The mansion is an imitation of the African hunting bungalows. It is at the entrance to the city of Caibarién and at present is a center for the care of the mentally ill. But beyond its peculiar construction, this was the childhood home of Robert McNamara, who was U.S. Secretary of Defense during the Vietnam War and later president of the World Bank.

The U.S. politician spent his early years among the coconut and mango trees in the mansion’s garden. That’s how the oldest neighbors of the zone remember it.

José Antonio Patiño is a fan of the history of Caibarién, which was established near the city of Remedios. For him “the McNamaras’ stay in the city has been one of those unresolved enigmas of the so-called Villa Blanca, since they hardly mixed with the community. They lived their lives there, as if they were in the United States.”

According to Benito Carreras, the Caibarién Historian, the father of the family, Eduard McNamara, was the representative of the only U.S. company that had business in the docks at that time, a commercial entity that basically was in charge of linking the Villa Clara locality with New York through steam ships. Carreras says that around 1930 several dock workers plotted against the life of Eduard in revenge for the salary cuts, but he was able to come out unharmed.

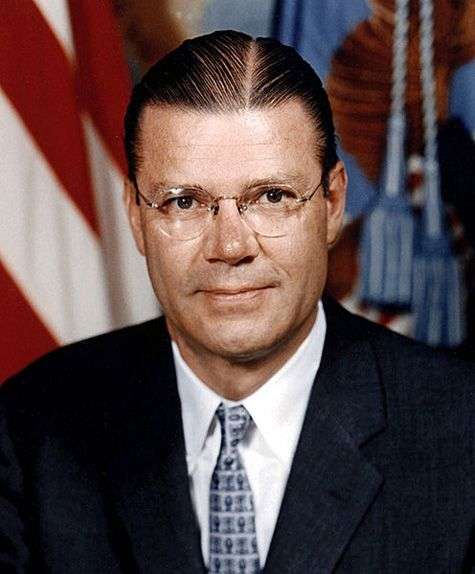

McNamara

“One of the plots had to do with the house’s lock with soap and taking advantage of the delay in opening it to shoot Eduard McNamara, but it was leaked out. The plan included the flight to the town of Isabela de Sagua of five workers who were involved, an event that occurred before the fall of dictator Gerardo Machado.”

The personal secretary of McNamara father was shot and died later due to a post-operation infection. José Antonio Patiño says that the doctor who dealt with the case, the subsequent mayor of the city Pepito Cabrera, almost immediately married the secretary’s widow. It was a time in which all the streets of Caibarién were not paved and crab runs were becoming cyclical and impressive. In fact, one of the family father’s pastimes was to watch how hundreds of thousands of these crustaceans invaded his home’s alleyway.

“That man was captivated with the crabs, he used to say that it was worthwhile living here just to see that spectacle,” I was told by Carmen Rodríguez, whose family had a house close to the McNamara’s mansion. “They were not proud people, they were communicative. The boy was very active and that led to his being scolded constantly,” she adds.

The father of that family used to take walks through the city, always accompanied by an enormous black German shepherd dog. It should be taken into account that in Caibarién there were antecedents of confrontations between the townspeople and the gringos since there was a U.S. military base during the occupation period. A certain feeling of enmity was logical, Carreras comments. Moreover, the McNamaras had done like Hemingway: they built a piece of the United States in Cuba and they hoisted the U.S. flag because, in the words of Eduard himself, that was U.S. territory, a property that covered many hectares around and that included what today is the Vietnam Heroico Zoo.

After Machado’s fall, the McNamaras returned to the United States, which leads Carreras to suppose Eduard had some sort of connection with the dictatorship.

After the triumph of the Revolution in 1959 the McNamaras’ Caibarién mansion, already in the hands of a local family, passed on to state goods and a district with housing units started being built right beside the mansion of the U.S. family.

There’s another story behind this event, apparently insignificant, and it is the one that joins two opposite figures of world history. On May 9, 1964, Vietnamese guerrilla fighter Nguyễn Văn Trỗi was taken prisoner when he was about to blow up a bridge through which the already by then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was going to pass. The death by firing squad of the rebel leader in October 1964 became a legend for the international left, and in Caibarién the neighbors and the authorities decided to give the name of Văn Trỗi to the district that included the former mansion of the U.S. family.

Poetic justice or historical vengeance? The truth of the matter is that those events are still remembered today by those who built the new community, through the Cuban system of family mini-brigades.

Life around the mansion is monotonous. The coconut trees still grow in the garden that surrounds it and the wooden pendant that distinguishes it from the other family buildings of the city is still solid.

The house is cool and private; anyone can feel it is a mansion to be lived in with love. Popular legends tell of the appearance of lights in the garden and of supposed burials proper of the African religions. Other mythical visions report about some nighttime ghost in the rooms that divide the bungalow.

The McNamara family that is still living today perhaps remembers its faraway presence, or perhaps has forgotten it with the passage of time. The date in which it was built is engraved on the iron entrance fence: 1926. That was a flourishing era for Caibarién, when persons from all over the world established their residence in the town.

The years and the circumstances gave the mansion and the city another course. However, there still reigns the stealth and tension in the building’s every nook and cranny. Everyone who arrives there cannot stop themselves from asking about the origin of such a singular architectural style in the middle of a town in the interior of Cuba.

The place has become the locality’s patrimony. Sometime ago an enormous pit overflowed in the garden of the mansion and the people’s demand to protect the beauty of the site was enormous. Even in the local media there was news of the rescue of the McNamara house. Today, by the coconut trees, one can see a garden full of sunflowers. There isn’t a trace of that overflowing pit.

Popular oral history points out, as an unconfirmed comment, that Robert McNamara was born in Caibarién, but all the official biographies place the event on June 9, 1916 in San Francisco. There is no proof in the local parish church or probative document contradicting his birth in the United States.

Perhaps because of the years he lived in Cuba, as president of the World Bank he held the belief that the problems of the developing countries could be resolved with a strict plan. Diametrically opposed to the Caribbean nation starting 1959, that false Cuban would never again see his family’s mansion.

Benito Carreras tells that in 2002 Robert returned to the island to participate in an event about the Missile Crisis, but he didn’t visit Caibarién. At the time many approached him as the historian of the locality to find out about McNamara’s past in the Villa Blanca. Today the mansion survives, old and singular, as proof of an episode not frequently narrated in the history of relations between Cuba and the United States.

My ancestor, Mitzi Reuter, was the governess for the McNamara children from 1930 through 1932. Eduard’s full name was Andrew Edward McNamara. His children were Andrew Edward McNamara III and Caralyn McNamara. According to my information, Robert S. McNamara was not Eduard’s son.

My information comes from a file on Mitzi Reuter held in the US National Archives . The file was created during WWII. Mitzi was arrested and interned for 2 years during the war along with many other German and Italian aliens living in Cuba.