Perhaps the first French who arrived on the coast of Matanzas were privateers, when only herds, corrals and ranches existed in there. They arrived furtively to carry out smuggling with the landowners of the region. Alonso Suárez Toledo was one of the wealthy people who supplied the outlaws, for more than 25 years, with corn, meat, cassava, hides, tallow and honey.

Even King Carlos I knew about that illegal trade and ordered that the Suárez Toledo livestock farm, located near Matanzas Bay, be removed to another more remote area.

The mandate was not fulfilled, says researcher Francisco P. Domínguez, and the name of the disobedient returned to the public spotlight on December 15, 1576, when it was discovered that the French ship El Príncipe had taken supplies on his properties.

Since it was founded in 1693 by thirty-six families from the Canary Islands, the city of Matanzas would constantly receive the European migratory flow during the colonial period.

The islanders were later joined by Catalans and French. The most significant wave of the latter occurred during the stage of the Haitian revolution (1791-1804). With experience in agriculture, they produced coffee, sugar cane and even tried planting cacao.

They settled in the Matanzas jurisdiction in Canímar, Limonar, Ceiba Mocha, Camarioca and Cárdenas. History records the Laurent, Leclerc, Villére, Lajonchere, Bacot, La Tardie, La Vallet, Ebusselau, Gaunaurd, Tolón, Verrier, among others.

The most emblematic case was that of San Juan de Dios de Cárdenas, founded on March 8, 1828, which had among its first inhabitants the settlers Enrique Albrech, the Count of Lajonchere, and Juan Pedro Biart de Bauregard. Francisco Samuel Aymeé and Luisa Constancia Michel.

Next to this urban center was the Magnolia coffee plantation, where the Napoleonic painter and collector Juan Bautista Leclerc de Beumeel, son of Juan Leclerc, was born in 1809, who arrived in the region at the end of the 17th century, according to a study by researcher Ernesto Blanco Alvarez.

The plastic artist was director of the San Alejandro Academy in Havana. Like him, many direct descendants of the French would make notable contributions to Cuban national culture.

In the sugar industry

In the mid-19th century, the decline in coffee production was evident, given the rise of the sugar industry. The knowledge of the French would contribute to the development of this economic activity; especially engineer Charles Derosne, “who applied his knowledge manufacturing equipment for the sugar cane industry, and arrived in Cuba in 1843 to supervise the installation of the first vacuum evaporator, at the San Juan Nepomuceno sugar mill — known such as La Mella — in Limonar, and, in other cases, applying recognized inventions, such as the test, in 1850, of a triple-effect evaporator at the Álava sugar mill, in Colón. The French contributed new and better varieties of seeds and important techniques such as water mills, turners, new energy transmission systems (steam power), the dissemination of the use of the so-called French or Jamaican train, the use of the hydrometer, horizontal mills, clay lasts, flat tiles (which are still called French today) and centrifugal tiles,” says researcher Armando Castañeda Lozano.

Alejandro B. C. Dumont, former army officer who emigrated in 1804 from Haiti, in addition to introducing techniques for the cultivation of coffee, sugar cane and pineapple, published in 1822 the book Consideraciones sobre el cultivo del café en esta Isla.

A notable personality was the doctor Honoré Bernard de Chateausalins, who lived in Matanzas from 1831 to 1842. Author of studies on cholera and other diseases, published in scientific journals, as well as the book El vademécum de los hacendados cubanos, which had four editions. The text, academic Miguel Ángel Puig-Samper tells us, is a “manual to cure black slaves, but also useful for them and their families, as it includes the description and medications applicable to very common diseases in those times, not only among slaves, but also in the population in general, among them convulsions or seizures in children, abundant in whites as well as in people of color, the so-called “seven-day disease” (infantile tetanus), parasitism, dysenteries, venereal diseases, hysteria and hypochondria, uncommon among the peasant population and black slaves, but common in his opinion among civilized and rich people.”

The wise Miguel Du Brocq, descendant of a noble family from Bayonne, also left his imprint. This surveyor created plans that contributed to the construction and improvement of roads in the province.

Engineer Jules Sagebien

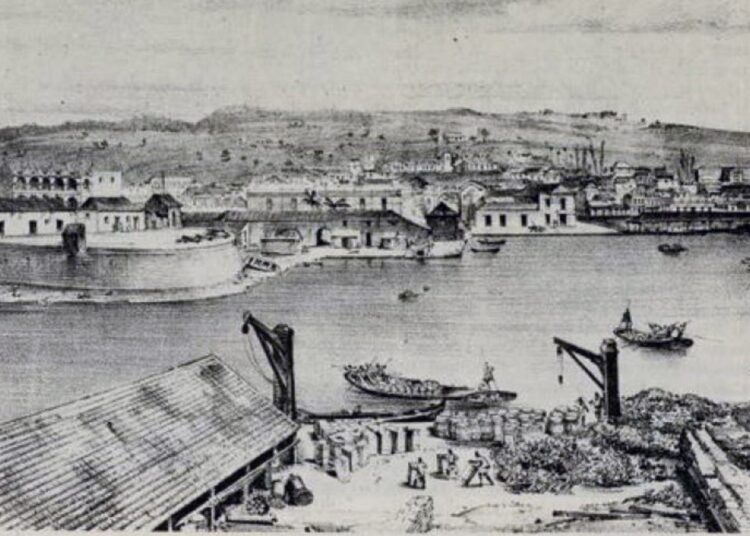

Many French also dedicated themselves to commerce and the arts in the 19th century. In 1818, Esteban Best and Julio Sagebien built the Customs building in the city of Matanzas, the first large-scale neoclassical work in Cuba, in the opinion of Dr. Alicia García Santana.

The imprint of Julio Sagebien (1796-1867) is more comprehensive. Married in 1824 to Demetria Josefa Delgado Guerra from Matanzas, other buildings are due to his talent: the Yumurí bridge (together with Eloy Navia), the reconstruction of a bridge located at the mouth of the San Juan River, and the construction of another, named La Carnicería, on the same tributary.

This engineer and architect also carried out the projects and directed the execution of the Santa Cristina Barracks, the Santa Isabel Hospital, the Prison building, and a home for landowner Juan Bautista Coffigny.

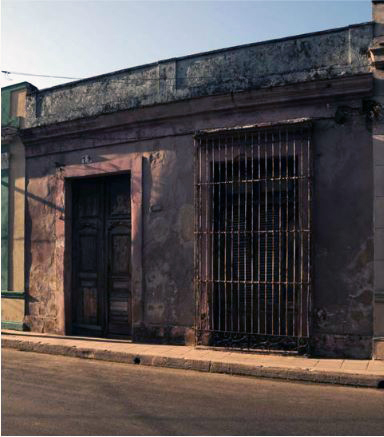

Dr. Ernesto Triolet Lelievre left a century-old legacy that has transcended national borders: the famous French Pharmacy, founded with his colleague Juan Fermín de Figueroa y Velis on January 1, 1882 in the Plaza de Armas of the city of Matanzas. In old newspapers we find advertisements for the formulas prepared in its laboratory: Simple Ant Syrup, Compound Coffee, Orange Blossom Water, Quina Aromatic Wine, Sodium Bromide Solution, Scorpion Oil, Tranquil Balm, Benzoin Tincture, Fluid Extract of Belladonna, among others.

This three-story building, due to its heritage values, was converted into the Pharmaceutical Museum of Matanzas in 1964 and declared a National Monument on November 20, 2007. It is the only French pharmacy from the late 19th century preserved in the world.

It is difficult for the French not to expand the exquisiteness of their fashion wherever they live. Agustine Rouly de Verrier, in the 19th century, inaugurated a business with the latest products produced in Parisian workshops and, it is said, she also contributed to the cultural life in the City of Bridges as a promoter or manager.

The French literary texts, translated into Spanish and published in the city’s printing presses, Italian traveler Adolfo Dollero affirms, “had an indisputable influence on the customs and civilization of Matanzas.” The teaching of Victor Hugo’s language in private schools and by teachers in their homes favored the spread of the language; mastering it gave distinction and class.

The Versailles neighborhood

According to historian Francisco P. Domínguez, the name of the neighborhood is due to the cultured José Teurbe Tolón, landowner in the area, who came up with the idea to pay tribute to his French ancestors “and also as a seal of social distinction to the neighbors, all addicted to the spirit and fashion radiated by the halls of what was the court of the Sun King.”

A census from 1860, prepared by the neighborhood watchmen, illustrates the importance that the district acquired. Of the 29,084 inhabitants of the city in 1860, 2,783 resided in Versailles.

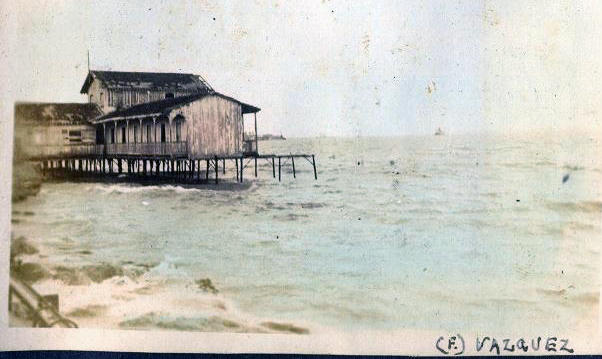

Adolfo Dollero, in the 1910s, visited Matanzas and wrote a book, published in 1919, that we can classify as something between a travel chronicle and a historical study, with more weight on the latter.

He described Versailles like this: “it does not resemble the luxurious residence of the kings of France, from which it has taken its name; and yet with its Castle and its old bridge, its wide Martí promenade that deserves to be more cared for and more frequented, its old Hospital and its flower and pigeon nests, it is extremely picturesque.”

In the first decades of the 20th century, the decline in the number of French was noticeable. Of the 3,000, including natives and their descendants, that the Consulate of that nation in Matanzas once had registered, many had died, or had moved to another place. However, there was a deep, lasting imprint on the Athens of Cuba.

________________________________________

Sources:

Adolfo Dollero: Cultura Cubana. (La provincia de Matanzas y su evolución), Seoane y Fernández printing presse, Havana, 1919.

Raúl R. Ruiz: Memoria francesa, Vigía publishers, Matanzas, 1996.

Francisco J. Ponte y Domínguez: Matanzas, biografía de una provincia, Cuban Academy of History, 1959.

Ernesto Blanco Álvarez: “Juan Bautista Leclerc de Beaume: un olvidado artista de la plástica cubano–francés.”

Armando Castañeda Lozano: “Presencia francesa en el despegue y auge de la economía de plantación esclavista en Matanzas.”

Marcia Brito Hernández, “Joya patrimonial en medio siglo de conservación.”

Alicia García: “Julio Sagebien, arquitecto de Matanzas, ingeniero de Cuba,” in Arquitectura y Urbanismo, volume XXXII, No. 1/2011.

Miguel Ángel Puig-Samper: “Dos Hipócrates negreros en Cuba y Brasil: Bernard de Chateausalins y Jean-Baptiste Imbert.”

El Reino: diario de la tarde.

La Correspondencia de España.