Juan Pablo Cabrera wants to get high for the simple reason that it’s Friday. For more or less four years he has had this habit that, for him, can in no way be understood as a vice. “It’s a need, just the need to forget about myself for a while,” he says.

Juan Pablo, 28, leaves work at four in the afternoon from a renowned bank located in downtown Medellin, grabs the subway at Parque Berrío and gets off at Poblado station, walks nine blocks, buys an energy drink to mitigate the heat, gets to a building, kindly greets the doorman, presses the elevator button, goes to the seventh floor, enters his apartment, opens his backpack, takes off his shirt with the bank logo and puts on a muscular Puma brand, sits in a beanbag, grabs his XR iPhone and on WhatsApp searches for Rami. Once the contact is found, he says hello, waits for an answer and, after exchanging some words, Juan Pablo asks for a gram of Tusi (synthetic drug), they agree on the price (40 USD) and the delivery time (7 pm).

Almost half an hour after the agreed time the iPhone rings as if it were a fine bell. Rami and the Tusi have arrived. Juan Pablo calls the doorman and asks him to let his friend in. The doorbell of the apartment is dry and vibrant. Through the door enters a character that looks like he’s been taken from a hip-hop video: Jordan brand cap, white T-shirt two sizes larger than required with the symbol of the New York Yankees at heart level, bulky black pants and white Nike sneakers. He wears a scrupulous golden chain around his neck with a pendant that bears the letter R with diamonds around it.

Rami asks about me. Juan Pablo introduces me and tells him that everything is fine. “Nice to meet you, partner, I’m Rami and I’m at your service for whatever you need,” he says, with a particular Caribbean accent, while he shows me his right fist so that I clash it with mine as a sign of friendship.

Without asking, Juan Pablo fills three glasses with ice water and sits down to talk. Rami drinks the water in a single gulp, talks about the weather, about a couple of parties that are trending in the city, about a girl who drives him crazy and hurries to make the transaction with the excuse of not being able to stay long. On the table he puts a transparent bag that reveals a delicate pink powder. Juan Pablo takes some bills out of his wallet and, thanking him, hands them to him. Rami doesn’t count the money. I ask him what else he sells and he replies that whatever I need, that the only thing he doesn’t sell is marijuana, but from there on he has more than 95% pure cocaine, varieties of parakeet (lowered cocaine), pepas (ecstasy), acids (LSD), popper and heroin.

Rami’s phone rings. Juan Pablo goes into the bathroom with the Tusi. Rami complains because someone canceled an order and says he has nothing to do until 10 tonight. Juan Pablo comes out with his eyes a little brighter than before and a slight smile painted on his face. “Well, then put on something Rami, that song you showed me the other day, the therapy I think,” says the host. Rami synchronizes his phone with a soccer ball-shaped speaker, turns up the volume and the melody starts frolicking. Juan Pablo asks me to listen to the lyrics carefully:

Personal therapy from the free yah cave / if you want to rest very peacefully on your bed, / correct your faults if you believe you’ve done something bad, / fight for your cause, keep the right course, / never repress what’s inside you, / follow your path, even if it’s narrow, well satisfied, / to be alive, have family, food and shelter, / it isn’t the same to get experience as it is to make a profit, / in small pieces you can end up banished.

These Cubans are geniuses, says Juan Pablo. No, the genius is the author who writes these lyrics with cachet and without any crap, says Rami. Who’s the author? I ask. Silvito the free, says Rami. The son of Silvio Rodríguez, adds Juan Pablo.

***

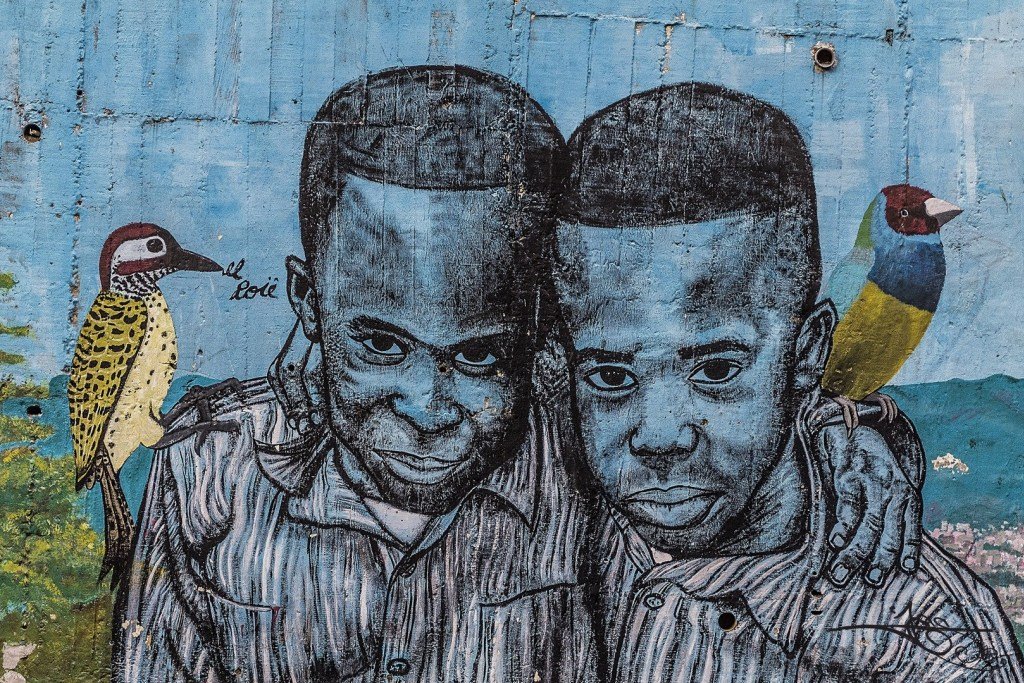

Medellin is Colombia’s second city. It is estimated that, of its two and a half million inhabitants, some 400,000 consume some illicit substance, either to forget their problems or recreationally. Having access to a dealer in Medellin is more than easy, the only thing that the potential consumer needs is a phone number and the name of a person the dealer recognizes―to be on the safe side―and who works as a contact. On the other hand, if the interest is to buy directly, it is enough to approach the journalists’ park, the Antioquia neighborhood or the San Javier neighborhood, located in the famous Comuna 13, in addition to the simple approach to an endless amount of mobile sellers generally located in party areas such as Parque Lleras, 33 or 70 streets.

However, according to law 30 of 1986, the penalties for trafficking or illegal transport of drugs in Colombia range from between 1 and 30 years, always according to the amount seized. For example, the minimum dose is not penalized. This means that any user can carry up to 1 gram of cocaine or 20 of marijuana without being stopped, but if a user is found with a maximum of 100 grams of cocaine or up to 1,000 grams of marijuana the penalty varies between 1 and 3 years in jail or a fine of up to the 100 monthly minimum wages in force (the current minimum wage in Colombia is 245 USD). If the volume amounts to these values provided by the same Colombian State, depending on the case, the penalty could be up to 30 years.

In Colombia, drug trafficking is considered a serious crime, even more serious than rape. For the first, as stated, the maximum penalty is 30 years in jail, while for the second, the maximum penalty is 20.

***

Rami is not really Rami’s name. The one who was called Rami (for Ramiro) was his father who died in 2012, when he was 17 years old. Rami’s real name is Carlos and, as a boy, the neighbors of Cerro, in Havana, called him Carli, as a way to identify him from his father.

Carli’s mother died a few hours after childbirth. She died from an unstoppable hemorrhage. About her, Carli only knew that her name was Margarita Sánchez Torres, that she was blonde and a great salsa dancer, from a Colombian city called Ibagué and that she had arrived in Cuba at the end of the 1980s with the firm conviction of personally living the socialist experience.

Carli inherited his mother’s nationality and his father’s taste for music. Since his death he never again had contact with his Cuban family, for a fundamental reason: they’re from Guantánamo, which always meant a rigorous distance. What hurt Carli most after his father’s death was the fact that he had spent the last years of his life, before falling ill with a sudden and devastating cancer, saving with the intention, or rather the dream, that both of them leave Cuba to settle in Colombia.

After three years of loneliness, street, alcohol and problems with the authorities, in 2015 Carli decides to sell everything and take on the challenge his father had for both of them. At that time, the 20-year-old was a prominent rapper who animated the underground scene of Havana with a furious freestyle that mixed poetry and existentialism. His pseudonym was Ramix and he never got to record something because, according to him, “in the rap universe, talent almost never matters, and so, either you have to have money and a pretty face or you have to be an acclaimed bad artist, and I don’t have one or the other.”

In November 2015 he landed in Bogotá, spent some nights at a hostel in La Candelaria neighborhood and, after being fed up with the cold, he decided to go to his mother’s city with two backpacks with his belongings and a phone number that his father hoped to dial the day they arrived in Ibagué.

Once there, Carli found a hotel and went out to call. When they answered, he said: Yes, good afternoon, my name is Carlos and I am Margarita Sánchez Torres’ son. Do you know who she was? A woman’s voice, on the other side of the line, reacted immediately: No, you’ve got the wrong number. Carli hung up and called again and the same voice said: I don’t know any Margarita or anyone who has lived in this house before, what I can do is give you the number of the real estate agency that sold me the house. Carli wrote it down, and then discovered that the real estate agency no longer existed. He spent a bit over a month in Ibagué looking everywhere, talking with each person and institution in the hope of finding some clue or sign that would lead him to some member of his mother’s family, but it was all in vain. He didn’t find anyone.

One morning, while Carli was having the breakfast offered by the hotel, he saw a news on television that called Medellin the world headquarters of reggaeton, thanks to the great proliferation of artists of international stature that the city had for several years. When it finished, Carli went up to the room and without thinking twice began to redo the bags and find out how far Medellin was. Eight hours, by land, separated him from that city that in his previous imagination was a battlefield, a no man’s land ruled by drug trafficking bombings and guerrillas.

At night, while traveling, confused, unable to sleep, he made a truly transcendental decision: to start presenting himself as Rami, because if he had not been able to trace anything about his mother, it was as if she had never existed, while his father had always been there, by his side and, even dead, he was never going to stop being there.

Rami felt good since he set foot in Medellin. He stayed at a hotel near the Atanasio Girardot Stadium and, on the famous 70th Avenue, quickly got a job at a disco. After a year he was already consolidated as head of the bar. One night, a regular customer told him that he and his partner were needing young people who were eager to progress to work making home deliveries “of various things” with a weekly salary that was going around in Rami’s head: four times more than what he earned at the disco and working half the hours. Rami accepted that offer and quit the bar without knowing what the home deliveries were.

When he finally found out what the job was, he was not scandalized either. His immediate conclusion was: I can no longer go back, I just have to be discreet. At first it was weird, it made him feel like a drug dealer, but he quickly realized that he wasn’t, that he only distributed some products that, moreover, were not to his liking.

Rami has been working as a dealer for two years. He has never had a single problem with anyone and buyers, according to him, want it a lot. He says, for example, that last December some clients gave him bottles of whiskey and clothing vouchers. He doesn’t think too much about whether his activity is moral. He says that everyone is free and autonomous to do what they want. He lives alone, in a small apartment a few blocks away from Parque Lleras, the party nerve center in Medellin. He fears neither the police nor prison and every time he runs some kind of risk he repeats to himself, like a mantra: I can no longer go back, I just have to be discreet.

For now, Rami only thinks about retiring from the business once he has what he needs to set up a recording studio specialized in rap. He states that he has never been interested in drugs, that they seem stupid to him, and that this may be the key to his job success. He doesn’t miss anything about Cuba and claims to be at ease with the life he leads, and his only weakness, vice, if you like, is the excessive taste for new clothes.

***

Juan Pablo and I listen carefully to Rami’s story. Until it’s 10 o’clock and he has to leave. We have gone through a whole playlist of Silvito the free and, every so often, while Rami spoke, he interrupted to babble fragments of songs that strangely functioned to complement his experiences. Rami leaves and Juan Pablo returns to “Terapia,” the song with which it all began, while he goes to the bedroom, to change to go out to enjoy the night and the Tusi, that magical dust that makes him forget for a while.