There are stories that are not patented. Like this one. Guayabita del Pinar, a native drink that conquered palates in Cuba and beyond, is a living example of how myth and reality sometimes navigate the oceans of time like a message trapped in a bottle.

Due to the remoteness and imprecision of its origin — shrouded in mystery and rumors — as well as the string of declines that have sunk this local industry, this succinct biography must be crafted by blending, in balanced doses and with a challenge similar to that of those mountain chemists, drops of popular knowledge and excerpts from documentary evidence.

According to legend, the master rum makers of the country’s eastern province and even Bacardi himself, the king of rums of yesteryear, would have risen early in the tobacco plantations of Pinar del Río — without suspecting it. It wasn’t that the tobacco growers had any explicit notions of alcoholic alchemy, but rather that they were too cold when the winter air pierced their bones at dawn during the harvest.

At that hour, the blood called for fire, but the palate craved something less dry and harsh than pure sugarcane spirit. So, anonymous farmers began experimenting — it is even said that they began in the 18th century, or perhaps earlier — with formulas as diverse as the palates that tasted them, immersing plums, raisins and all kinds of medicinal vines in barrels of alcohol sprinkled with sugar.

Genaro Rivera, a native of Asturias who lived in Vueltabajo around the 19th century, is credited with throwing a handful of macerated guayabita from the pine forest — this fruit, due to its aroma and sweetness, used to attract farmers and wild boars to the grove — into a barrel of brandy seasoned with lemon peel, vanilla, mint, mignonette, and lemon balm.

As its name suggests, the guayabita resembles the common guava, except that it has an oval berry shape, little pulp and is no larger than an olive. “The guayabita is the size of a cherry, with a smell and taste like the Peruvian guava, but sweeter,” described Jacobo de la Pezuela in his Diccionario geográfico, estadístico e histórico de la isla de Cuba.

It is the fruit of the guabayito, botanically known as Psidium guayabita and belonging to the Myrtaceae family. It is a shrub endemic to the western region — although in the past it was reported in the jurisdiction of Sancti Spíritus and Isla de la Juventud — that grows wild in sandy, undulating soils under pine forests, which is why it was called guayabito de pinar (pine forest guava).

After letting his broth rest for a few weeks, Genaro Rivera gave it to relatives and friends to taste. They found it not only a novel liquid, but also exquisite. Without further ado, the Asturian set up a kiosk to sell it and earned his “perras gordas” (a nickname for the Spanish peseta at the time). However, he was far from imagining that this primitive liquor would become, with the aging of centuries, a drink of paradise: a symbol of identity, like Scotch whisky or Russian vodka.

The truth is — though it is tacit in oral and written history — the domestic concoction could have vanished like a cigar immolated under the law of a match, or remained restricted to the remotest sphere of the tobacco growers, if the genius of Lucio Garay, the Basque-born merchant to whom Genaro Rivera sold his “secret formula” for a gold doubloon, had not come into play.

A nail in the shoe

Lucio Garay would give that artisanal elixir an industrial label, improve its quality with constant additions and refinements, and catapult it from a tavern and foreign drink to urban consumption; in addition to establishing its notoriety in the social imagination as a folkloric drink of Pinar del Río cuisine, a restorative drink and a favorite bottle for celebrations.

Born in 1871 in the coastal town of Bakio, about ten kilometers from Bilbao, Lucio Garay Zabala grew up witnessing the ancient ceremony of macerating grapes to prepare the famous txakoli (or chacolí, a fruity, slightly sparkling white wine still produced in the Basque Country). Like many of his generation, the young villager set out to travel to the island of Cuba with the dream of making a quick fortune, specifically in the liquor business.

Flirting with his destiny, on some date no one has been able to pinpoint — between 1885 and 1891 — Lucio embarked with his older brother Fulgencio for Havana. A laconic reference in the Diario de la Marina of March 15, 1892, places them there, citing them as partners in Costals, Garay y Cía., a liquor depot located at 33 Mercaderes Street. In a short time, the emerging business launched the El Portador anise brand and the El Globo and La Africana cognacs, but Lucio had his own plans in mind.

Probably looking for a new beginning or to exploit other market niches, the young man from Biscay went to Pinar del Río, where he first became known for his love of opera, his eccentric participation in arm wrestling competitions where he flexed his muscles, and as a proud enlistee in the Volunteer Corps. However, according to the Diario itself, he was discharged from the paramilitary organization in May 1895, for no known reason.

His latent passion was winemaking. Having understood the deep-rooted customs of the Vueltabajo tobacco growers and putting his business acumen to the test, Lucio Garay sensed the promising potential of the well-known drink made from the guayabita fruit and invested heavily in the venture.

Nor can it be overlooked that, over the years, he diversified his capital as a shareholder or owner of urban properties, warehouses, small shops, the Charco del Negrito tobacco plantation, the La Occidental copper mine in Mantua, the Hispano-Cubano Sugar Company and the Vueltabajo Cigarette Company.

Physically strong and with a solid reputation, Lucio Garay was inspecting the work in his factory when an old nail accidentally pierced the sole of his shoe. Lurking beneath his skin, the rust spread through his bloodstream, causing a septicemia that doctors certified as encephalitis. On April 15, 1927, the entrepreneur died at the age of 56.

Casa Garay

Given the paucity of historical documentation and the absence of an official patent registration, 1892 has been chosen as the founding date of the Guayabita del Pinar brand. This adoption was based primarily on the “1892-1931” sign that still remains on the factory facade, and on secondary sources that confirm that, by that time, Casa Garay bottles were already appearing in grocery stores and display cases.

Naturally, the first years of the fledgling company were a testing period with many ups and downs. The 1995 insurrection, which spread to Pinar del Río, undermined Garay’s plans, as the fields where the guayabita was harvested largely fell under Mambí control.

The end of the war brought new surprises: in retaliation for having been a prominent contributor to the Spanish city council and a defender of the Crown’s interests, his establishment was looted, with the resulting destruction of property and documents.

However, an enterprising and tenacious man, Lucio Garay understood that the ups and downs were temporary and that all would return to normal once the storm had cleared. That’s why he decided to stay in Cuba when many of his fellow countrymen returned to Spain.

With the idea of reboosting the business, he partnered with Salvador Baduel and Juan Bautista Aguirre — with whom he had already founded a soda establishment at 68 Maceo Street — to establish, on April 6, 1899, Casa Garay y Compañía, a beverage factory located in his own residence at 104 Martí Street. A few months later, in October, he married María Regla Mazón Guzmán, a native of Pinar del Río, a union that produced five children.

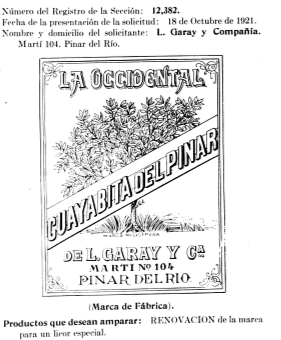

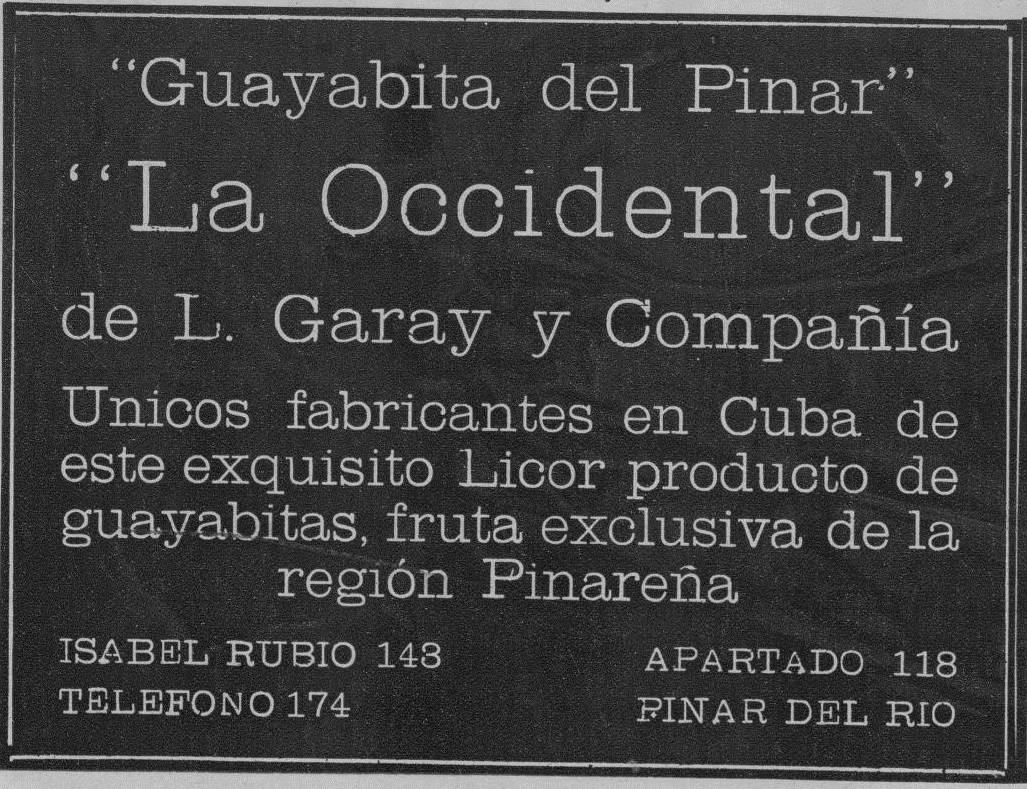

The trips back and forth to the notary to sign agreements and renew the brand’s registration followed in line with the financial ups and downs and the development dynamics of the consortium. After the previous company was dissolved, on March 3, 1904, Lucio Garay registered the La Occidental brand in the Trademark and Patent Book. This brand was dedicated to the production of medicinal waters, soft drinks and liqueurs, which would later become the parent company of Guayabita del Pinar. As sole proprietor, two years later — in October 1906 — he obtained the license to bottle and market it under the “special liqueur” label.

Harmless and treacherous?

Guayabita del Pinar was produced in three varieties: one dry like rum, another sweet like liqueur, and one as a creme. As a distinctive feature, each bottle contains at least a couple of small fruits inside. The Guayabita gained popularity for its magnificent therapeutic properties as a tonic, diuretic and digestive; it was even claimed to be useful for healing and as a preventative against mosquito bites.

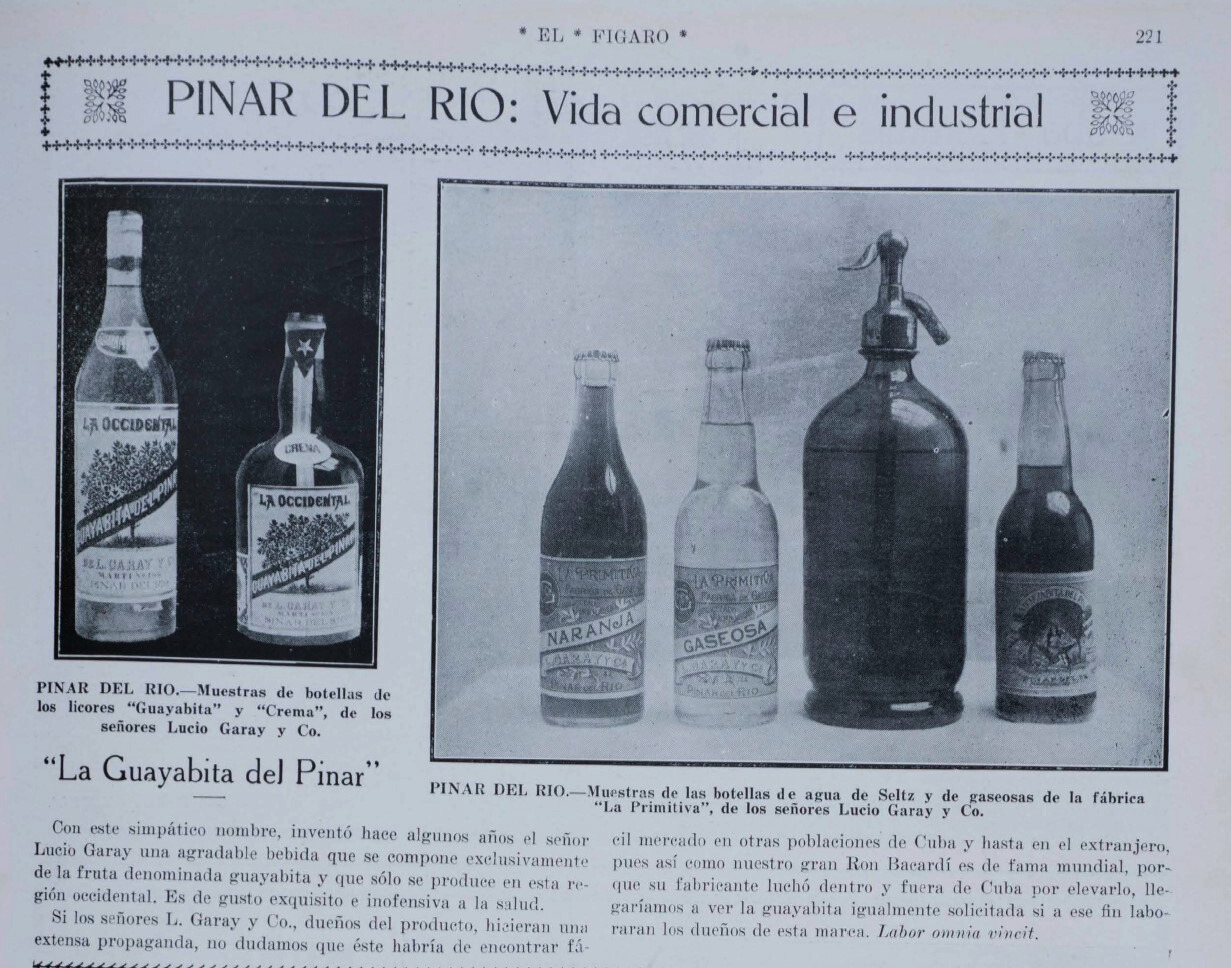

“It is of exquisite taste and harmless to your health,” El Fígaro agreed in a promotional text published in February 1918. But don’t let anyone fall into that trap. The reality is that, with over 40 proof, the so-called wine was tremendous, “somewhat treacherous,” and like other challenging and legalistic rums, it could lead to episodes of drunkenness, get the most “even-tempered” of drinkers into trouble with discord and quarrels, or, for many, even worse: end up getting into trouble with the wife.

The manufacturing process was carried out manually. The liquid was taken from the barrels to the bottling vats and, from there, it was transferred to the bottles, without the intervention of mechanized devices. Although the payroll did not exceed twenty employees, the industry soon stabilized its production line at over 2,500 bottles per month. Wines were also produced — the base wine was converted into muscatel, absinthe, sweet wine and quinine — anise, cognac, vinegar, soft drinks and perfumes.

For example, in its November 1912 edition, the Boletín Oficial de Marcas y Patentes of the Secretariat of Agriculture, Commerce and Labor detailed the soft drink’s stamp this way:

“The brand consists of a semi-oval formed at the top by an orle-shaped ribbon with the text ‘La Guayabita del Pinar’ in the center; below this and in the center are two guava trees, from which hangs a hammock in which an Indian woman reclined, holding a cup in her left hand. From left to right, the text reads ‘Delicious soft drink made with Guayabita del Pinar,’ followed by ‘Prepared exclusively by L. Garay y Ca.’ The word ‘Pinar del Río’ closes the semi-oval horizontally, beneath which is a print shop mustache type in the same font as the brand’s letters.”

The quality of Guayabita del Pinar, the flagship drink of Casa Garay, began to gain prestige and demand both inside and outside of Cuba. In 1911, the dry variety won the Grand Prize at the National Exhibition of Cuban Liqueurs held in Havana. But its consecration would come with third place at the Rome International Fair in 1924, and the gold medal won at the Plovdiv International Fair, Bulgaria, in 1988.

Cork stopper

The secrets of so many successes ended up slipping away through the labyrinths of yesteryear. After the death of the founding father, his son Lucio, with a more aggressive spirit, remodeled and expanded the factory to the maximum potential. The guayabita tied the industry to the forest. Beginning in 1959, or rather, since its nationalization, for Guayabita del Pinar began a new era, in which state control over production and exports established a series of mechanisms that would seal its fate.

For the Garay family, this felt like hitting a cork with a sledgehammer. While the triumphant motto was to oversee every step of the artisanal process, remaining faithful to its origins and striving to meet the demands of the beverage both at home and abroad, it is well known that disappointments and conflicts between rhetoric and action eventually surfaced. Of course, there will be no shortage of counterclaims that the industry declined due to the policy of economic subservience imposed by the United States.

The truth is that, for a long time, Guayabita del Pinar fermented in the barrels of oblivion, until the 1980s, when an attempt was made to revive its former vigor: agricultural studies were conducted and a program was launched to plant 50,000 guayabita plants across 20 hectares distributed across the municipalities of Guane, Viñales, La Palma, San Juan and Los Palacios. This somewhat revalued the small industry, and the age-old pocket-sized potion of the tobacco growers reached the throats of Europe. To give you an idea: in 1988, the Pinar del Río entity had contracts with Poland and Spain. That year, 10,000 cases were exported, and by 1989, the plan had increased to 20,500.

At that time, the hit parade in Cuba was: “If there’s no beer, let’s drink…Guayabita del Pinar.” A guaracha message from the Original de Manzanillo, in the spirit-filled voice of Cándido Fabré, reaffirming the idea of growing “alcoholically” in the face of difficulties. The main, and revolutionary, goal was to propose a solution to the problem of not having Hatuey beer during Carnival.

Until the collapse of national tourism, a few years ago, hundreds of tourists in the city of Pinar del Río would visit the old Casa Garay facilities daily, where they were astonished to see artisanal methods and equipment more than eighty years old in action. They would then move on to an adjacent tavern where they could placidly confirm that each sip of that unique liqueur was equivalent to tasting a forbidden fruit in a tropical paradise.

The shortage of raw materials and the absence of a saving recipe have led the Guayabita del Pinar to fall into repeated “slumps.” Let’s hope we can make a toast to it and not mourn the extinction of this intangible industrial heritage of the country.