A few days ago OnCuba reported the premature death of Ángel Fornier due to a heart attack. The best rower in the country’s history had been a multi-medalist in world cups and a participant in three editions of the Olympic Games, reaching the final in Rio 2016, where he came in sixth.

The also winner of two silver medals (Chingju 2013 and Sarasota 2017) and bronze (Amsterdam 2014) in world championships retired in 2020 due to “personal problems.”

It is frequent to see that high performance athletes abandon their careers, get heart disease or die from this cause. In sports like cycling, heart problems are considered almost “an epidemic.”

In tennis, history includes the case of Arthur Ashe, a member of the Hall of Fame of said discipline. As a consequence of a heart attack, in 1979 he underwent an “open heart” surgery. Four years later they would implant a bypass.1

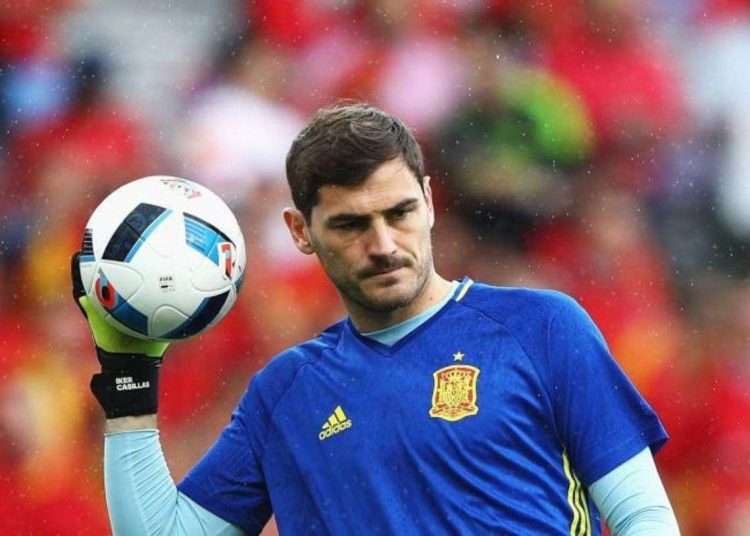

But some of the best-known cases have occurred in the world of soccer. Everyone who in one way or another follows this sport will remember the case of Iker Casillas. The former Spanish goalkeeper, at the end of a training session, began to feel the discomfort of what would be diagnosed as a myocardial infarction. Although he survived without complications, 17 days later he would announce his withdrawal on medical recommendation. There were three days left before he turned 38 years old.

On December 15, 2021, Sergio Agüero, who had signed with Barcelona in May of that year, also retired at the height of his career. In his case, it was not due to a heart attack, but to a dangerous ventricular arrhythmia that took him off the field at just 33 years of age.

Even though sports is so beneficial for health, why do so many elite athletes get heart disease?

Athlete’s heart syndrome

Throughout their careers, the heart of athletes goes through a series of adaptive changes that are grouped together in the so-called “athlete’s heart syndrome.”2

To cope with the demands of physical exercise, and especially resistance and strength training, the body must adapt. In athletes, the volume of blood that the organ needs to pump and the pressures it supports are considerably higher than in other individuals. This is why the number of muscle fibers as well as the thickness of the cells increase. This causes the walls of the heart to also be thicker, allowing it to be more “powerful.”

In addition, the heart rate (HR) decreases; that is, the number of times the heart contracts per minute. With this, the filling time of the ventricles (cavities responsible for pumping blood out of the heart) increases and, with it, the amount of blood that enters and leaves each cycle.

On the other hand, the decrease in HR also ensures that the amount of oxygen needed by the heart muscle decreases. This occurs because, by contracting fewer times, the athlete’s heart has more time to rest; that is, it works less because it is more efficient.

As they are changes that occur over years, the “syndrome” does not usually present symptoms. It is usually in medical examinations where clinical signs of a series of diseases such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, heart valve or rhythm disorders are detected. All associated with the so-called “syndrome.” Athletes must be studied to rule out the presence of any of these diseases.

Up to 20% of high-performance athletes retain some residual increase in heart size after detraining. This has led to the suspicion that the physiological alterations in the cardiovascular system of athletes are not so benign.

In addition, it is a proven fact that high-performance athletes have a higher risk of suffering from atrial fibrillation, one of the arrhythmias that most frequently affect the heart.

Cardiovascular risk factors in athletes

Cardiovascular risk factors favor the onset of heart disease. The practice of sports does not free us from this risk. Some studies determine that half of the young asymptomatic athletes have cardiovascular health problems, such as changes in blood pressure, triglycerides or kidney problems.

When evaluating the cardiovascular risks associated with sports, two large groups must be distinguished: people under 35 years of age and those over 35 years of age. In the first group, the predominant risk factors are genetic. In the second, they are mainly due to bad habits and lifestyles.

On the other hand, sports that require greater oxygen consumption pose greater cardiovascular risk. This is the case of triathlon, speed skating, cycling, boxing and rowing. In them, the heart is subjected to frequent biological stress and a very intense demand for work.

If we add this to genetic risk conditions (for example, the predisposition to develop a cardiac arrhythmia) or acquired (such as having a blood cholesterol level above normal due to diet, alcoholism or smoking), the probability of a cardiovascular event increases.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD), a serious problem

Sports-related sudden cardiac death (SCD) accounts for 75-80% of deaths in young athletes that occurred during competition or training.

SCD occurs up to an hour after the onset of symptoms and is attributable to structural heart disease. That is, to a disease that affects the structure of the heart. It is also possible that it is due, in a structurally healthy heart, to primary electrical disturbances.

For the heart to pump blood, it must generate an electrical impulse that runs through its different structures. This stimulates the contraction of muscle fibers. Alterations in the generation or conduction of this impulse are the causes of heart rhythm disorders. They can be deadly.

Among athletes, SCD occurs in 1.6 per 100,000, while in the general population its incidence is 0.75 per 100,000. It means that it is twice as common among athletes.

The explanation for the phenomenon is that in high-intensity sports, especially during competitions, blood pressure levels are especially high. On the other hand, the consumption of oxygen and the concentration of adrenaline in the blood increases. This combination favors the appearance of heart rhythm disturbances, common in athletes under 35, such as Kun Agüero, or a heart attack in those over that age, such as Iker Casillas.

Fortunately, the occurrence of these phenomena is very low.

Increased risk of death from cardiovascular causes in elite athletes?

High-performance athletes have a 27% lower risk of dying from cardiovascular causes than the general population. An epidemiological study found that Olympic medalists live an average of 2.8 years longer than the general population, regardless of the sport they practice or their country of origin.

On the other hand, a recent study concluded that 96% of the cases of sports-related SCD occurred in recreational athletes. Recreational sports is the one that is practiced for pleasure, health and to obtain a better quality of life.

The most frequent cause of these deaths (63% of the total) was myocardial infarction. This affected men much more than women. Statistically, researchers have found that by age groups and sports, the greatest risks are in individuals aged 35 who play soccer and those who cycle and run after 39 years of age.

An additional risk among recreational athletes is the consumption of anabolic steroids. These substances potentially increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Exercise is not the problem

Because of the visibility they have, the death or retirement of an athlete due to cardiovascular disease may seem more frequent than it really is. It is true that the risk of SCD is higher in athletes than in the general population. But it must be taken into account that the former are a minority group, exposed to greater biological stress than “normal individuals” are exposed to. Therefore, although it seems that the risk of SCD is proportionally greater in athletes, the phenomenon is much more frequent among those who practice sports for recreational purposes.

Should we stop exercising? Absolutely not. The above does not mean that it is not advisable, in terms of health, to practice exercise. Individuals who engage in regular physical activity have a 50% lower risk of myocardial infarction, live longer, reduce the risk of malignant neoplasms, delay the onset of dementia, gain well-being, and minimize the risk of depression.

These benefits are indisputable and it is universally accepted that they far outweigh the risks. It is about adjusting the doses and knowing the body itself to know its potential and limits when exercising.

Doing at least 150 minutes a week of moderate aerobic activity, such as brisk walking, swimming, or mowing the lawn, or 75 minutes a week of vigorous aerobic activity, such as running or aerobic dancing, is always beneficial. Higher intensities, without the supervision of a specialist, may imply an increased risk.

________________________________________

Notes:

1 Coronary artery bypass surgery creates a new pathway for blood to bypass a blocked or partially blocked artery in the heart. This surgery involves using a healthy blood vessel from the chest or leg area. The vessel connects below the blocked artery in the heart. The new pathway improves blood flow to the heart muscle.

2 Athlete’s heart syndrome is not considered a disease and its characterization as a syndrome is also not universally accepted within the medical community.