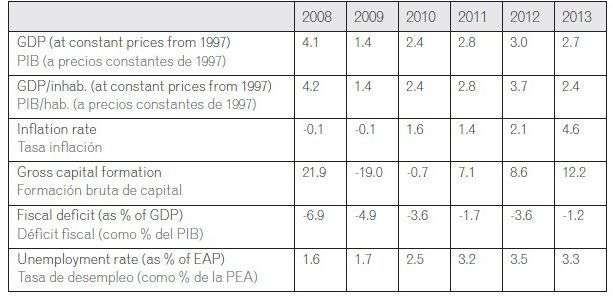

The evolution of the Cuban economy in recent years has been influenced by several processes: the international economic crisis; the application of the “Economic and Social Policy Guidelines” which sum up the changes are taking place in the country’s economic system; and the intensification of the U.S. economic, commercial and financial blockade. In this context, Cuba’s GDP growth rates are insufficient and, as of 2013, have shown a tendency to stagnate 20131 (see table 1). During the first semester of this year, this “growth” was just 0.6 percent.

Clearly, without sufficient growth rates of at least three percent, all of the country’s goals will remain indefinitely postponed. The Cuban economy’s open character and its external dependence means that the evolution of the external environment is always key to explaining problems and challenges facing the country’s own evolution; moreover, the external environment in many cases determines the country’s future prospects.

Therefore, to avoid making errors, or even worse, making the same errors over and over, it is essential to analyze the challenges facing Cuba’s trade and insertion in the international economy.

According to the country’s 2012 Statistical Yearbook, Cuba’s rate of opening has increased perceptibly since 2007, rising from 38.0 percent of the GDP to almost 46 percent in 2012.2 In addition, we should take into account that in Cuba, any variation of the GDP has entailed higher- than-proportional changes to imports (for every one percent rise in the GDP, imports have risen by about 2 percent) Imports continue to be replaced by national products at a weak pace, and the transformation capacity of the country’s domestic production for exports is still low.

Source: ONEI. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba, 2012, Havana. Panorama Económico y Social de Cuba, 2013. Abril 2014 edition.

This is seen in the limited response by national production to external opportunities, such as those presented in the most recent period.3 In short, imports are few and no real options exist for replacing imports with national products, which determines Cuba’s chronic deficit in the balance of goods.

However, its overall foreign trade balance (see appendix 2) since 2009 has tended to show a surplus, determined by a significant surplus in the net export of professional services to various developing countries, especially Venezuela, in line with cooperation agreements with these countries.

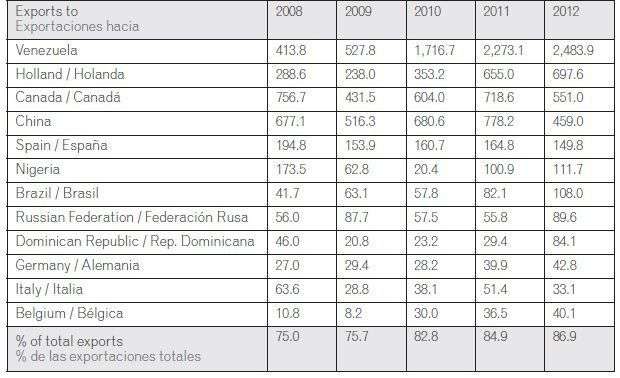

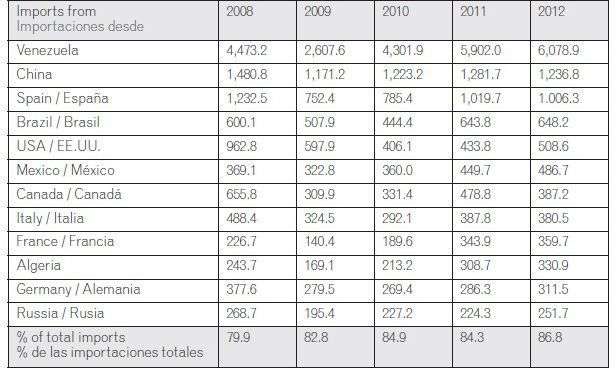

However, Cuban cooperation in the form of professionals (not just in the medical sector) exists in more than 60 countries. Cuba’s top 10 trade partners—in terms of total foreign trade of goods—are Venezuela, China, Spain, Canada, Holland, Brazil, Mexico, the United States, Italy, and France, in that order. Its top three trade partners accounted for 45.7 percent of Cuba’s total foreign commerce in 2007, and by 2012, those three countries had increased that participation to 58.9 percent of the total.

Source: ONEI. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba, Havana, 2012.

Source: ONEI. Anuario Estadístico de Cuba, Havana, 2012.

The Venezuelan market is the main destination for Cuba’s external sales and the most important supplier of goods to Cuba. In 2007, total trade with Venezuela represented 19.6 percent of Cuba’s foreign trade in goods, but by 2012, that figure had risen to 44.2 percent.4 For the 2008-2012 period, the Venezuelan market absorbed an average of more than 35 percent of exports, almost doubling the relative weight of the Dutch and Canadian markets, the second and third most important destinations of Cuban exports. In terms of imports, Venezuela was also Cuba’s most important partner between 2008 and 2012, supplying an average of 32.6 percent of all Cuba’s imports.

The importance of Cuba’s relations with Latin America and the Caribbean, especially with its strategic partners in and outside of the region, is far from any reasonable doubt. Equally decisive is the country’s policy of maintaining and promoting relations with other regions for economic reasons, and to consolidate diverse relations and avoiding the mistake of over-concentration, such as was the case of the now- defunct Eastern European socialist bloc.

Hence, the exceeding importance of negotiations with the European Union (EU) for the Cuban economy and the rearticulation of its foreign economic relations in the immediate future. Despite the crisis, trade with the EU represents more than 20 percent of Cuba’s total export and import of goods, and about 22 percent of its income from tourism, given that a large part of joint investments and business with foreign companies involve European partners. In addition, according to EC data, since 2008 more than $80 million has been channeled as development aid from the EU to Cuba.4

A number of problems are limiting the necessary adequate functioning of Cuba’s external sector, including a very high level of centralization in foreign trade operations, directly related to limited margins of business autonomy that do not promote a direct connection between national producers and the international market; restricted access to international financing; markedly distorted relative prices, to a great extent as a result of the effects of the overvaluation of the Cuban convertible peso (CUC) and the dual currency system; deterioration of the physical infrastructure related to foreign commerce (ports, roads, airports, storage capacities); and no less importantly, the inadequate network of specialized support services for the export sector (telecommunications, Internet access, legal consultants and technical assistance).

Beyond objective structural limitations, creating a more diverse and dynamic Cuban external sector will require changing the operations of a system that is highly centralized, and proceeding to decentralizing foreign trade operations, enabling productive entities and small and medium size businesses (state and non- state) to begin to have direct relations with international markets. This would make it possible to bring about more active participation by Cuba in international flows of direct foreign investment (DFI), which can improve the export capacity of existing enterprises in Cuba, fostering their participation in chains of value and contributing to provincial and local development.

These foreign investments are key to accessing advanced technology, incorporating modern management methods, stimulating innovation in Cuban personnel development and training, generating effective links with domestic productive sectors, and definitively turning around the acute process of decapitalization to which the domestic economy has been subjected.

Obviously other, fundamental elements of policy exist for making the Cuban economy and its external sector more dynamic. Particularly notable is the need for a banking system that carries out its functions and fosters a credit policy with the necessary conditions for promoting the financing of foreign trade operations by Cuban companies, especially small and medium size enterprises (SMES).

International experience confirms the creation of certain financing methods for strengthering foreign trade operations that are not used or, at least, not sufficiently. It is worth asking what has been the experience of the SUCRE mechanism and its accounting unit (the sucre), and why the participation of Cuban enterprises has become marginal in a structure that emerged as part of the ALBA bloc. Once again, objective factors combine with subjective ones that are burdened by inertia; the losers are the economy and the Cuban people.

Note:

1 In general, the growth rate of economic activity in Cuba between 2008 and 2013 has been much lower than that noted in the majority of Latin American nations during this period.

2 According to ONEI, the rate of external opening is calculated as the amount of commercial exchange of goods and services with foreign countries, divided by the GDP.

3 En 2010 los precios mundiales de níquel y azúcar superaron las cifras inicialmente previstas, pero las producciones físicas cubanas no lograron alcanzar los volúmenes planificados, por lo que el país no fue capaz de beneficiarse de esa coyuntura favorable (intervención de Marino Murillo, vicepresidente del Consejo de Ministros y Ministro de Economía y Planificación, en el VI Período de Sesiones de la Asamblea Nacional del Poder Popular, diciembre 2010).

4Datos sobre peso de la UE en comercio y turismo cubano obtenidos a partir de información estadística de la ONEI. El dato sobre la cooperación europea hacia Cuba, fue tomado de Granma, 1 de mayo de 2014, p. 4.

The Export Import Data levels are based on actual and authentic shipment. In the shipments the records are used where the content is filed along with the customs later it will immediately alert when the potential and opportunities have threats. In India the Seair Exim Solutions’s is used for import Data where it acts as source in order to get the detailed understanding about the rivals on the regular and daily basis. https://www.seair.co.in/