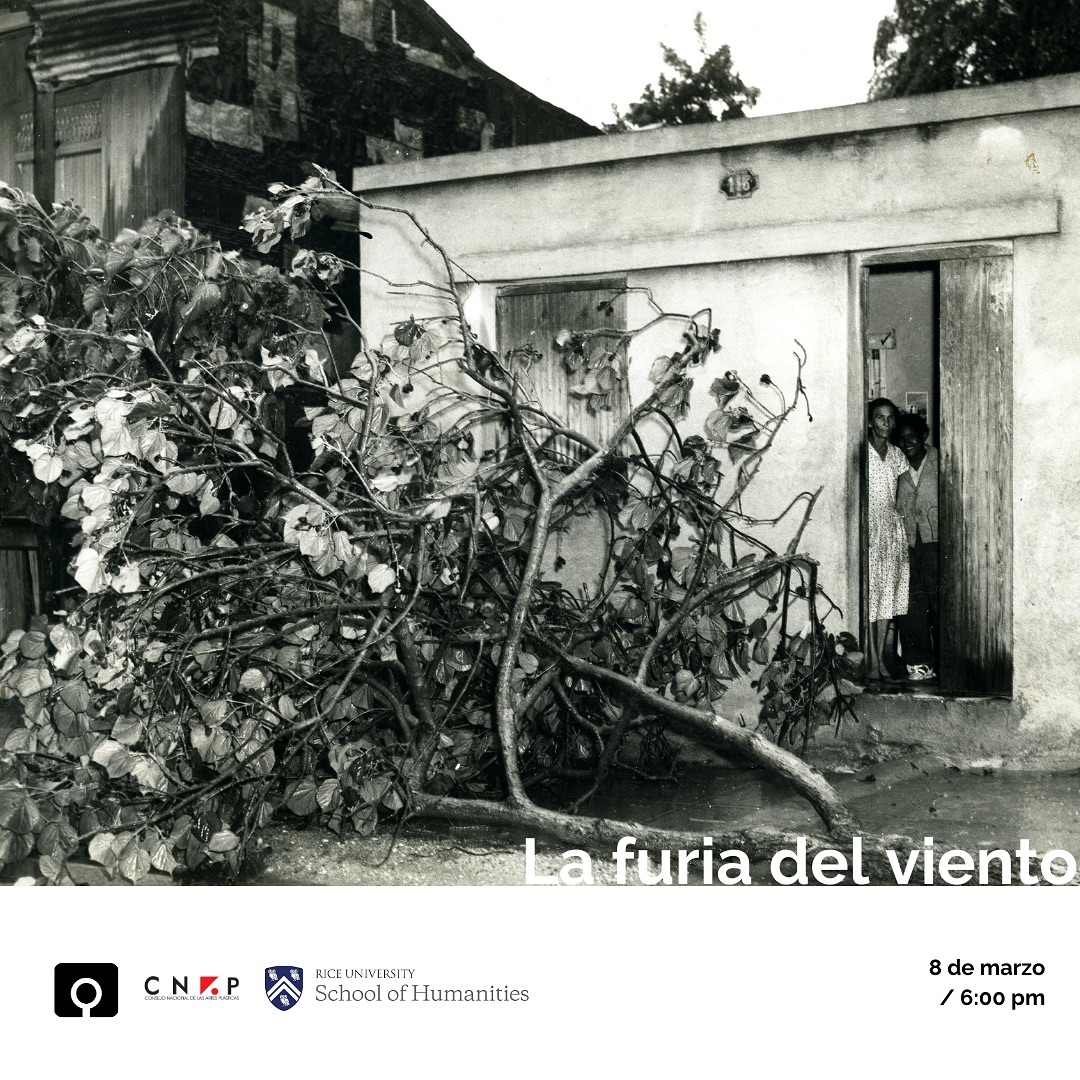

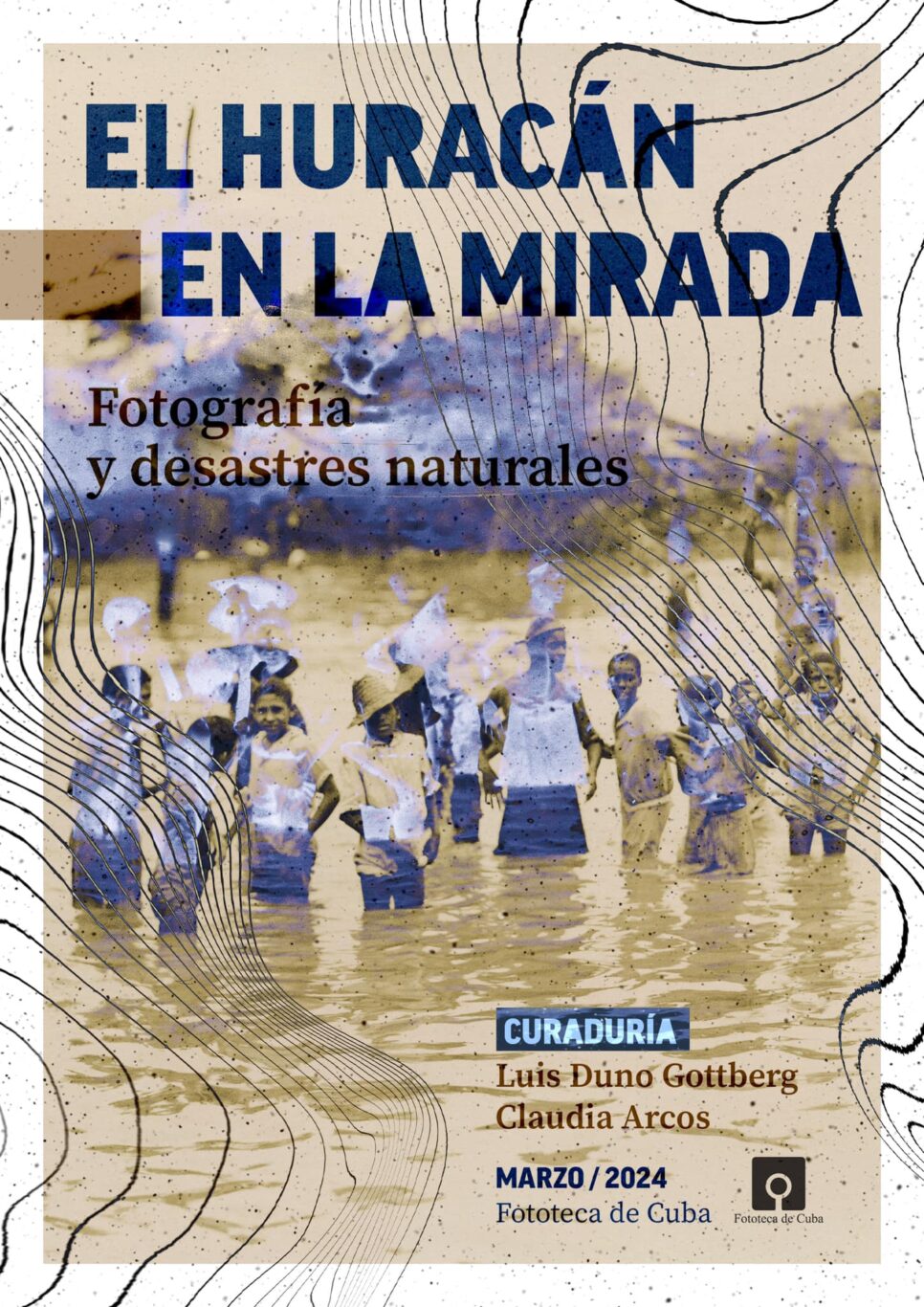

More than a year ago, professor Luis Duno-Gottberg (Caracas, 1968) had a series of informal conversations with Cuban curator Claudia Arcos. Those talks eventually became the exhibition La furia del viento, which was inaugurated on Friday, March 8, at the Photo Library of Cuba.

Electronically, Duno-Gottberg was eager to respond to OnCuba’s questions.

The investigation examines the personal motivations and academic perspectives that this passionate researcher of Latin American realities had to delve into the excesses caused by what many call, with a certain fearful — but deserved —reverence, Mother Nature.

La furia del viento is made up of Cuban photographers and filmmakers Moisés Hernández, Ernesto Ocaña, Santiago Álvarez, Samuel Feijóo, Marta María Pérez Bravo, Raúl Cañibano, Armando Capó, Alfredo Sarabia Fajardo and Manuel Almenares.

What is the zero point of this sample?

A little over a year ago I had been carrying out extensive work to build a “critical archive” of photography of natural disasters in Latin America and the Caribbean. This is an ongoing work, but the Cuban case crystallized in an extraordinary way in an exhibition, a catalog and a book.

What was your original idea?

My original idea was not only to systematize the existing archives, but also to develop a typology and even a taxonomy to understand natural disaster photography.

And what about the reaction of Claudia Arcos, the curator?

Claudia Arcos responded enthusiastically and professionally to that invitation and, thanks to her vast knowledge of Cuban archives and photography, we were able to gather materials spanning more than 120 years of history.

However, it is not an exhaustive or totalizing sample, but rather a “cut” in time that seeks to reveal blind spots in history and surprise the audience.

We think that La furia del viento is a very important contribution as the first effort to visualize the archive of natural disasters in Cuba.

Our greatest wish is that from now on, more conversations will develop and new archives, suggestions, ideas will appear…. In fact, we invite those interested in the topic to write to us with questions, ideas, clues.

Finally, it must be said that a fundamental driving force of the project lies in Claudia Arcos’ passion for the photographic archives of the Cuban nation.

What is your opinion of Cuban photography regarding natural disasters and how technologies have modified the visual perspectives of the authors?

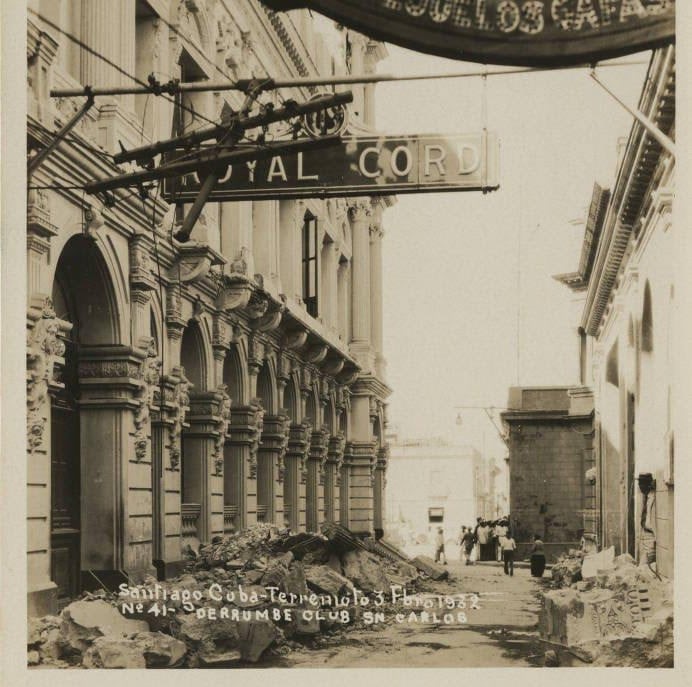

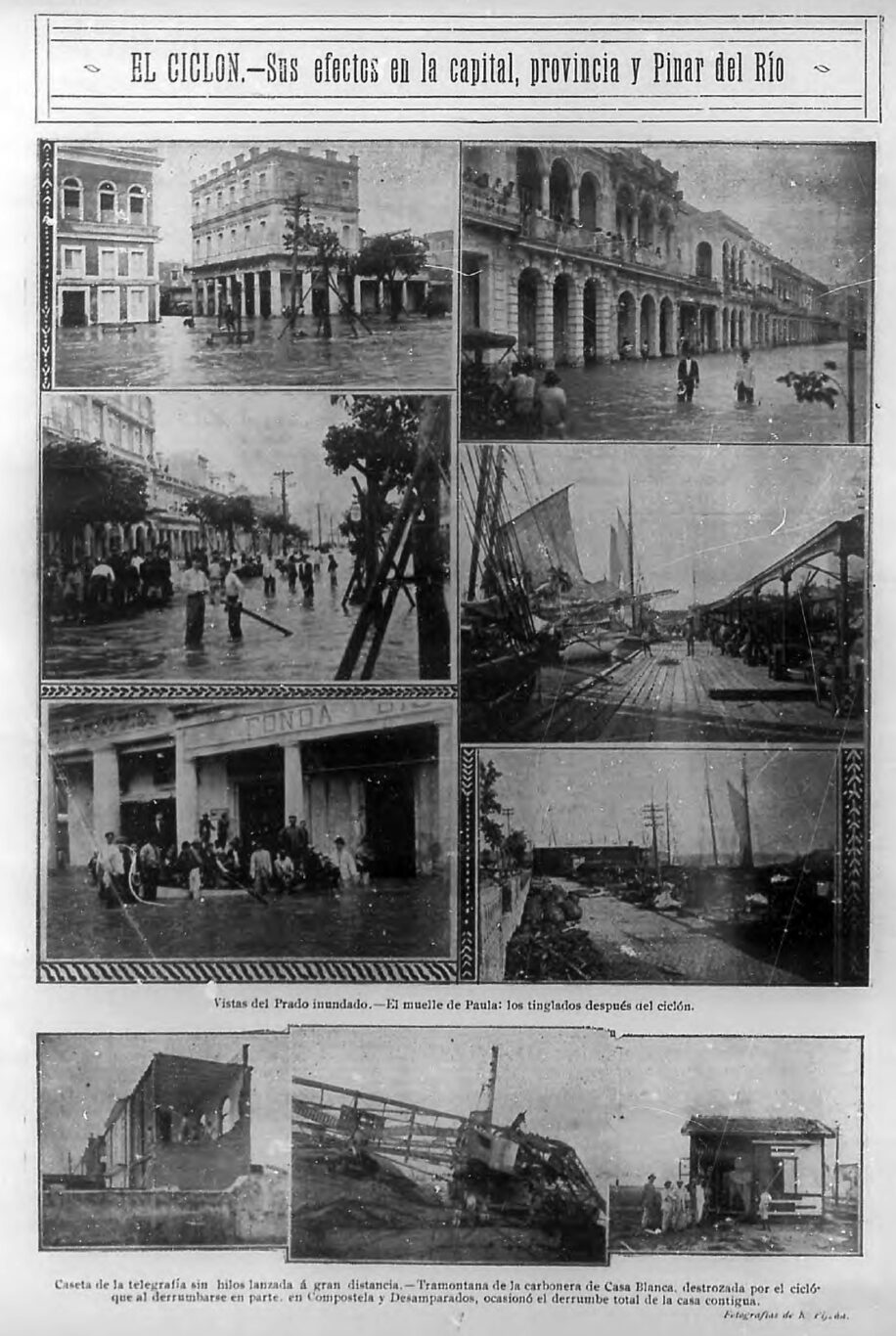

Cuban photography has meticulously captured the destruction caused by natural phenomena. In the archives that we have consulted there are examples dating from the beginning of the 20th century. Much of this photography could be classified as photoreportage. Other examples constitute technical inventories of the disaster, documenting both landscape alterations (urban or natural), and structural failures in buildings and means of communication.

However, there is another body of work that explicitly transcends the documentary. They are works of art focused on “the sublime” or the mysteriousness of the natural disaster.

In a book that is almost ready that I will publish with Iberoamericana Vervuert (Madrid), I propose that the different examples of photography of catastrophic natural events constitute what I call a “visuality of disaster.”

What is the concept about?

The concept is important because it requires seeing these images within a precise system of representations, historically shaped and susceptible to methodical analysis. In these photos we can identify recurring characteristics and functions that represent a “genre” or “sub-genre” within the photography of events-landscapes-disasters.

Diario de Cuba appears in the funds worked on. Could you refer to that source, so that it is not confused with a current digital medium of the same name?

Thank you for this precision, because, in effect, we are referring to the Diario de Cuba from the beginning of the 20th century, in Santiago de Cuba.

There we have discovered expressions of the work of little-known photographers, but fundamental to Cuban history.

Curriculum vitae. Synthesis

Luis Duno-Gottberg specializes in Latin American and Caribbean culture from the 19th century to the present, with an emphasis on “race” and ethnicity, politics and violence.

His current book project, Gente peligrosa: hegemonía, representación y cultura en la Venezuela contemporánea, explores the relationship between popular mobilization, radical politics, and political representation in that country.

His previous and ongoing work on “prison communities” investigates the daily life of these prison environments; from Venezuela and Brazil to the Dominican Republic, as a specific biopolitical order that affects civil society in general in Latin America.

Additionally, Duno-Gottberg works on cinema in Venezuela and on the Haitian Revolution, and translated the first Haitian novel, Stella, from French first to English (2014) and then to Spanish (2016).

Written by the political exile Émeric Bergeaud (1818-1858), Stella recounts the independence of Haiti through a fictional and symbolic construction of the events, as well as an elaborate criticism of the society that emerged after the independence process.

Currently at Rice University in Houston, Texas, Duno-Gottberg is an academic professor at the Baker Institute for Public Policy and serves as an associate professor at Baker College.

What curatorial criteria was followed by you and Claudia Arcos?

Thanks to Claudia Arcos’ exhaustive knowledge we have been able to combine materials from the archives with more recent materials.

The curatorial criterion is based on the taxonomy that I propose in the book that I mentioned and a series of additional considerations proposed by Claudia (transcending the photoreportage, the spiritual dimension of the phenomenon, direct access to unknown documents, etc.). There is a dialogue here between the interests of the curators; but I think the brilliant touch comes from the Cuban curator who has introduced glimpses that — only? — the national public will know how to interpret.

Finally, my interest in Cuban audiovisuals led me to propose elements that Claudia arranged in a separate room and that I believe will surprise the audience.

You warn that the exhibition is part of a larger, regional scope, on the visual capture of natural disasters. What areas of contact and lack of contact would Cuban photography have with respect to its Latin American and Caribbean peers?

As I said, this exhibition is part of a broader project with Latin American scope. In fact, it is also part of a course on this topic that I have been teaching for years at Rice University in Houston.

Regarding the specifically Cuban qualities of this photograph, two things catch my attention. Firstly, I feel that there is a certain modesty or even an acute ethical conscience regarding the representation of death. In other Latin American archives I have seen an overabundance of images of disaster victims; but in the Cuban case there seems to be a smaller number of these photos. I don’t want to advance a hypothesis in this regard, but it is something that must be explored.

Another issue that I find fascinating and that I have not seen to the same extent in other archives is the religious theme. I believe that the image of the disaster and the experience of Cuban religiosity are linked. From the iconography of Our Lady of Charity of El Cobre to the references of Afro-Cuban religions to “the tail of the cyclone,” there is a very powerful spirituality that Cuban visual culture has been able to address. It is an element that Claudia was particularly emphatic about, and successful in unveiling.

I think that in the near future it would be important and even beautiful to be able to take this effort to Santiago de Cuba and, later, to other places where the cyclones have struck…. I am extremely grateful for OnCuba’s willingness to disseminate this exhibition, focused on such an urgent issue for the Caribbean people and, in particular, the Cuban people.

Catalog notes written by LD-G

The native peoples of the Caribbean knew of the wrath of the gods; because they had already experienced the manifestations of angry cemíes, such as Guabancex, Goddess of the Winds, who ruled “juracanes” or swirling winds that destroyed everything in her path, expressing her fury against those who offended her.

Before barometer and seismograph records existed, there were signs in the sky and in the sea, premonitory of the destructive forces that affected crops and the general well-being of populations. Guataubá announced the imminent arrival of a storm with clouds, thunder and lightning. Coatrisquie governed the uncontrollable waters that flooded valleys and fields, bringing death and disease.

It wasn’t all destruction. There was also the balance between Boinayel (rain) and Marohu (drought); and this meant a truce for the people, thanks to the playful relationship and reciprocity inherent to the deities; when not the result of offerings from chiefs and shamans who sought to appease their anger with rich offerings.

Beyond the immediate and concrete event, the experience of what secularization reduced over time to “natural phenomena” depended and still depends today on a universe of visual representations: images that allow us to conjure the fury of the gods; remember the dimensions of the event; honor the memory of the victims; or know and scientifically study the phenomena. All of this depends on images that, as a whole, constitute what I define as the visuality of the disaster: a codification of signs, aesthetics, views and, in general, cultural imaginaries that give meaning (and therefore existence) to phenomena that, from our human fragility, we call “natural disasters.” The visuality of the disaster is thus a system of representations anchored in a particular story that, however, when it becomes something akin to “common sense”; to something that “is what it is,” is something unequivocal. An earthquake looks like any earthquake. A hurricane looks like every hurricane; and so on, disasters occur within a seemingly finite repertoire of representations.

Here it is worth asking uncomfortably about the fatigue that discursive genres produce; due to the wear and tear of the images; because disaster photography has the characteristics of a genre that borders on landscape photography, war photography and even the red note; because the repetition of images could produce desensitization and indifference. That is to say, isn’t there a moment in which the disaster becomes a contumacious repetition of themes and images? Are there so many ways to show the collapse of a structure after an earthquake? How many different frames can we make of a city submerged under the waters of a stormy sea? Isn’t every land devastated by a cyclone, the same landscape of rubble flattened by the force of the winds?

This is a paradox: the recurring nature of the representation coexists with the incommensurability of the event itself.

I believe, however, that the repetitive naturalization of representations is not so much the result of the finitude of the phenomenon or cognitive fatigue, but rather a consequence of an impossibility of language in the face of the unsayable.