This column recently wrote about the Marianao dances as a summertime recreational option for Havana residents in the 19th century and up until the 1950s.

Another old custom, in order to alleviate the effects of the heat, was for wealthy families to spend time in their country houses or rent one of those large mansions surrounded by trees, sometimes near a river or the sea, where they enjoyed horseback riding, board games, and abundant fruit.

Groups would go horseback riding to towns near the city or ride in horse-drawn carriages. Those with ample income traveled abroad. It was the ultimate experience.

Some, tempted by what people said, by the harmful custom of appearances’ sake, so deeply rooted, if they couldn’t go to Europe and the United States, would make it up. A piece written by the chronicler Cesar Cancio, published in El Fígaro in 1889, said:

“Many families disappear from Havana and leave cards for their acquaintances saying goodbye because they were going to Paris; but instead went to the countryside for a hunt, or a luncheon, or a hideaway, and the first thing you do is notice that on this little farm or that farm, under a light thatched-roofed house, is the family everyone thinks is in Paris, eating their guts out and biting their nails and with a dog’s face. And this is a family morally dead forever, and its very friends are the Zacatecas who lead it to the grave of ridicule, accompanied by mockery and the use of metaphors.”

Don Cándido’s baths

The medicinal baths in the mineral waters that flowed from springs in Madruga, Guanabacoa, Santa María del Rosario, San Diego and Marianao also attracted summer vacationers.

By the second half of the 19th century, another option had become established: sea bathing, which, due to its proximity to the city, was more feasible.

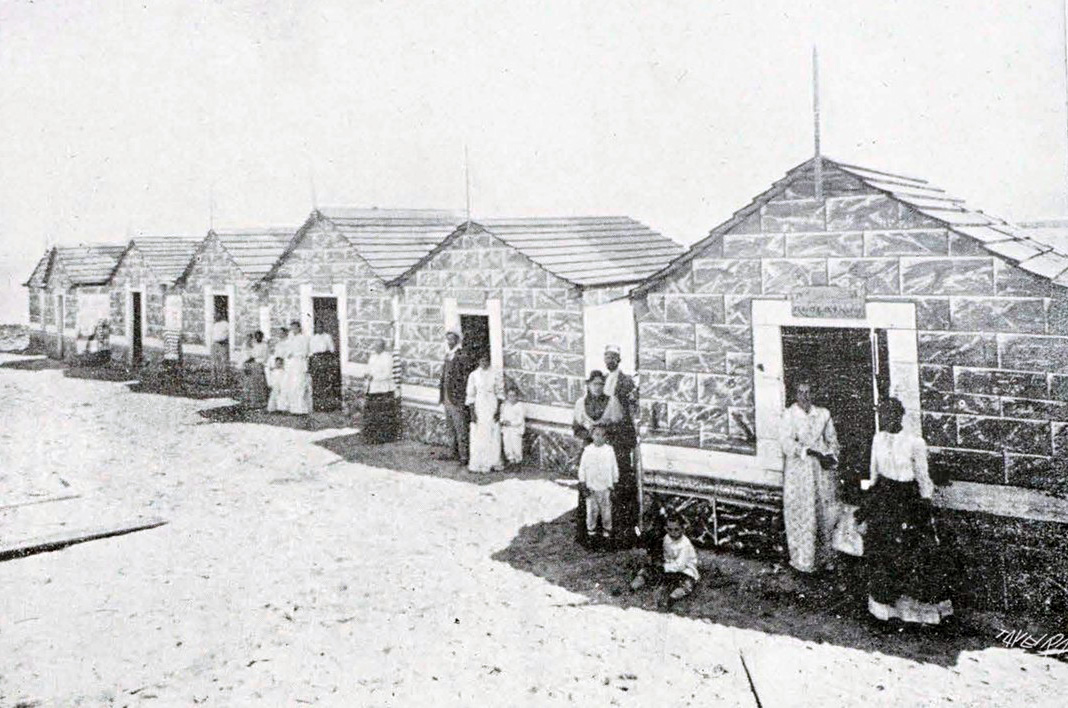

In the summer of 1895, the Third War of Independence was taking place in Cuba, which had begun on February 24 of that year. Amid the tension of the conflict, businessman Cándido Gómez was promoting his business in Havana: a beach resort on Marianao beach, where he had several cabins, refurbished for the occasion.

“These Marianao baths have always been famous for their strong breeze and clean waters, perfectly hygienic due to their location far from any spot where horses are bathed and trash is thrown. But despite their perfect isolation and admirable natural conditions, it must be admitted that they had been somewhat neglected until Mr. Cándido Gómez, their current owner, has undertaken significant works and introduced renovations that surely make them comparable with the best of their kind in the United States and Europe,” announced El Fígaro, with a photo illustrating the changes that had taken place in Cándido’s venture.

The season began on June 1. To reserve 30 private baths, one had to pay 3 pesos; a private bath cost 15 cents, and a public bath cost 10 cents.

By train

Transportation was guaranteed thanks to the efficiency of the railway company managed by John A. McLean, which increased the number of trips to Marianao beach starting on May 15. In 1887, a train departed from Concha Station to the Samá stop (in the town of Marianao) every hour from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., later at 9:30 a.m., 10:30 a.m., and the last at 12:30 a.m.

From Concha to the beach, via a branch line, they departed every hour from 6:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. The day was rounded off by two night trips, at 9:30 p.m. and 10:30 p.m. From Marianao to the beach, they planned itineraries every hour, from 5:30 a.m. to 8:30 p.m., with two extra trips, at 10:30 p.m. and 11:30 p.m.

An announcement published in the Diario de la Marina added:

“So that residents of Havana and surrounding towns can use the amenities of the beach, the Company Administration will sell passes for 30 round-trip first-class rides, including a reserved bathroom, at the following prices: from Concha, 16 gold pesos; Tulipán and Cerro, 15 gold pesos; Puentes and Ceiba, 13.75; Quemados and Samá, 7.50.”

The Vedado baths

Although the El Progreso baths, located on E Street and the Malecón in Vedado, reached their greatest splendor in the early decades of the 20th century, they were already a recreational site in the previous century. And there were others. Our colleague Ciro Bianchi tells us:

“Around 1895, there was notable development in ‘the charming village of El Vedado,’ as the poet Julián del Casal calls it in one of his chronicles. The proximity of the sea made the area gain importance. Along the coastline, from G to 6, several beach resorts were established around 1864. E Street was popularly known as Baños (Baths) because it led to the pools of the El Progreso beach resort. Another of these establishments, Las Playas, was located at the end of D Street, while the Carneado baths were located on what today would be Malecón and Paseo streets. People bathed at the time in what were called drowning pools, which took advantage of the arrangement of the rocks or were artificially dug into them. There were small ones, with places reserved for the family, and others, very large, where men and women bathed separately.”

In 1890, La Unión Constitucional announced that El Progreso had, in addition to the public pools, a splendid hall for family gatherings, matinees, dances, and retreats.

The building’s owner built independent apartments for families on the second floor, with a living room, dining room, three bedrooms, a kitchen, and a toilet, furnished or unfurnished, according to the client’s taste. On the ground floor, there were rooms for single men.

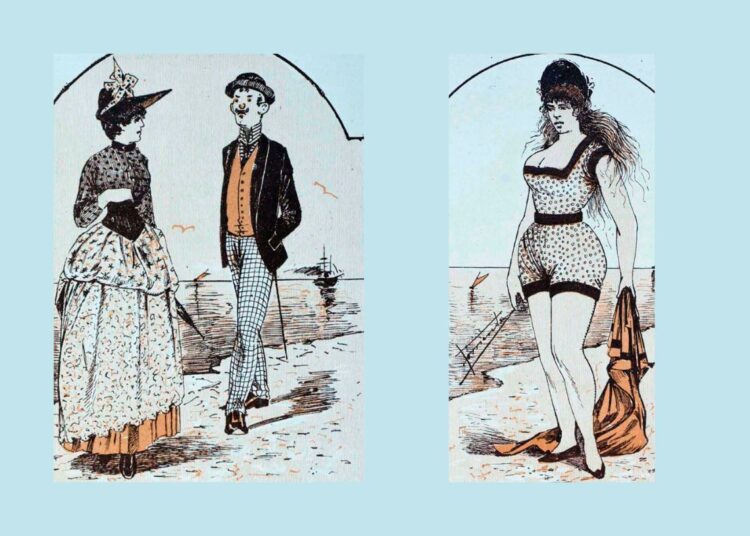

A peek at the neighbor

Those who couldn’t afford private baths at the San Lázaro resorts wouldn’t stop going, as chronicler Wenceslao Gálvez jokingly said in 1894, “to show off that they were bathing and to see if the neighbor was wearing a darned stocking or cotton camisoles with sleeves. This is the plague of the resort. The others who show themselves, just as they are, in the bath, without blush or makeup, don’t compromise with those who only come to see and gossip about what they’ve seen and what they haven’t seen.”

The names of the baths most frequently promoted in the press were: Elíseos, Las Delicias (also known as De la Isleña), San Rafael, Romaguera, Militares, Saratoga, de Miguel, among others.

The pools were covered by “flimsy sheds…whose zinc roofs would flap in the air at the first gust of hurricane-force wind,” Federico Villoch recalled in one of his Viejas postales descoloridas. Near these establishments, houses were rented to summer season vacationers.

Cojímar

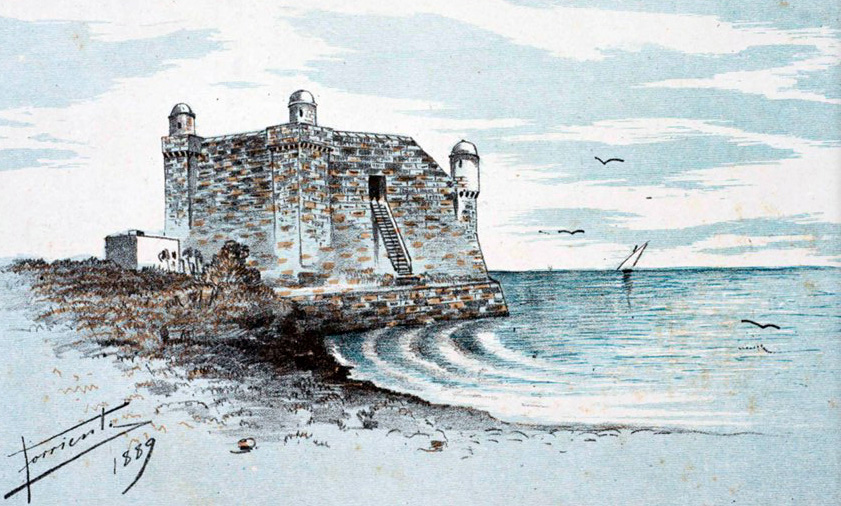

In those distant times, the beaches of Santa Cruz and Cojímar were gaining popularity.

Francisco Tabernilla and Arturo Fonts, local promoters of the picturesque Cojímar beach resort, organized excursions from Havana and worked to improve the site’s infrastructure.

Journalist Fernando G. Campoamor, in one of his scenes published in Opina, noted: “Using a phrase common to our great-grandparents, the Boca de Cojímar area was ‘of a healthy and benign temperament, and its surroundings had a cheerful appearance.’”

This healthy climate and beautiful scenery, along with abundant game hunting and swimming in the calm harbor, made it a refuge for short breaks during the summers and the setting for pleasant outings, even though it only had one street, the classic Calle Real of all the King’s towns.

By 1846, there were 184 residents with some mixed shops and some masonry houses. Later, they added eight streets and even an avenue — also known as the Calzada Real — and paved the old horse and cart path that took them out of their inlet.”

Tourists traveled from Havana by train to Guanabacoa. At the bus stop, the so-called guaguas, carriages pulled by mules and horses, waited. The avenue was almost always in poor condition and, since the climb up the hill was difficult, passengers sometimes had to get off to lighten their load and, if necessary, push the guagua.

In 1895, the number of pools was increased, and the Hotel Mortera continued to provide services. Already at that time, as a columnist in the Diario de la Marina would say, “going to Cojímar is like going to heaven, because life is wonderful there.”

________________________________________

Sources:

Cuba y América

Diario de la Marina

El Fígaro

Opina

Unión Constitutional

Archive of the Office of the City of Havana Historian