Fernando Pérez is premiering his most recent film. For consumers of Cuban films, it is news to pay attention to, since it is about our living director with a work of more sustained quality. Sensitive, controversial, committed, risky in the aesthetic proposal, with a great will to communicate, lucid, are some of the adjectives for his work. Fernando’s cinema moves and makes you think, which is the essential formula for all great art.

Now El mundo de Nelsito (2022) is the title that is coming out in search of its audience. One hundred intense minutes are enough to put on the screen the script conceived by Abel Rodríguez and the director himself, the same one that has been represented by a luxury cast in which the names of Isabel Santos, Laura de la Uz, Jacqueline Arenal, Edith Massola, Paula Ali and Mario Guerra stand out. The novel José Raúl Castro plays Nelsito, an autistic teenager who has fun imagining (disrupting?) reality.

Due to an oversight of his mother, Nelsito goes out to wander around the city, but his walk does not last long. A car hits him, and he is taken to the hospital. From his convalescent bed, he observes the nearby world, his troubled characters, and plays at rewriting, with his imaginary pen (he believes he is a writer), the possible vicissitudes of each one of them.

They are sordid stories, full of pain, that reveal a very hard day to day in Havana, an omnipresent city that is not named, where lack of affection, double standards, hatred, sexual subjugation, laziness, opportunism and other niceties reign.

As a counterpart, there is also solidarity, a generous acts and the aspiration to walk the right path, the one that could bring us closer to the end of the tunnel.

Nelsito’s neighbors, ordinary beings, who happily welcome him back home, are they the same selfish and petty characters that he imagines as the less bright side of reality?

What we suppose happens and what we believe the main character imagines propose two narrative planes that amalgamate and create a “healthy” confusion that serves as a pivot for critical thinking, the revision of the narrative material that is received through emotion but that, finally, must go through discernment. And I won’t go any further along this path so as not to mediate between the viewer and the film.

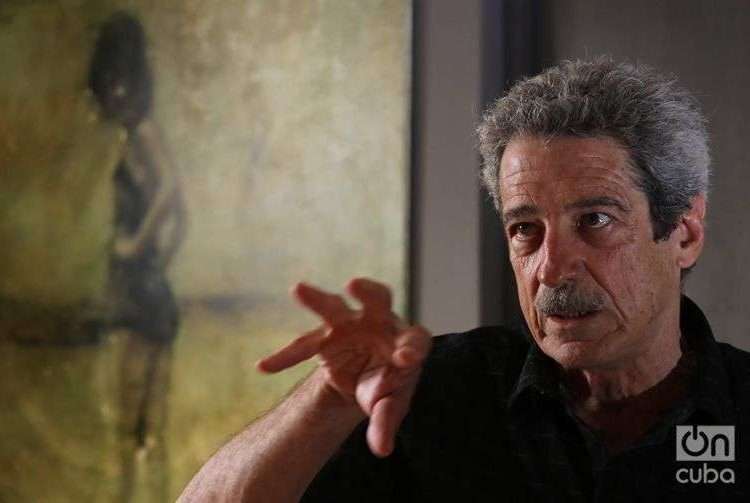

Fernando Pérez was kind enough to organize a private screening of his film for OnCuba, which was attended by other friends. The unanimous opinion of those present is that it is a firm steppingstone in the ascending career of the director, who, to my taste, put in Madagascar one of the highest levels of our filmography.

There was a debate after the screening, which could have gone on for hours, since the film gives a lot of critical material to analyze.

Here I reproduce the approach to Fernando Pérez.

Roughly speaking, I think that in your work of fiction there are two quite defined lines of work. One is made up of films with a conventional, Aristotelian narrative, such as Clandestinos (1987), Hello, Hemingway (1990), José Martí, el ojo del canario (2010), Últimos días en La Habana (2016) and Insumisas (2019). The other, frankly experimental, explores diverse narratives, with great symbolic densities. It is made up of Madagascar (1995), La vida es silbar (1998), Suite Habana (2003), Madrigal (2007), La pared de palabras (2014), and El mundo de Nelsito (2022). In both registers you have achieved notable artistic results. Does this alternation in the way of approaching the stories respond to a conscious stylistic effort or is it due to the demands of the narrative material in each case?

It responds to both principles. When I faced Clandestinos, my first feature film, it was essential to prove to myself if I knew how to tell a story or not, and I took my first step keeping in mind Aristotelian dramaturgy, dramatic curves, the genre of action cinema, where the characters are portrayed more by their actions than by their psychological depth. But, at the same time, I set out to tell a love story because, as a movie buff, I like movies that excite me and move me and make me forget that I’m watching a movie.

I walked much looser in Hello, Hemingway, but trying to show myself this second time if I could continue telling stories, not through great dramatic moments, but in a lesser, more minimalist and intimate tone, as life can be seen through the eyes of a teenager.

More than the challenge of dealing with the immediate present, Madagascar represented for me the challenge of changing register. I remember that the script, written together with Manolito Rodríguez, was built again as a classic narrative: natural locations, everyday behavior, realistic atmospheres. But in the pre-filming, those locations, behaviors and atmospheres took on a subjective plane as an expression of the protagonist’s moods and her way of seeing her surroundings.

The narration ceased to be realistic and the visual and sound framework of the film (inspired by René Magritte’s paintings) became a metaphor for the lacerations that the Special Period was leaving (more than its material precariousness) in the spirit of various generations. The metaphors, visual associations and symbols allowed, like language, to peek at and penetrate that unfathomable space of human subjectivity.

Since then, my filmography has manifested itself between these two magnetic poles as an expressive search and as a narrative requirement of each project — although, beyond the definitions and classifications, I consider that both ways must always have a dramaturgical structure that supports them.

I will continue making films that aspire to create an “impression of reality,” of something lived, and films that are the opposite, such as Madrigal, which resorts to deliberate artifice and estrangement so that, once this artificiality has been assimilated, the viewer can reach an aesthetic emotion.

They are two ways of making films that motivate me equally; although, if I had to choose, I’d go for the second.

I venture the hypothesis that the “general public” connects more easily with films like José Martí… than with films like Madagascar. Is this fact — provided you agree with me — something that particularly worries you? Do you think that excellent films such as La pared de las palabras and Suite Habana can, over time, find a more open reception, with less prejudice for the adjective “experimental”?

It is true that there is a preference for films that give an “impression of reality” and perhaps less for those that break with known narrative molds. But the reactions of what we usually call the “general public” can frequently surprise us.

I am not given to generalizations, and the public concept can be one of them, so I prefer to refer to viewers as individualities.

I remember that I once attended a screening and discussion of Suite Habana in a small movie theater in Zurich, and at the end a Chinese spectator approached me to tell me that the film had moved him because it reminded him of his childhood in Shanghai.

In that experience there were no language boundaries. The thought of Nicholas Ray (a director out of step with U.S. movies) always stays with me when he asserted that in movies there is no formula for success, but there is one for failure, and that is the idea of making everyone happy.

Unanimities are not good, neither in art nor in life. All the films I’ve made have provoked different reactions (even antagonistic ones), and that pleases me, because the diversity of criteria is what moves thought.

El mundo de Nelsito began its journey through international festivals, and this summer it will have its commercial premiere in Cuba. There has been controversy among the spectators who have managed to see it in small events and private screenings. The sides agree that the film exposes two levels of contemporary Cuban reality: what we could call real reality and the reality that Nelsito, an autistic adolescent who calls himself a writer, invents. The point under discussion is, within the discourse used, what is “real fiction” and what is “fiction-fiction.” I really liked the movie, and I think the misperception is trying to understand an unconventional story from conventional points of view. I believe that both narrative planes are sufficient and complementary, and offer the viewer a committed, complex reading full of diverse meanings. It is, as Ambrosio Fornet would say, cinema to connect. What would you contribute to the debate?

The fictional and real characters in El mundo de Nelsito could be the two sides of the same coin, because human beings are not in one piece, and life, no matter how much we want it, almost never manifests itself as a straight line.

Our behaviors are also determined by circumstances, and when these are extreme, our responses — whether passionate or rational — can rise or hit rock bottom. The lack of perfection is human: perfection belongs only to hagiography.

Nelsito is a mischievous teenager who has fun by focusing his stories on the dark side of the heart, but he also needs to rely on his alter ego (Yanelis) so that there is light next to the shadow.

I would like to invite a group of friends to see your most recent work. What do I tell them to motivate them? How to summarize in a paragraph what could be found in the dark room?

I would tell them not to pay any attention to what I have said in this interview and watch the film from their own perspective: El mundo de Nelsito will always be different depending on the look of each viewer, because it is the viewers, from their subjectivity, who complete each movie.

And an almost obligatory recommendation: that they be motivated to see it in a movie theater and never on a laptop or on the television at home.