The discussion on the economic crises in Cuba has various nuances and interpretations. A very common opinion among citizens is that, in a certain way, the country has experienced a permanent emergency since the beginning of the 1990s. For many families, the so-called “Special Period” is not something that was left behind after 1995, not even during the short-lived boom in the selling of medical services.

The economic collapse after 1990 markedly changed the contour of Cuban society. In recent years, a socio-structural framework has been formed where a process of social heterogenization is evident, which exhibits differences in terms of ownership, income and the type of work of individuals (Espina and Echevarría 2020).

While the GDP grew steadily (annual rates) until 2018, the transformation of the economic structure reproduced historical problems, adding new ones that have continued to negatively affect performance in recent years. Although the exportable offer has diversified, it is still concentrated in a few products. Emerging items have generated higher incomes, but have very weak linkages with the domestic economy.

Tourism has never achieved the pull that sugarcane agribusiness had, and medical services barely connect with other branches of production and services. At the territorial level, tourist activity has been concentrated in some destinations, while all the provinces had sugar mills. Likewise, once again a growing part of foreign exchange was placed under the umbrella of political agreements, concentrating trade in a few countries, specifically Venezuela and China.

The timid opening under the administration of Barack Obama and the interest in the new stage of “self-employment” as of 2010, led to a notable increase in the sending of money from abroad. These resources constitute a substantial part of the total income of many families and are also a source of seed capital for the establishment of new ventures. Remittances and income from tourism (tips and direct income from the private sector) are netted in a second stage through retail trade and control of the banking financial system. Even so, households are the direct recipients, which gives them a great capacity in their use and distribution. The typical Cuban household is less dependent on the state than it was in the late 1980s.

On the other hand, foreign investment, foreign credit and even international cooperation, while they are flows controlled by the authorities and executed by state entities, have determinants that go beyond the priorities established by the government or the economic cycle itself. To a large extent, they respond to strong conditioning factors related to perceptions about the prospects for the economy, trust in institutions, political stability, and ability to pay. In the specific case of Cuba, these perceptions are strongly associated with the progress of the “updating,” the central part of the island’s transformation in the last decade. In this period, the forecasts moved from optimism (boosted by the rapprochement with the United States) towards an evident pessimism and discomfort with the course of the “reform,” and, above all, with the few concrete results.

In another unfavorable turn, official data indicate that the rate of economic activity (corresponds to the proportion of the working-age population that has a job or is looking for work) fell by more than ten points between 2009 and 2017, only to recover partially later. In this last period, the numbers improved in the context of a reduction in the working-age population, as a result of emigration and other demographic variables. However, estimates from the International Labor Organization (ILO) are more conservative, reflecting that only 55 percent of working-age citizens are part of the economically active population (EAP), one of the lowest figures in Latin America.

In essence, the aforementioned aspects make up an economic structure characterized by a high degree of external dependence that significantly affects economic development; and the high risk that dominates international economic relations. At the same time, dependence has moved to homes. Some of the most dynamic activities for Cuban families’ income rely on transnational flows. Several decades of emigration and the increase in international mobility are beginning to be reflected in monetary and merchandise flows.

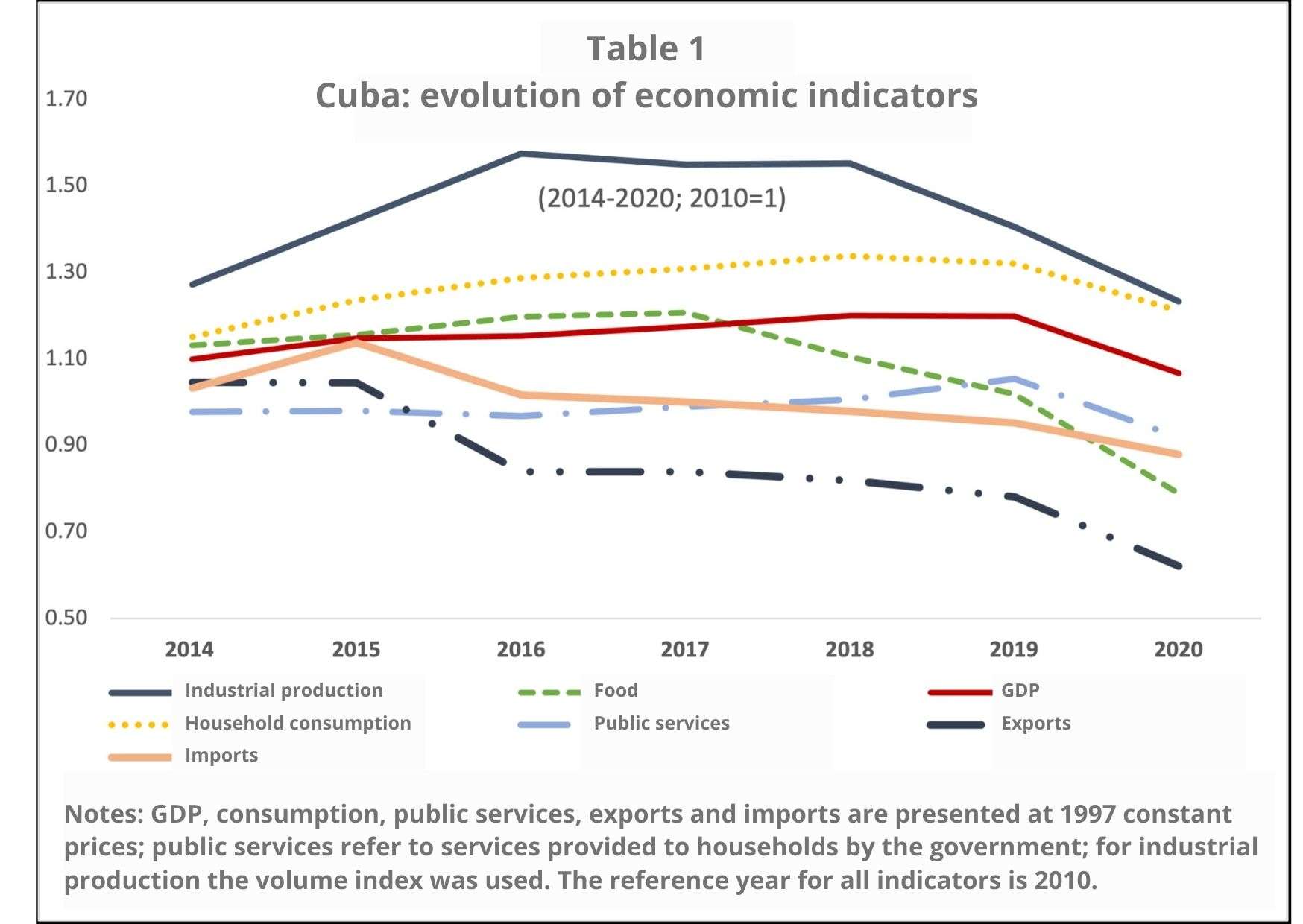

In the absence of a redistribution model tempered by another structural context, less control over employment and foreign exchange earnings, together with the stagnation in real terms of the resources for social services since 2010 (Table 1), imply that the State is no longer the guarantor of equity. The distribution of wealth in this new structure depends on other socioeconomic factors, which historically in Cuba have tended to reproduce inequalities.

New cycle of stagnation and recession

The slowing down in productive activity that began in 2014 is confirmed in the first instance in the figures for the external sector. Although this period includes the period of partial reconstruction of diplomatic and political ties with the United States, this did not prevent the progressive deterioration of the conditions of the Cuban economy. If anything, it delayed or masked it.

The analysis of the external context indicates that it was progressively hardening, based on a series of factors such as the decline of the Venezuelan economy, political changes in Brazil, Ecuador and Bolivia; the almost total reversal of Obama’s openings under the Donald Trump administration; less flexibility on the Chinese side in commercial and financial ties with that country; and more recently the position expressed in the negotiations with the group of Paris Club creditors; together with the interest of other creditors of the London Club in finding a solution for the outstanding debts.

The figures in Table 1 show a general slowing down in productive activity, with a high degree of synchrony. The reductions observed in exports and imports are of unknown magnitudes since the early 1990s. Import levels at constant prices are the lowest in at least twelve years, while individual services provided by the government have not reached such low levels since 2006. Household consumption in the market is at similar volumes to 2014. This panorama taken as a whole makes it possible to account for the level of a worsening of material conditions in the homes, whose magnitude exceeds that shown by indicators such as the gross domestic product. This is in a context of greater inequality and without the previous social policy protections. To this should be added the fact that the decline in the quality of public services is not adequately captured in the national accounts figures.

It is striking that this cycle contains an aspect that differentiates it from previous stages. The contraction in consumption is reinforced by the high dynamics shown by investments, particularly those related to real estate-hotel construction, and to a lesser extent infrastructure, a part of which has been concentrated in the Mariel Special Development Zone. The construction of hotels has maintained an increasing pace despite the fact that since 2017 the occupancy rate has been reducing, and the COVID-19 pandemic reduced the arrival of foreign visitors to insignificant levels.

The decline in production has been accompanied by a deterioration in key macroeconomic indicators, such as the fiscal deficit, inflation, and the exchange rate. The exchange rate in the informal market would have gone from an equivalent of 23 pesos per USD in July 2019, to more than 65 pesos per unit of the U.S. currency in September 2021. The price index (CPI) calculated by the ONEI indicates that these increased 18 percent in 2020, and 62 percent in the first eight months of 2021 (ONEI 2021). However, in both cases, there may be substantial undervaluations. The reason for this is that, due to the growing scarcity of basic products, these have much higher prices in the informal market, which tends to be under-represented in the calculation of this index. In practice, families have to go to it to access certain products, which are not available in other circuits. Unfortunately, in 2021 prices increased both due to the implementation of the “monetary reorganization” and due to the economic crisis, which has unleashed an inflationary spiral on the island. It is well known that inflation has regressive effects on income distribution.

Trends in Human Development Index

One of the most frequently used and internationally recognized indicators to analyze long-term development trends is the Human Development Index calculated annually by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). In the 2020 report, Cuba is ranked 70 out of 189 countries, in the category of “High Human Development-HHD.” This result places the island in ninth place in the Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) ranking and can be classified as very good, considering the whole set of unique circumstances surrounding Cuban development.

However, a more careful analysis reveals a much less favorable evolution in the last decade, which has a direct relationship with the perception of Cubans in general, and young people in particular, about progress and their perspectives in Cuba. The following considerations are grouped around four main elements.

The first, although in absolute terms, the Caribbean country exhibits progress in the global index and its three dimensions (health, education, and standard of living) since 1990, progress has been slower than in all comparable groups (world, LAC and HHD). As a consequence, the wide-ranging advantages in education and health that Cuba exhibited 30 years ago have been noticeably narrowed; while the historical income gap has widened even more. The intensification of contact with the outside suggests that these trends may sustain a perception of worsening living conditions and paralysis of development. Furthermore, between 2010-2019 the value of the HDI completely stagnated, which necessarily implies a relative deterioration with respect to the majority of other countries that maintained the high, even in the midst of a wide international dispersion.

Second, this trajectory is achieved in the context of a society whose levels of inequality have risen steadily. Although the HDI has introduced a methodology to recalculate the global indicator taking inequality into account, unfortunately, the absence of data has prevented it from incorporating the adjustment for the Cuban case. This is an aspect to take into account because the limited data available suggests a significant increase in inequality, which in turn would explain the fact that certain groups and communities have been marginalized even from the modest rates of economic growth achieved; and on the other hand, they suffer disproportionately the impacts of crises such as that associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

The debate on inequality and equity is often fierce in Cuba. The reduction of inequality until the 1990s is an achievement credited to the Cuban Revolution. However, the biggest problems are associated with the scarcity of internationally comparable data to determine where the island is currently located. The few statistics available indicate that the Gini index would have evolved from 0.22 in 1989 (Brundenius 1990), going from 0.41 in 1999 (Monreal 2017) to 0.45 around 2018 (Rodríguez 2019). Most experts would agree that income inequality has risen steadily, and that monetary income determines a growing share of total consumption. This is despite the fact that the universality and gratuitousness of basic social services soften the impact of this evolution (Echevarría, Gabriele, and others 2019). Although already in a very partial way.

A third aspect is that the indicators related to education and health are verified in a context in which there is a deterioration in their quality, together with problems of access to them by vulnerable groups and communities (Echevarría, Equidad y Desarrollo: oportunidades y retos para Cuba 2016).

Lastly, various experts have documented inconsistencies in the approach applied for measuring income in the Cuban case, taking into account the limitations of calculating the Gross Available Income in purchasing power parity. Some calculations using alternative methodologies suggest that the figures used by the UNDP in estimating the HDI for Cuba are overestimated, and show major variations throughout an incomplete series (Mesa-Lago 2020). As a consequence, the position in the ladder would be somewhat lower.

Problems of the moment

The health emergency derived from COVID-19 has had economic implications for all countries, but its impact is not symmetrical. During 2020, the island faced the negative external shock associated with COVID-19, with a productive activity weakened by the accumulation of domestic problems, the strained external environment and natural disasters. The impact of this emergency comes through multiple channels.

The economic contraction in the main economic centers pulls foreign demand down. Among Cuba’s 12 main trading partners, only China had positive growth in 2020. More than two-thirds of exports are directly related to health and people (medical services, medicines, tourism), which is why they have been hard hit by the reduction in international mobility.

The model for the selling of health services based on the sending of professionals took off in the Venezuelan market in 2005. Since its inception, it has been based on intergovernmental agreements. In recent years it has been criticized by governments and organizations with diverse approaches (Recio 2020); (Farber 2020). Tourism is a fundamental activity for the island. And it is also for many homes and small businesses. The closing of the borders has been devastating. Each closing month represents a loss of about $140 million. In 2020, the number of visitors fell by 75 percent, representing a decline from 1997 levels. Until July 2021, some 141,000 foreign tourists had traveled, 5 percent of the 2019 levels.

The closure of borders also severely affects the individual import of merchandise, one of the supply channels used by many ventures. Since 2013, Panama, Mexico, Guyana, the United States, Haiti and Russia have become very popular destinations. Total purchases were estimated to be between $1.5-2 billion annually (The Havana Consulting Group 2021). Between 2013 and 2019, trips abroad by Cubans residing on the island increased more than two and a half times.

Cuban emigrants have traditionally been considered to be very loyal to their families, but massive unemployment in the United States, where the vast majority of that diaspora lives, will have an undeniable impact. For example, The Havana Consulting Group (a Miami-based business consulting firm focused on the Cuban economy) estimates 20-30% drops in flows (The Havana Consulting Group 2021). Informal channels have also been affected by the closure of airports for several months.

The above panorama is completed with the effects derived from the restrictive measures implemented to control COVID-19. It should be noted that the impact of confinement and other similar measures is asymmetric throughout the economy. In this sense, the most severe effect is seen in the service sector, which depends disproportionately on the interaction and movement of people.

In the first half of 2021, the performance of the fundamental sectors was well below forecasts, although some lines such as nickel and telecommunications services performed well. According to the authorities, Cuba’s GDP contracted by 2 percent until the end of June 2021. This extends the economy’s drop to eight consecutive quarters, counted from the third quarter of 2019. The beginning of the recovery of tourism did not materialize and the sugar harvest has the worst result in more than a century.

The data disclosed on investments makes it difficult to determine their dynamics, due to the lack of a uniform basis for comparison after the exchange rate reform. However, two recent trends are reinforced. Havana now represents 70% of the total, while real estate projects (essentially associated with tourism) account for half of what was invested.

The evolution of the health situation has also been unfavorable, which compromises the recovery. Since mid-January, restrictions have been tightened to contain the worst outbreak since the beginning of the pandemic. During 2021, each month has been worse than the previous one. In all of 2020, the accumulated cases reached 12,056 infected with COVID-19. However, between January and July 2021, that number multiplied by twelve, reaching a total of almost a million cases at the end of October 2021. This was in the midst of an acute shortage of medicines, and the visible collapse of the health system in certain provinces of the country. The island has managed to produce its own vaccines, but the start of mass immunization did not come in time to prevent the impact of the Delta variant. Between May and August 2021, Cuba has had some of the worst numbers in the Americas and the world.

The monetary and exchange rate reform, towards the end of the first semester, has not improved the macroeconomic and general business environment, as a consequence of design and implementation errors, together with the inability to promote structural reforms related to the state-owned enterprise, and the private sector. According to the ONEI, until August prices had grown an average of 63% compared to 2020, but they would have almost doubled for food, and almost tripled for transportation.

Additionally, during 2021 the tensions in the national electricity grid worsened. The combination of postponement of maintenance, shortage of spare parts and fuel, led to an increase in the very “unpopular” power outages (blackouts). The outages have been extended by up to 8-10 hours on a daily average in some areas, with reports of longer lapses due to unforeseen breakdowns. The public’s perception is that the distribution is not homogeneous between the areas of the country. Some neighborhoods in Havana are more protected than several other provinces, for example.

The authorities had set a growth target of 6% in 2021, and a similar forecast for 2022, with the aim of recovering the activity levels of 2018 (in 2019 GDP contracted by 0.2%). However, the results obtained in the first half of the year indicate that this goal will not be met. The possible scenarios depend critically on the beginning of the recovery of international tourism, the control of the pandemic associated with mass vaccination, and the relaxation of some U.S. sanctions linked to remittances and travel.

The political cost of the reform’s paralysis

It has been a decade since the economic reform was accepted at the highest political level, nominally at least, but its implementation went from bad to worse. Documents were adopted at the 6th (2011) and 7th (2016) Congresses that should serve as the basis for the transformation of the economic model. Against all odds, since 2016 practically nothing new was implemented until the end of 2020 when the authorities were already overwhelmed by the economic crisis. An attempt was made, between 2017-2018, to go back in areas of wide resonance for citizens, such as self-employment.

Few reforms are more urgent and justified than the Cuban one. It is no secret that the Cuban model has for decades failed to achieve decent economic performance. The brief periods of economic dynamism have been associated with generous external compensation. It was thus in some years of the Soviet accompaniment, and as a result of the ephemeral impulse of the exports of medical services to Venezuela. Achieving a productive economy would significantly increase the chances of maintaining the country’s independence and would increase the cost of U.S. economic sanctions.

The economic reform stagnated as a result of ideological lags, political calculation, strong vested interests, and a shortage of capable technical personnel in the public sector. Already since the beginning of the century, the reluctance to make the necessary domestic changes led to once again placing a majority part of foreign trade under political agreements. Venezuela’s economic problems are now translated into a liability for the island. Certain conservative circles have been very adept at using the spaces and legitimacy of public institutions to criticize, sometimes underhandedly, the economic reform. Of course, without offering another alternative than the current model and resistance, terms that have less and less echo in vast sectors of Cuban society, particularly young people. It is not so strange that, given the lack of progress in Cuba, recent emigrants have been one of the most solid bases of the hardline policies advanced by the Donald Trump administration.

The above errors and omissions have been exacerbated by the complexities of political change. Most of the structural factors that explain the general features of the Cuban model have radically changed: political leadership based on charisma and historical legitimacy; the existence of foreign partners capable of offering generous financial assistance; relative homogeneity of the Cuban population on account of the reduced inequality and dominant ideology; and relative economic isolation from the rest of the world as a result of U.S. sanctions.

The trends described in the essay show a profound transformation of the Cuban economy and society since the early 1990s, which are expressed in the first instance in families, their priorities and life projects to face a hostile context. The “updating” could have been the way to get the Cuban model tempered to new conditions. Its failure suggests that the gap has widened.

Conclusions

The weak economic growth and the accumulation of social debts point towards the sustained deterioration of the material bases of well-being. This goes beyond the losses associated with the COVID-19 cataclysm, or even the latest Trump administration sanctions, but rather a long-term process of worsening these conditions can be identified. Additionally, economic problems affect more certain groups and communities, the so-called “barrios” are home to some of the humblest sectors of Cuban society.

In a context of an increase in the trend of economic inequality, the “updating” was more effective in containing social spending than in improving economic dynamics, which contributed to widening historical gaps. The transnationalization of Cuban households made them vulnerable to the sudden interruption of financial flows and travel as a result of U.S. coercive measures and COVID 19. The expansion of the informal economy reinforces previous trends and accentuates the lack of job protection. At the same time, it denies the fiscal resources necessary to correct these imbalances. In this scenario, the palliative instruments and resources available to the Cuban State are inadequate and insufficient.

In 2021, Cuba has experienced a perfect storm, in economic terms. Its traditional sources of income have been diminished, the reform that did not occur in time has not been able to mature, U.S. sanctions have increased, COVID 19 has wreaked havoc, and the external environment is extremely adverse. The visible effects of this context — shortages, blackouts — now find fertile ground in a new generation for whom the “achievements” of the Revolution have faded or are almost imperceptible. The challenge of economic recovery now collides with a domestic scenario of greater political instability. Unfortunately, the Cuban political system is not well equipped to meet these demands.

Sources consulted:

Brundenius, Claes. 1990. “Some reflections on the Cuban economic model.” In Transformation and struggle: Cuba faces the 1990s, by Sandor Halebsky and John M Kirk. New York: Praeger.

Echevarría, Dayma. 2016. “Equidad y Desarrollo: oportunidades y retos para Cuba.” New School-Casa de las Americas course. Havana: Casa de las Américas.

Echevarría, Dayma, Alberto Gabriele, Sara Romano, and Francesco Schettino. 2019. “Wealth distribution in Cuba (2006–2014): a first assessment using microdata.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 361-383.

Espina, Mayra, and Dayma Echevarría. 2020. “El cuadro socioestructural emergente de la ‘actualización’ en Cuba.” International Journal of Cuban Studies 29-52.

Farber, Samuel. 2020. “Cuban Doctors Abroad-Appearances and realities.” New Politics, May 30. www.newpol.org/cuban-doctors-abroad-appearances-and-new-realities.

Mesa-Lago, Ricardo. 2020. “Vidal’s Results and Cuba’s Ranking in the Human Development Index.” Cuban Studies (49): 119-128.

Monreal, Pedro. 2017. Rebelion. https://rebelion.org/estamos-teniendo-en-cuba-una-conversacion-equivocada-sobre-la-desigualdad/.

ONEI. 2021. “National Office of Statistics and Information.” September. www.onei.gob.cu.

Recio, Milena. 2020. “Diplomacia médica cubana: oportunidades durante la pandemia.” Esglobal, May 27. www.esglobal.org/diplomacia-medica-cubana-oportunidades-durante-la-pandemia.

Rodríguez, José Luis. 2019. “Intervención en panel de Ultimo Jueves.” Temas magazine.

The Havana Consulting Group. 2021. Havana Consulting Group. September. http://www.thehavanaconsultinggroup.com.

***

Note: This article was originally published on American University. OnCuba is reproducing it with the express authorization of its author.