Even under an indescribable sun that makes the asphalt sweat, a disconcerting coldness lingers in San Juan Hill. Silence and solitude have opened their umbrellas there. There are times when not a soul goees by. Without tourists, regular visitors or many passersby, the memorial park conveys a certain hieratic and monorhythmic morass of a cemetery. That biting helplessness that oblivion tends to polish with its subtle emery fingers.

Many Julys ago, in 1898, this hill located on the outskirts of Santiago de Cuba was the scene of the bloodiest and most decisive battle of the Spanish-Cuban-American War, in which, amid heroic breaths and flesh-eating bayonets, one empire was broken and another was raised: the eagle intervened to kill a sparrow. That pivotal and complex conflict not only placed the provincial jurisdiction at the center of global attention, but marked a turning point. A new geopolitics was born there.

Today, however, the enormous historical and symbolic heritage of San Juan Hill suffers the same fate as a treasure chest that ends up broken and confined to the shadows of an attic.

Born and raised in a nearby neighborhood, I had this historic site in my sights for almost thirty years. I walked through it dozens of times. The first was with my father, who planted the seed of my obsession for monuments and legends from an early age; later, on school-led excursions or personal trips. In fact, it was my favorite route to reach the amusement park through the entrance where the mammoth Ferris wheel rises.

Perched 90 meters above sea level, the park is a natural lookout point. The panoramic view and the breeze that constantly caresses the mysterious valley are marvelous. In the distance, it reflects the suspended, picturesque city, offering a kaleidoscope of perspectives like a Botalín painting.

And I went there recently, to assuage nostalgia and curiosity in equal measure. How can you say no, Sabina? You have to return to where you were happy. Even if it hurts like the truth, every return is as moving as poetry.

San Juan is a gateway to a historical — and controversial — period of cosmopolitan significance, a way to connect with our ancestors, to walk where they once walked; the opportunity to feel a tradition that is often blurred by the subculture and ignorance that kills people, as Martí once said.

Of war and peace

As so often, San Juan greets me with the confusing corporeality of a glass. Half empty or half full? The same cannons and the same trees, all in the exact same position as the last time. Nothing has changed. Or has it? In a city that, through its bumpy and turbulent streets, moves quickly and steadily toward disaster, the memorial park astonishes passersby with the cleanliness of its green areas and the preservation of its relics.

Between those war artifacts that very few stop to contemplate and the compassionate shelter of the trees, San Juan offers romantic hospitality. Some couples in love know this well. I don’t know how to explain it, but even in full sunlight — a powerful enemy of ghosts and shadows — I am always overcome by a piercing affliction in that deserted park. And in the mad mill of my nonsense, I can’t escape the suspicion that it’s caused by the lost souls who wander there.

Where peace now reigns, the tambourines of war once resounded. There are echoes that never die in that mystical, centuries-old atmosphere that captivated me since childhood.

At dawn on July 1, 1898, the allied forces — the United States Army, commanded by the obese Shafter, and the Mambí Army, led by Lieutenant General Calixto García — opened fire with the aim of forcing two strategic positions in the defensive system around the besieged fortress: El Viso and San Juan. Quartered in the El Viso fort, adjacent to the town of El Caney, 550 Spanish soldiers resisted the onslaught of 8,000 men and four cannons for ten hours.

Simultaneously, closing a sort of pincer movement, the divisions of Generals Wheeler and Kent, supported from the El Pozo estate by Captain Grimes’ artillery battery and spearheaded by Summer’s brigade, directed a series of combined attacks to occupy the Spanish outposts protecting the San Juan plateau. The fighting was intense and fierce, almost hand-to-hand, with fixed bayonets, cavalry charges, shrapnel and clouds of smoke. In the best style of a Hollywood film, the charge to the summit by the “rough riders” of Leonard Wood and Teddy Roosevelt (later president of the United States) would be glorified, although, ironically, the famous rough riders fought on foot due to a lack of horses.

At San Juan, the Americans presented themselves with an overwhelming superiority of 8,000 men — at 10 to 1 — with twelve rapid-fire Hotchkiss cannons and four Gatling machineguns, but with a flawed assault strategy in which courage and tenacity prevailed over tactical order. “The Americans, it must be agreed, fought that day with truly admirable courage and determination,” noted Navy Lieutenant José Muller y Tejeiro in his book Combates y capitulación de Santiago de Cuba.

However, the reckless attack proved catastrophic: the trail of casualties totaled 1,240, including 144 dead. As if that weren’t enough, they were immediately embarrassed when they were forced to request assistance from Colonel Carlos González Clavel’s Mambi detachment for the final assault. On the battlefield itself, the American command extended its recognition to their Cuban partners — who, incidentally, suffered 150 casualties — for their valuable performance, even though days later they would not be allowed to enter Santiago or participate in the victory ceremony.

Barracked in a fortified house on the summit, some 350 Spaniards resisted with Spartan grit until, around three in the afternoon, when ammunition was exhausted and the garrison hopelessly destroyed, it became impossible to hold that last stronghold.

To give you an idea: two companies of the Talavera Peninsular Battalion, which entered the action with 150 men respectively, were left with 30 and the other with 50, according to Spanish commander and chronicler of the event, Severo Gómez Núñez. In total, they recorded 267 casualties, including several commanders and officers among the dead and wounded, such as General Linares, military governor of the fortress, Colonels Baquero and Díaz Ordóñez, and Navy Captain Joaquín Bustamante, inventor of the torpedo system of the same name.

Two weeks later, on the afternoon of July 16, the high commands of Spain and the United States met under a sturdy ceiba tree at the foot of the hill to sign the surrender. These land battles and the sinking of Cervera’s fleet three days later marked the beginning of the end of four centuries of Spanish rule in Cuba.

Monuments that speak

In steel, marble and bronze, San Juan manages to encapsulate the battle that made it famous and pay fervent tribute to its heroes. Among the most attractive elements are the Monument to the American Soldier, the Victorious Mambí and the column with a relief of the Spanish Soldier. Most of the statues and ornaments that make up the sculptural complex were not erected immediately after the war, but later.

Among the first to appreciate the site’s historical value was Mayor Emilio Bacardí, who in December 1898 ordered a wire fence with a handmade explanatory sign to be temporarily placed around the so-called Tree of Capitulation or Peace, until a more worthy tribute could be made.

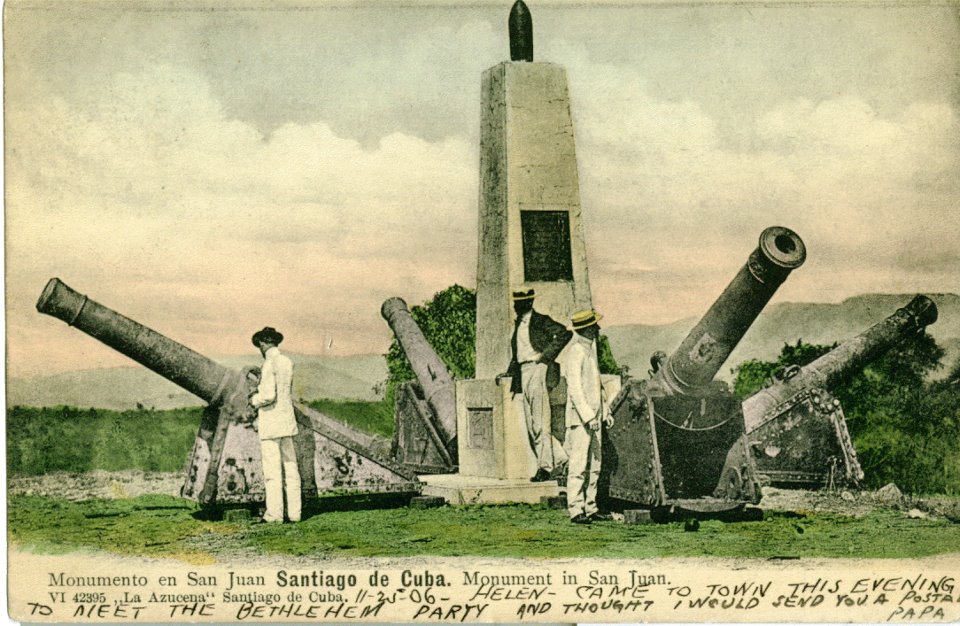

Starting in 1902, the number of hikers on the grounds of San Juan grew, especially the marines who landed in Santiago, and tourists who also began arriving from the United States, eager to see the scene where their families and compatriots had fallen or achieved glory. But the uncontrolled wave of public activity brought looting and desecration. Many wanted to take the remains of the war material that had been scattered across the former battlefield as trophies. A zealous guardian of local relics, Bacardí understood that the establishment of the historic site was imminent. Thus, in February 1906, he led the inauguration of the first stone obelisk surrounded by four cannons. It still stands, however, without its artillery pieces, as they were relocated.

Over the following decades, new components would be added, but it wasn’t until 1928 that the enthusiasm and dedication of Colonel José González Valdés gave the memorial park its most brilliant and definitive appearance. As such, it was inaugurated on a Sunday, July 1 of that year, with speeches, a marching band and a parade before a large crowd. It was an achievement that “this rugged place was stripped of its weeds and intricate thickets, turning it into a paradise,” reported Revista de Oriente at the time.

The unfathomable list of prominent figures who have passed through San Juan includes Miss Alice Roosevelt, the writer Eva Canel, the Russian painter Vasili Vereshchagin, the educator María Luisa Dolz, Pablo de la Torriente Brau, Juan Bosch and Nicolás Guillén. More recently, the Beatle Paul McCartney visited it in 2000, and the Spanish monarchs, Juan Carlos and Letizia, in 2019.

The hill is populated by cannons. They are the most resounding allegory. Through their silent mouths, they project warnings about the consequences of taking up war as a pastime. The most impressive and resplendent, a 16-centimeter González Hontoria, which, when the naval blockade was lifted from the Reina Mercedes and placed in a coastal defense position, welcomes us to the park.

Not far away, a bust of Colonel González Valdés, who directed the park’s reconstruction, watches the horizon with a stern gaze. Everything is a direct vestige of that battle that redefined Cuba’s fate, as foreign interests overrode local aspirations.

Heritage without a people?

The fake fort — because it actually never existed — is one of San Juan’s most famous postcards. For a long time, it remained open, allowing access to its upper floor, from where the quality of the view is even higher. However, it was more “exploited” as a public restroom or a “nest” for furtive lovers. Now it has a door; I suppose it’s a sort of park ranger’s office, or something similar. No one comes out to check on me or offer me a breviary. The place remains closed during the half-hour of my visit, although I can hear voices inside; they come through the loopholes.

They’re talking about the heat and politics, of dreams and tedium, the two-faced calamities that juxtapose our days. The paths of our dreams are as diaphanous, there are as many deep trenches between our ideas as those dug by the Americans and the Spanish around San Juan. To remind us of what an open wound in the earth represents, some trenches remain where hundreds of lives were buried by the stubbornness of those who commanded them. Time and again, in their bustle of greed and intrigue, humanity says goodbye.

San Juan remains an imperishable sediment; it is sacred territory. But in an increasingly disconnected and virtual world, the tangible and visceral nature of this history lies beneath a stark contrast. It seems like a place frozen in time, not only because of its mission to preserve and exhibit antiquities, but because of the curtain of indifference that envelops it. The monuments are there, standing tall in the sun and the clear air, resisting the passage of time, but the most important thing is missing: the people who receive their message.

I leave the hill with a bittersweet feeling. I think that, so focused as we are on the daily grind, we increasingly disdain the weight of history. An environment with such heritage value deserves more than this neglect. I think of those cities around the world where monuments are often sources of pride, meeting places or spaces for meditation for those who see them as an emblem of heritage and identity.

Monuments are often political tools, educational documents and sources of income based on their tourist interest. They encourage a deep understanding of how historical episodes should endure in the collective consciousness. Grappling with history isn’t just about placing anniversaries on an anachronistic mural, reading biographies or delving into dusty archives, but about understanding how the influences of the past are present in our present and shape our future.

Perhaps, at some point, this relic can be saved from its ostracism and the San Juan Tree of Peace Memorial Park transformed into what its founders envisioned: an open-air museum where history can converse with the people. The battle on San Juan Hill is not over.

Igor thanks for this ,I live in Vancouver Canada, I have been to STGo 30+ times and every time I go there I will visit San Juan hill and I agree with you 100%