During the first decade of the 20th century, waves of U.S. immigrants arrived in Cuba to found farms where they produced citrus, fruits and vegetables. In all the provinces they created communities: Omaja, Bartle, Herradura, San Cristóbal, Ceballos, Isla de Pinos, just to mention some of the best-known. Almost nothing has been said about others. Such is the case of the Chicago community, in Itabo, Matanzas.

This town belongs to the municipality of Martí. Its name is an indigenous word that means “land surrounded by water.” At the end of the 19th century, it was the second most important town in the Guamutas judicial district.

Its socio-economic progress was influenced by the connection to the railway from Júcaro to Cárdenas, where the port guaranteed trade and the transfer of passengers.

As a consequence of the war, its population decreased and its agricultural infrastructure was devastated. Four years after the end of the conflict, in 1902, it barely had 252 inhabitants.

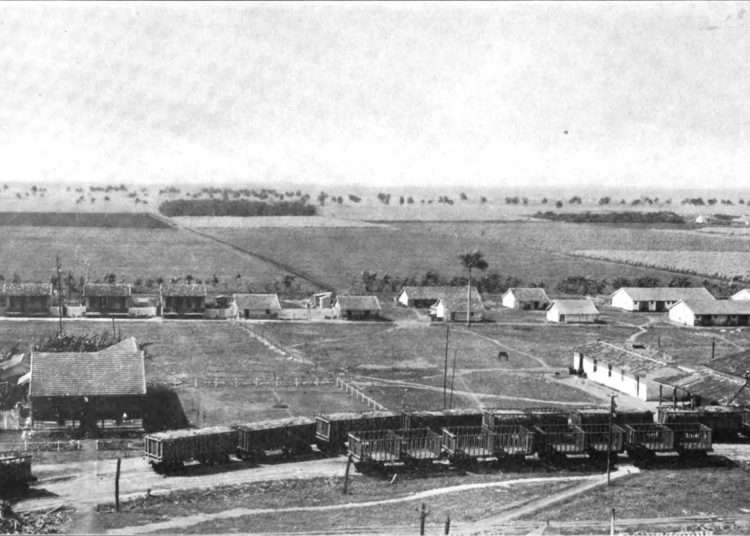

The establishment in the old San Juan site of about twenty families from the United States would help to change the situation. In the month of February 1907, a reporter from The Cuba Review and Bulletin came to that place to investigate how they were doing. He did not sign his chronicle, published in the April issue. It is a short text, but it provides interesting details about daily life and the names of those who left behind the paralyzing cold, in search of a better climate and more beneficial job options.

Wilderness tamers

The journalist looks with astonishment at the crops of vegetables, bananas, strawberries, pineapples and oranges, planted by the settlers on small farms of 20 to 40 acres, some larger. The crops are transported in carts, pulled by mules. The landscape is adorned by palm trees.

According to another reporter at the time, the company that sold the plots of land, based in Prado, Havana, and represented by R.H. Leeder, did not play fair:

“The land they cultivate is of poor quality. Suffice it to know that in those places only the sad cana palm trees show their ‘fans.’ It seems that the settlers acquired farms without knowing the lands they purchased. Despite all this, the settlers are satisfied and have good harvests of oranges, strawberries and other products that they export to the United States and we don’t know if to other places. A lot of tomato is harvested, which is turned into sauce and exported.”1

The harvest is not looking good, because the drought has been relentless in the first months of 1907. Luckily the farmers face the whims of nature through artisanal wells.

The largest farm belongs to J. A. Gutzen. He started planting strawberries in 1905; he proudly shows travelers the 1,000 robust plants of the New Oregon variety. The flavor of the fruits is exquisite; he started the harvest at Christmas and he plans to go on until the end of April. For a quart he’s paid 50 cents. He regrets not having had the same luck with the potatoes that grew little and thus it is impossible to export them.

- Rounds, in addition to being a citrus farmer, established a mixed shop. D. Rounds has shared the work on the land for two years with the raising of fowl. He sells chickens, for a peso each, to the inhabitants of Itabo and Cárdenas.

- Peck has specialized in growing pineapples on his 90-acre farm. For the time being, he sells his produce in Cárdenas, although, like almost everyone else, he dreams of exporting them to New York at higher prices.

A report dated April 4 in that U.S. city said: “Cuban potatoes have been more abundant this month, and they are generally quoted at very good prices. Red Bliss traded at $6 to $7 a barrel for nos. 1, and the crates of the same quality from $2 to $2.25, while the pink ones sold at a rate of $5 to $6 a barrel, and from $1.75 to $2 a crate, and nos. 2 from $4 to $4.50 a barrel. The aspect of the market is very favorable for good quality Cuban potatoes, which usually sell for a little less than those from Bermuda and a little more than those from Florida.

“The arrivals of pineapples from Cuba have been regular, and not having arrived any of this fruit from other sources, prices have remained firm and high, ranging from $2.50 to $4 per crate, depending on the size of the fruit, since the sizes 24 and 30 usually sell for $3.50 to $4, and those under $2.50 to $3.25, seldom less for extremely small and inferior fruit. Arrivals to date have been of very good quality, and there being no other stock, buyers do not pay attention to small defects.”2

Chas. H. Jones, waiting for the weather to improve, plants tomatoes and beans. The price of the former is 5 cents per lb. When travelers arrive at the home of Henry Taipales, their attention is drawn to how green are the rows planted with potatoes and tomatoes. The secret is that the owner maintained the irrigation for as long as necessary, transferring the water from the well. He complains about the high taxes that affect trade with the United States and the journalist takes notes, in silence.

Deer abound in the region. The farmers, armed with shotguns and accompanied by their dogs trained in hunting, go after the coveted prey on Sundays. Sometimes, the trusting animals come to the farms in search of food.

John H. Green makes charcoal, raises chickens, and also has beehives that earn him extra income by selling honey and wax. Those who have recently arrived are attracted to sugar production and will benefit most in the long run. The Tinguaro sugar mill, located in Perico, bought by the American Robert Bradley Hawley in 1899, will acquire all the ‘sugar cane it is capable of grinding. They will soon see how their neighbor Jack Caldwell, owner of the San Ricardo farm, dedicated to the cultivation of sugar cane and manager of the factory, will increase his wealth.

Jack was born in England and was a lieutenant colonel in the Liberation Army during the last independence war and was elected mayor in 1900.

Due to the proximity of the port of Cárdenas, these settlers feel motivated, despite the rigors of the climate and how difficult it is always to start from scratch. As of August 1907, they will be able to receive and send money orders at the Itabo Post Office.3

The fact that their countrymen settled in Herradura, Pinar del Río are already marketing vegetables in the United States shows them that their intentions are not a chimera.

- H. Leeder confessed to the chronicler of The Cuba Review and Bulletin that unfortunately the settlers have little capital, for this reason, progress is slower.

To educate their children, they built a school, where the U.S. teacher Ella Tallmadge, hired by the Company, taught classes from September to July.

The journalist returns to the city. The noise of the children still resounds in his ears. Then he will continue to pay attention to the news from Itabo, where Rodríguez, a correspondent for the Diario de la Marina wrote optimistically in November: “Despite the lack of rainfall, the fields in this region have a better presence in both sugar cane and fruits and the pastures are in excellent condition as can be seen from the good condition of the animals.”4

The last news

Among the U.S. settlers who established themselves in San Juan was Albert Hepper, who in 1912 denounced the presence of a group of rebels on his property, during the armed uprising of the Partido de los Independientes de Color. William Roud also had his farm in Itabo, in the 1910s. According to a journalistic note, he was a blind man who was helped by a daughter when he needed to travel to the United States.

Over time the ‘sugar cane plantations were consolidated. It was advantageous to invest in this sector because as a consequence of World War I, sugar reached high prices in international markets. tobacco and henequen were also grown in Itabo, but we do not know if some Americans dedicated themselves to these crops.

- E. Peck, who was vice president of the National Horticultural Society of Cuba, in 1918 decided to sell his seven and a half caballerias farm. His productive model illustrates how they adapted to changing times. A part of the property was dedicated to sugar cane. It also had 100 coconut trees, a thousand orange trees, and pastures for raising cattle.5 In that same year, the Cuban and U.S. company offered a 135-caballeria farm in Itabo, “the best land for cane and magnificent watering…”6

We have found the last references in a work by the Italian-Mexican traveler and historian Adolfo Dollero, published in 1919: “According to official data, the U.S. community in the province of Matanzas is represented by about 50 individuals. However, from my reports, their number turns out to be somewhat higher.”7

Dollero says that the inhabitants of San Juan were Finns. Perhaps, the same thing happened in other U.S. communities, where some Europeans arrived as a second place of emigration, among those pioneers: “Near Itabo there is also a community of Finns who today are mostly Cuban citizens.”8

More than a century has passed. I read in the press that in Itabo there is a farm called Chicago, perhaps it is the last vestige of that past, when U.S. families transformed, with effort and iron will, lonely places, turning them into productive regions, from where they exported crops and contributed to the Matanzas market.

________________________________________

Notes:

1 Diario de la Marina, December 7, 1907, p. 7.

2 The Cuba Review and Bulletin, April 1907, p. 25.

3 Diario de la Marina, August 9, 1907, p. 4.

4 Diario de la Marina, November 12, 1907, p. 3.

5 Diario de la Marina, July 26, 1918, p. 14.

6 Diario de la Marina, November 19, 1918, p. 14.

7 Adolfo Dollero: Cultura cubana. La provincia de Matanzas y su evolución, Seoane y Fernández Press, Havana, 1919, p. 404.

8 Adolfo Dollero, Op. cit., p. 383.