Cuba in the “handkerchief” of an anole, in a pouch that inflates in the reptile’s neck and attracts the attention of all eyes. The anole or chipojo (Cuban chameleon), as it is popularly known in this country, is above all green, but in its balloon there’s space for a wide-ranging image of figures and colors, of suggestions and even sensations.

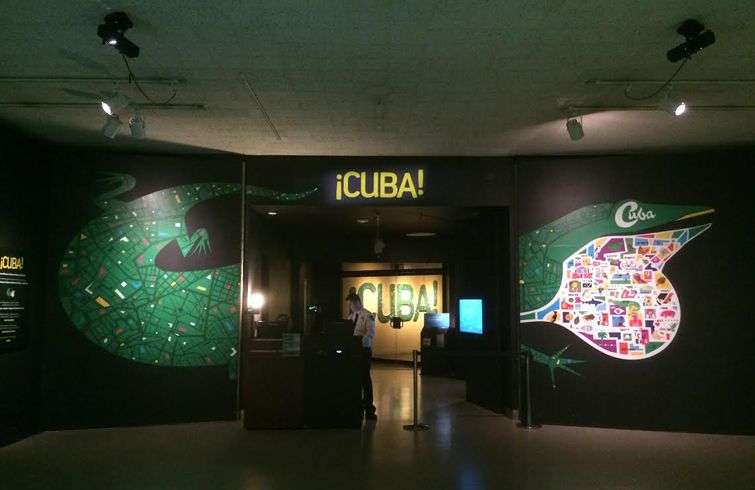

The image is the work of Michelle Miyares, one of the most renowned Cuban designers at present and it has served to promote the exhibition “¡Cuba!”, which opened its doors this Monday in the New York American Museum of Natural History. It offers a wide view of Cuban nature and culture, and is the first major exhibition dedicated to the island in the prestigious U.S. institution. Moreover, it is the museum’s first fully bilingual display.

Miyares is also the creator of several of the posters chosen to make up the exhibition in a section its shares with other relevant designers like Giselle Monzón, Nelson Ponce, Edel Rodríguez (Mola) and Raúl Valdés (Raupa). Her selection pays tribute to the value of contemporary poster making within the extensive panorama of visual arts in Cuba.

In the New York museum’s salons visitors can find other references to this island’s art and society. The vast exhibition comprises from interactive materials and Cuban music videos to a street where a game of dominoes can be played and the aroma of coffee can be taken in, in addition to the famous tobacco leafs, made from paper, and a 1955 Chevrolet that is proof of the ingenuity of Cubans to maintain these cars running.

However, according to Ana Luz Porzencanski, director of the Museum’s Center for Biodiversity and Conservation and the exhibition’s curator, the intention of the display “is to go beyond the headlines about Cuba and show what the people perhaps don’t know or expect.” That’s why, according to what Michelle Miyares said to OnCuba, “the curators’ greatest interest was focused on the great biodiversity of Cuban nature and the state of conservation and protection of certain species and/or areas like the Alejandro de Humboldt Park.”

In order to meet that goal, not only large-scale photos and models of wetlands, forests and coral reefs with their characteristic flora and fauna have been included, but also models of enormous realism of the island’s current or extinct species, among them the giant prehistoric owl, the bee hummingbird, the solenodon and the crocodile. Live animals like the Cuban anole are also on exhibit.

This kaleidoscope, according to Miyares, above all wants to be “a window to take a peek at the island from the United States at a very particular moment of relations between the two countries.” Christopher Raxworthy, also curator-in-charge of the exhibition, agrees with this and recently commented to The New York Times that for a long time the museum had wanted to present a display on Cuba, now facilitated because “the normalization has attracted people’s attention.”

Meanwhile, Ana Luz Porzencanski, although she has recognized her institution’s historic links with the Museum of Natural History of Cuba, a center that collaborated with putting on the display, confirmed that the change of U.S. policy toward the island facilitated the invitation to Cuban colleagues and the granting of visas.

Miyares was personally responsible for the transfer of the chosen posters to New York and later collaborated with the necessary information for setting them up. It was then that she received the proposal of creating an image to promote the exhibition and that’s how the idea came up for the poster with the symbolic and inclusive anole.

“I was very enthusiastic about the challenge and at the same time it was an honor,” says the artist. “The dialogue with the U.S. curators and communication specialists worked well at all times. I presented them with three ideas and they chose the Cuban anole, which is part of the exhibition and I thought it was interesting to explore as a graphic resource, especially because of the structure that we commonly call ‘handkerchief’.”

“Once I started working on the chosen sketch, things started taking shape, until the elements that are shown in the ‘handkerchief’ of the anole remained and which had to be linked to the aspects making up the display. In the end, I am satisfied with what has been done and, at the same time, very grateful to all the museum personnel with which I have had the opportunity to exchange.”

“¡Cuba!” was made in a bit less than two years, less time than the usual for an exhibition of its size and complexity. It will remain open until August 2017 in the New York museum but its life won’t end there, since thanks to the resilience of the materials used it can be displayed in other places in the next 10 years.