Born in Huelva, Spain, until very recently Héctor Garrido did not realize that in his genetic code, he carried a discreet, but notable — especially because of its improbability — 1% of Amerindian genes.

The photographic work of the man from Huelva, now a resident in Cuba, is vast and eloquent. His career, particularly his specialization in scientific and aerial photography, has taken him to the most remote places on planet Earth. Neither the Sahara Desert, Patagonia or Antarctica are indifferent to his nomadic lens.

But, of all his work, the one that moves me the most is the one that Garrido has dedicated for years to answering the question that I, no matter how much the history books insisted on its nonsense, never stopped asking myself: Is the indigenous imprint alive in Cuba?

Moved by this curiosity that Dr. Alejandro Hartmann, historian of the city of Baracoa, planted in him, in 2018 he embarked on an adventure in which science and photography went up the Toa River, in search of answers.

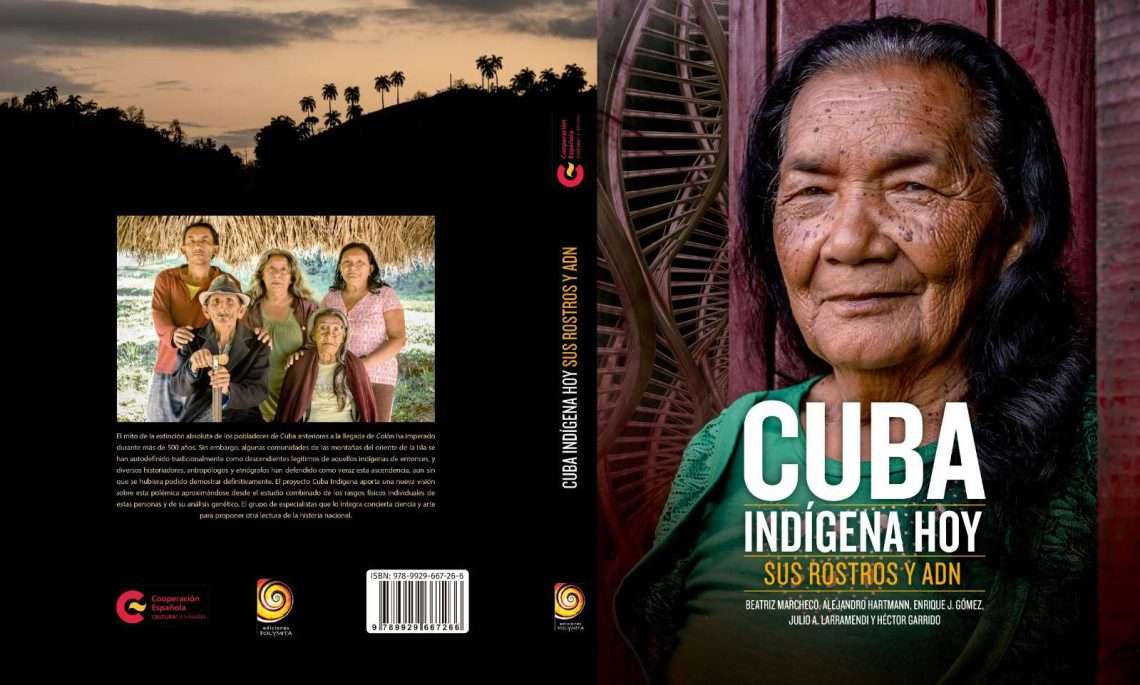

The Cuba Indígena Project, whose results were made public in 2022, leaves no room for doubt: the island’s indigenous descendants found a way to resist the most diverse elements for centuries, including those of a biased historical narrative that had been denied to them — and to us — until today, the illusion of vindicating it.

OnCuba spoke with Garrido, the project’s director, about its emergence and future directions.

A how, a when and a why

The initial proposal made to me by Dr. Alejandro Hartmann, historian of the city of Baracoa, was to make a photographic series that would show the survival of indigenous descendants in eastern Cuba. Hartmann had been working for years on the identification of Amerindian descendants in the region and for him it was important to make that reality public. The objective was to demonstrate that, contrary to the belief of their absolute extinction, there were still important nuclei in certain indigenous communities in the mountainous areas of the eastern provinces of the island.

The idea was very interesting, but his approach was insufficient, since a photograph, by itself, cannot indisputably demonstrate a fact of such complexity. That is why I decided to structure a great project that would give definitive answers and that would involve, in addition to photography, science. This is how the Cuba Indígena Project was born. It was almost completely designed in a single night of work, after visiting the communities in Baracoa at the beginning of 2018.

The involvement of comparative genetics (a branch that studies the differences in the genomes of individuals of the same species) was the cornerstone that would differentiate the project from so many previous ones that had been carried out.

In addition, a historical-documentary, ethnographic and anthropological approach to the communities would be carried out. And in each of these specialties we had to incorporate the most renowned people in each field. Thus, in addition to Alejandro Hartmann, Dr. Beatriz Marcheco (medical geneticist, Director of the National Center for Medical Genetics of Cuba), Enrique Gómez Cabezas (sociologist, from the Center for Psychological and Sociological Research-CIPS), Julio Larramendi (photographer, researcher and editor) and, partially, José Barreiro (anthropologist).

In search of faces

The first time we went up with Hartmann to the mountains of Baracoa in search of indigenous descendants was in 2018. We had gone before, on more than one occasion, but never with the intention of carrying out a project of this type.

After that, a dozen expeditions have been carried out, many of them merely exploratory with the intention of looking for new communities and others to study and work in known ones. The expeditions have been of varying duration. The ones that have lasted the least have taken us ten days. The longest lasted two and a half months.

At first, we worked on the catalog that Hartmann and Barreiro had compiled for thirty years and that makes up what is now known as “the great Indo-Cuban family.” But once we visited all these communities, we widened our search, convinced that there were more. Thus, sometimes we traveled to a community of which we had some reference (bibliographical, documentary, or even by word of mouth).

Other times we randomly asked within those regions that we considered to be highly likely to host communities of Amerindian descendants. We are talking about the Sierra Maestra, the San Andrés and Yateras valleys, the entire Baracoa region, the Barién area, Dos Ríos, La Jatía; they are spaces that have been fundamental for the results that the project has obtained.

Cuba Indígena highlighted and documented the vitality of Amerindian culture on the island, something that we Cubans thought was lost. What was it like witnessing the process and recording it in images?

Many researchers had pointed to the presence of indigenous descent in some of the areas in which we have worked. They built the foundations on which the Cuba Indígena Project has been based.

Beyond this, it is very important to point out that many of these communities never lost their indigenous identity; in other words, the tradition, inherited from their ancestors, of remembering that above all they were indigenous, descendants of Amerindians, endured among them. And that’s how they identify themselves.

I remember Panchito, the Cacique of the Mountain, narrating how his grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents defended that they were Amerindians and asked their descendants to never forget that, even though that fact was denied to them by society.

That awareness, defended for more than five hundred years, is an intangible but highly important legacy. Although a good part of the cultural trace has been lost and even the members of these communities present racial mixtures in their genetics — like the majority of human beings in this global world —, they have a awareness that groups them and has made them endure and identify themselves as Amerindians to this day.

It took five years and six expeditions in search of the Rojas, the Ramírez, the Romero and the Rivera of eastern Cuba. How did your creative process coexist with the researchers’ routine in the field?

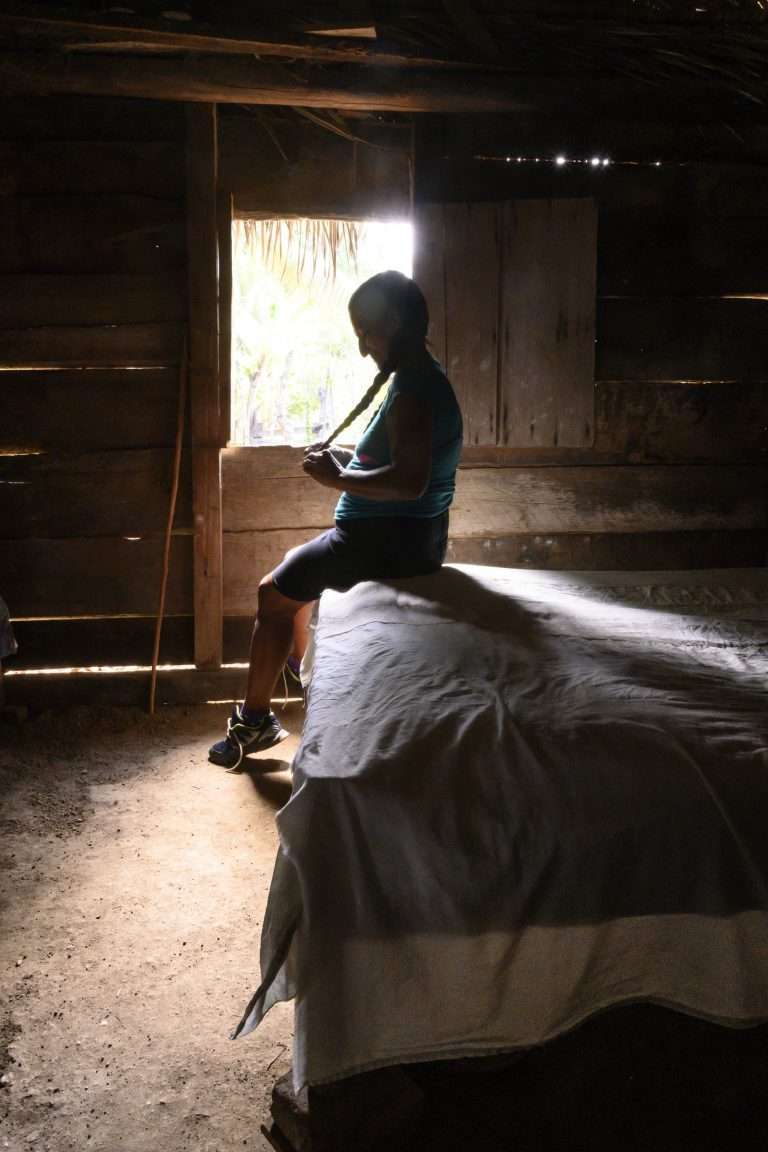

During this time, different creative moments took place, marked by the closeness or familiarity that arose between the communities and the project team. Time has been uniting and mixing us. Coexistence has caused the limits to be diluted and, in the end, the inhabitants of the mountain feel that they are an active part of the project.

For their part, the members of Cuba Indígena have cohabited in equality in the communities. They joined the daily work.

The most important moment was coexistence for two and a half months at the time we were filming the documentary, directed by Ernesto Daranas. From all this, a powerful relationship was born that has become somewhat familiar. It will last forever.

The function of photography in the project was not passive or limited to collecting the visual memory of the living indigenous communities in Cuba. Your work and that of Julio Larramendi contributed actively by offering analysts an instrument (the photo) for the study of the phenotype of the inhabitants of the communities. Tell us a little about this experience.

That’s right. Photography was used as artistic material and work tool. In this way, the phenotyping of each person who underwent the DNA study was carried out through photographs. The photographs were taken in identical lighting conditions, against a uniform white background, along with a color pattern chart and centimeter scale. First from the front, then in profile. At the same time, Julio Larramendi took photographs of the environment in which the members of the communities lived, their routines, as ethno-anthropological documentation: what their houses are like, how they cook, what tools they use, etc.

Did you have similar work experiences? Did you have any creative challenges?

During the years that I worked for the Higher Council for Scientific Research of Spain, I carried out photographic accompaniment to a good number of expeditions to different parts of the world: Australia, Patagonia, Antarctica, the Maghreb, the Sahara Desert…and I also developed my own projects, which entailed this type of exploratory voyages in different countries and under generally quite extreme conditions.

Creative challenges are an integral part of this type of work. Sometimes you have to face very difficult conditions, both environmental and technical. The most important thing is that the human work teams are well selected so that they can carry out their work with cohesion.

There is a fundamental part, which is the preparation and production of the expeditions. Generally, there is a team of people who do this support work before and during the journeys, sometimes from a distance. It is important that a well-drawn roadmap exists, to never lose sight of what the objectives are and direct all the efforts of the team to achieve them.

What is kept alive from the Taino, Siboney and Guanajatabeye worldviews in these communities?

Actually, in the set of communities what we could call a small cultural heritage is maintained, but which is actually common to many peoples of Cuba and the Caribbean in general. We are talking, for example, about the use of the royal palm tree for the construction of houses (bohíos), food and medicine. Also, of some culinary formulas — casabe, for example —, the use of medicinal plants and magical-natural remedies, the manufacture of implements from plant elements — such as guano cutaras; punctually the touch of the guamica, the survival of the coa, etc.

In addition to that, in the Ranchería community, a cult of respect for the land and nature is especially professed. A series of rituals are carried out that have tobacco at their center.

We cannot know for sure the origin of these ceremonies, how much has really been kept alive and how much, in the end, is supervened or created after the miscegenation. What is certain is that today all of the above is an indisputable hallmark of these communities. They are knowledge and rituals that are perpetuated from generation to generation, so we can talk about culture, regardless of the time that its members have been carrying out each of these manifestations.

In most cases, these are communities supported by small-scale agriculture and are part of the social fabric of the region, as much as the others. The main difference is the marked group identity and the identification of the figure of the Cacique as an entity of respect, which is assumed by all members of the community.

When the results of the study were made public, we had access to a moving image of your authorship in which the Cacique of the Mountain and leader of the community of La Ranchería, Panchito, received the results of his genetic test, which showed his Taíno ancestry. How was it like to witness the moment? How was it for you to meet and photograph a Cuban Cacique?

The Cacique of the Mountain, Francisco Ramírez, Panchito, is, to date, the person with the highest percentage of DNA of Amerindian origin of all those analyzed in our study and in all known studies in Cuba.

He has dedicated his life to uniting mountain communities and creating strong bonds between them, which transcend family affiliation.

His legacy is the identification of the group that these communities have been building in the last half-century. He received from his grandfather the commission to be the Cacique, even as a child, because he stood out in his spirituality, closely linked to Mother Earth.

During the last five hundred years, generation after generation, the members of these communities have kept alive the idea that they are descendants of indigenous peoples, that they are Amerindians, first and foremost. But history, both the successive versions of the historical narration, as well as the historical present, has denied that origin.

Various researchers of different nationalities have tried to give definitive answers on successive occasions, without their conclusions having been able to definitively agree with those who considered themselves Amerindians. And the day came when we met at La Ranchería with the Cacique of the Mountain to open the envelope that contained the results of his DNA test, which we had carried out for our project months before.

It was a magical and very beautiful moment and, luckily, we were able to film it for the documentary that Ernesto Daranas is making.

Before Dr. Beatriz Marcheco began to reveal the results, the Cacique Panchito burst into tears. It was like a cry that he emanated after five hundred years held back by waiting; it was the cry of many generations of Amerindians, of grandparents, great-grandparents, great-great-grandparents, and so on, until the times when the Europeans came to sully “the most beautiful land that human eyes have seen.”

At that moment, along with his wife and his children, Panchito was breaking the curse that had made them invisible in the eyes of society. Dr. Marcheco confirmed what they had known for so long: they really were Amerindian descendants. That day his genetics revealed a rich treasure, patiently guarded for more than half a millennium.

During the expeditions, the members of the team also underwent genetic tests. To you, these tests revealed an unexpected result about your ancestry. What was it like to discover your Arawak origin?

It was at a public event in Spain, shortly before the pandemic. Dr. Marcheco presented, for the first time, various results of the project. She began to give details about the ancestry of the participants and, suddenly, she proposed a game with the public. It consisted of guessing the genetic mix of each of those present at the panel of speakers. After playing this riddle for a while, to everyone’s surprise — and even more so to mine — the doctor presented my results.

They showed an old Amerindian ancestry, small, very small, but clear: more than 1%. Apparently, my family descends from an Arawak woman who had children in the early 18th century.

It was absolutely unexpected and adds a link, between magical and poetic, to my involvement in the project. It’s something I’ve been proud of ever since. Personally, the project has become a way of paying homage to Amerindian ancestors I never got to know. And it unites me more, if possible, with the inhabitants of the mountain, now in a truly familiar way.

Beyond the publication of the book, the photos and the documentary, in what ways can the project contribute to the reparation and preservation of our original peoples and to the awakening of the institutions?

I think it is time to continue and complete the investigations. This project has barely uncovered a part of the genetic and cultural treasure that is hidden in the mountains of eastern Cuba. There is still a lot of work to do. Dr. Beatriz Marcheco, for her part, has a very interesting roadmap ahead of her. We are in search of economic funds so that she can complete it from the National Center for Medical Genetics, which she directs. It can still contribute a lot of new information that will enrich the knowledge about the ancestors of this beautiful island and about the transgenerational identity of Cuba.

Will the photographs taken by you and by Julio Larramendi be exhibited in Cuba?

They were exhibited during the pandemic on a few occasions, both in Cuba and in Spain, in a small traveling exhibition under the title Aborígenes. New exhibits will probably take place shortly.

What lessons did you learn from living with these communities during the five years of the project?

It has been a very important experience for me. Today we live far removed from this way of life. We are locked in our cities and within them in our neighborhoods and in our small apartments, judging the neighbors, with whom we share life, as enemies.

There is no collaborative concept of coexistence, as in mountain communities, where the limits of the private are blurred in favor of the group. The generosity and kindness of the mountain people have touched me deeply. These years, of course, have been a time of learning and growing together with people who I now consider my family.

Cuba Indígena is a photography and science project that explores the possible existence of living indigenous descendants in Cuba. From it they have derived a book, published in 2022 by Editorial Polymita, and various photographic exhibitions. A documentary by Cuban filmmaker Ernesto Daranas is in the process of filming and editing at the time of publication of this article.

More information about the project available at: Cuba Indígena (Instagram).

Maravilloso reportage. Mi mama era de Baracoa. Yo tengo 10% de sangre indigena en mis venas. Una gran variedad indigne ethnica en mis venas. Muy orgulloso de ello.