“If you see my love that I left again

I left without understanding what’s going on

In your heart hiding my country

And the garden that leads me home”

“De vuelta a casa”, Carlos Varela.

Sixela Ametller had not planned her pregnancy when, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, a Clearblue test warned her that Eva, her daughter, was on the way. Nor had she planned, four years earlier, to leave Cuba to try her luck in the United States; she never considered it until the opportunity arose, because that would only be a temporary journey, a trip with a round trip date, a dozen pieces of clothing, a few shoes, her cell phone with the Cubacel SIM card, and the bunch of keys to the gate, the door and her room in her parents’ house in El Vedado, Havana. But six years have passed since that day; and with Eva, her little one, it already makes two. Her first contact with motherhood was far from her home in Cuba and, as if that were not enough, the pandemic also robbed her of the possibility of living the pregnancy next to her mother, her best friend and her sister Lisset, her small tribe, its essential beings, although it also enriched her in many ways, that’s what she tells me. In the midst of all this roller coaster of emotions, between the joy of creating a life and the uncertainties of a world taken over by the fear of a microorganism, Sixela created “Empoderadas,” a podcast that, as she describes it, “intends to tell stories in Spanish of women entrepreneurs, who work in companies and at the same time have responsibilities at home: they are mothers, wives, daughters, etc.” Nothing, however, is so casual and isolated; they were not, for Sixela, neither the podcast, nor Eva, nor the decision to put on the shoes of a migrant woman.

“I see myself as a migrant woman. I remember that before becoming an immigrant, I listened to the song “De vuelta a casa” by Carlos Varela, and I didn’t understand it, but definitely that feeling of not belonging to any place is something that goes in an immigrant’s suitcase. Perhaps due to the circumstances that I have had to live through, I feel that I do not belong to this place [the United States], however, when I go to Cuba, I do not feel at home either. When I’m here I’m missing somethings, but when I visit Cuba, I feel that what I miss is no longer there, it no longer exists. I’m also Cuban, a wife, a sister, a friend and a mother, which is an important part of my identity now, I have many passions, communication is one of them, that is why, although I had not been exercising it for years, I decided to make it on my own and thus, the “Empoderadas” podcast was born. It is a project that fills me a lot and the most beautiful thing about it is the community of women that I’m building. At the moment I’m doing my master’s degree in Psychology as well and that is one of the passions that I recently discovered. Although I’m a communicator, I didn’t want to continue down that path and it took me a while to discover what I wanted to do and that is how I found Psychology. In addition, I feel that precisely because I’m a migrant, I can make a greater contribution to the Latino community in the United States, because here where I live, in California, it is not easy to find therapists who speak Spanish and the waiting list to access a Spanish-speaking specialist here is usually six months minimum.”

In 2016, when the opportunity arose to travel to the United States to participate in a congress of the Latin American Studies Association (LASA), she had not considered emigrating permanently, and I feel she does not say this out of habit, or to support a nostalgic or “politically correct” discourse; I feel that she was as surprised as many others to discover, at some point in the journey, that she had crossed the threshold where what had previously been uncertainty became a concrete life project outside of Cuba.

“My migratory story is a bit atypical because in Cuba I was living a moment in which I felt complete in the professional sense, I was doing what I liked and that was the ‘golden’ moment with the United States; it was the Obama era and I had the opportunity, through my work, to experience that moment up close. So, the idea of emigrating was not in my mind, I did believe that at some point I would leave Cuba to do some kind of academic mobility or professional improvement in Europe, where I had been before. It was what she wanted. Because of my job, I went abroad several times to work and I had already gotten an idea of what the world was like outside until in May 2016 I applied to the LASA event that would be in New York and they gave me a six-month visa.”

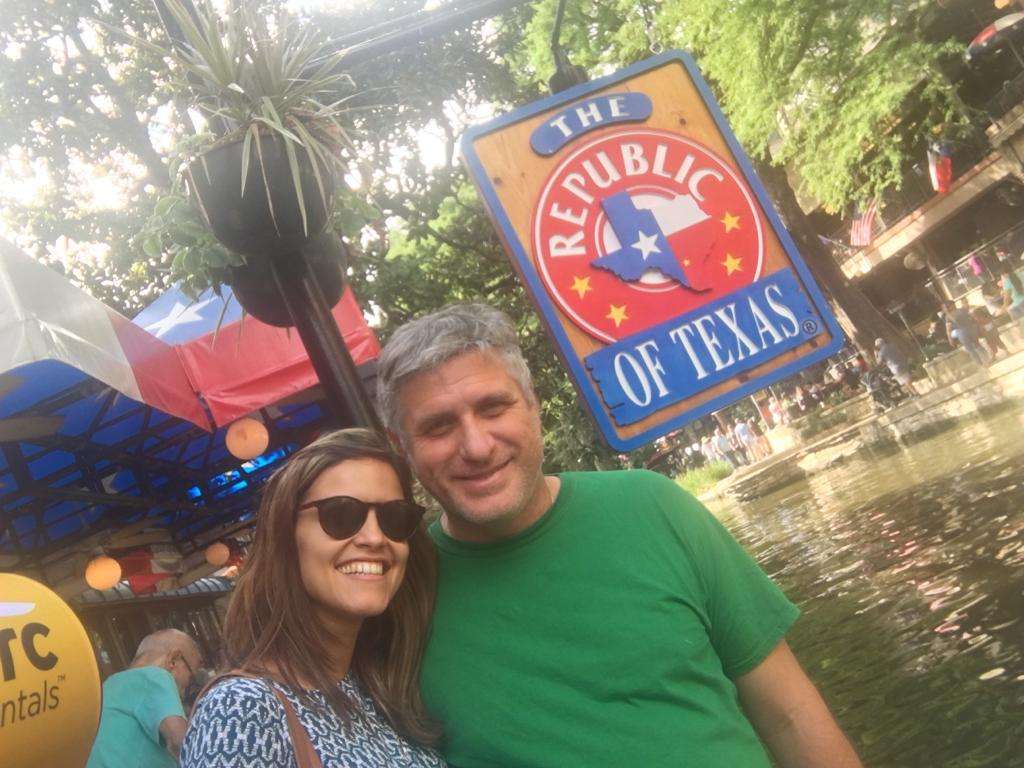

“I remember that I left Cuba saying that I was coming back, always with the idea of taking advantage of the visa because it was a single-entry visa and at that time my partner lived in the United States, so it would be an opportunity for us to live together for a while. However, while traveling with my partner in Texas and with little time left before my return to Cuba, he suggested that I stay. That was a very difficult decision for me, I didn’t sleep for a whole week because I felt deep down that I was betraying my family, my boss, but it also made me think about what I really wanted for myself and how I could actually return, if it would be feasible and realistic to return while in Cuba because it could be that they would deny me a visa, so thinking about that and especially what my growth prospects would be in Cuba after I returned, I decided to stay. On the other hand, my partner already had stability and that was important to make my decision, also where we were, in Texas, the atmosphere was very familiar, Spanish was spoken a lot and in that sense the transition was less shocking.”

“The idea of how to stay also kept me awake at that time, because as a Cuban I could perfectly have crossed to the other side of the border and benefit from the Cuban Adjustment Act, but that would mean that I would be two years without returning to Cuba, and I didn’t want that. So, the fastest option and the best in every sense was marrying my partner, who was a U.S. citizen and although we intended to leave that moment for later, we had to rush it to be able to be together. I recently spent a month in Cuba, it was the first time I had spent so much time there since I left, and there I discovered that there are definitely things in the context that I no longer want to deal with and where I no longer see myself in my day-to-day life. Even when I was visiting, when I did the things that I always liked to do when I lived there, I found myself feeling that something was missing, first because the people I knew were no longer there, the references and the dynamics of the people have changed, then you feel out of place. I remember that I met with a group of friends from the Lenin school, a friend added me to their group on WhatsApp and we planned a party. There I felt like a complete outsider, I no longer shared the same codes, so I got the feeling that what I miss about Cuba no longer exists. In fact, if one day I were to consider going back to Cuba to live there, I would have to carefully consider everything that would be missing.”

What do you feel changed you the most with migration?

First, the way I communicate, my life is in English now, at home I speak in Spanish, but outside it I do everything in English and that was a very profound change and at the same time a challenge, because I didn’t arrive in the United States mastering the language from here like many people. I remember that, when I arrived, on one occasion I was with some of my husband’s colleagues and I realized that I didn’t understand anything they were talking about, then I realized that I would have to challenge myself to master the language if I wanted to prosper here.

Now I’m doing my master’s degree in Psychology in English and that is possible thanks to my initial effort and investment in adapting. And well, in addition to the language, I have changed a lot, especially my way of thinking. In Cuba we have many conceptions that teach us to put the needs of the other above our own, that money is bad, and as an emigrant, a woman and a person who lives in a country where the culture is quite individualistic, I have had to transform those conceptions, resignify them to be able to adapt and defend myself. That is something that I have been trying to incorporate into myself, learning to prioritize myself, to take care of myself in addition to taking care of the other, and to earn money too, to internalize that there is nothing wrong with prospering financially or wanting to earn more than what you are offered or being better off financially. That prompted me to do a master’s degree so that, in the future, I could have my own business as a therapist here. My master’s degree has also been transformative, because it has forced me to review myself, to think about who I am, what I want for myself and for my future. Obviously, then, the Sixela who arrived in Texas six years ago, the Sixela from Minnesota and the Sixela who set foot on California soil three years ago have nothing to do with the Sixela of today.

What does it mean to you to be a woman, Cuban and migrant in California? How do these identity places condition and influence your daily life?

California is a multicultural place and, luckily, in the environment in which I move the most, which is academia, I have a strong bond and a lot of contact with a diverse group of people where, in addition, women predominate. That’s why right now I don’t feel any different; but in Minnesota, where I lived for a year, most of the population was white and local, and I remember that when I was in college there all my colleagues were white with blue eyes; I felt completely like a fish out of water. I also felt discrimination because of my accent, on several occasions in places where I have been working as a salesperson, clients told me that they wanted to interact with a person “who spoke English,” and that shocked me a lot because I was making an effort.

In addition to that identity issue, there is the pay and the gender gap when it comes to receiving a salary. Here, for every dollar that a man earns, a woman in the same position earns eighty cents, so there is a significant gap in that sense, which personally I have not felt much because as I have changed jobs quite frequently, I have never felt I was not being paid well or felt that I’m not able to grow professionally because I’m a woman, or that I’m stuck in a specific position.

How was your insertion in the labor market after emigrating?

When I went through the entire process to become a resident, I had to wait six months to get a work permit. When I achieved it, I ate up the story of the American dream because in the interview for my first job, which was in the sales area, the recruiter told me that there I would have the opportunity to grow according to my performance and that even in the future I could form my own team, but in reality it didn’t turn out that way and then I discovered that they paid me extremely poorly, but at that time I didn’t have any references. I worked a lot, I lost a lot of weight, and I was frustrated, that’s why after six months of being there I asked to leave. I left without having a plan B also because I had the support of my husband, even financially, and shortly after and with the connections I had made with the Jewish community in Texas, I was offered a position at the Honduran consulate. It was a very nice and enriching experience for me because I had never done this type of work and, furthermore, I saw a lot of purpose in what I did, which was basically to help and guide newly arrived migrants ― most of them undocumented, and they didn’t even know how to read or write to sign their names — about how they could insert themselves socially. I only left that position when I moved to Minnesota.

Still, looking for a job, making a resume and dealing with all that bureaucracy is a process that I’m still learning and that is very revealing for me, even in the area of self-knowledge, because I realize my behavior patterns, my tendencies to remain comfortable, even though I know that elsewhere I can find a better place for myself and even better paid.

On the other hand, there’s the master’s degree, which was something I always sought, because I knew that having a postgraduate degree from an U.S. university on my side would only bring me good results. I began to look for options and it first entered my mind to do something in the area of business administration because it was something that always caught my attention, so I began to attend many events of some courses to see how things were. However, I was not completely convinced, and I always postponed the entrance exam, I always made excuses not to do it until suddenly, during motherhood, which they say is a process that brings you a lot of clarity and also a lot of creativity, I decided to review a psychology program at Santa Clara University in California, which was one of the few that didn’t require you to do a PhD. I liked it a lot because, in addition, it would allow me to practice as a psychologist and open my own clinic. So, I applied and fortunately they accepted me. I received a loan from the government that at the end of the course I have to repay with some interest, because, although being Latina I could apply for specific scholarship financing for immigrants, to do so I had to be a citizen and, when I did the selection process, I still didn’t have the citizenship here. Anyway, I see it as an investment in me because if it wasn’t, I wouldn’t have been able to enter. I started part time when the baby was six months old and because of the pandemic everything was online, so at that time many of the classes were while breastfeeding Eva.

In the midst of all that process of transition, of changes, of reorienting the roadmap, motherhood arrives. Tell me, how was that process for you as a migrant?

Although I always wanted to be a mother, my pregnancy with Eva was not planned. It was a surprise to me. I took the test only because I have always been very regular in my menstruation cycle and when I saw that I was late, the doubt arose. When I saw that thing said “pregnant,” I went into shock. It was not a romantic comedy scene at all because it was not in the plans, we had the idea of going to live in Spain for a while and suddenly Eva told us that she was on her way and that it would be at that time and not another. I remember that I sat on the bed with my husband and told him, we talked about it, my husband gave me his support in any decision I made and after much thought I decided yes because, as we say in Cuba: “children always come with a piece of bread under the arm,” and if you wait for the ideal moment you will be left waiting many times, because the conditions are never perfect, although, of course, there are some contexts that are more favorable than others.

I had the baby in the middle of the pandemic, which made many things difficult, including being with my family or having people close to me accompanying me throughout the process. Also, my husband was in Europe at the time, and I was terrified, seeing the number of deaths from the virus and thinking that at that time I was responsible for another life, not just mine.

One good thing was that in the end everything was resolved and my husband and I were able to live together throughout the nine months, because we were both at home, isolated by quarantine; At that time I was collecting my unemployment and we shared many magical moments, like the baby’s first kick. Pregnancy was a very beautiful process for me despite all the fears and uncertainties; I loved taking pictures of my belly and talking and reading to Eva when she was still in my belly.

Coincidentally, my sister also had her pregnancy at the same time as me, the babies were born only 25 days apart, so we always exchanged a lot about how each one was experiencing this process, it was very special and essential for me, because since all borders were closed at that time. I couldn’t even ask for a visa for my mom to come to be here and accompany me.

Also, I was the first of my friends to be a mother, so I didn’t have many people close to me to talk and exchange ideas, sensations, fears…and that, along with the COVID-19 quarantine, was also a form of isolation that I lived gestating Eva.

On the other hand, the master’s degree in Psychology has helped me to be kinder with myself and not demand so much of myself as a mother; I have learned to be a “good enough” mom, as they say. They say that children have separation anxiety and that is something that I think is happening to me, it has been a challenge to go back to work, study face-to-face full time and pursue my professional goals without feeling guilty for not being with Eva.

There are better days than others, but when I leave the house at 8 in the morning and I know that I will only return at night, the guilt for leaving her is enormous, despite the fact that in the pandemic I had the privilege that not many mothers have to be with my daughter during her first two years. Now I explain to her that mom is going to work, but she’s going to come back, although it’s her mom who finds it hard to understand. And that makes me want to make up for my “no-show” for the day with time with her that I could be spending on self-care. For example, if I have 20 minutes after work to go to the gym, I don’t do it, because I prefer to be with her. That’s something I’m working on in therapy and coaching, because if my cup is empty, I won’t have much to offer her when she needs it.

Anyway, that’s something that I think being a migrant has a lot of influence on, because if I had my mother here I wouldn’t feel so guilty or I would feel more support, I don’t know, besides it would facilitate many things like quality time with my partner, which is something that motherhood compromises because, since the baby’s father takes care of her during the day, when I arrive he needs to use that time for himself, to do the things he hasn’t been able to do all day because he’s taking care of her. Even though we have support, day to day it’s just the two of us.

Just like Eva, “Empoderadas” is already two years old. Tell me how the podcast came into your life.

In the middle of my pregnancy, I felt that creativity was beginning to blossom a lot in me and, since I was unemployed, in the free time I had I began to get involved with the production of a program for a friend of mine who was in Spain. At that time, I had been thinking for a long time about having my own podcast because I was a faithful consumer of that genre, I used them to train my ear in English and to learn about topics that interested me a lot, so based on the Influence of all these variables, I decided to take a leap and the first episode of “Empoderadas” premiered on July 18, 2020.

It was a way to feel useful, to also put myself as a priority and a strategy to not give myself over exclusively to motherhood, to find my identity in other fields.

In what ways is Cuba present in your daily life?

Daily. My husband is involved in activism so that the politics of relations between Cuba and the United States change, so that is also part of my daily life. But, in addition, Cuba is part of me; it’s in my identity and who I am. There is no way to not keep it in mind.

I always say that the term “Latina” doesn’t work for me, although here I always have to use it to apply to anything, but if they let me choose, I always choose to introduce myself as “Cuban.” Cuba pains me and I also celebrate with it everything that can be celebrated. Cuba runs through my veins and is very present in my life, including my podcast, a resource that has allowed me to weave a network that connects me with the island. In fact, when I went to Cuba in July this year, I was able to do a face-to-face event of “Empoderadas” with Cuban women entrepreneurs who live there, and it was a very special experience that connected me even more with my country. Also, I still have a lot of people there that I care about, my networks are full of news about Cuba, so disassociating myself from the island is not an option or even something I want.

Where is your home today?

Today I know that, although my village, my support network, is scattered throughout many parts of the world, it is also part of me, so I’m in all those places too. As I was saying, I don’t feel part of this place nor of Cuba when I return, that’s why since I emigrated things as simple as hanging photo frames in the house — which is something that makes you appropriate your space — unconsciously is difficult for me, because I see the places where I have lived as something temporary and I think that soon everything I see will no longer exist because I will have gone elsewhere.

In all this time that I have lived here I have moved many times and I have lived in three different states. I lived in Texas, Minnesota and California, and I think that nomadism has made me feel that this whole experience is temporary, that I don’t belong anywhere. That changed a little two years ago, when I had my daughter, who makes me feel that she is my home, not a place. My home is where Eva is.