The exhibition En busca del origen opened this Saturday, January 27 at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Castilla y León (MUSAC), bringing back the work of Cuban artist Ana Mendieta (1948-1985), one of the pioneers of contemporary art that prefigured currents that were later vibrant in the 21st century.

The exhibition is a novelty in Spain, since in more than a quarter of a century the European country had not dedicated a personal exhibition of Mendieta’s plastic production.

The curators brought together more than a hundred works that cover seventeen years of production by the artist (1968-1985) who, together with her sister Raquel, left the island under the umbrella of Operation Peter Pan.

Organized by the United States government and the Catholic Church, the program, in force between 1960 and 1962, took more than 14,000 minors out of Cuba heading north without family or guardian accompaniment in one of the most traumatic and controversial immigration events in bilateral history.

Many were never reunited with their families.

The exhibition includes photographs, videos, sculptures, installations, drawings and paintings, including iconic works such as silhouettes or cave graphics, as well as a set of thirteen unpublished pieces.

It also includes her drawings on amate paper, a selection of paintings executed between 1969 and 1971, the recreation of an installation made in 1978 and a set of photographs discovered in September 2022.

The person responsible for her legacy, her niece and goddaughter Raquel Cecilia, highlighted that the exhibition explores how Ana Mendieta “never stopped reinventing herself, developing a new sculptural language, often ephemeral, sometimes performative, always fueled by her research into the original myths and cave painting.”

“Far from being understood as a retrospective, the project focuses on revealing Ana Mendieta’s relationship with the visible and the invisible, the permanent and the ephemeral, her way of making the unspeakable explained through the trace of the body and its insertion into nature,” she added.

The body as laboratory and standard

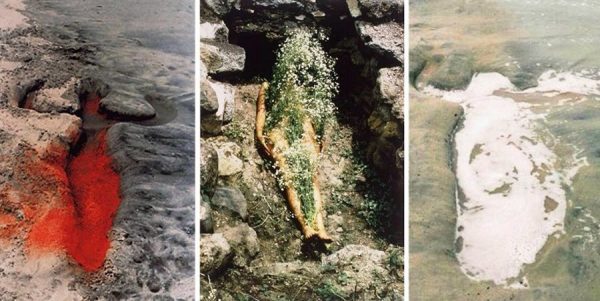

Throughout the 1970s and first half of the 1980s, Mendieta created a powerful body of work defined by the body and its encounter with nature.

In just over fifteen years she developed her own hybrid practice, which fused aspects of body art and land art.

Ana Mendieta: “Si no hubiera sido artista, hubiera sido delincuente”

Her exceptional series Silueta (1973/1981), comprising hundreds of works created in the state of Iowa, in the Mexican desert and other locations throughout North America and, finally, in Cuba, form the central corpus of her art.

For thirteen years, until her untimely death at the age of 36, Mendieta generally carried out her actions privately in front of a camera.

She documented her actions in short 3-minute films (shot on a Super 8) and on 35mm slides, from which she selected and printed photographic copies.

For Mendieta these documents provided alternative ways of witnessing her art.

A pioneer

For many, the pioneer of the fusion between body art and land art, for others a pioneer of ecofeminism, Mendieta reformulated the artist’s relationships with nature through performance, a term that she always shied away from given her hatred of certain repeated formulas.

To define her telluric work, she used the term earth body.

With that profile she undertook her approach to the practice of art in which she took herself as an object, incorporating her own figure — or her silhouette or her footprint — into the natural landscape.

Escaleras de Jaruco

One of her scenarios had that experience in the Escaleras de Jaruco park, in the current province of Mayabeque, in whose caves and places intervened by the artist in the early 1980s, of which some traces and sculptures barely survive time and vandals.

Her rabid contemporaneity is defended by her ecofeminism, the denunciation of gender-based violence — of which she was presumably one of the fatal victims — the veneration of nature, the revaluation of ancestral wisdom, the use of one’s own body as an interpretive resource and the longing search for the keys to identity.

“The heartbreaking force of her appreciations of violence…or the use of unconventional resources for that time such as her own body, photography and video, make her art a vital, committed, visceral tool,” estimates the professor. Cuban Kirenia Rodríguez, author of the work Ana Mendieta: isla y geografía interior

Violence of the final point

Ana Mendieta died at dawn on September 8, 1985, at the age of 36.

Naked and with signs of abuse, she fell from the 34th floor of a New York skyscraper that she shared with one of the leaders of the minimalist movement, her husband, the American sculptor Carl André.

Her death cut short a growing international notoriety as she was appreciated as an avant-garde in the exclusive circuits of the United States. Her work had reached the showcases of institutions such as the Guggenheim and the Metropolitan in New York.

Carl André died a couple of days ago. He was 89 years old. A jury found him innocent, but the suspicion of murder followed him for the rest of his days. It was a living shadow that he couldn’t kill.