Our time is a specialist in creating absences.

Ailton Krenak, Brazilian indigenous leader

Most of us have heard or treasure in our personal lineage the story of a great-grandmother or great-great-grandfather who came to Cuba to found, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, a new family history and, also, that of the people we are today. The biological synergy we are made of and all the dimensions that can be considered part of that complex universe that we call “culture” are, in large part, the result of these migrations. But we know very little, almost nothing, about the submicroscopic fraction that we Cubans inherit, at a genetic and cultural level, from those who were here before the first ships could be seen on the geographical horizon of the island.

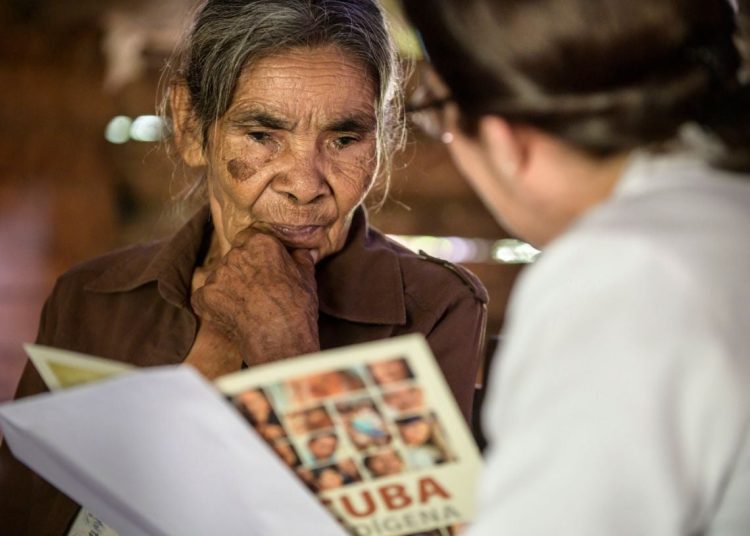

Responding to this gap in the knowledge of our ancestral history was precisely the mission of the Cuba Indígena team, a project undertaken between 2018 and 2021 by Huelva photographer Héctor Garrido, its director, Doctor Alejandro Hartmann, historian of the city of Baracoa, Julio Larramendi, photographer and visual creator, Enrique Gómez, sociologist, and Dr. Beatriz Marcheco, director of the National Medical Genetics Center of Cuba, who was in charge of carrying out genetic tests on 27 families with Amerindian ancestry in the eastern region of Cuba.

It was precisely the contribution of this last discipline, genetics, to the study, that turned on its head everything I had learned until then about the myth of the extinction of the native populations of our island; it also made me wonder why, if the traces of the descendants of Cuban indigenous people were among us all this time, that information was not socialized or told in another way in the textbooks with which we learned History. The results of Cuba Indígena also healed how much I have regretted having to deny to those who have asked me about our origins that, in addition to Spain and Africa, something of our indigenous ancestry could also remain among us.

Motivated by all this, I went out in search of Dr. Beatriz Marcheco, who, in addition to directing the Cuban Medical Genetics Center, is a practicing doctor and specialist in clinical genetics, the discipline that is dedicated to the study of hereditary diseases within a family and those others that, not being hereditary, are caused by alterations in the DNA sequence. She has also conducted important research in the genetic field in our country, such as that which sought the genetic causes of disabilities, or the creation of the National Twin Registry, completed in 2006.

“I started studying genetics immediately after finishing medical school. Genetics is one of the sciences that is at the frontier of medical knowledge and explains many of the health phenomena that we suffer from on a daily basis, not by itself; that is, genes are also in permanent interaction with the external environment (climate, culture, social relationships, living conditions), but also the internal environment, that of our organism, such as the food we eat, body temperature, psychological or physical traumas that we suffer, etc.,” she told OnCuba.

I was fascinated that a doctor spoke of genes as a microcosm, sensitive and responsive, like any other living being that feels, suffers and responds to the stimuli of its environment. But I wanted to know more about “Cuba Indígena,” the project that took up and questioned the answers given by history to what, for me, was already a settled conversation about our origins. In long and choppy exchanges via WhatsApp, Dr. Marcheco answered each of my concerns. With fascinating didactics, she talked about mitochondrial DNA, telomeres, letter combinations that make us up, what I understood to be the fraction that my basic knowledge of biology allowed me to reach.

But, more than about biological sciences, I felt that our conversation was above all about ancestry and memory, about stubborn genes that, for more than 400 years, silently resisted, through a maternal lineage of grandmothers, mothers and daughters who did not let them perish and that today give us the excellent news that indigenous ancestry continues its journey through this island in the present.

According to Dr. Marcheco, “the majority of women who survived the near extermination of the Cuban indigenous population, in addition to accepting the pain of the loss of their communities, often had to submit to the will of the colonizing man. It was they who transferred that imprint, today indelible, of the Amerindian component in our DNA.”

Mitochondrial DNA is the part of our genetic information that only eggs are capable of transferring to the embryo, the contribution that our mothers make to the formation of a new life. “The mitochondria is an organelle that makes up the cytoplasm of cells and contains its own genetic information. In this way, those of us who dedicate ourselves to researching the genome pay special attention to mitochondrial DNA because it has a very interesting peculiarity: the mother transfers it to her sons and daughters, but, in the case of the sons, the information is not transferred back to his descendants. This happens because, as we know, a new individual is formed from the union of an egg with a sperm. Unlike the egg, which has a nucleus and cytoplasm, the sperm only has the nucleus and, as I said before, the mitochondria are present only in the cytoplasm. Therefore, since the sperm does not have cytoplasm, it does not contain mitochondrial DNA.”

In other words, researchers enrolled in “Cuba Indígena” have been able to conclude that the presence of Amerindian lineages in the Cuban genome today owes its existence to the resilience of Indo-Cuban women. A finding that does not come, however, without regretting what this perpetuation of genetic inheritance meant for them in the context of the colonial violence exerted on the native peoples of our island, in the face of which not only history but also genetics, has a lot to say today.

Point of departure

“Since 2005 we have been working at the Medical Genetics Center on the characterization of the Cuban genome, which is nothing other than distinguishing within our genetic characteristics which are those that differentiate us from other populations. Among these characteristics is that we are a mestizo population, originated by the mixture of four main ethnic groups: Europeans, Africans, Amerindians and Asians; in addition to other groups of immigrants who were arriving in Cuba, but whose imprint in our genetic information does not reach the visibility or magnitude of these four groups.

“First, in 2005 we studied a group of 600 people from Havana and Matanzas who had the peculiarity of being people 60 years old or older. Then, between 2012 and 2018 we did a more comprehensive study with the support of the ONEI Population Studies Center. We then used a sample that was representative of certain characteristics of the Cuban population and to do so we covered 137 of the 168 municipalities in the country. More than 1,000 people over 18 participated in this study because children do not participate in this type of research that does not seek to study a specific disease, because they do not have the legal capacity to give their consent. We used different types of genetic markers in this study and it resulted in a fairly deep analysis of admixture in Cubans at the genome level. All of these studies precede the Cuba Indígena Project and had already indicated the presence of Amerindian genes in an average proportion of 8% and up to 20% among the participants.

“Thus, in 2018 Héctor [Garrido] invited us to be part of the project. After having a conversation with him and knowing who was involved, as well as the scope of the project, and that we had the legal framework favoring our incorporation into it because our Center has a research project approved by the Ministry of Health which is focused on the characterization of the Cuban genome, we enrolled in this research, conceived by Héctor to address the study of the families that have inhabited the easternmost area of the country for hundreds of years and that had previously been explored in expeditions by ethnologists, anthropologists and geneticists organized by the Cuban Academy of Sciences.

“In this new stage in which we could reissue these expeditions, we would have the opportunity to use new tools at the DNA level to determine the contribution of Amerindian ancestral origins to the physical characteristics that these people present.

“In 1952, Canadian professor Rubens Gates published a scientific article in a Harvard University magazine, in which he described the physical characteristics and traits of a group of people from the eastern region of Cuba who were children at the time and, curiously, participated in our study in 2019, already elderly. Thus we were able to resume the initial clinical, physical, and anthropological information described by Gates to now complement the DNA studies.

“In the 1960s and 1970s, scientific expeditions were also carried out from the Cuban Academy of Sciences, headed by Professor Manuel Rivero de la Calle and researchers from the former socialist camp who had experience in Anthropology. All this legacy helped us to explore previous information and apprehend or take back important elements from the previous legacy to be able to explore the Amerindian component present in those individuals and families at the DNA level.”

How were the participants chosen?

The selection of the families and communities that would participate in the study was carried out in the first instance by the historian of Baracoa, Alejandro Hartmann, who knows the area very well and has been touring that region and documenting the presence of people whose physical characteristics coincide or are reminiscent of those described by the colonizers themselves and other historians at a time when the indigenous populations were numerous in Cuba. It had already been reported that the surnames Ramírez, Rojas, Rivero, among others, predominate among members of families in which Amerindian phenotypes are perceived. That was the first source of information for the selection of the sample.

We chose families that over almost two centuries had been studied by researchers who had described in detail the physical characteristics of the Amerindians of the eastern region of Cuba, we ensured that the surnames corresponded to those referred to as the most common linked to those characteristics in these investigations, and also that it was possible to study people as close as possible to the genealogical origin of those families (the oldest) and, finally, that the number of cases to study had to adjust to the resources we had.

How was the fieldwork and familiarization with the participants carried out?

The first expeditions were organized to reach some mountainous areas of Granma, Holguín, Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo, where the families and their members were located. In the first stage, we visited 27 families from these four provinces, we created their family trees, that is, we documented all the information about the current and previous generations; we went as far as the families were able to remember and give us information.

As for the fieldwork, it was done in approximately 12 or 14 days; we carried out a first expedition in which we previously prepared the dynamics with which the team was going to work, we designed an instrument to collect information on the lifestyle of the participants and the generations preceding them, diseases they suffered, lifestyles and which also included other sociological indicators. Once in the communities, we asked each participant for informed consent which, from an ethical point of view, is a necessary procedure to carry out these studies.

Each person received a detailed explanation of what the study consisted of and their participation in it, how the data will be protected, who will have access to it, etc. Each one signed the consent authorizing their participation and subsequently, the interview was applied and a unique biological sample was collected through saliva to carry out individual DNA studies. To do this we used a traditional and non-invasive collection method with a swab that is rubbed on the inner side of the cheek and thus skin cells are collected from this mucosa to extract the DNA.

In the event that the sample was not useful, we could not complete the DNA study of that person because, since they were in very remote places, we did not have the possibility of returning. We also measured people’s height and strokes and took individual photos and photos of the daily collective dynamics. This is how the team worked on the ground; we slept in the same communities to use the time we had more efficiently; traveling to the provincial capitals was not feasible due to the distance. In this way, we collected the data necessary for the research, which was not restricted to analysis later in the laboratory, but rather to the combination with other tools that we applied such as the reconstruction of family trees, family histories, etc.

After the fieldwork, we prepared the conditions for the study in the laboratory. For this, we had the support of institutions from Germany and Denmark that were co-participants in Cuba Indígena, such as the University of Aarhus in Denmark, the Copenhagen Serum Institute, and the Max Planck Institute for the study of the evolution of human beings. These organizations also collaborated with the resources we required to analyze the DNA samples.

At the same time, we made a detailed review of the scientific literature and reconstructed the work of about five or six generations of researchers who since the mid-19th century (specifically in 1847, when the Spanish naturalist Miguel Rodríguez Ferrer began to describe “remains” of indigenous groups who, due to the remoteness of their residences, had maintained a certain “purity” in their genetics) began to visit these regions, document and write about these families, their phenotypes, etc. In that literature, we located and matched information taking into account the families that were in front of us in 2019.

Did the members of the community know about their genetic history?

Yes, they know their origin and call themselves descendants of the first inhabitants of the island; it is information that has been passed from generation to generation. These people have been approached over almost two centuries by different teams of scientists who have studied the area. When we arrived in these communities, in 2019 it was not the first time that someone approached them to investigate their origins. Furthermore, they have always identified themselves as indigenous people.

What ethnic-ancestral origins predominate in the results of genetic tests?

In the case of the Cuba Indígena study, it was interesting for us to see how, although we expected that the mitochondrial DNA of the participants in the study would lead us to one or, at most, two groups from a given region of the Americas that were able to settle on our island hundreds of years ago, there were more. For example, this was the case with the people of the Bella Pluma community, located on the southeast coast, in the Guamá municipality, Santiago de Cuba.

The mitochondrial DNA of these people suggests that they descend from a group that has been frequently reported in studies with inhabitants of the Caribbean and Central American islands, specifically in Amerindian groups from Panama and the Dominican Republic. Therefore, the mitochondrial DNA of the inhabitants of Bella Pluma fundamentally comes from this region. The mitochondrial DNA of Cacique Panchito, a resident of La Ranchería, in the Manuel Tamez municipality, corresponds to an origin from southern America, it has characteristics that have been reported among members of Amerindian communities in the Andes.

Other participants residing in the Yateras area and the Imías municipality led us to a mitochondrial DNA lineage of Amerindian groups such as the Taínos of the Caribbean and some areas of northern South America, specifically of the Karitiana and Surui ethnic groups, originally from Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Colombia and Brazil.

What fields of genetics contributed to the research and how?

Several fields of genetics contributed to the results in the Cuba Indígena research. Clinical genetics, for example, with the creation of the family tree, with the observation and description of the physical characteristics of the study participants, etc. Molecular genetic tools were also used, which allows us, based on genetic markers, to define variations in the DNA sequence and the characteristics of some individuals with respect to others. Population genetics, on the other hand, allowed us to carry out statistical analyses particular to the field of human genetics to analyze the dynamics in the variations of genetic characteristics at the level of communities and populations; there is also genetic epidemiology, which addresses the entire frequency, distribution and patterns of variation of genetic characteristics from generation to generation.

How complex is it to study the genetic origin of a population?

One of the complexities of these investigations is given by their need to be based on markers that cover most of the genome of each person. If we consider that all individual genetic information is a sequence of 6 billion letters, we can have a dimension of how complex it is to study the human genome. In recent years, a type of chips have been designed to study genetic information using hundreds of thousands of genetic markers, which allows us to cover a great deal of the genetic information of each individual.

We used this tool in Cuba Indígena, and we also did sequencing, that is, a detailed reading of the individual DNA sequence and the mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome. The second allowed us to trace the maternal lineages of an individual up to 400 or 500 years ago and that means we can identify where the first woman in the maternal line of the study participants came from. Likewise, the study of the Y chromosome helped us reconstruct the paternal lineages, that is, the paternal genetic signature of these individuals.

What meaning do you attribute, as a doctor, geneticist and Cuban, to the results of Cuba Indígena?

For us, the experience of “Cuba Indígena” has peculiarities that give it special characteristics in our lives as researchers. At the same time, I consider that I have had an enormous privilege as a Cuban doctor and researcher to participate in very special work teams for research in the field of medical genetics, disabilities, and that each of them has had its own differences and mark. The study that we carried out between 2001 and 2006 in the Velasco area with a group of Cuban families who suffer from bipolar disorder was like this. Years later I participated in a team of 34,000 professionals in a study that was carried out on the causes and prevalence of disabilities in our country, which was carried out between 2001 and 2003.

Firstly, it moves me to see that, in the process of characterizing the genetic heritage of our country, it has been possible to continue a work that was started 170 years ago and to see how almost six generations of researchers have tackled with the same interest the search for the visibility of the indigenous imprint (biological, historical and cultural) of Cuban men and women.

As a researcher, being able to contribute and being part of that group of researchers who for almost two centuries did not give up working to make this Amerindian legacy visible in our country is very special.

Another very important meaning of this project and its results is historical. We Cubans grew up learning through history books about the dramatic extermination of the native population of our country. It is true that a majority group of this population was decimated; but perhaps those who wrote that part of our history failed to understand how the Spanish conqueror who arrived in Cuban lands mated and procreated with the Indo-Cuban women of that time, which perpetuated the indigenous genomic imprint for subsequent generations.

Why did women play such an important role in Amerindian genetic survival in Cuba?

Throughout all these years of research we have only found two men whose genetic information reveals that they are descendants of an Indigenous male parent. On the other hand, around a third of the Cubans whom we have studied based on their mitochondrial DNA descend maternally from indigenous women in a path that began up to eighteen generations earlier. In other words, this Amerindian biological legacy transmitted through the mother’s line has been present in the demographic composition of the Cuban population for over five centuries.

From now on, when we write about the origin of the Cuban population and its demographic evolution, we will have to keep in mind what DNA has revealed to us, not only in this research, in which we have found high percentages of Amerindian contribution to the Cuban genome but also from previous studies, in which we had already identified the presence of Amerindian genes in our genetic heritage.

What did you learn from living with these communities during the years the project lasted?

In Cuba Indígena, the study participants were for us a source of knowledge about the use of medicinal plants, about the joy that characterizes them in their daily lives, their resilience; they are partying people, who enjoy sharing with those who come to them. Bonds of deep mutual affection, respect and admiration were generated between our team of researchers and the members of these communities.

Another thing we learned during the study was that a fifth of the genetic information of these people connects us with other regions of the Americas and the Caribbean; which gives us an idea of the biological and cultural ties that unite us with this region.

In particular, in terms of the history of Cuban women, it was also a lesson for us to see how, at the same time that we were reconstructing the life stories, family stories and genealogies of these people we confirmed in the laboratory that women, indigenous mothers were the ones who transferred the most Amerindian genetic information, while those who mostly transferred information of European origin were men.

We learned much more closely how much physical, sexual and psychological violence colonization represented. The majority of women who survived the near extermination of the Cuban indigenous population, in addition to accepting the pain of the loss of their relatives, had to submit to the will of the Spanish men, a pattern that corresponds to a history of colonial and patriarchal domination.

How could the field of genetic research benefit from these results for the prevention of hereditary diseases and the health of the Cuban population in general?

Our research is not intended solely to contribute to history. In terms of preventing hereditary diseases and the health of the Cuban population in general, we now have the possibility of “interrogating” DNA to understand better and interpret who we are. In addition to that, we have the possibility of distinguishing characteristics of the Cuban genome and the particular genetic variants of the island’s population that are derived from that biological history and the mixture between the ancestral groups from which we come. All of this brings us closer to such specific elements as the possible risks and vulnerabilities we have of contracting a certain disease, the individual biological capacity to metabolize certain medications, etc. In other words, from the analysis of the genetic results of “Cuba Indígena” we also derive knowledge about the genetic health of our population that is very valuable in the face of such important challenges in our country as personalized medicine, something we have been working on in recent years in the Cuban Medical Genetics Center.

What was it like sharing the results with the research participants?

Overall, it was a unique experience for me to share the results of the genetic study with the research participants. At that moment we told them how much of their mixture came from a certain ancestral group or another. With Panchito, the Cacique of the La Ranchería community, there was a special circumstance, because he is a revered man and a well-known leader among the communities close to his. When we spoke with him for the first time, we realized that he was a very jovial man, joking and willing to participate in the work. But, in the laboratory the samples are anonymized, which means that, while we are working with them, we do not know who each one belongs to. The sample, at that stage, is nothing more than a number.

When we matched the code with the person’s identity, we were tremendously surprised with Panchito’s results. Although he already had these characteristics of a leader in the community, his physical attributes did not indicate as great a resemblance to the Cuban Amerindian physiognomy as happened, for example, with members of his own family and others. That’s why finding out that his genes had the highest proportion of Amerindian genetic information in the entire study was surprising to us.

I remember that he was already very excited before we even revealed the results to him. He cried and sang a song that he says has been passed down from generation to generation within his family. All of this made that moment very special.

But, in general, with all those with whom we had the opportunity to share the results, we perceived that the study meant for them a confirmation of something, for them real, but that in some sense was doubted. The study came to legitimize what, due to cultural and family heritage, they consider an ancestral treasure.