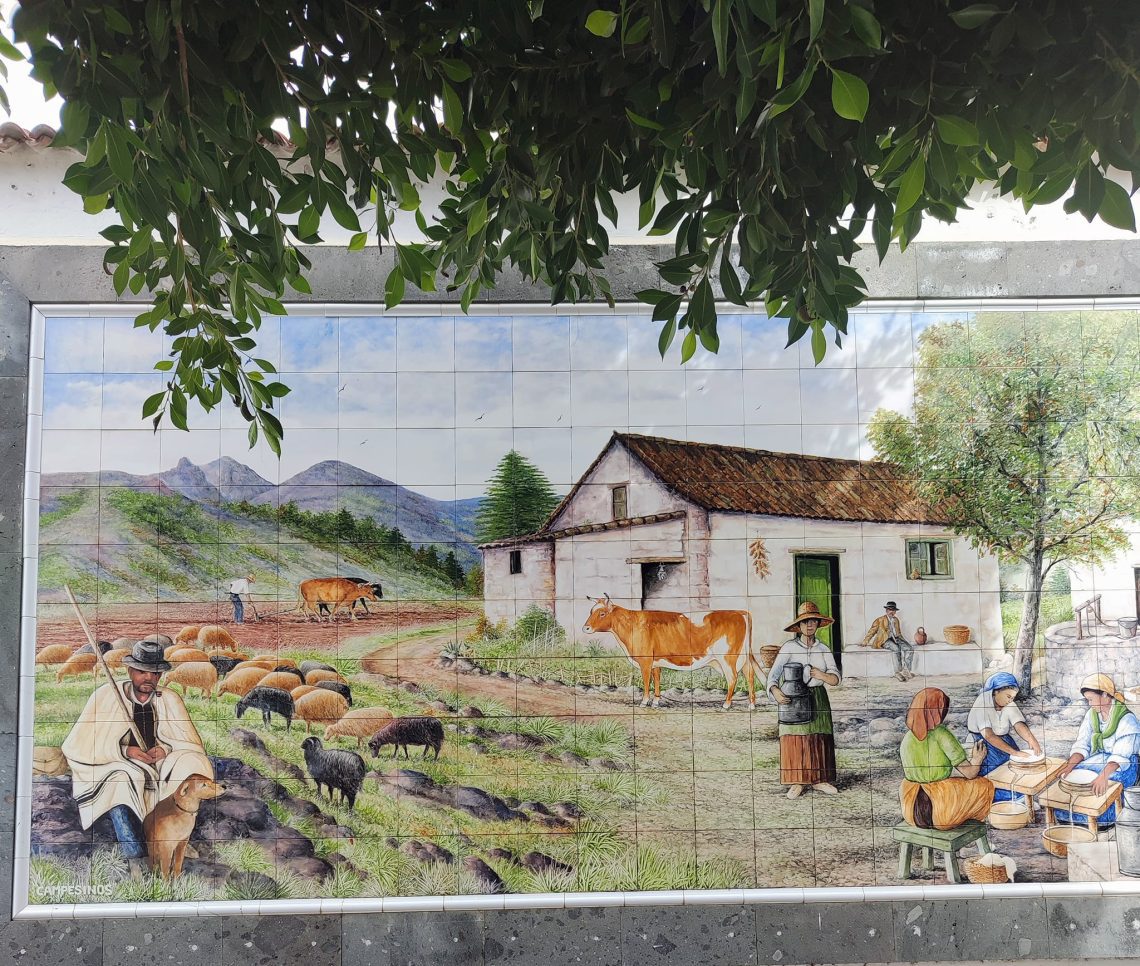

At dawn, we left for the peaks of Gran Canaria in a Global company bus. After a brief stay in Santa Brígida, we continued towards San Mateo. It had rained shortly before and the landscape looked green, with many flowers and farmland planted with potatoes and corn that they call millo here and from which they make gofio, a staple food since time immemorial.

Although I knew that I would not find the exact place where Antonio Pérez Monzón was born, I was excited to be able to walk through old streets and look at those mountains that perhaps he traveled behind a flock of sheep or in the pranks of a child. It was a desire postponed for four years: to visit the land of José Martí’s maternal grandfather.

Antonio was born in La Bodeguilla, de la Vega de San Mateo, on January 29, 1791. He was the son of Salvador Pérez and Leonor Monzón, who had married on April 15, 1782, in the parish of Santa Brígida; they descended from old families in the region. At that time, the majority of men worked since childhood in agriculture. Antonio, however, learned the shoemaker’s trade to earn a living, but he did not work for long in this profession, as he joined the army in Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and later served in Santa Cruz de Tenerife.

It was on this island where he met Rita María Liberata, daughter of Diego Cabrera, a native of Santa Cruz de la Palma, and Mariana Hernández Carrillo, from Tenerife. From the union with Rita, Leonor Pérez Cabrera, the mother of the Apostle of the Independence of Cuba, would be born on December 17, 1828.

Consolación Street

The historian Olivia América Cano, in her essay Como a fuente de vida exhausto río, va a mi madre mi espíritu sombrío, published in 2008, specifies that Leonor was born: (…) in a modest home located on what was then called Calle de la Consolación, very old, narrow and poorly lit, close to the old market. Currently, that street is named after the Canarian intellectual Juan de la Puerta Canseco, and except for a plaque placed by the Canary Cuban Friendship Association and a bust of the sculptor and friend Thelvia Marín, recently donated by the Canarian Association of Cuba to Tenerife, nothing material is preserved from the former Pérez Cabrera family home in Santa Cruz.

To the researcher Leopoldo de la Rosa Olivera, author of an article published in the Revista de Historia Canaria in 1980, we owe interesting data recorded in the military file of Antonio Pérez Monzón:

(…) he was 5 feet and 2 inches tall; with black hair, dark skinned and honeyed eyes. The nose was proportionate, the mouth regular and the forehead spacious. He knew how to read and write… On May 10, 1824, he re-enlisted for another eight years and when his daughter was born, in 1828, he already had the rank of sergeant.

On June 13, 1833, by Royal Order, he received the honorary Cross of Doña María Isabel Luisa. His transfer to Cuba occurred at his own request, which was granted on September 8, 1842. On November 16 of that year, he left for the Caribbean island to join the Havana Artillery Brigade. It is said that he traveled accompanied by his family. He retired as a lieutenant after having completed more than forty-three years of military career.

Martí’s Canarian uncles were named Valentín, José, Joaquina and Rita. It is known that there were two more male children; however, it has not been possible to specify details of their lives. Perhaps they perished prematurely.

Beautiful Moorish eyes

Leonor’s biographer Olivia Cano tells us about her:

Leonor’s cultural environment, outlined from the poverty appreciated in her homeland, perhaps the cause of her foresight and austerity, her education, the typical one of women in the 19th century both in Europe and in America: conditioned by society patriarchal. The feminine space is the small space of the home and her preparation as a future wife and mother of a family are the primary objects of her existence. If we add to this the military status of her father, we will understand that she was rigorously educated in respect for social conventions, and the authority of the father, husband and priest. Even if she learned to read and write, it was because of her natural curiosity and intelligence, since she was never sent to school, as that was not considered necessary for her future. She sewed and embroidered exquisitely, a traditional quality of Canarian women, especially those from Tenerife. She had a pleasant presence and beautiful Moorish eyes, still noticeable, despite her blindness, in the photo from the time of her future trip to New York in 1887.

Was it Leonor who transmitted to her little son stories about the daily life and traditions of the Canary Islands? Or did she know them firsthand when she was a child and was in Santa Cruz de Tenerife with her family? On that island, she turned six years old, as Olivia Cano was able to verify. She was there, in January 1859, because her father Mariano tried unsuccessfully to establish himself, the same would happen to him in Valencia.

Everything is left to our imagination. The truth is that in the text Un juego nuevo y otros viejos, published in La Edad de Oro, Martí wrote:

The islanders of the Canary Islands, who are very strong people, believe that the stick is not an invention of the English, but of the islands; and yes, it is something to see an islander playing with the stick, and making the pinwheel. The same as fighting, which in the Canary Islands they teach children in schools. And the dance of the ribboned stick; which is a very difficult dance in which each man has a ribbon of one color, and he braids and unbraids it around the stick, making bows and funny figures, without ever making a mistake.

Grandfather and grandson

Apparently, Antonio Pérez Monzón died in Havana at the end of the 1850s so he was able to meet his grandson Pepe, born on January 28, 1853. Leonor also died in the Cuban capital, on June 19, 1907.

The immigrants from the Fortunate Islands proudly highlighted the Canarian origin of José Martí’s maternal family through articles, civic acts, and other tributes. Among several texts that we have found in the collections of magazines published in Havana, we reproduce, as a sample sample, one published by El Guanche, on January 25, 1925:

On the 28th of this month marks sixty-two years since his birth. He carried in his entrails an islander, a Canary Islander whose name bears the street where the humble little house is located where the greatest of all Cubans and one of the most illustrious sons of America and the world first saw the light. Martí is Cuba’s, he belongs to Cuba, and it is his most positive glory. But he is also ours. And if there were no close bonds of affection between Cubans and Canarians, the memory of the unequaled Apostle would be enough to create and strengthen them.

________________________________________

Sources:

Olivia América Cano Castro: “Como a fuente de vida exhausto río, va a mi madre mi espíritu sombrío,” Revista Brasileira do Caribe, vol. VIII, no. 16, January-June, 2008, pp. 363-375, Universidade Federal de Goiás Goiânia, Brazil.

Leopoldo de la Rosa Olivera: “La familia materna de José Martí,” Revista de Historia Canaria, Volume 37. Year 48, Number 172, La Laguna de Tenerife, 1980.

El Guanche

www.ancestry.com