Historians have examined ad nauseam what happened on October 10, 1868, at the Demajagua sugar mill, belonging to lawyer and landowner Carlos Manuel de Céspedes. However, they remained for a long time without information regarding what happened that day. The report written by Bartolomé Masó — Céspedes’ lieutenant —, which appeared shortly after October 10, decisively helped to clarify these facts. In said report, entitled “Report of the pronouncement made in Demajagua, in Manzanillo, on October 10, 1868, and the first meeting with the Spanish troops in Yara…,” it can be read in Masó’s own handwriting:

“Around 10 o’clock in the morning we were about five hundred patriots gathered in that sugar mill, ordered to form by the General in Chief (sic) the Cry of Independence was given! Hoisting the Standard that symbolizes it, under which they all swore the solemn oath to win or die, rather than see the soil of the Homeland trampled again by any of the tyrannies. The General in Chief gathered his slaves and declared them free as of that moment, inviting them to help us if they wanted, to conquer our freedoms; the other landowners around him did the same with theirs….”

Thanks to this document and other testimonies, it has also been possible to know that the rebels remained in Demajagua for the rest of that day and left at dawn on Sunday, October 11, for Yara, where they fought the first armed encounter with the Spanish forces. Hence, the pronouncement was called “Grito de Yara” for a long time, when in reality it should have been called “de la Demajagua.” I can imagine the pressures of that Saturday and even the arrival of the conspirators at the sugar mill the previous days, October 8 and 9. It was a scene of great hustle and bustle, of departure and arrival of emissaries to and from the other conspirators, with vertiginous actions and preparations, of discussions between the chiefs about directions and actions to follow, as well as other questions related to the political and military content of the insurrection.

The inexperienced troops that would constitute the initial detachment of the Liberation Army were organized there; and the Manifesto of the Revolutionary Junta of the Island of Cuba, our declaration of independence, was read. The banner that would guide the war actions was also shown, in addition to Céspedes’ grand symbolic gesture of granting freedom to his slaves, while inviting them to fight for Cuba. The slave master spoke to them on the night of October 9 and asked them to play the “tumba francesa” to celebrate what everyone already knew would happen the next day: the insurrection.

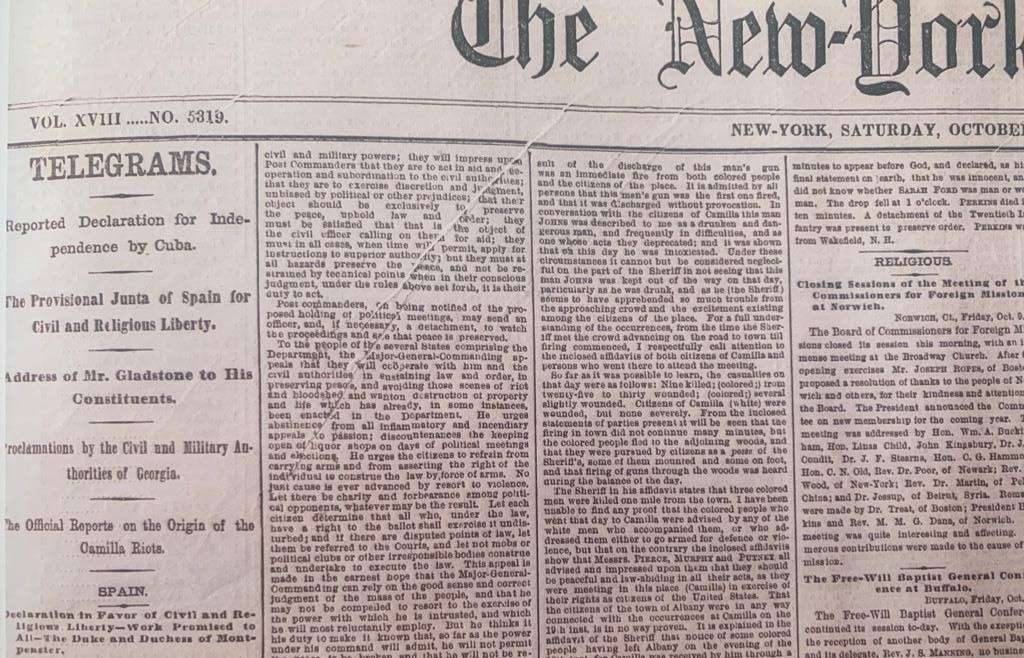

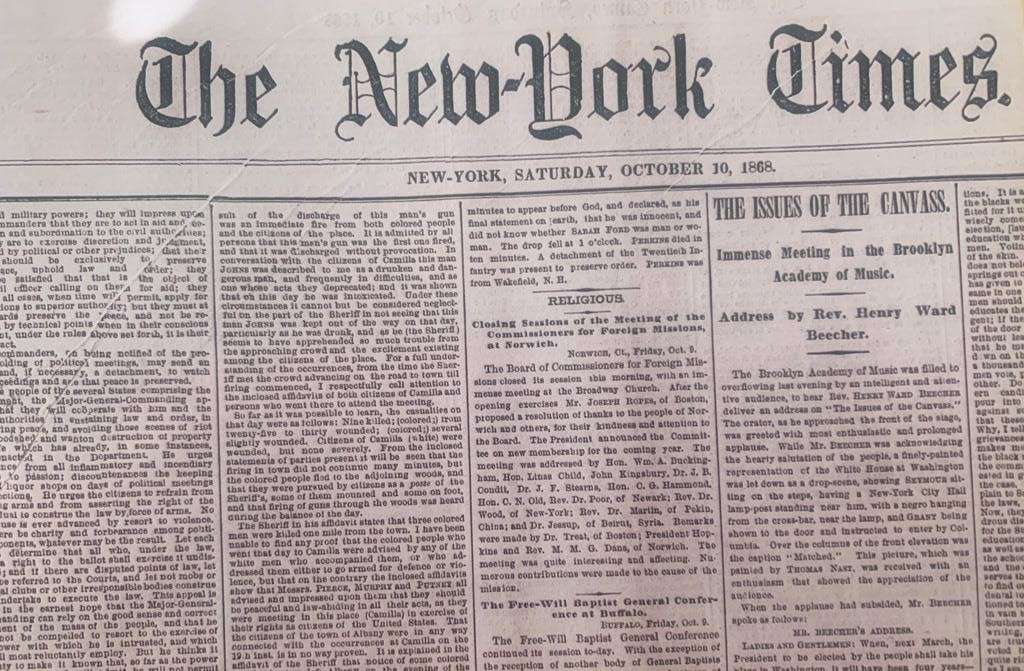

But, without a doubt, there is something that surprises in a particular way and enters an area of absolute mystery, until now. It turns out that in the edition of the U.S. newspaper The New York Times, on that Saturday, October 10, the news about the uprising that took place in Cuba appeared in the “Telegrams” section. It was published in the form of a headline, without other comments: “Reported Declaration for Independence by Cuba.” Just like that.

How could that headline be in the edition of the U.S. newspaper corresponding to the same day of the events? While the clarifying data on this does not appear, we remain in the field of speculation. One hypothesis could be related to the possible precaution taken by the conspiring patriots to send the news days before, through some representative or agent in the United States, knowing that the uprising would take place on Saturday, October 10.

Some facts help to think about this hypothesis. On the 6th of that month, the group of Manzanillo residents led by Céspedes met at Jaime Santiesteban’s El Rosario sugar mill to determine that on October 14 they would rise up in the mountains against the colonial power. Holguin, Camagüey and Santiago de Cuba residents did not agree with the date and asked for time to acquire weapons, but under pressure from Céspedes and the Las Tunas chiefs they finally accepted the decision. The date of the 14th was advanced when Céspedes received a copy of a telegram from the Spanish Captain General in which he ordered the arrest of the conspirators, himself among them. In this way, the new date of October 10 was decided, with urgency. At the meeting in El Rosario, a minute was drawn up, which was a true declaration of independence and which, compared to the Manifesto read by Céspedes on the morning of October 10, gives the idea that it could very well have been its draft.

Until today it has not been possible to know how this news reached the U.S. newspaper, what is verifiable is that The New York Times published the headline that can be seen in the previous image and that, obviously, could only appear if the scoop sent to the newspaper would have been between October 6 and 9, and not the same 10. This novel data appeared for the first time on page 46 of the book Cuba en USA, authored by Emilio Cueto and Julio Larramendi, (Polymita publishers, 2018). It was Cueto, a diligent investigator of everything concerning Cuba in the United States, who found this surprising fact. It is then that the alert arises in the face of an unexpected and totally unpublished data. Hopefully that information can encourage new searches and that one day we can have the complete package on the facts, causes and implications.

While the U.S. press published the headline on the day of the uprising, the insular Spanish press published it on October 13. According to La Gaceta Oficial, an insurrection had taken place in the eastern part of the country: “According to official telegrams from Yara, jurisdiction of Manzanillo, a party of civilians rose up on the 10th, without the ringleader who commands them being known or the object that drives it.…” As can be seen, the name of Yara and not Demajagua is the one used by the newspaper.

The rest is well known. In Yara, the patriots suffered their first defeat, in a brief confrontation that produced the first casualties — on both sides — of the war, and Céspedes ordered a withdrawal in view of the fact that the Spaniards had reached the town first and occupied advantageous defensive positions. The withdrawal went to Palmas Altas, where they met with other uprising troops and where the incipient Liberation Army was restructured; Bartolomé Masó also had a certain amount of calm there to write his report. From that point they went to Bayamo, which was occupied after three days of fierce fighting, on October 20, which allowed Céspedes to establish the capital of the insurrection for eighty-three days.

***

Note:

1 The document written and signed by Bartolomé Masó appears in the Boletín del Archivo Nacional, Havana, 1956, t LIII, pp 142-45 and t LIV, pp 151-52.