In January 2025, the Dominican Republic received 1,155,484 tourists ― 395,555 of them cruise passengers ― 22% more than in 2024. In the first quarter, the country received 3,348,716 visitors (a 4% increase compared to the same period in 2024) and achieved an 81% hotel occupancy.

In 2025, the main countries sending tourists to the Dominican Republic were the United States (36%), Canada (25%), Argentina (8%), Colombia (5%) and France (3%).

Meanwhile, in those first three months, 571,772 international visitors arrived in Cuba (71% of the total in 2024). The main source of visitors came from Canada with 272,274 (68.2% in 2024) and a 47.6% participation; Cubans residing abroad with 59,896 (80% in 2024) and a 10.4% participation; the United States with 39,447 (84.4% in 2024) and a 7% participation of total visitors; and Russia with 33,395 (50% in 2024) and a 6% participation of the total.

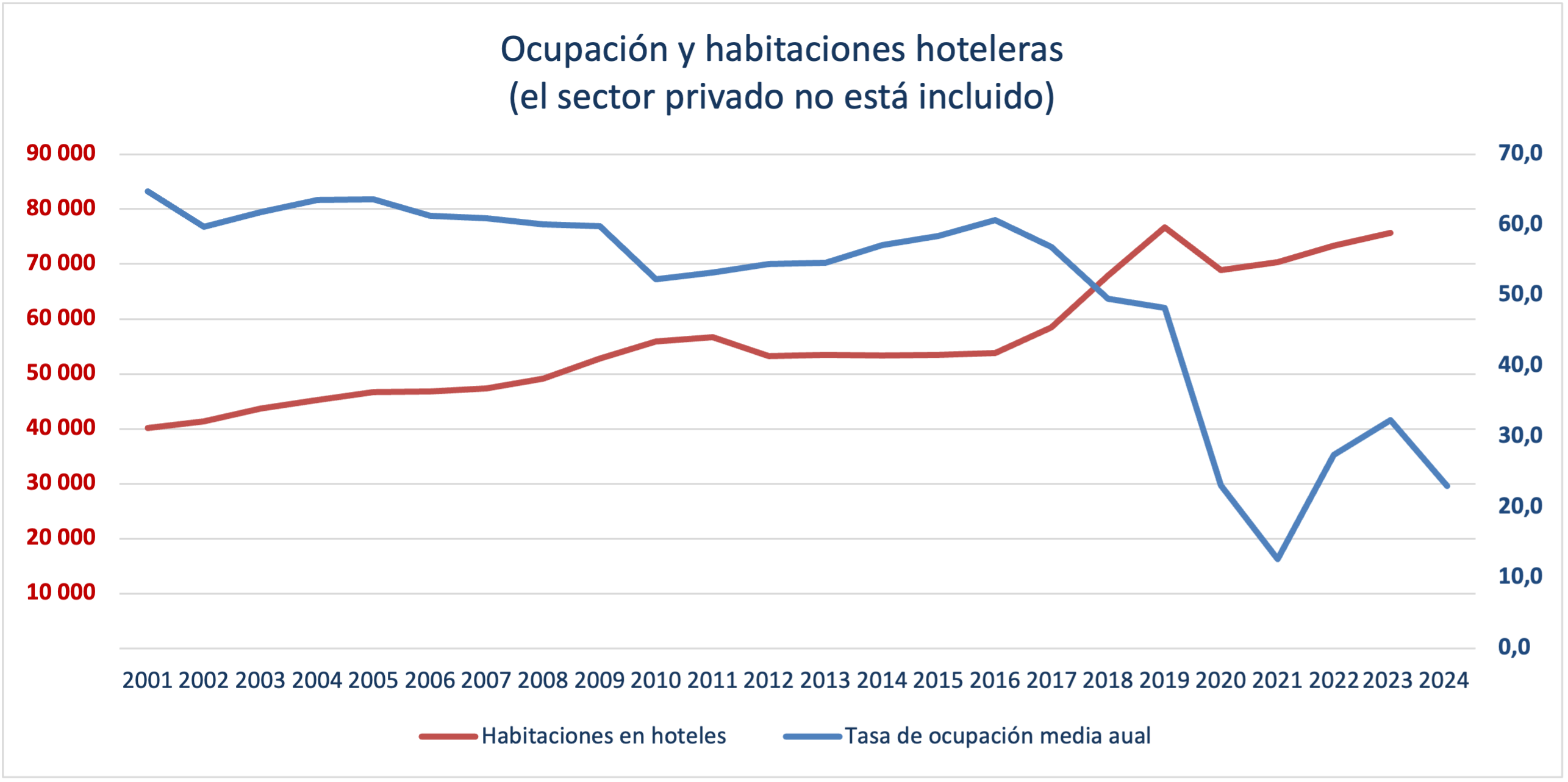

According to the Cuban Statistical Yearbook, completed in 2023, there were 86,559 physical rooms in the country across all types of facilities, not including rooms in the private sector. By the way, why aren’t they included? Aren’t they part of the tourism sector?

Of these rooms 81.7% were concentrated in 5-, 4-, and 3-star hotels. Considering that some hotels were completed in 2024 and that the new hotel on K and 23 was added in these first four months of the year, the number of rooms must have grown somewhat.

The average annual occupancy rate in 2023 was 31.7%. In 2024, it dropped to 23%. A lower occupancy rate is expected in the first quarter of 2025, given the increase in the number of rooms and the decrease in the number of visitors.

The graph above summarizes one of the greatest contradictions facing the sector today: maximizing tourism revenue with a room surplus that has been accumulating idle capacity for more than twenty years and that, even in the peak years of tourist arrivals (2015-2018), has never managed to consistently exceed 60% occupancy.

The Cuban tourism sector faces multiple challenges, some external to the sector and even to the country, and others definitely internal.

Although it is obvious, I will emphasize that all strategies and policies adopted will be suboptimal because the blockade and the Trump administration’s policies condition/limit/hinder Cuba’s participation in this “business” on equal terms with its competitors. Let’s consider the blockade as a negative parameter and focus our efforts on reducing its effects. The challenges are multiple.

A first challenge would be the competition and existing competitors in the region, who today enjoy the same natural advantages and surpass us in almost everything, from advertising campaigns to “non-hotel amenities.”

For the purpose of illustrating this point, some of these amenities, which are external to the sector, are detailed below.

- Airport infrastructure and airport services: The lack of investment to modernize our airports and improve services means that the first impression, and also the last, is not the best. The tourist ordeal begins at the airport.

- Car rental: In Cuba, car rental for tourism remains a state monopoly, and its prices are at least four times those of other destinations. In destinations that compete with Cuba, rates can be found ranging from 5 USD/day to 30 USD/day in places like Cancún and as of 14 USD/day in Santo Domingo. There are also dozens of companies that provide the service and compete with each other.

- Public transportation: There is an almost total lack of transportation within Cuba’s cities; public train service is poor quality and indeterminate in frequency. Few opportunities to travel from one province to another, high prices, poor quality buses. Limited frequency and destinations for domestic flights. And the deplorable state of the roads turns a road trip into an adventure.

- Architectural deterioration and increasing unhealthiness in several cities, including Havana.

The second major challenge also does not depend on tourism and is associated with macroeconomic imbalances and exchange rate distortions. Although tourists may “enjoy” the experience of our multiple exchange rates, those who suffer most from exchange rate distortions are hoteliers, forced to submit a food budget sometimes calculated in two different currencies and at an exchange rate that does not benefit them.

The devaluation of the Cuban peso (CUP), which should act as an incentive for exports, makes imports more expensive and adds a little more spice to hotel or private restaurant management. Once again, the tourism sector here depends on “external factors.”

Competition also has an advantage in terms of input costs. Purchasing products in foreign markets costs Cuba more, not only due to the direct effect of the blockade, but also due to the increasing difficulties in servicing debts, which have been consolidated in recent years and which add points to Cuba’s “country risk.” It must be said, once again, that the tourism sector is not the ultimate culprit for this.

The country’s weak productive structure; the limited capacity of the majority of domestic enterprises to “produce for tourism” in the necessary volumes and quantities and at prices that are competitive with imported goods; and the lack of credit or other forms of financing that these enterprises suffer from, all stand in the way of the goal of “recovering tourism.”

To truly make tourism one of the driving forces of the national economy, much more than wishful thinking is required.

Without a doubt, “the recovery of Cuban tourism requires a bold strategy” that will address the challenges outlined above and many others.

Among the measures the government announced during the recent Tourism Fair are:

- Updating the regulatory framework to encourage foreign investment;

- Allowing new business models, such as leasing tourist facilities, and facilitating operations in foreign currencies (dollars, euros, Canadian dollars);

- Launching new air routes;

- Eliminating the health tax at airports, ports, and international marinas;

- Creating public-private partnerships with self-employed workers and diversifying the tourism product.

However, it would be beneficial if this strategy focused on completely freeing hotels from the heavy burden of the employment agencies of the Ministry of Tourism (MINTUR) or Gaviota, to make the service these agencies provide an option for hoteliers.

In this way, tourism workers could receive the income they deserve for the quality of their work and at the discretion of hoteliers.

These measures should be preceded by concrete actions to settle the debts still owed to foreign companies in the sector, or at least begin that process.

These “structural reforms” should allow hotels and hoteliers to import directly if they so choose. They should also allow direct and effective payment in foreign currency to national producers — until we resolve our monetary problem — whether state-owned or private. And that the money earned by these producers be respected and not turned into salt and water via freely convertible currency or Cuban peso.

These reforms should allow hotels and hoteliers to buy where prices and quality are best and not force hotels to buy from national enterprises, sometimes at higher prices and lower quality.

They should also promote budget discussions taking into account the dynamics of international and national inflation.

Hopefully, the reforms will lead to considering the profitability of the hotel bill as a decisive factor in decision-making, rather than revenue growth.

They should lead to concentrating activity in those hotels/destinations that can offer a service competitive with the standards of our region.

They could promote productive development policies that can produce competitive goods and services for our tourism sector.

The country’s municipalities, within this strategy, should be able to develop their own strategies for promoting tourism, their tourism, and the ministry should allow them to do so.

It wouldn’t be a bad thing if the reforms led to the unification of the management of the tourism sector into a single institution. And at the same time, they would sweep away the centralized management that our tourism sector suffers today, recovering the spirit of that ministry we had thirty years ago and that performed the miracle of placing Cuba on the map of the tourism market in the Americas and the world.

Cuba, despite the blockade and our own actions, is and will be a tourist destination, due to its geographical location in the southern part of the northern hemisphere, its territorial dimension in this Caribbean of small islands, the richness of its history and the quality of its beaches, its people…because there are still many good Cubans.

It would be terrible if the same thing happened with this “strategy” as happened with the 63 agricultural measures and the 93 designed to recover sugar production. And paradoxically, they have reminded us of the famous phrase of the bus driver: “Move back, comrades.”

Tourism is not a watertight compartment, separated from the rest of the Cuban economy and society. Quite the contrary, it depends on the entire economy to function properly.

Today, the sector internalizes the weaknesses of our economic functioning and pays for it in profitability, competitiveness, and its ability to drive the country forward.

Undoubtedly, someone is placing their honor at stake in the recovery of tourism, but restoring the dynamics of tourism activity is much more than a matter of honor.

what has been said is all true but you need to bring in live chickens and hens and resupply both meat and eggs in Cuba to start to show you are really on the path to recovery