Almost 50 years old and having completed a law degree in Cuba, Alicia is working on the construction of a 30-story building in the north of Moscow. She is part of a group of 25 Cubans (7 men and 18 women) who have been working there for about a month, doing the hardest tasks.

Without a contract, stability or protection, their only benefit is the payment of 1,800 rubles (about 20 dollars) every day after more than 10 hours of intense work, if the bosses consider that they have done it well and, of course, if they are not arrested by the police first.

This is what happened a few days ago. “They arrived suddenly, around 12:30, dressed in civilian clothes. We were cleaning windows at the time; others were knocking down the ceilings or scraping paint,” says Alicia.

“They went straight up to the 25th floor, which is where they caught 7 of the men. They warned the rest of us and we ran downstairs and hid outside, in a small room where we barely fit, trembling with fear. We did not know what was going to happen to our companions. They were not mistreated but they were taken into custody. The rest of us were hidden for 5 hours. When they told us that they had left, we were able to get out,” she recalls after the scare.

“It was a terrible day; we were all very nervous. One of the women who was with me has her child here and she pays for his care so she can go to work. That woman’s heart was in her mouth because if they arrest you they can leave you in jail or deport you,” Alicia explains.

“The men told us later that they sat them on the floor, and at around 3.30 pm they forced them to pretend they were working, especially the women, to take photos of them. That is already irrefutable proof to be deported, but those photos were under duress. They didn’t let them use their phones either. They couldn’t do otherwise; before they had beaten a Tajik who refused. They are very decent men, who are not used to that kind of mistreatment, and they did what the police told them to do.”

“It was one of the saddest days of my life in this country,” says this woman who has become something of a mother to her younger peers. “I kept an eye on my boys until they were released late at night, thanks to the Russian head of the work site, who was good and paid to have them released.”

Detained in uncertainty

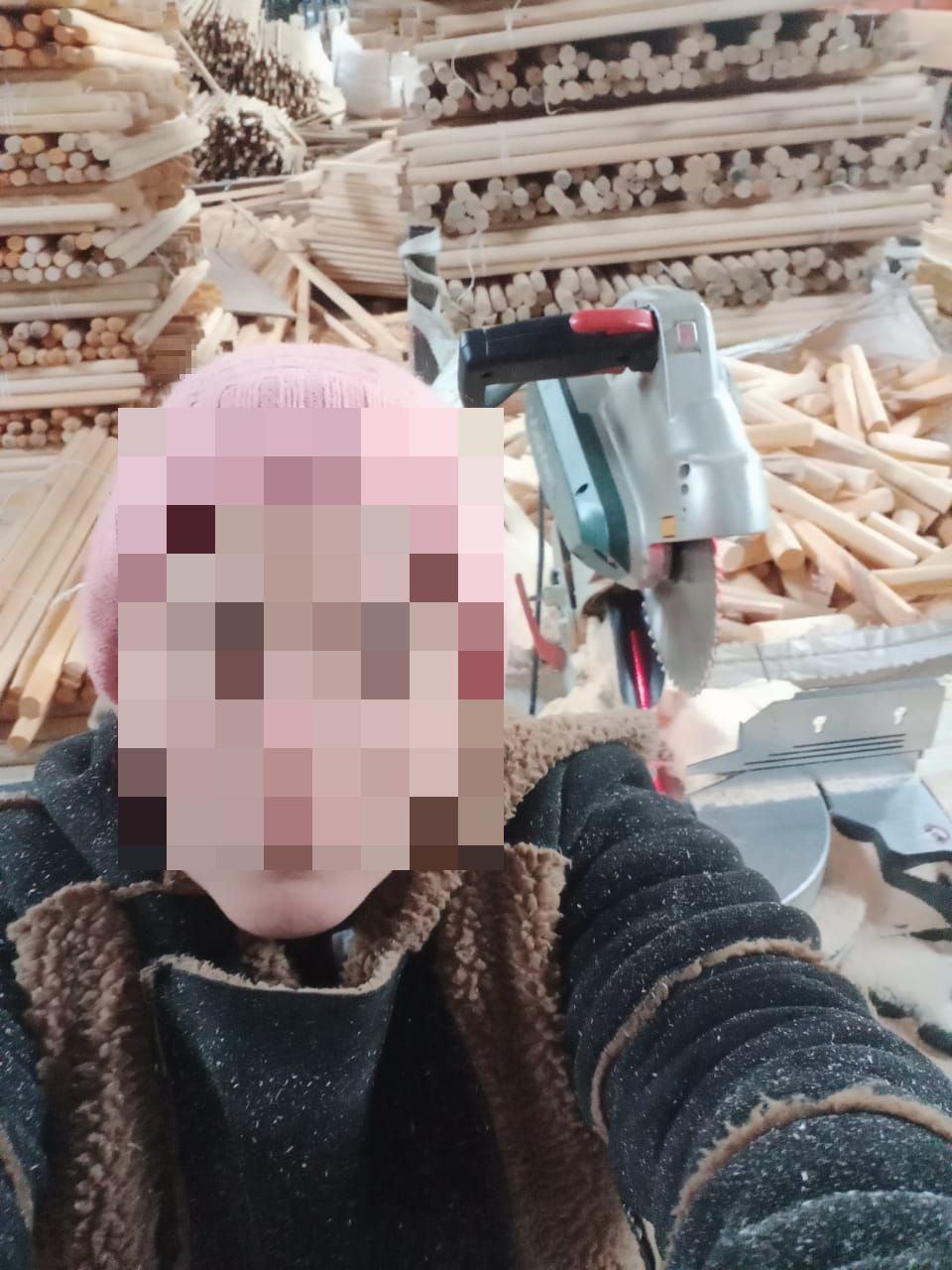

Ileana was not so lucky. She, her husband and a friend were detained at the sawmill where they worked, on the outskirts of a small town 300 km from Moscow, and they went directly to a temporary detention center for foreigners, where they have been for almost a month.

“They tried us and told us that we were going to be deported and that if we got the money for the ticket it would be quick. But we already have it and nothing. The Cuban embassy tells us that we still do not appear on the deportation lists, that they have not been notified that we are in jail. We gave them the data and they called, but we have not heard anything else,” she explains from there.

The conditions of the place are acceptable, but “there no one can eat the food,” she says and sends a photo of a serving of buckwheat, a cereal with a peculiar taste Cubans are not used to. But what is worst is the isolation. “They put me alone in a cubicle, separated from my husband and his friend. Loneliness is terrible. I only see other people when they take me out to the yard for a few minutes.”

Amid uncertainty about how and when their case will be resolved, they have been offered a “solution” several times.

“My husband and the other guy have been offered to enlist in the army to go to war, they have been told that they would give them papers and money; although not me, because we are not legally married. But we don’t want that. I have a daughter practically alone in Cuba, a minor. We had been here for almost two years now, but all I want now is to return.”

Ileana, which is not her real name, ends up asking me not to publish data or images of her that allow her to be identified. “My husband is afraid that they will retaliate. They broke another prisoner’s phone for asking for help.”

Part of a bigger problem

These are not isolated events, nor are Cubans a specific target. The operations are directed in the first place against the hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the Central Asian countries that made up the territory of the former Soviet Union and who have historically entered Russia and formed communities of millions, many of them also illegally or without the required permits.

Last week, in a raid on the Moscow warehouses of a supermarket chain and the Ozon online store, one of the largest in Russia, 57 migrants working illegally were arrested. This was reported to the Tass news agency by the head of the information and public relations department of the Main Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in Moscow, Vladimir Vasenin.

The Nikulinsky district court later found the migrants guilty of a crime. They were fined, and 44 of the offenders will be expelled from Russia with a consequent ban on entering the country for five years.

Employers who irregularly hire migrants can also be held accountable under Article 18.15 of the Code of Administrative Offenses of the Russian Federation (“Offences when attracting foreign citizens to work activity”). Violators face administrative fines ranging from 400,000 to 1 million rubles (approximately 4,000 to 10,000 euros).

Many of the thousands of Cubans who are in the country irregularly find occasional work — and generally precarious — in warehouses or cleaning jobs in supermarkets or other positions that do not require high preparation or special command of the language. Those known as “magazines” (from the Russian word for store, “magazin”) are a focus of attraction for the authorities, who are aware of these practices.

“A friend in my rent was caught working in a magazine and with her everyone around. Although they were not deported at the moment, they placed a deportation order on them and left them in prison for two days,” says a Cuban in a WhatsApp group.

“The demand for immigrants is mainly focused on low-skilled labor, in the service sector, as well as skilled labor in industry and construction,” said Deputy Minister of Labor and Social Protection Elena Mujtiyarova during the recent International Economic Forum in Saint Petersburg.

“Since foreign workers do not compete with Russian citizens and allow us to solve tasks necessary for the economy, we understand that they would be attracted to these areas,” she said.

The deputy minister added that the number of migrants is expected to increase by 15% this year, and that it is necessary to develop adequate and regular attraction mechanisms.

Meanwhile, migrants are exposed to corruption, scams, police excesses, persecution, violation of rights, and even pressure to join the army. However, many continue to see Russia as an opportunity to get what they do not have in their countries and get ahead.

Cubans are no exception, although in most cases they remain illegal, sometimes for years, literally living from day to day. With the sword of deportation permanently hanging over their heads.

Compared to those from the island, migrants from the former Soviet republics have enormous advantages, since they generally know the language and there are ways to regularize them. In this sense, Cubans are playing with the odds of losing, due to the impossibility of obtaining the necessary permits to work, or residency; in addition to the cultural and language gap.

Even so, there are thousands who get up looking for how to earn a roof over their heads and daily bread, in addition to often supporting their loved at home.

“We are all mothers and fathers between the ages of 20 and 50. In Cuba almost all of us were professionals; among us there are doctors, nurses, teachers…. But we have children to support, and that is why we need to work. We can’t get tired,” explains Alicia. “We are afraid, but the need to survive here is greater, to pay the rent, to eat and to send money to the family in Cuba.”