At a time when it would seem that Cuba is approaching the “peak” moment of the COVID-19 health emergency, attention is likely to start shifting towards managing the economic recession that the country has entered in 2020 with an estimated decrease in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of between 3.7 to 4.7%. (1)

The economic measures adopted to mitigate the economic impact of the COVID-19 could be maintained for some time, with possible adjustments, but it is the measures related to promoting the economic recovery that should occupy the spotlight.

This has not been a “normal” economic crisis and, consequently, one would not expect a “normal” recovery either. The recession is not primarily due to a “failure” of demand but to a “supply shock.”

The Cuban government had to take deliberate action to stop the operation of the economy―as in many other countries―since social distancing measures required interrupting a relatively large part of production and services. Supply and capital flows from abroad have also been affected, which have had the effect of “disconnecting” circuits from the national economy.

The economic recovery in 2021 should take place progressively and unevenly across sectors. Tourism, which from “locomotive” became an “accelerating” factor of the recession, is likely to function as a “retarding” factor of the recovery because there is no glimpse of a safe and substantial revival of tourism flows in 2020 and 2021.

From an economic policy point of view, in a recovery it would be reasonable to pragmatically use any asset that may be available in Cuba.

The argument that I have made in recent days on social networks is that the private sector is one of those assets, but that its use would require the legalization of the operation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

I have also argued that a positive contribution by SMEs to the recovery process could have the effect of making them part of the “new normal” of a post-COVID-19 Cuba.

What could be expected from SMEs in the short term?

Expressed succinctly, SMEs could be the best opportunity to increase productivity in the short term and thus help the economic recovery.

In other words, these are processes at the level of employment and productivity, an essential aspect where discussions between economists often begin and end. These are the two factors to which special attention should be devoted.

SMEs could increase job creation in the private sector, precisely the only sector that has increased net employment in Cuba since 2008, but which has been limited due to the restrictions with which self-employment has to operate.

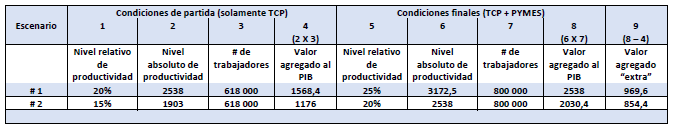

*Caption:

Cuba: State and non-state employment (thousands of workers)

State employment Non-state employment

In 2019, the state sector only retained 75% of the workers it employed in 2008, an annual average “destruction” of 2.6% in net employment.

On the other hand, the non-state sector increased net employment at a rate of 4.9% per year, reaching 31.8% of national employment in 2019, almost a third.

The private sector plays the essential role of creating net employment in Cuba…for a long time

The official statistics of private employment lost rigor as of the Statistical Yearbook of 2017 and therefore it is preferable to make estimates as of 2016 instead of using the distorted data from the official statistics. I have addressed the issue in a previous article. (2)

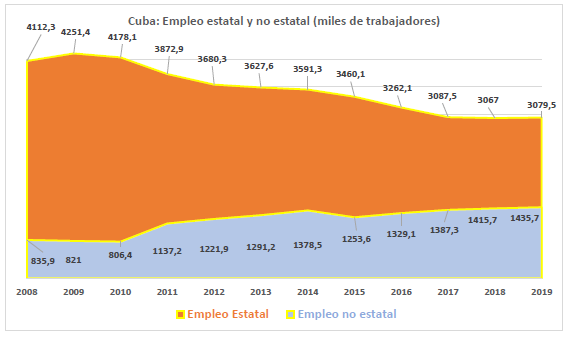

The following graph indicates that from 2008 to 2018, private employment (the self-employed and private agricultural producers) has represented the majority of non-state employment, reaching 86% of total non-state employment in 2019. I explain in a final note the method used to estimate the total figures for private employment, non-self-employment private employment, and cooperative employment in 2017 and 2018. (3)

The private sector added 617,400 workers between 2008 and 2018, occupying the important role of net job-creating sector of the economic system.

During the same period, the cooperative sector (UBP, CPA and CNA) contributed 54,600 net jobs, eleven times less than the net employment added by the private sector.

In 2018, the private sector contributed 27.2% of the country’s total employment.

*Caption:

Cuba: Forms of non-state employment 2008-2018 (thousands of workers)

Non-state employment Cooperative Private Self-employed Non-self-employed private

In addition to accelerating job creation, SMEs could increase the average productivity that self-employment has today. It is known that the enterprise format offers technical-productive advantages over the ambiguous scheme with which self-employment operates today, something that in “the form” would seem to be a modality of individual and family work, but that allows the hiring of employees, although national private enterprises are not legally recognized.

Further strengthening of net job creation and increased productivity would require the legalization of SMEs to be accompanied by the elimination of the nominalized (narrow and primitive) licensing system that prevents the deployment of the technical capabilities of part of the self-employment labor force, that is to say, it is necessary to overcome a “planning” that leads to the deliberate underutilization of the country’s main productive resource.

Under conditions in which the state sector has substantially reduced employment, private SMEs should offer jobs that reflect not only the diversity of the country’s economic structure, but also intensive activities in knowledge and technology.

The importance of data on private employment is that when it acquires a large scale, it becomes a crucial variable in the country’s productivity and therefore in the process of creating added value.

By having a large scale, productivity increases in private employment have a significant effect on the national economy.

With this “critical mass,” any notion that the private sector is a kind of “gutter” where the workforce subject to conditions of low productivity will end up to offer peripheral products and services, is a clueless notion regarding the reality of the Cuban economy and society.

From the moment in which the private sector offers almost a third of national employment, any “commoner” approach of the private sector is wrong. To put it in current codes: it would be a “unlocking” of economic thinking that is needed to overcome the crisis.

Could the contribution of the private sector to economic growth be estimated in the context of a possible recovery?

As the main argument that I have used to defend the accelerated establishment of SMEs in Cuba rests on the combination of the number of employees and the increase in productivity, the component that would remain to be quantified would be the one related to productivity.

It is a complicated exercise since it cannot be directly supported by official statistics and there do not seem to be any specific studies on the subject either. At least I couldn’t find them.

It would then be an approximate exercise that would use, as a reference, the information on relative productivity in other countries and that instead of offering unique estimates, would present a range of estimates. This estimation exercise is not aimed at precision, but at approximation.

An analysis carried out in Vietnam indicates the differences in productivity that exist depending on the intersection between the form of economic management and the institutional format of the productive entities, comparing the productivity in four types of activities: (4)

- State enterprise

- Private SMEs

- Legalized “home businesses” (where there is no employer-employee relationship, but individual and family work)

- Informal activity

When the absolute productivity averages of each of these levels are compared, it is possible to calculate relative figures of productivity. In the aforementioned study, the figures are as follows:

The average productivity of private SMEs is equivalent to 38% of the productivity of state-owned enterprises.

The productivity of “home businesses” is equivalent to 81% of the level of productivity of SMEs and 30.9% of the productivity of state-owned enterprises.

The productivity of informal activity is equivalent to 43% of the productivity of SMEs and 16.5% of the productivity of state-owned enterprises.

In other words, the data from Vietnam allow us to identify a “hierarchy” of productivity levels which we assume could approximately exist in Cuba in general terms.

The method for estimating the effect of SMEs on the productivity of the non-agricultural private sector

The data from Vietnam serve as a reference to establish various assumptions of the exercise that is carried out to estimate the possible effects on productivity in the event of the eventual establishment of SMEs.

Only two levels are considered under Cuban conditions: the self-employment sector that already exists and the SMEs that have not been legally established.

The absence of data forces us to work with “thick” assumptions, the main one being the consideration of a “medium” situation at both levels (self-employment and SMEs). Naturally, there is great diversity within the Cuban self-employment sector, which, in fact, includes the operation of SMEs, even if they have not been legally recognized.

What we want to measure approximately is the effect that the establishment of SMEs would have on the overall average productivity of the workers that today legally participate in the self-employment sector and of the additional workers that could be incorporated, both in the SMEs and in the self-employment sector, in a new context in which both modalities would coexist within the national private sector.

It is important to clarify that the estimation exercise considers that only part of the self-employment sector would be transformed into SMEs and that the effect on the productivity of SME workers was not being measured, but rather the effect that SMEs could have on the average productivity of all the workers that make up the self-employment sector + SMEs conglomerate, that is, all the non-agricultural private workers.

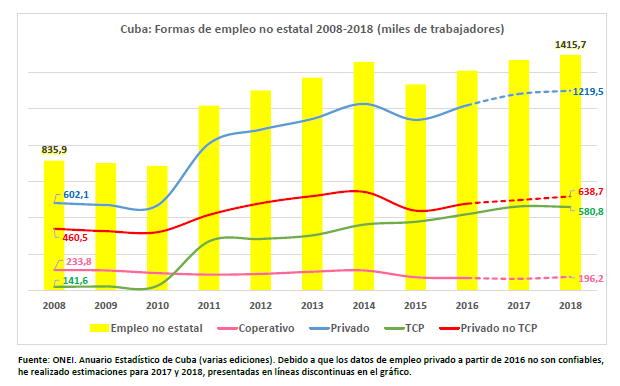

Two scenarios:

Two scenarios are considered. The first assumes that the current average productivity of the self-employment sector is equivalent to 20% of the country’s average productivity and that the legalization of SMEs would raise that level to 25% of the national average productivity.

The second scenario considers lower start and finish levels of productivity. It is assumed that the current level of productivity of the self-employment sector is 15% of the average productivity and that the establishment of SMEs would increase the productivity of private non-agricultural employment to 20% of the average productivity.

As can be seen, these are moderate assumptions that move in ranges that are even lower than the relative level of productivity observed in Vietnam, where the productivity of “home businesses” is equivalent to 30.9% of the productivity of state enterprises and SMEs represent 38% of the productivity of state enterprises.

The starting data:

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2019: 57.31 billion pesos (estimated based on growth of 0.5% and from GDP data at constant prices in 2018) (5)

Total number of workers in 2019: 4,515,200 (6)

Average productivity in 2019: 12,692 pesos (rounded figure: 12,690 pesos) (7)

Total number of workers in the self-employment sector in 2019: 617,974 (data at the close of September 2019) (8)

Adopted assumptions:

- Only employment in the self-employment sector has been considered as starting data (based on the number of licenses reported at the end of September 2019).

- It is assumed that the legalization of SMEs would produce an average increase in the productivity of all the workers in the private non-agricultural sector (self-employment sector + SMEs).

- It is assumed that the current productivity levels of the self-employment sector are so low that it is feasible to register relatively high increases in the indicator in the short term, even though the new average productivity at the point of arrival (after establishing SMEs) remains relatively low.

- It is assumed that the establishment of SMEs would facilitate the increase of private non-agricultural employment to a level of 800,000 workers in six months (employment in self-employment sector + SMEs).

Estimate summary:

*Caption:

Starting conditions (only self-employment sector)

Final conditions (self-employment sector + SMEs)

Scenario

Relative level of productivity

Absolute level of productivity

# of workers

Value added to the GDP

Relative level of productivity

Absolute level of productivity

# of workers

Value added to the GDP

“Extra” value added

Estimation results:

Scenario # 1: The extra value added for increased productivity (969.6 billion pesos) is equivalent to 0.0169 of 2019 GDP (at constant prices).

Estimated contribution of additional GDP: 1.7% (rounded figure)

Scenario # 2: The extra value added for increased productivity (854.4 billion pesos) is equivalent to 0.0149 of 2019 GDP (at constant prices).

Estimated contribution of additional GDP: 1.5% (rounded figure)

Conclusions

The estimation exercise allows us to adopt the hypothesis that if SMEs were established in Cuba (under certain premises), it would add between 1.5% and 1.7% to the country’s GDP, a not insignificant figure in a situation like the current one.

Notes

1 ECLAC’s estimate is -3.7% and that of The Economic Intelligence Unit is -4.7%. See https://www.cepal.org/es/comunicados/pandemia-covid-19-llevara-la-mayor-contraccion-la-actividad-economica-la-historia-la

2 See, “Las estadísticas de empleo privado en Cuba: ¿una pirueta ideológica?”, blog El Estado como tal, May 6, 2019 https://elestadocomotal.com/2019/05/06/las-estadisticas-de-empleo-privado-en-cuba-una-pirueta-ideologica/

3 Considering that the “review” of the employment data carried out in the Statistical Yearbook of Cuba 2017 distorts the series of data related to non-self-employment private employment, total private employment and cooperative employment, the data for 2017 and 2018 were recalculated. It is considered that it is not necessary to adjust the official self-employment and total non-state employment data because they maintain their consistency in the Yearbook series.

Non- self-employment private employment was calculated assuming the total private employment figure for 2016 (1,139,200 workers), taken from the 2016 Yearbook, from which the figure for self-employed workers (540,800 workers) was subtracted. The result was a figure of 598,400 private non- self-employment workers in 2016. The same calculation was made for 2008, with a result of 460,500 workers.

The average annual growth of non-self-employment private workers in the period 2008-2016 was calculated, resulting in an average annual rate of 3.33%.

This rate is applied to the base data in 2016 (598,400) and the number of non-self-employment private workers is estimated in 2017 (618,300 workers) and in 2018 (638,900 workers).

Both figures are added to the data on self-employed workers from the 2018 Yearbook, for the years 2017 (583,200 workers) and for 2018 (580,800 workers), thus calculating the total of private workers in 2017 (1,201,500 workers) and 2018 (1,219,500 workers).

Then the cooperative employment figures are estimated, subtracting from the non-state employment figures for the years 2017 and 2018 (taken from the 2018 Yearbook) the recalculated data of total private employment for 2017 (1,201,500 workers) and 2018 (1,219,500 workers).

The recalculated figures for cooperative work are 185,800 workers in 2017 and 196,200 in 2028.

4 Nguyen Thang, Laure Pasquier-Doumer, and Xavier Oudin (editors), The Importance of Household Businesses and the Informal Sector for Inclusive Growth in Vietnam, co-published by Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences and the French National Research Institute, 2017. See Graph 5.4 Value added per year and per worker (labor productivity) by institutional sector (million VND)

5 ONEI. Statistical Yearbook of Cuba 2018.

6 Yenia Silva Correa, “La población económicamente activa en Cuba aumentó en más de 40 000 trabajadores en 2019”, Granma, January 19, 2020 http://www.granma.cu/cuba/2020-01-19/el-empleo-en-la-mira-de-todos-19-01-2020-17-01-45

7 Approximate indicator of productivity obtained by dividing the 2019 GDP estimate (at constant prices) by the total number of employees in 2019.

8 Yenia Silva Corrrea, “Nuevas normas jurídicas para el trabajo por cuenta propia”, Granma, November 5, 2019, http://www.granma.cu/cuba/2019-11-05/nuevas-normas-juridicas-para-el-trabajo-por-cuenta-propia-05-11-2019-22-11-20