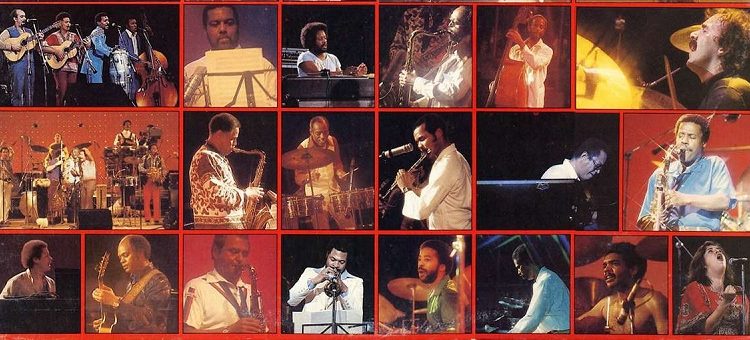

In 1979, cultural relations between Cuba and the United States after 1959 witnessed a historic event. For the first time in that time frame, musicians from both countries came together on a stage in Cuba to play and collaborate for three nights. Billy Joel, Weather Report, Stephen Stills, Rita Coolidge, Pablo Milanés, Irakere and the Aragón Orchestra were some of the American and Cuban groups and artists who, at least on the stage of the Karl Marx Theater, allowed politics to give way to diplomacy of music and the communicating vessels between the cultures of both peoples.

However, few Cubans know about this event of invaluable importance, due to the meager promotion it was given in the country’s media, both in print and on television.

Cuban filmmaker and cultural promoter Ernesto Juan Castellanos has dedicated the last 11 years of his life to the making of a documentary that highlights the meaning of this event and somehow rescues it from the mantle of oblivion that has covered those warm nights flooded with rock, jazz, trova and traditional Cuban music. Three days of historic concerts that, however, the vast majority of the followers in Cuba of that music could not enjoy because the entrance to the theater was, sadly, by invitation. Hence, many Cubans who vibrated (and vibrate) for jazz, rock or blues could not be part of that historical moment.

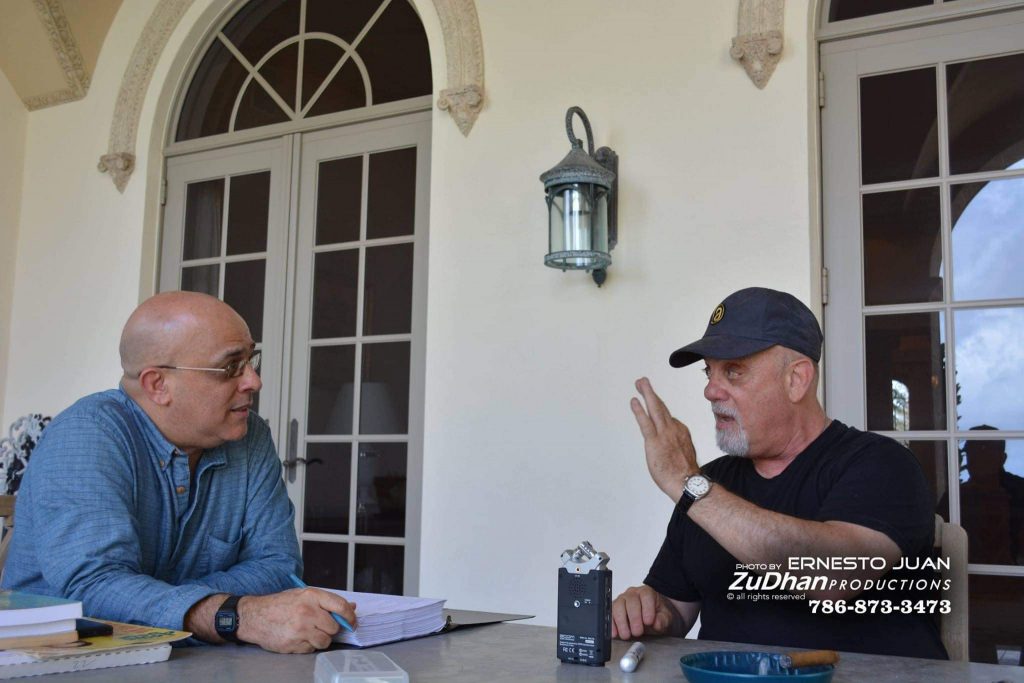

I spoke years ago with Ernesto Juan, who currently resides in the U.S., when the creative process of the documentary was halfway through. I resume that talk now that Ernesto is about to turn the work into reality, after 11 arduous years of research, in which the protagonists of Havana Jam 79 fully entrusted their memories to him.

Can you tell us about the research process for the documentary?

It’s a project that I began to carry out in 2009, when the 30 years of Havana Jam were commemorated. A very dear friend, Dr. William De Jongh, very enthusiastic about this celebration, asked me to write an article to publish in Juventud Rebelde. He had already published several things in the newspaper such as interviews with Silvio, among other works. So I decided to find someone who could tell me about the event, as I did not participate. In my search I found Chucho Valdés, who had played with Irakere at the Havana Jam and raised the name of Cuba. For the Americans, the name of the meeting was Havana Jam, and for the Cubans, Cuba-USA.

Chucho Valdés gave me such a good interview that I decided to look for video cameras, lights and microphones to continue the investigation. In more or less a month I managed to interview all the Cuban musicians who participated in the event, many people who were in the audience and all the organizers. That was enough to prepare a video that was going to be like a small trailer, as a summary of the documentary. Initially, I only had it in mind with the Cuban side, since I lived in Cuba. In 2011 I came to live in the United States. At that stage the process continued. Now I’m basically talking to musicians from the Fania All-Stars orchestra. Many of its members have died and those who remain were then very young. They have given me very valuable testimonies, as is the case of Rubén Blades. It has been an 11-year investigation that is not over yet.

Why do you think it’s important to make this documentary?

For the value of the event, not because it’s my documentary. Havana Jam was the first time that Cuba and the United States shook hands on stage, in an organized way. I say in an organized way because two years before, in 1977, a group of jazz musicians came to Cuba and had an unofficial meeting with Irakere at the Habana Libre Hotel. Then they were invited by Irakere to play with them at the Mella Theater.

Even in 1975 an American cellist, Christine Walevska, visited Cuba, invited by Fidel Castro. She made a short tour of art schools and houses of culture. In 1979, already in an organized way, the Havana Jam was held. It was a small window that was opened, under the administration of then President Jimmy Carter, for a rapprochement with Cuba.

Other types of approaches had been made, in the fight against terrorism, hijacking of planes and work in fishing areas. The Cuban Interests Section had been opened in Washington and the United States Interests Section in Havana, and the possibility had been provided for Cubans living in the United States to travel to Cuba.

Musician Stan Getz spoke in New York to Bruce Lundvall—who was president of Columbia Records—about the strength of the musical movement in Cuba, and that it was worth it to come to the island, to meet musicians and sign them to his label.

There was the possibility of holding an event that was brief at first, but later it became a very big one. The best of the Columbia Records label converged on this stage, such as Billy Joel, Kris Kristofferson and the Fania All-Stars. Cuba brought a representation of some of its best styles.

Havana Jam allowed the United States and Cuba to put politics aside, so that culture would predominate, because both countries had very close roots and this was confirmed there. Hence the importance of the event. The first and second nights ended with jam sessions, in which musicians from Fania, the group from Matanzas Yaguarimú and Pacho Alonso participated. The second day musicians from CBS Records played with Irakere. The third ended with Billy Joel. Unfortunately, there was no jam session there because the Cuban rockers did not share the stage with Billy Joel. It was a very big cultural and political event. Shortly after the Havana Jam, the doors were closed again, after Republican Ronald Reagan became president of the United States. He closed all kinds of communication with Cuba.

Why do you think the Havana Jam is hardly known in Cuba?

I’m still surprised that Cuba agreed to hold this event. We were at the end of the so-called gray five-year period, in which the slogan of ideological divisionism was still a lethal weapon against anyone who had cultural inclinations other than the rumba, guaguancó, rum and tobacco. Anyone who loved jazz, blues, rock and roll or pop was branded as ideologically divergent.

It was a term that was unfortunately coined in the cultural and political life of Cuba. Many people who had long hair or followed fashion similar to that used in the United States were frowned upon. At that time, the United States brought its best jazz musicians, a style that was seen in Cuba as an imperialist expression. Rock music, of course, was viewed with suspicion by Cuban cultural and political censors. On the other hand, the so-called salsa music of the Fania was interpreted as misappropriation of Cuba’s cultural values. These three styles that converged by Columbia Records were prohibited or, if not prohibited, at least vetoed or frowned upon in the Cuban press.

People hardly knew about Havana Jam because it was not given the promotion it deserved. Very short notes were published in Juventud Rebelde, Trabajadores and Granma, in which it was said that a musical event was going to be held between Cuba and the United States and that tickets were by invitation.

The invitations were given to reliable people, members of the Communist Party, outstanding workers. It’s true that invitations were distributed to outstanding students of art schools, but very few.

The general public did not have access to the tickets. I imagine that the country’s policy was not to promote something that was neither popular nor massive. Had it been given the promotion it deserved, the Karl Marx would have been packed for the three days of the event. It was not given because Cuba considered it was not important.

Afterward, the coverage was minimal. A short note came out in Juventud Rebelde. El Caimán Barbudo published an article that said that Cuban music had triumphed, because it was very difficult to replace Tata Güines’ hands with the synthesizers that the Americans brought, as if to say that the United States had only brought a lot of technology.

The idea was to compare the event to a match, a boxing match in which Cuba had won. That was the concept that was used on the island. That is why people don’t know about it. They don’t know that Billy Joel, the Fania All-Stars and the most important artists of Columbia Records were in Cuba. The curious thing is that in the United States it was not given much coverage either. Forty-one years after Havana Jam, it seems as if nothing had happened.

How was the process of contacting the protagonists?

It has been an 11-year process, which continues. In Cuba I dedicated myself to looking for the musicians who participated, many of whom have already died. Generally, when I interviewed a musician, he gave me the contact of another and a kind of network was created. Thus many doors were opened to me in Cuba and in the United States.

When I arrived in the United States, I decided to start promoting the event. I opened a page on Facebook and a channel on YouTube and published the trailer that I made in Cuba in 2009, saying that I was a Cuban filmmaker who was trying to locate American musicians who had participated in Havana Jam. On Friday of that same week I received a private call (the number was not identified on my cell phone) and it was Billy Joel. I thought it was a friend who was playing a joke on me, but it was, indeed, Billy Joel.

Billy Joel’s was the first interview, because he called me. He opened the doors to other musicians because they thought that if an artist like him had given me an interview, my work was serious. In 2015 I did a great many interviews. I’ve already covered most of the participating groups. Now I’m in the process of interviewing musicians from Fania, a large group, whose members were already well grown at that time. The first Fania musician I spoke to was Rubén Blades, who gave me a fabulous interview.

Now I’m going to organize the production to interview the rest. It’s a documentary that needs funds, money, that uses very expensive equipment and I need to travel a lot to make it. Also, I have to take into account copyright issues regarding music and videos. It’s an expensive process. I’m looking for funding again to finish what’s left and a company that wants to premiere it on Netflix or at film festivals.

Did any event at Havana Jam surprise you?

When I started making the documentary, I knew almost nothing about Havana Jam. I wasn’t a fan of Fania, or Billy Joel or Rita Coolidge, or the Cuban musicians who were there. I started this project as a researcher and journalist, not as a fan.

I hope that at some point the documentary will have historical significance, because it reflects an event that almost nothing was said about. CBS gave me access to all their files and I was amazed at how it was done.

I learned how the event was handled, the conditions set by Cuba and that CBS gladly accepted. The United States did not set conditions. I recently spoke with Fania tres musician Nelson González, and he told me about the exchange they had with Pello el Afrokán in a collateral activity at the Pinomar Club. He defends that Cuban cultural values were violated in many ways by Fania.

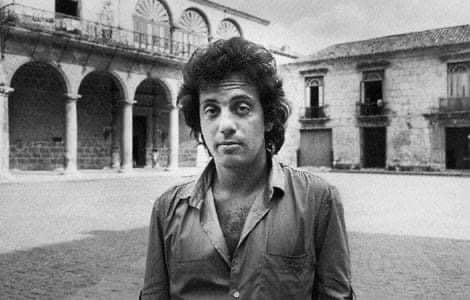

It’s nice to hear Billy Joel saying that he saw musicians on stage in Cuba that he never thought he’d see in his life. Billy Joel’s drummer told me that his concert in Havana was the pinnacle of his career. Many of these musicians never thought they could visit Cuba. They spent three fabulous days and they have told me things that have brought me to tears, because of the love they feel for Cuba and its music.

Several years ago, cultural authorities confirmed to me that they planned to reissue this event, 40 years after its celebration. Were you aware of those preparations?

I was even in the process of the holding of those concerts. I met with officials from the Ministry of Culture. Cuba was willing to hold this festival, with concerts for three days. Musicians who participated in Havana Jam 79, along with other young artists, were going to be brought in. Workshops were scheduled in music schools, the Higher Institute of Art and the National School of Art.

Unfortunately, the event’s organizer, Bruce Lumball, then president of Columbia Records, was old and sick and eventually died. The production companies that were going to put the money withdrew, because they no longer had any commitment to Bruce. The event never happened.

Others have been held, such as the Music Bridges, in 1999, a meeting in which American musicians and the British Peter Frampton held workshops at the Hotel Nacional de Cuba, where two Cuban and American musicians were randomly chosen to work as a team and individually, to compose songs. This event had characteristics similar to Havana Jam, in the sense that no tickets were sold and access was by invitation. It was another attempt to make exchanges between American and Cuban musicians.

I didn’t like it because the public was left wanting to hear the work of the great musicians who participated, not the songs composed for the occasion.

Do you have a release date for the documentary?

The idea was to have the documentary ready for the commemoration of the 40 years of Havana Jam, in 2019. For that, I met with Sony and proposed they make a package, in which the original discs of the concert and the DVD of the documentary would come out. Sony was interested, but then suddenly withdrew.

I don’t have a release date yet. Actually, I’m now unemployed due to lack of funds, waiting for an executive producer to give the missing money. The work is almost finished.

What significance have the artists you interviewed given to Havana Jam?

They have all been interested in having the documentary ready and they have called me to ask me about the premiere. I’ve had a lot of spiritual support, but little financial support.

The interviewees have shown a lot of interest. Most of them have assured me that going to Havana was one of the best things that has happened to them in their careers. Artists like Billy Joel, Rita Coolidge and many more have told me so. It has been very important to listen to them.